Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Utilization Pattern of Adolescents in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Website Disclosure Subsidy.Xlsx

Subsidy Loan Details as on Ashad End 2078 S.N Branch Name Province District Address Ward No 1 Butwal SHIVA RADIO & SPARE PARTS Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-06,RUPANDEHI,TRAFFIC CHOWK 6 2 Sandhikharkaka MATA SUPADEURALI MOBILE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-06,RUPANDEHI 06 3 Butwal N G SQUARE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-11,KALIKANAGAR 11 4 Butwal ANIL KHANAL Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-5,MANIGARAM 5 5 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 6 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 7 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 8 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 9 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 10 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 11 Butwal RAMNAGAR AGRO FARM PVT.LTD Lumbini Nawalparasi SARAWAL-02, NAWALPARASI 2 12 Butwal RAMNAGAR AGRO FARM PVT.LTD Lumbini Nawalparasi SARAWAL-02, NAWALPARASI 2 13 Butwal BUDDHA BHUMI MACHHA PALAN Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHI-06,KAPILVASTU 06 14 Butwal TANDAN POULTRY BREEDING FRM PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-11,RUPANDEHI,KALIKANAGAR 11 15 Butwal COFFEE ROAST HOUSE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-09,RUPANDEHI 09 16 Butwal NUTRA AGRO INDUSTRY Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL 13 BELBAS, POUDEL PATH 13 17 Butwal SHUVA SAMBRIDDHI UNIT.AG.F PVT.LTD. Lumbini Rupandehi SAINAMAINA-1, KASHIPUR,RUPANDEHI 1 18 Butwal SHUVA SAMBRIDDHI UNIT.AG.F PVT.LTD. Lumbini Rupandehi SAINAMAINA-1, KASHIPUR,RUPANDEHI 1 19 Butwal SANGAM HATCHERY & BREEDING FARM Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-09, RUPANDEHI 9 20 Butwal SHREE LAXMI KRISHI TATHA PASUPANCHH Lumbini Palpa TANSEN-14,ARGALI 14 21 Butwal R.C.S. -

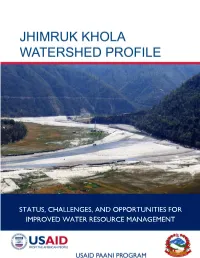

Jhimruk Khola Watershed Profile: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities for Improved Water Resource Management

STATUS, CHALLENGES, AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVED WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT I Cover photo: Jhimruk River at downstream of Jhimruk Hydro Power near Khaira. Photo credit: USAID Paani Program / Bhaskar Chaudhary II JHIMRUK KHOLA WATERSHED PROFILE: STATUS, CHALLENGES, AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVED WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Program Title: USAID Paani Program DAI Project Number: 1002810 Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Nepal IDIQ Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00014 Task Order Number: AID-367-TO-16-00001 Contractor: DAI Global LLC Date of Publication: November 23, 2018 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Contents TABLES ....................................................................................................................... VI FIGURES .................................................................................................................... VII ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 1 1. JHIMRUK WATERSHED: NATURE, WEALTH AND POWER.................. 9 2. NATURE........................................................................................................... 10 2.1 JHIMRUK WATERSHED ................................................................................................. -

S.N Local Government Bodies EN स्थानीय तहको नाम NP District

S.N Local Government Bodies_EN थानीय तहको नाम_NP District LGB_Type Province Website 1 Fungling Municipality फु ङलिङ नगरपालिका Taplejung Municipality 1 phunglingmun.gov.np 2 Aathrai Triveni Rural Municipality आठराई त्रिवेणी गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 aathraitribenimun.gov.np 3 Sidingwa Rural Municipality लिदिङ्वा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sidingbamun.gov.np 4 Faktanglung Rural Municipality फक्ताङिुङ गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 phaktanglungmun.gov.np 5 Mikhwakhola Rural Municipality लि啍वाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 mikwakholamun.gov.np 6 Meringden Rural Municipality िेररङिेन गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 meringdenmun.gov.np 7 Maiwakhola Rural Municipality िैवाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 maiwakholamun.gov.np 8 Yangworak Rural Municipality याङवरक गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 yangwarakmuntaplejung.gov.np 9 Sirijunga Rural Municipality लिरीजङ्घा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sirijanghamun.gov.np 10 Fidhim Municipality दफदिि नगरपालिका Panchthar Municipality 1 phidimmun.gov.np 11 Falelung Rural Municipality फािेिुुंग गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalelungmun.gov.np 12 Falgunanda Rural Municipality फा쥍गुनन्ि गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalgunandamun.gov.np 13 Hilihang Rural Municipality दिलििाङ गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 hilihangmun.gov.np 14 Kumyayek Rural Municipality कु म्िायक गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 kummayakmun.gov.np 15 Miklajung Rural Municipality लि啍िाजुङ गाउँपालिका -

Standard Request for Proposals: Selection of Consultants

Pyuthan Municipality Office of Municipal Executive Bijuwar,Pyuthan SELECTION OF CONSULTANTS REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS RFP No.: 02/PMO/DPR/Road /075/076 Selection of Consulting Services for: Detailed Survey and Design of Dhakhakwadi (Thadoduwa)-Barjibang-Sotre-Sari- Rolpa Urban/District Road (0+000~8+000) Office Name:Office of Pyuthan Municipality Office Address:Office of Municipal Executive , Bijuwar,Pyuthan. Financing Agency: Pyuthan Municipality Issued on: Feb,2019 0 | P a g e Pyuthan Municipality Office of the Municipal Office Bijuwar, Pyuthan INVITATION FOR SEALED BIDS/SEALED QUOTATION First Date of Publication: 2075/11/13 B.S (25th feb 2019 AD) 1. Office of the Municipal Executive, Pyuthan (OME Pyuthan) has received grant from GON and OME decide for to prepare detail Project Report of Following Projects of Pyuthan Municipality, and OME Pyuthan intends to apply the funds to cover eligible payments under the contract for Engineering consultants of details Survey, Design and Prepare report according to approved RFP and TOR. OME Pyuthan allocates fund. Bidding is open to all eligible Nepalese Consultants. 2. The OME Pyuthan invites sealed quotation from registered eligible Consultant for Preparation of Detail Project Report of Following Projects of Pyuthan Municipality 3. The Consultants having valid firm registration, VAT/PAN registration certificates, tax clearance certificate up to FY 2074/075 are eligible for bidding. 4. Interested eligible Consultants may obtain further information and inspect the bidding documents at Pyuthan Municipality -

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nepal RA Firm Renewal List from 2074-04-01 to 2075-03-21 Sno

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nepal RA Firm Renewal List From 2074-04-01 to 2075-03-21 SNo. Firm No. Name Address Phone 1 2002 D. A. & Associates Suswagat Marga, Mahankal Sthan, 01-4822252 Bouda -6,Kathmandu 2 2003 S. R. Neupane & Co. S. R. Neupane & Co., Birgunj 9845054857 3 2005 Kumar Jung & Co. Kumar Jung & Co. Hattiban, Dhapakhel- 5250079 1, Laitpur 4 2006 Ram & Co. Ram & Co. , Gaurigunj, Chitawan 5 2007 R. R. Joshi & Co. R.R. Joshi & Co. KMPC Ward No. -33, 4421020 Ga-1/319, Maitidevi, Kathmandu 6 2008 A. Kumar & Co. Tripureshowr Teku Road, Kathmandu 14260563 7 2009 Narayan & Co. Pokhara 11, Phulbari. 9846041049 8 2011 N. Bhandari & Co. N. Bhandari & Co. Maharajgunj, 9841240367 Kathmandu 9 2012 Giri & Co. Giri & Co. Dilli Bazar , Kathmandu 9851061197 10 2013 Laxman & Associates Laxman & Associates, Gaur, Rautahat 014822062, 9845032829 11 2014 Roshan & Co. Lalitpur -5, Lagankhel. 01 5534729, 9841103592 12 2016 Upreti Associates KMPC - 35, Shrinkhala Galli, Block No. 01 4154638, 9841973372 373/9, POB No. 23292, Ktm. 13 2018 K. M. S. & Associates KMPC 2 Balkhu Ktm 9851042104 14 2019 Yadav & Co. Kanchanpur-6, Saptari 0315602319 15 2020 M. G. & Co. Pokhara SMPC Ward No. 8, Pokhara 061-524068 16 2021 R.G.M. & Associates Thecho VDC Ward No. 7, Nhuchchhe 5545558 Tole, Lalitpur 17 2023 Umesh & Co. KMPC Ward No. -14, Kuleshwor, 014602450, 9841296719 Kathmandu 18 2025 Parajuli & Associates Mahankal VDC Ward No. 3, Kathmandu 014376515, 014372955 19 2028 Jagannath Satyal & Co. Bhaktapur MPC Ward No. -2, Jagate, 16614964 Bhaktapur 20 2029 R. Shrestha & Co. Lalitpur -16, Khanchhe 015541593, 9851119595 21 2030 Bishnu & Co. -

3. Local Units Codes VEC 2

3. Local units codes_VEC 2 S.N. District Local unit :yfgLo tx VEC_Code 1 Taplejung Phaktanlung Rural Municipality फ啍ता敍लु敍ग गाउँपा�लका 10101 2 Taplejung Mikwakhola Rural Municipality �म啍वाखोला गाउँपा�लका 10102 3 Taplejung Meringden Rural Municipality मे�र敍गदेन गाउँपा�लका 10103 4 Taplejung Maiwakhola Rural Municipality मैवाखोला गाउँपा�लका 10104 5 Taplejung Aatharai Tribeni Rural Municipality आठराई �त्रवेणी गाउँपा�लका 10105 6 Taplejung Phungling Municipality फुङ�ल敍ग नगरपा�लका 10106 7 Taplejung Yangwarak Rural Municipality या敍वरक गाउँपा�लका 10107 8 Taplejung Sirijanga Rural Municipality �सर�ज敍गा गाउंपा�लका 10108 9 Taplejung Sidingba Rural Municipality �स�द敍गवा गाउँपा�लका 10109 10 Sankhuwasabha Bhotkhola Rural Municipality भोटखोला गाउँपा�लका 10201 11 Sankhuwasabha Makalu Rural Municipality मकालु गाउँपा�लका 10202 12 Sankhuwasabha Silichong Rural Municipality �सल�चोङ गाउँपा�लका 10203 13 Sankhuwasabha Chichila Rural Municipality �च�चला गाउँपा�लका 10204 14 Sankhuwasabha Sabhapokhari Rural Municipality सभापोखर� गाउँपा�लका 10205 15 Sankhuwasabha Khandabari Municipality खाँदबार� नगरपा�लका 10206 16 Sankhuwasabha Panchakhapan Municipality पाँचखपन नगरपा�लका 10207 17 Sankhuwasabha Chainapur Municipality चैनपुर नगरपा�लका 10208 18 Sankhuwasabha Madi Municipality माद� नगरपा�लका 10209 19 Sankhuwasabha Dharmadevi Municipality धम셍देवी नगरपा�लका 10210 Khumbu Pasanglhamu Rural 20 Solukhumbu 10301 Municipality खु륍बु पासाङ쥍हामु गाउँपा�लका 21 Solukhumbu Mahakulung Rural Municipality माहाकुलुङ गाउँपा�लका 10302 22 Solukhumbu Sotang Rural Municipality सोताङ गाउँपा�लका -

Anthology of 108 Successful Entrepreneurs in Nepal

MICRO ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME MICRO ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Copyright Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies (MoICS), Micro Enterprise Development for Poverty Alleviation First Edition May 2018 All rights are reserved No part of this Anthology of 108 Successful Entrepreneurs in Nepal can be reproduced by any means, transmitted, translated into a machine language without the written permission of the MoICS or UNDP Nepal Published by Micro Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP) Design & print process : TheSquare Design Communication Pvt. Ltd. Jwagal, Kupondole, Lalitpur, Nepal Tel. +977 1 5260 963 / 5531 063 [email protected] www.thesquare.com.np CONTENT Monetizing entrepreneurship 13 Entrepreneurship to leadership 65 Rising from the rubble 79 Beyond economic empowerment 105 Wider Horizons 137 Taking the leap to small from micro 185 6 MICRO ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (MEDEP) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This compilation of 108 success stories contains prosperity for the whole family. Husbands of women accounts of micro-entrepreneurs supported and entrepreneurs have returned from abroad to help promoted by the Micro-Enterprise Development in their enterprises. Children are getting a good Programme (MEDEP). A majority of micro- education. The family has access to nutritious food. entrepreneurs established by MEDEP support are They have built a new house and have bought land, running their enterprises successfully. Some of them gold and in some cases vehicles. The entrepreneurs have graduated and are now capable of managing have savings in banks and cooperatives and are their businesses independently. providing employment to others like them. Their success has helped them win recognition and The stories documented in this publication have awards from the government and private sectors. -

Provincial Summary Report Province 5 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 5 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Province 5 Province Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 5 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6362-3 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance…………………………………………...........................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 5 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit…….26 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...32 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...44 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…56 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...62 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...68 Table 8. -

Source Book for Projects Financed with Foreign Assistance Fiscal Year 2021-22

(Unofficial Translation) (For Official Use Only) Source Book for Projects Financed with Foreign Assistance Fiscal Year 2021-22 . Government of Nepal Ministry of Finance 2021 www.mof.gov.np TABLE OF CONTENTS Budget Head Description Page Summary of Ministrywise Development Partners 1 Development Partnerwise Summary 3 301 Office of Prime Minister and Council of Ministers 5 305 Ministry of Finance 5 307 Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supply 6 308 Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation 6 312 Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development 10 313 Ministry of Water Supply 12 314 Ministry of Home Affairs 14 325 Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation 15 329 Ministry of Forest and Environment 15 336 Ministry of Land Management, Cooperative and Poverty Alleviation 17 337 Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport 17 340 Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizen 23 347 Ministry of Urban Development 23 350 Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 24 365 Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration 26 370 Ministry of Health and Population 28 371 Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security 31 392 National Reconstruction Authority 31 501 MOF- Financing 32 701 Province 36 801 Local Level 38 Summary of Ministrywise Development Partners Fiscal Year 2021/22 (Rs. in '00000') Foreign Grant Foreign Loan Ministry GoN Total Budget Cash Reimbursable Direct Payment Commodity Total Grant Direct Payment Reimbursable Cash Total Loan 301 Office of Prime Minister and Council of Ministers 2938 1020 1020 0 1020 -

![Xf]D Axfb'/ &Fs"/ Cfs[Lt Kgyl ऋृषिराम प](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1276/xf-d-axfb-fs-cfs-lt-kgyl-7451276.webp)

Xf]D Axfb'/ &Fs"/ Cfs[Lt Kgyl ऋृषिराम प

खुला प्रलतयोलगता配मक परीक्षाको वीकृ त नामावली वबज्ञापन नं. : २०७७/७८/३३ (लुम्륍बनी प्रदेश) तह : ३ पदः कलनष्ठ सहायक (गो쥍ड टेटर) रोल नं. उ륍मेदवारको नाम उ륍मेदवारको नाम ललंग सम्륍मललत हुन चाहेको समूह थायी म्ि쥍ला थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स बािेको नाम बाबुको नाम 1 AACHAL SINGH THAKUR आँचल l;+x &fs"/ Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Banke Sub- Metropolitan Nepalgunj eujtL l;+x &fs"/ xf]d axfb'/ &fs"/ 2 AAKRITI PANTHI cfs[lt kGyL Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Gulmi Thanapati ऋृषिराम पन्थी बाबुराम पन्थी 3 AAKRITI GIRI cfs[tL lu/L Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Rolpa Sunil Smiriti vu" lu/L zf]ef/fd lu/L 4 AARATI KHANAL cf/lt vgfn Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Tehrathum Solma lglwgfy vgfn led k|;fb vgfn 5 AARTI PARIYAR आरती पररयार Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Banke Nepalgunj भोटे ष िंह पररयार षबष्ण ु पररयार 6 AASHA BASEL cfiff a;]n Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Pyuthan Belbas VDC l/vL/fd h};L k"gf/fd h};L 7 AASHA GHIMIRE cfzf l#ld/] Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Arghakhanchi patauti lxdnfn l#ld/] sdn k|;fb l#ld/] 8 AASTHA SHRESTHA cf:yf >]i& Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Rupandehi Butwal dVvg nfn >]i& lji)f" nfn >]i& 9 AAWSAHAYAK MANI PANDEY अवशायक मषण पाण्डoे Male ख쥍ु ला Rupandehi Rohini षशतल प्र ाद पाण्डे षदनकर मषण पाण्डे 10 AAYUSHMA HAMAL K.C. -

Given Exam Symbol No. of All Institute and All Trade for Yearly and Final Exam and Back Exam Academic Year 2075/076

GIVEN EXAM SYMBOL NO. OF ALL INSTITUTE AND ALL TRADE FOR YEARLY AND FINAL EXAM AND BACK EXAM ACADEMIC YEAR 2075/076 S.N INSTITUTE NAME PROGRAMME REGULAR PAPER BACK PAPER REMARKS 1 AARATI TECHNICAL INSTITUTE, SHARADA MUNICIPALITY -02, SALYAN VJTA 101 160 47141 47180 2 Adarsha Secondary School (TECS), BIRATNAGAR COMPUTER 161 220 47181 47220 3 ALL NEPAL COLLEGE OF TECHNICAL EDUCATION, KATHMANDU VJTA 221 280 47221 47260 4 ALL NEPAL COLLEGE OF TECHNICAL EDUCATION, KATHMANDU PJTA 281 340 47261 47300 5 AMAR SECONDARY SCHOOL, BHARATPUR-22, PADAMPOKHARI PROGRAMME PJTA 341 400 47301 47340 6 AMAR SECONDARY SCHOOL, BHARATPUR-22, PADAMPOKHARI PROGRAMME VJTA 401 460 47341 47380 7 AMAR SHAHID SHREE DASHARATH CHANDA MA. VI. RAJAPUR, BARDIYA PJTA 461 520 47381 47420 8 AMAR SHAHID SHREE DASHARATH CHANDA MA. VI. RAJAPUR, BARDIYA VJTA 521 580 47421 47460 9 AMBIKA HEALTH TRAINING SCHOOL ,BHAKTAPUR LAB 581 640 47461 47500 10 AMDA InsTiTuTe of HealTh Science, JHAPA LAB 641 700 47501 47540 11 AMDA Mechi HospiTal, JHAPA LAB 701 760 47541 47580 12 Arghakhanchi Technical Training School, Arghakhanchi VJTA 761 820 47581 47620 13 ATTARIYA TECHNICAL COLLEGE, ATTARIYA, KAILALI LAB 821 880 47621 47660 14 BAGAR BABA TECHNICAL SCHOOL ,LAMAHI 5 ,DEUKHARI ,DANG LAB 881 940 47661 47700 15 BAGISWORI SECONDARY SCHOOL, CHYAMHASINGH, BKT-9 CIVIL 941 1000 47701 47740 16 BHAIRAWASHRAM SECONDARY SCHOOL, GORKHA COMPUTER 1001 1060 47741 47780 17 BIRAT HEALTH COLLEGE, MORANG LAB 1061 1120 47781 47820 18 BIRENDRANAGAR TECHNICAL INSTITUTE, SURKHET CIVIL 1121 1180 47821 47860 19 BAGALAMUKHI -

Written Examination for the Position of Management Trainee

Written Examination for the Position of Management Trainee Examination Date: 15th Baisakh 2075, Saturday Reporting Time: 8:30 AM Examination Time: 9:00 AM (Sharp) Examination Venue: Golden Gate International College, Old Baneshwor, Battisputali, Kathmandu, Nepal Instructions to shortlisted candidates: * Kindly remember your Application ID while appearing for the written examination. * You must bring original Citizenship Certificate or Driving License or Passport to appear in the written examination which will be used as identification document. * You can bring / use Calculator for written exam. SN Application ID Shortlisted Candidates Permanent Address 1 MT-435 Aagya Chand Mahendranagar, 2 MT-112 Aakriti Giri New Baneshwor, Kathmandu 3 MT-470 Abhay Kushwaha Kalaiya 4 MT-5 Abin Karki Sunsari 5 MT-489 Achyut Raj Pyakurel Tokha Muncipality -2, Kathmandu 6 MT-313 Ajay Phago Suryadoya-10, Phikkal, Ilam 7 MT-230 Ajay Pokhrel Dhurkot Bhanbhane, Nepal 8 MT-367 Ajay Yadav Janakpur 9 MT-193 Akash Kumar Sah Janakpur-10 10 MT-108 Akhilesh Yadav Bhairahawa Gallamandi 11 MT-671 Akriti Shrestha Rainas Municipality-2 Tarkughat, Lamjung 12 MT-482 Akshada Sah Nijgadh-04, Bara 13 MT-126 Aleeza Karki Tinkune, Koteshwor 14 MT-93 Alina Tandukar Babarmahal, Kathmandu 15 MT-258 Alisha Manandhar Ashok Binayak Marg, Kathmandu, Nepal 16 MT-304 Aliza Acharya Biratchowk, Koshi Haraicha, 17 MT-545 Alok Shiwakoti Sunkhani - 8 - Dolakha 18 MT-368 Ambika Dahal Nuwakot 19 MT-55 Ambika Niroula Mechi Municipality- Jhapa 20 MT-606 Amika Maharjan Imadol 21 MT-165 Amir Budhathoki