Can Malmö Learn from Freetown? Comparing the Promotion and Protection of Religious Tolerance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STUDENT HANDOUT Profiles of Young

IN HER OWN WORDS: CONFRONTING CHARLOTTESVILLE By Elissa Buxbaum, Director, Campus Affairs, ADL Sarah Kenny was Student Council president at the University of Virginia when the alt-right rallied at her school’s Charlottesville campus. She hadn’t yet returned to campus when a tiki-torch-wielding crowd of neo-Nazis and white supremacists marched through the white columns of the UVA Rotunda, spouting anti-Semitic and racist vitriol. “I had seen something on Twitter the night before, and when I woke up the next morning, mayhem had descended,” she said. “It was a surreal experience, watching TV and seeing people punching each other on the streets I was so familiar with.” Sarah spent the days that followed on the phone, trying to figure out how to respond in the aftermath, navigating the media, and thinking about what she could do to prepare students returning to campus– especially new students. She rewrote her welcome address to the first-year class. She didn’t have a playbook—she figured it out as she went along, organizing town hall meetings and fostering conversations among stakeholders. One of her biggest challenges, she said, was bringing the campus together without forcing a narrative of unity. She signed on in support of a list of action items that students of color presented to the president of the university, including removing Confederate plaques from the rotunda. In the spring, she convened a round table to update the student body. “Emotions were still very raw,” she said. Throughout the year, Sarah heard from other student leaders whose campuses were both targeted by white supremacist propaganda and inundated with peer-to-peer incidents of bias and hate. -

Erik Ullenhag, Minister for Integration Round Table Regarding Islamophobia in Stockholm

2014 Speech Stockholm 10 June 2014 Erik Ullenhag, Minister for Integration Round table regarding islamophobia in Stockholm Ladies and Gentlemen, First of all, thank you for coming to Stockholm and this round table regarding islamophobia. We need to fight islamophobia at the international level, the European level, the national level, the local level and in everyday life. And I'm very grateful that you have come all the way to Stockholm to share with us your expertise and your knowledge. Malyum Salah Hashi. She is a woman who came from the war in Mogadishu, Somalia, to the peaceful town of Tomelilla in Sweden. But it was not as peaceful as one can image. Every day when Malyum picked up her daughter from preschool she passed a school where some young students, mostly boys, shouted awful things at her. During winter time, they started to throw snow. And when the snow disappeared they started to throw stones. Some stones hit Malyum. And some stones even hit her daughter. Ladies and Gentlemen, In Europe as well as in my own country Sweden far too many individuals face threats, violence and discrimination every day. Just because of intolerance from others. Muslims in Sweden and Europe are exposed to hatred, threats, discrimination and prejudice. Mosques are attacked and vandalized and many Muslims suffer from racism in everyday life. Women with veil are subjected to verbal attacks but sometimes also physical attacks. For example some people try to tear off their veil. There is often a severely simplified and negative image that is spread about Muslims and Islam. -

Profile of Siavosh Derakhti

PROFILE OF SIAVOSH DERAKHTI Siavosh Derakhti (Sy-av-osh Der-ARK-tee) is a Swedish Muslim in his mid-twenties. At an early age, he emigrated from Iran to Sweden with his parents when his country was at war with Iraq. Siavosh first became aware of prejudice as a young boy. His two best friends were David, a Jew, and Juliano, a Roma. They bonded because they all felt as members of minority groups that they were excluded in their own country. The Muslim children in school used to bully David saying “Sieg Heil,” “Dirty Jew,” and “Jews to the gas.” Savosh became David’s bodyguard and defended him when fights would break out. Later, as a teenager, Siavosh’s father took him to Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Siavosh was deeply moved by these experiences and thought that such a trip could be the catalyst to open up a dialogue with his peers in Sweden. When he was nineteen, Siavosh founded Young Muslims Against Anti-Semitism, now known as Young People Against Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia. He says that he has taken up this cause because he sees Jews as his brothers and sisters. He works with schools and community groups to bring young Jews and Muslims together to resolve their differences. He lobbied for funding from the education department to take a group of twenty-seven students to Auschwitz. In 2013, Siavosh was awarded Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg Award for his voluntary efforts to combat xenophobia. Despite threats from fellow Muslims, Siavosh continues his work because he believes in working toward creating a safe world for everyone. -

Inledningsanförande Till Rundabordsamtal Om Islamofobi I Stockholm

2014 Tal Stockholm 10 juni 2014 Erik Ullenhag, Integrationsminister Inledningsanförande till rundabordsamtal om islamofobi i Stockholm Ladies and Gentlemen, First of all, thank you for coming to Stockholm and this round table regarding islamophobia. We need to fight islamophobia at the international level, the European level, the national level, the local level and in everyday life. And I'm very grateful that you have come all the way to Stockholm to share with us your expertise and your knowledge. Malyum Salah Hashi. She is a woman who came from the war in Mogadishu, Somalia, to the peaceful town of Tomelilla in Sweden. But it was not as peaceful as one can image. Every day when Malyum picked up her daughter from preschool she passed a school where some young students, mostly boys, shouted awful things at her. During winter time, they started to throw snow. And when the snow disappeared they started to throw stones. Some stones hit Malyum. And some stones even hit her daughter. Ladies and Gentlemen, In Europe as well as in my own country Sweden far too many individuals face threats, violence and discrimination every day. Just because of intolerance from others. Muslims in Sweden and Europe are exposed to hatred, threats, discrimination and prejudice. Mosques are attacked and vandalized and many Muslims suffer from racism in everyday life. Women with veil are subjected to verbal attacks but sometimes also physical attacks. For example some people try to tear off their veil. There is often a severely simplified and negative image that is spread about Muslims and Islam. -

Profiles of Young Activists

PROFILES OF YOUNG ACTIVISTS PROFILE OF SIAVOSH DERAKHTI Siavosh Derakhti (Sy-av-osh Der-ARK-tee) is a Swedish Muslim in his mid-twenties. At an early age, he emigrated from Iran to Sweden with his parents when his country was at war with Iraq. Siavosh first became aware of prejudice as a young boy. His two best friends were David, a Jew, and Juliano, a Roma. They bonded because they all felt as members of minority groups that they were excluded in their own country. The Muslim children in school used to bully David saying “Sieg Heil,” “Dirty Jew,” and “Jews to the gas.” Savosh became David’s bodyguard and defended him when fights would break out. Later, as a teenager, Siavosh’s father took him to Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Siavosh was deeply moved by these experiences and thought that such a trip could be the catalyst to open up a dialogue with his peers in Sweden. When he was nineteen, Siavosh founded Young Muslims Against Anti-Semitism, now known as Young People Against Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia. He says that he has taken up this cause because he sees Jews as his brothers and sisters. He works with schools and community groups to bring young Jews and Muslims together to resolve their differences. He lobbied for funding from the education department to take a group of twenty-seven students to Auschwitz. In 2013, Siavosh was awarded Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg Award for his voluntary efforts to combat xenophobia. Despite threats from fellow Muslims, Siavosh continues his work because he believes in working toward creating a safe world for everyone. -

Exhibition Timeline

Photo: Government Offices of Sweden Dahlstrand/Imagebank.sweden.se Melker Photo: LivingPhoto: History Forum IHRAPhoto: Montgomery/TT Henrik Photo: AnnaTärnhuvud/Aftonbladet/TT Photo: Ljungman/CC/Living Hanna Photo: History Forum Photo: Plinio Lepri/Scanpix Sweden Wiklund/Living Juliana Photo: History Forum Tell Ye Your Children… Tell Ye Your Children... STÉPHANE BRUCHFELD AND PAUL A. LEVINE A book about the Holocaust in Europe 1933–1945 – with new material about Sweden and the Holocaust THE LIVING HISTORY FORUM An information drive is launched to shed light on the ideology that led to The book Tell Ye Your Children … is distributed to 700 000 Swedish families The first Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust is held in January 2000. Then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan participates in two of the four Forums in Grieving Muslims by the memorial to the genocide in Srebrenica in 1995, The Living History Forum is formed – a Swedish government agency tasked On the right, seated, is Italian Archbishop Gennaro Verolino, who was the first International Holocaust Remembrance Day is commemorated each year at the Holocaust and to highlight fundamental democratic values. with school-age children. Sweden takes the initiative to establish the International Holocaust Remembrance the early 2000s. Bosnia and Herzegovina. with promoting democracy, tolerance and human rights, with the Holocaust recipient of the Per Anger Prize, established by the Swedish Government in 2004. Raoul Wallenberg Square in Stockholm and many other places in Sweden. Alliance. The Stockholm Declaration on Holocaust remembrance and combating as its starting point. He was awarded the prize for his selfless and brave efforts during the German antisemitism is adopted. -

Dervin, F. Thanks to Scandinavia?

Thanks to Scandinavia? Holocaust Education in the Nordic Countries Fred Dervin In this chapter I examine how Holocaust Education is implemented in the Nordic countries. There is often some confusion in the use of the terms Scandinavia and the Nordic countries. Geographically, historically and cultural-linguistically Scandinavia includes three countries: Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The Nordic countries are comprised of these three countries as well as Finland, Iceland and associated territories (the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Svalbard and Åland). The total population covered by the Nordic countries is approximately 30 million people. In what follows I consider the three Scandinavian countries as well as Finland. Very little is known about Holocaust Education in Iceland, who was a signatory of the 2000 Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust. The reader might find some interesting information concerning this country in the article entitled “Iceland, the Jews, and Anti-Semitism, 1625-2004”, published in 2004 by Vilhjálmur Örn Vilhjálmsson. According to Holmila and Kvist Geberts (2011: 520), interest in the Holocaust in the Scandinavian countries – and for sure in Finland too – is recent in research and education while for some of these countries public discussions around the Holocaust started straight after the War as was the case of Norway. Tellingly in his 1996 volume entitled The World Reacts to the Holocaust David Wyman did not include any single Nordic country. For Holmila and Kvist Geberts (ibid.): “This new upsurge of interest in the Holocaust more broadly reflects the dynamics and the contested nature of collective memories of wartime Scandinavia”. 1. Historical perspectives: Thanks to Scandinavia? The title of this chapter, Thanks to Scandinavia, is directly inspired by an Institution of the American Jewish Committee of the same name (http://thankstoscandinavia.org/about-us/#sthash.IBwBq9aR.dpuf). -

2012 : « L'année Raoul W Allenberg » En Suède

U niversité Sorbonne Paris IV U FR Etudes germ aniques et nordiques E tudes nordiques / Langue suédoise / Ivona V . Iacob ép. Blanc 2 0 1 2 : « l ’ a n n é e Raoul W allenberg » e n S u è d e M ém oire de M aster 2 D irigé par M onsieur le Professeur Sylvain Briens. Septem bre 2016. 1 Je dédie ce travail aux survivants de l’Holocauste d’origine hongroise qui ont participé à la Commémoration de Raoul Wallenberg en 2012 et tout particulièrement à Elie Wiesel, Prix Nobel de la Paix 1986 et à Imre Kertész, Prix Nobel de Littérature 2002. 2 Utrikesminister Carl Bildt om Wallenberg: « Ingen annan svensk har i modern tid gjorts så stora så handgripliga och så svåra insatser i humanitetens och människokärlekens tjänst som Raoul Wallenberg. Hans namn har gett ära åt Sverige. » « Men den Budapests befrielse han hoppats på blev inte befrielse. En terror avlöste en annan. En människofientlig ideologi trädde in på den scen en annan tvingats lämna. » « Wallenberg kämpade mot den ena av sin tids terrordiktaturen och föll offer för en annan.. » Traduction du suédois en français : Citation de Carl Bildt, Ministre suédois des Affaires étrangères à propos de Raoul Wallenberg : « Aucun autre Suédois des temps modernes n’a pas fait des efforts si grands et si tangibles pour l’action humanitaire et par l’amour des êtres humains que Raoul Wallenberg. Son nom fait honneur de la Suède . » « Mais la libération de Budapest qu’il espérait ne fut pas une rédemption. Une terreur a suivi une autre. -

Profiles of Young Activists

PROFILES OF YOUNG ACTIVISTS PROFILE OF SIAVOSH DERAKHTI Siavosh Derakhti (Sy-av-osh Der-ARK-tee) is a Swedish Muslim in his mid-twenties. At an early age, he emigrated from Iran to Sweden with his parents when his country was at war with Iraq. Siavosh first became aware of prejudice as a young boy. His two best friends were David, a Jew, and Juliano, a Roma. They bonded because they all felt as members of minority groups that they were excluded in their own country. The Muslim children in school used to bully David saying “Sieg Heil,” “Dirty Jew,” and “Jews to the gas.” Savosh became David’s bodyguard and defended him when fights would break out. Later, as a teenager, Siavosh’s father took him to Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Siavosh was deeply moved by these experiences and thought that such a trip could be the catalyst to open up a dialogue with his peers in Sweden. When he was nineteen, Siavosh founded Young Muslims Against Anti-Semitism, now known as Young People Against Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia. He says that he has taken up this cause because he sees Jews as his brothers and sisters. He works with schools and community groups to bring young Jews and Muslims together to resolve their differences. He lobbied for funding from the education department to take a group of twenty-seven students to Auschwitz. In 2013, Siavosh was awarded Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg Award for his voluntary efforts to combat xenophobia. Despite threats from fellow Muslims, Siavosh continues his work because he believes in working toward creating a safe world for everyone. -

Swedish Muslims and Secular Society: Faith- Based Engagement and Place

Swedish Muslims and Secular Society: Faith- Based Engagement and Place Ingemar Elander, Charlotte Fridolfsson and Eva Gustavsson Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. This is an electronic version of an article published in: Ingemar Elander, Charlotte Fridolfsson and Eva Gustavsson, Swedish Muslims and Secular Society: Faith-Based Engagement and Place, 2015, Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, (26), 2, 145-163. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations is available online at informaworldTM: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2015.1013324 Copyright: Taylor & Francis (Routledge): SSH Titles http://www.routledge.com/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-117363 [vrh]I. Elander, C Fridolfsson and E. Gustavsson[/vrh] [rrh]Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations[/rrh] [fn]Corresponding author: Email: [email protected][/fn] Swedish Muslims and Secular Society: Faith-based Engagement and Place Ingemar Elandera, Charlotte Fridolfssonb and Eva Gustavssona aÖrebro University, Örebro, Sweden; bLinköping University, Linköping, Sweden This article sets out to explore how Muslims in Sweden identify with and create social life in the place where they live, i.e. in their neighbourhood, in their town/city and in Swedish society at large. In a paradoxical religious landscape that includes a strong Lutheran state church heritage and a Christian free-church tradition, in what is, nevertheless, a very secular society, Muslims may choose different strategies to express their faith, here roughly described as “retreatist,” “engaged” or “essentialist/antagonistic”. Focusing on a non-antagonistic, engaged stance, and drawing upon a combination of authors’ interviews, and materials published in newspapers and on the internet, we first bring to the fore arguments by Muslim leaders in favour of creating a Muslim identity with a Swedish brand, and second give some examples of local Muslim individuals, acting as everyday makers in their neighbourhood, town or city. -

2018 Highlights

THE GLOBAL ADDRESS FOR MUSLIM-JEWISH RELATIONS 2018 HIGHLIGHTS Rabbi Marc Schneier Dear Friends, President Chris Sacarabany We have the pleasure to share FFEU’s 2018 Highlights Executive Director Brochure which showcases the important contributions Marie Banzon-Prince the Foundation has made during the past year: Executive Assistant FFEU has deepened its connections with political and Samia Hathroubi European Coordinator religious leaders from the Gulf Region. Rabbi Marc Schneier has worked to build Jewish life in the Gulf. Under his leadership, FFEU brought a delegation from BOARD OF TRUSTEES the Hampton Synagogue to Bahrain, the first-ever Jewish congregational mission to an Arabian Gulf state. Rabbi Ken Sunshine Secretary Schneier was later appointed as special advisor to the King Hamad Global Center for Peaceful Coexistence by Michael Heningburg Jr. Treasurer H.M. King Hamad and the Bahraini Court. Qatar tapped Rabbi Schneier to facilitate kosher food and other Jason Kampf Trustee amenities to accommodate the Jewish guests who will be visiting the World Cup 2022. Over the last year, Rabbi Joseph Koren Schneier worked with the United Arab Emirates leadership Trustee to help grow its Jewish community. Ali Naqvi Trustee FFEU launched its benchmark poll on Muslim-Jewish David Renzer relations, which found that gaps between Muslim and Trustee Jewish communities in the United States are much smaller than previously thought. 1 East 93rd Street, Suite 1C New York, New York 10128 In this spirit, we are most grateful to all of our friends, longtime and new partners based in 25 countries who Tel: 917.492.2538 took part in the 10th anniversary of FFEU’s International Fax: 917.492.2560 Season of Twinning. -

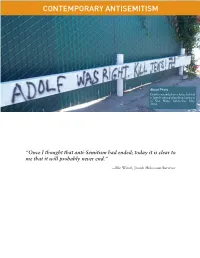

Contemporary Antisemitism

CONTEMPORARY ANTISEMITISM About Photo Graffiti scrawled on a fence behind a Jewish-owned plumbing business in Van Nuys, California, May 2014. “Once I thought that anti-Semitism had ended; today it is clear to me that it will probably never end.” —Elie Wiesel, Jewish Holocaust Survivor Preparing to Use This Lesson Below is information to keep in mind when using this lesson. In some cases, the points elaborate on general suggestions listed in the “Teaching about the Holocaust” section in the Introduction of the Echoes and Reflections Teacher’s Resource Guide, and are specific to the content of the lesson. This material is intended to help teachers consider the complexities of teaching the Holocaust and its aftermath and to deliver accurate and sensitive instruction. y When teaching about the Holocaust, it is essential to introduce students to the concept of antisemitism. The Teacher’s Resource Guide explores this topic in “Lesson Two: Antisemitism,” which provides important context to understanding how the Holocaust could happen and delves into related concepts of propaganda, stereotypes, and scapegoating. y Because antisemitism did not end after the Holocaust, teachers can help make this history relevant and meaningful to students’ own lives by connecting past events to the present through the exploration of antisemitism today. It is recommended that teachers introduce students to contemporary expressions of antisemitism after they have an understanding of the traditional forms of antisemitism that have existed for centuries. y Introducing students to contemporary antisemitism will likely expose them to new and unique themes, including the demonization of Israel and its leaders.