Hallyu Across the Desert: K-Pop Fandom in Israel and Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

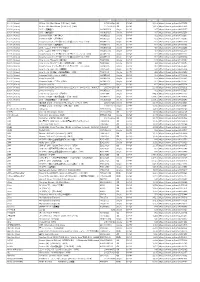

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Class of 2020

QIMAM FELLOWSHIP Empowering High-Potential University Students in Saudi Arabia CLASS OF 2020 Founding Partner Table of Contents Message from our Founding Partner ......................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 Corporate Partners ...................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Partners .................................................................................................................... 14 Program Gallery ........................................................................................................................ 22 Class of 2020 .............................................................................................................................26 Team ..........................................................................................................................................52 PAGEPAGE 1 1 Message from our Founding Partner When much of the Middle East region went into lockdown in March of 2020, there was a lot of uncertainty about whether or not we’d be able to continue the Qimam Fellowship journey against the backdrop of the Coronavirus Pandemic. We have been nothing short of amazed by the response of our partners and our participants to make it happen. And we were inspired by the commitment of young leaders in Saudi Arabia -

Glossary Ahengu Shkodran Urban Genre/Repertoire from Shkodër

GLOSSARY Ahengu shkodran Urban genre/repertoire from Shkodër, Albania Aksak ‘Limping’ asymmetrical rhythm (in Ottoman theory, specifically 2+2+2+3) Amanedes Greek-language ‘oriental’ urban genre/repertory Arabesk Turkish vocal genre with Arabic influences Ashiki songs Albanian songs of Ottoman provenance Baïdouska Dance and dance song from Thrace Čalgiya Urban ensemble/repertory from the eastern Balkans, especially Macedonia Cântarea României Romanian National Song Festival: ‘Singing for Romania’ Chalga Bulgarian ethno-pop genre Çifteli Plucked two-string instrument from Albania and Kosovo Čoček Dance and musical genre associated espe- cially with Balkan Roma Copla Sephardic popular song similar to, but not identical with, the Spanish genre of the same name Daouli Large double-headed drum Doina Romanian traditional genre, highly orna- mented and in free rhythm Dromos Greek term for mode/makam (literally, ‘road’) Duge pjesme ‘Long songs’ associated especially with South Slav traditional music Dvojka Serbian neo-folk genre Dvojnica Double flute found in the Balkans Echos A mode within the 8-mode system of Byzan- tine music theory Entekhno laïko tragoudhi Popular art song developed in Greece in the 1960s, combining popular musical idioms and sophisticated poetry Fanfara Brass ensemble from the Balkans Fasil Suite in Ottoman classical music Floyera Traditional shepherd’s flute Gaida Bagpipes from the Balkan region 670 glossary Ganga Type of traditional singing from the Dinaric Alps Gazel Traditional vocal genre from Turkey Gusle One-string, -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

September 2018

KSAA Newsletter #3 Sept 2018 September 2018 Issue 3 1 | Page KSAA Newsletter #3 Sept 2018 Korean Studies Association of Australasia Executive Committee President Treasure Assoc. Prof. Jo Elfving-Hwang Assoc. Prof. Roald Maliangkay University of Western Australia (UWA), Australian National University (ANU), Perth, Australia Canberra, Australia Vice President Secretary Assoc. Prof. Bronwen Dalton Dr Andy Jackson University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), Monash University, Melbourne, Australia Australia Website Manager Newsletter Editor Dr Andrew Jackson Dr Sunhee Koo University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Regular Members Dr Seong-Chul Shin University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Dr Jane Park University of Sydney, Australia 2 | Page KSAA Newsletter #3 Sept 2018 Table of Contents The President’s Word 4 Photos from the 2017 KSAA Conference 5 University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 6 University of Technology, Sydney 7 Macquarie University, Sydney 7 University of Western Australia, Perth 8 Monash University, Melbourne 12 University of Canterbury, Christ Church, NZ 15 University of Auckland, Auckland 15 Announcement 19 2017 KSAA Conference Report by Browen Dalton 21 The KSAA Newsletter is edited by Dr Sunhee Koo. Cover image: “P’ungmul Nori,” the first prize winner of the 46th Korea Tourism Photo Contest (from “Korea.Net” http://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Travel/view?articleId=163142 accessed on 11 September 2018). The prize-winning works can be viewed at the Korea Tourism Organization (KTO) website (http://enugallery.visitkorea.or.kr). Copyright of KSAA Newsletter (and all its content) is held by the Korean Studies Association of Australasia (KSAA). Homepage: https://koreanstudiesaa.wordpress.com/ 3 | Page KSAA Newsletter #3 Sept 2018 The President’s Word Dear members, Welcome to our new edition of the KSAA Newsletter! Firstly as the new President, on behalf of the new Executive Committee I would like to thank the previous committee members Dr Changzoo Song and Duk-soo Park for their work for KSAA. -

Playing with the Dustbin of History | Norient.Com 28 Sep 2021 22:51:13

Playing with the Dustbin of History | norient.com 28 Sep 2021 22:51:13 Playing with the Dustbin of History REVIEW by Thomas Burkhalter The Lebanese-Swiss duo Praed experiments with sounds that cultural elites call trash or kitsch. Through Praed’s style, they attack cultural canons within the Arab World, and they present a fresh mix towards Europe. Here is a different take on Exotica. From the Norient book Seismographic Sounds (see and order here). Praed, the duo of Lebanese Raed Yassin and Swiss Paed Conca, perform popular media sounds from the Arab world with techniques from experimental music. On their first CD The Muesli Man (2009), we hear lots of samples: gunshots, someone screaming, music from Egyptian films, a speech by iconic president Gamal Abdel Nasser, Arabic pop music from the 1980s, electric bass, virtuoso clarinet playing, electronica sounds – all held together through a wide range of editing and manipulation techniques. On their second release Made in Japan (2011), Yassin sings over a sample of Egyptian pop-star Mahmoud El Husseini while a bathroom-pipe is bursting. Japanese voices, screaming, and dub-grooves are interlaced. All of that is put into a grinder and mixed with prepared double- and E-bass, varying playing techniques on the clarinet and scratches from record players and tape recorders. The approach is discussed openly by the duo’s label Annihaya, https://norient.com/stories/dustbin-of-history Page 1 of 6 Playing with the Dustbin of History | norient.com 28 Sep 2021 22:51:13 which specializes in the «displacement, deconstruction and ‹recycling› of popular or folkloric musical cultures», as described in the «about» section. -

Women in Sha'bi Music: Globalization, Mass Media and Popular Music in the Arab World

WOMEN IN SHA'BI MUSIC: GLOBALIZATION, MASS MEDIA AND POPULAR MUSIC IN THE ARAB WORLD DANA F. ACEE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC December 2011 Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Dana F. Acee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis focuses on sha’bi music, a style of popular music in the Arab world. More specifically, it discusses the role of women in sha’bi music, focusing on singers Nancy Ajram and Haifa Wehbe as examples of female pop singers. I take a feminist approach to understanding the lives, images, and legacies of two of the most influential female singers of the twentieth century, Umm Kulthum and Fairouz, and then I explore how these legacies have impacted the careers and societal expectations of Ajram and Wehbe. Several issues are explicated in the thesis, including the historic progression of popular music, the impacts of globalization and westernization, and the status of women as performers in the Arab world. The fan bases of the various female sha’bi singers are explored to examine why people are drawn to popular music, how youth cultures utilize music to define their generations, and why some people in the Arab world have problems with this music and/or with the singers: their lyrics, clothing, dancing bodies, and music videos. My ethnography on these issues among Arabs in Bowling Green, Ohio, reveals how members of the diaspora address the tensions of this music and the images of female performers. -

THE GLOBALIZATION of K-POP by Gyu Tag

DE-NATIONALIZATION AND RE-NATIONALIZATION OF CULTURE: THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP by Gyu Tag Lee A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA De-Nationalization and Re-Nationalization of Culture: The Globalization of K-Pop A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Gyu Tag Lee Master of Arts Seoul National University, 2007 Director: Paul Smith, Professor Department of Cultural Studies Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2013 Gyu Tag Lee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wife, Eunjoo Lee, my little daughter, Hemin Lee, and my parents, Sung-Sook Choi and Jong-Yeol Lee, who have always been supported me with all their hearts. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation cannot be written without a number of people who helped me at the right moment when I needed them. Professors, friends, colleagues, and family all supported me and believed me doing this project. Without them, this dissertation is hardly can be done. Above all, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their help throughout this process. I owe my deepest gratitude to Dr. Paul Smith. Despite all my immaturity, he has been an excellent director since my first year of the Cultural Studies program.