Claremont Trio Misha Amory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Viola Society Newsletter No. 17, November 1979

AMERICAN VIOLA SOCIETY (formerly Viola Research Society) American Chapter of the INTERNATIONALE VIOLA FORSCI.IUNGSGESELLSCIIAFT ------------ __-,l-_lll_--II_ ..s-- November NEWSLETTER 17 1979 ----- - -- ----I- "YOU'VE COME A LONG WAY, BABY! " A REPCRT ON TH3 SEVZKTE INTERXATIC'NAL VIOLA CONGRESS PROTJO, UTAH The Seventh International Viola Congress, which took place July 12, 13, and 14 on the canipus of Eriehan; Young University, was a very epecial event on several counts. Sponsored by the American Viola Society and Brieham Youne University, the congress was held in t.he Frenklln S, Harris Fine Arts Center--& superb ccmplex that offered first-class concert halls, lecture roous, and exhibition galleries. Two celebrations, important to violists, took place durine the congress. The first was an anticipatory musics1 and biographical celebration of the 100th birthday of Ernest Bloch (born 1880), manifested by performances of all his worke for viola and a talk on his life and music by Suzanne Bloch, his dsuehter. The second was the 75th birthday of William Primrose. The viclists heard during the three days represented a stunning and consi~tentlyhigh level of performance--so~ethM that has become more and more the norm for viola playing today and synonymous with American strine playing in eeneral. Dr. David Dalton, the hoet chairperson of the congress and a mezber of BYU's ffiusic faculty, did an outstanding Job of oreanizinfr and oversaeing the congress, aided by the university 'a Music Department faculty and staff. No large meetine can be without flaws, but this caneress was one of the smocthest and least-blemished ever witnessed by this writer. -

Music at the Gardner Fall 2019

ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM NON-PROFIT ORG. 25 EVANS WAY BOSTON MA 02115 U.S. POSTAGE PAID GARDNERMUSEUM.ORG PERMIT NO. 1 BOSTON MA JOHN SINGER SARGENT, EL JALEO (DETAIL), 1882 MUSIC AT THE GARDNER FALL 2019 COVER: PHOENIX ORCHESTRA FALL the Gardner at Music 2019 MEMBER CONCERT MUSIC AT THE GARDNER TICKET PRESALE: FALL 2019 JULY 24 – AUGUST 5 WEEKEND CONCERT SERIES / pg 2 The Gardner Museum’s signature series HELGA DAVIS GEORGE STEEL DANCE / pg 15 South Korean dance duo All Ready, 2019 Choreographers-in-Residence, FROM THE CURATOR OF MUSIC dazzles with a series of performances, including a world premiere The Gardner Museum is today much as it was in Isabella’s time — at once a collection of her treasures from around the world and a vibrant place where artists find inspiration and push forward in new creative directions. AT-A-GLANCE / pg 16 TICKET INFORMATION / inside back cover This fall’s programming embodies that spirit of inspiration and creative vitality. It’s a season of firsts — including the Calderwood Hall debut by Randall Goosby, a rising international star of the violin, and premieres of works by lesser-known composers Florence Price and José White Lafitte never before performed in Boston. 25 YEARS OF ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE This season also finds meaning through Isabella’s collection. Claremont Performances celebrating the Museum’s fall special Trio will help celebrate 25 years of our Artists-in-Residence program exhibition, which highlights our 25-year history with a selection of works distinctly connected to Isabella, and South of fostering relationships with contemporary artists Korean duo All Ready — 2019 Choreographers-in-Residence — will Monday, October 14, 10 am – 4 pm perform new works created especially for the Museum. -

ONGAKU RECORDS RELEASES “Jonathan Cohler & Claremont Trio”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For More Information: http://ongaku-records.com/PR20090115.pdf Web http://ongaku-records.com/ Email [email protected] Phone 781-863-6108 • Fax 781-863-6105 ONGAKU RECORDS RELEASES “Jonathan Cohler & Claremont Trio” CD BOSTON January 15, 2009 — Ongaku Records announced the release of Jonathan Cohler & Claremont Trio (024-122), a CD featuring world renowned clarinetist Jonathan Cohler and the acclaimed Claremont Trio. The new release includes Beethoven Trio in B-flat Major, Op. 11, Brahms Trio in A Minor, Op. 114, and the rarely recorded Dohnányi Sextet in C Major, Op. 37. Cohler and the Claremonts are joined by Boston Symphony Orchestra principal hornist James Sommerville and Borromeo Quartet violist Mai Motobuchi in the Dohnányi. The recordings of the Beethoven and Brahms have already been acclaimed by Fanfare Magazine as the best of the best. “...the recording is ideal...and the playing is uniformly lovely... I know of no finer recording of the Beethoven, and this one stands with the best classic versions of the Brahms.” The CD features the award-winning engineering of Brad Michel, and it was recorded in the beautiful acoustics of the Rogers Center for the Arts at Merrimack College in North Andover, Massachusetts. Accompanying the CD is an in-depth 20-page booklet that gives a full and detailed explanation of the history behind these works. These detailed historical notes have become a hallmark of Ongaku Records releases that sets them apart from other recordings. This recording was produced using the latest in 24-bit digital recording technology, and was edited and mastered throughout in 24-bits to preserve the pristine audiophile quality sound for which Ongaku Records has become known. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For More Information: http://ongaku-records.com/PR20140801.pdf Web http://ongaku-records.com/ Email [email protected] Fax 781-863-6105 ONGAKU RECORDS RELEASES “AMERICAN TRIBUTE” CD FEATURING CLARINETIST JONATHAN COHLER AND PIANIST RASA VITKAUSKAITE Boston, MA — Ongaku Records, Inc. released American Tribute (024-125), the third CD of today’s leading clarinet-piano duo, Jonathan Cohler and Rasa Vitkauskaite. The CD is dedicated to the memory of those who died at the Boston Marathon bombing on April 15, 2013, and in support of those who were injured on that terrible day. As the duo explains in the extensive and scholarly program notes, “Our real power emanates from our ideas and our freedom … As Bernstein said so eloquently, ‘This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.’” American Tribute features the following repertoire: ● Leonard Bernstein Sonata ● Victor Babin Hillandale Waltzes ● Robert Muczynski Time Pieces, Op. 43 ● Simon Sargon KlezMuzik ● Dana Wilson Liquid Ebony ● Paquito D’Rivera Invitación al Danzón, Val Venezolano, Contradanza Referring to the composers, Cohler and Vitkauskaite write, “Each driven by their own inner and outer forces have become uniquely part of the American Dream.” American Tribute features almost 70 years of musical life in the United States. Across this span of time, one can see an incredible variety of styles, traditions, schools, backgrounds, and musical experiences. The music represents the essence of America and what makes America the real melting pot. American Tribute takes us on six journeys of success, acclaim, musical inspiration and freedom. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Onathan Cohler Is Recognized Throughout the World As “An Absolute Master of the Clarinet” (In- J Ternational Clarinet Association’S Clarinet Maga- Zine)

onathan Cohler is recognized throughout the world as “an absolute master of the clarinet” (In- J ternational Clarinet Association’s Clarinet Maga- zine). Through his performances around the world and on record, he has thrilled an ever-widening audience with his incredible musicianship and total technical command. His technical feats have been hailed as “su- perhuman” and Fanfare Magazine has placed him in the pantheon of legendary musicians: “one thinks of Dinu Lipatti.” In recent years, Mr. Cohler has teamed up with multiple award-winning Lithuanian pianist Rasa Vit- kauskaite to form today's leading clarinet-piano duo, which is featured in three recent recordings: American Tribute, Romanza, and Rhapsodie Française. This sea- son he will release the second in a series of recordings in which he is featured as soloist, conductor, and music editor: Cohler plays and Conducts Mozart with the Anima Musicae Chamber Orchestra of Budapest. This follows last season’s highly acclaimed release of Cohler plays and conducts Weber with the world-renowned Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra of Budapest. A highly acclaimed recording artist, his recordings have received numerous accolades and awards including nomi- nation for the INDIE Award, the Outstanding Recording mark of the American Record Guide, BBC Music Magazine’s Best CDs of The Year selection, and top ratings from magazines, radio stations, and record guides worldwide including Penguin Guide, BBC Music Magazine, MusicWeb International, and Listener Magazine, which wrote, “Cohler pos- sesses such -

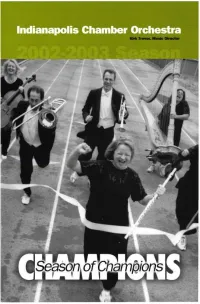

Iseason of Cham/Dions

Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra Kirk Trevor, Music Director ISeason of Cham/Dions <s a sizzling performance San Francisco Examiner October 14, 2002 February 23, 2003 7:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Ilya Kaler, violin Gabriela Demeterova, violin November 4, 2002 March 24, 2003 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. Paul Barnes, piano Larry Shapiro, violin Marjorie Lange Hanna, cello Csaba Erdelyi, viola December 15, 2002 April 13, 2003 2:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Bach's Christmas Handel's Messiah Oratorio with with Indianapolis Indianapolis Symphonic Choir Symphonic Choir and Eric Stark January 27, 2003 May 12, 2003 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. Christopher Layer, Olga Kern, piano bagpipes simply breath-taking Howard Aibel. New York Concert Review All eight concerts will be performed at Clowes Memorial Hall of Butler University. Tickets are $20 and available at the Clowes Hall box office, Ticket CHAMBER Central and all Ticketmaster ticket ORCHESTRA centers or charge by phone at Kirk Trevor, Music Director 317.239.1000. www.icomusic.org Special Thanks CG>, r:/ /GENERA) L HOTELS CORPORATION For providing hotel accommodations for Maestro Trevor and the ICO guest artists Wiu 103.7> 951k \%ljm 100.7> 2002-2003 Season Media Partner With the support of the ARTSKElNDIANA % d ARTS COUNCIt OF INDIANAPOLIS * ^^[>4foyJ and Cily o( Indianapolis INDIANA ARTS COMMISSJON l<IHWI|>l|l»IMIIW •!••. For their continued support of the arts Shopping for that hard-to-buy-for friend relative spouse co-worker? Try an ICO 3-pak Specially wrapped holiday 3-paks are available! Visit the table in the lobby tonight or call the ICO office at 317.940.9607 The music performed in the lobby at tonight's performance was provided by students from Lawrence Central High School Thank you for sharing your musical talent with us! Complete this survey for a chance to win 2 tickets to the 2003-2004 Clowes Performing Arts Series. -

MOZART Piano Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 Clarinet Quintet

111238 bk Szell-Goodman EU 11/10/06 1:50 PM Page 5 MOZART: Quartet No. 1 in G minor for Piano and Strings, K. 478 20:38 1 Allegro 7:27 2 Andante 6:37 MOZART 3 Rondo [Allegro] 6:34 Recorded 18th August, 1946 in Hollywood Matrix nos.: XCO 36780 through 36785. Piano Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 First issued on Columbia 72624-D through 72626-D in album M-773 MOZART: Quartet No. 2 in E flat major for Piano and Strings, K. 493 21:58 Clarinet Quintet 4 Allegro 7:17 AN • G 5 Larghetto 6:44 DM EO 6 O R Allegro 7:57 Also available O G Recorded 20th August, 1946 in Hollywood G E Matrix nos.: XCO 36786 through 36791. Y S Z First issued on Columbia 71930-D through 71932-D in album M-669 N E N L George Szell, Piano E L Members of the Budapest String Quartet B (Joseph Roisman, Violin; Boris Kroyt, Viola; Mischa Schneider, Cello) MOZART: Quintet in A major for Clarinet and Strings, K. 581 27:20 7 Allegro 6:09 8 Larghetto 5:42 9 Menuetto 6:29 0 Allegretto con variazioni 9:00 Recorded 25th April, 1938 in New York City Matrix nos.: BS 022904-2, 022905-2, 022902-2, 022903-1, 022906-1, 022907-1 1 93 gs and CS 022908-2 and 022909-1. 8-1 rdin First issued on Victor 1884 through 1886 and 14921 in album M-452 946 Reco 8.110306 8.110307 Benny Goodman, Clarinet Budapest String Quartet (Joseph Roisman, Violin I; Alexander Schneider, Violin II, Boris Kroyt, Viola; Mischa Schneider, Cello) Budapest String Quartet Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn Joseph Roisman • Alexander Schneider, Violins Boris Kroyt, Viola Mischa Schneider, Cello 8.111238 5 8.111238 6 111238 bk Szell-Goodman EU 11/10/06 1:50 PM Page 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791): become more apparent than its failings. -

FORTISSIMO Nº 8 — 2015 OUTUBRO 58 Ministério Da Cultura E Governo De Minas Gerais Apresentam

FORTISSIMO Nº 8 — 2015 OUTUBRO 58 Ministério da Cultura e Governo de Minas Gerais APRESENTAM SUMÁRIO p. 8 Fabio Mechetti, regente ALLEGRO VIVACE Benedetto Lupo, piano Quinta Sexta 01/10 02/10 RAVEL Menuet Antique SCRIABIN Concerto para piano em fá sustenido menor, op. 20 TCHAIKOVSKY Sinfonia nº 6 em si menor, op. 74, “Patética” p. 20 Christoph König, regente convidado PRESTO VELOCE Alexandre Barros, oboé Quinta Sexta Marcus Julius Lander, clarinete Catherine Carignan, fagote 08/10 09/10 Alma Maria Liebrecht, trompa MOZART Sinfonia concertante em Mi bemol maior, K. 297b BRUCKNER Sinfonia nº 6 em Lá maior p. 38 Fabio Mechetti, regente ALLEGRO VIVACE Baiba Skride, violino Quinta Sexta 15/10 16/10 SIBELIUS Suíte Karelia, op. 11 NIELSEN Concerto para violino, op.33 GRIEG Suíte Lírica, op. 54 GRIEG Danças norueguesas, op. 35 8 9 FABIO MECHETTI, regente BENEDETTO LUPO, piano ALLEGRO Quinta 01/10 PROGRAMA VIVACE Sexta 02/10 Maurice RAVEL Menuet Antique Alexander SCRIABIN Concerto para piano em fá sustenido menor, op. 20 BENEDETTO • Allegro LUPO, • Andante piano • Allegro moderato – INTERVALO – Piotr Ilitch TCHAIKOVSKY Sinfonia nº 6 em si menor, op. 74, “Patética” • Adagio – Allegro non troppo • Allegro con grazia PATROCÍNIO • Allegro molto vivace • Finale: Adagio lamentoso 3 CAROS AMIGOS E AMIGAS, Divulgamos hoje a programação com sua Suíte Karelia. Recebemos da Temporada 2016 da Nossa! mais uma vez o grande pianista Filarmônica. Como sempre, italiano Benedetto Lupo, assim teremos uma grande diversidade de como apresentamos ao nosso público repertório, solistas internacionais a jovem violinista Baiba Skride da maior qualidade, comemorações e o regente Christoph König. -

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL 1992-1996 June 4-28, 1992

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL 1992-1996 LOCATION: ROCKPORT ART ASSOCIATION 1992 June 4-28, 1992 Lila Deis, artistic director Thursday, June 4, 1992 GALA OPENING NIGHT CONCERT & CHAMPAGNE RECEPTION New Jersey Chamber Music Society Manhattan String Quartet Trio in C major for flute, violin and cello, Hob. IV: 1 Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Suite No. 6 in D major, BWV 1012 (arr. Benjamin Verdery) Johann Sebastian Bach, (1685-1750) Trio for flute, cello and piano Ned Rorem (1923-) String Quartet in D minor, D. 810 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Friday, June 5, 1992 MUSIC OF THE 90’S Manhattan String Quartet New Jersey Chamber Music Society Towns and Cities for flute and guitar (1991) Benjamin Verdery (1955-) String Quartet in D major, Op. 76, No. 5 Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Quartet in E-flat major for piano and strings, Op. 87 Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Saturday, June 6, 1992 New Jersey Chamber Music Society Manhattan String Quartet Sonata in F minor for viola and piano, Op. 120, No. 1 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) String Quartet No. 4 Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Trio in E-flat major for piano and strings, Op. 100, D.929 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Sunday, June 7, 1992 SPANISH FIESTA Manhattan String Quartet New Jersey Chamber Music Society With Lila Deis, soprano La Oración del Torero Joaquin Turina (1882-1949) Serenata for flute and guitar Joaquin Rodrigo (1902-) Torre Bermeja Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) Cordóba (arr. John Williams) Albeniz Siete Canciones Populares Españolas Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) Navarra for two violins and piano, Op. -

For Immediate Release

For Immediate Release THE GUARNERI STRING QUARTET WILL CELEBRATE ITS 40TH ANNIVERSARY BY GIVING A GIFT TO THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK CITY – A SERIES OF EVENTS AT LINCOLN CENTER, MONDAY AND TUESDAY, APRIL 11 AND 12, FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC PANEL DISCUSSION, MASTER CLASS AND OPEN REHEARSAL WILL CONTINUE THE GUARNERI’S 40TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS The world-renowned Guarneri String Quartet, one of the most esteemed and beloved ensembles of our time, will continue its 40th anniversary celebration by giving a gift to the people of New York City: a series of three events on Monday and Tuesday, April 11 and 12, in the Daniel and Joanna S. Rose Rehearsal Studio of Lincoln Center, which will be free and open to the public. The events include a master class involving top young string quartets from The Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute of Music, and the Manhattan School of Music; an open rehearsal for the Guarneri String Quartet’s Alice Tully Hall concert on April 13 presented by The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center; and a panel discussion with the members of the Guarneri Quartet, veteran members of historic string quartets, and members of the newest quartet generation. All three events will be held in the Rose Studio of the Rose Building (165 West 65th Street, 10th Floor; 65th Street and Amsterdam Avenue) and are free and open to the public on a first-come, first-served basis. Members of the Guarneri String Quartet are Arnold Steinhardt and John Dalley, violins; Michael Tree, viola; and Peter Wiley, cello. -

For Gershwin Lovers Everywhere.”

Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] J. Henry Fair Contents: Biography Mailing Address: 1000 South Denver Avenue Press Excerpts Suite 2104 Press Tulsa, OK 74119 Repertoire Website: YouTube Video Links http://www.pricerubin.com Photo Gallery Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Opus Two – Biography Opus Two has been internationally recognized for its “divine phrases, impelling rhythm, elastic ensemble and stunning sounds,” as well as its commitment to expanding the violin-piano duo repertoire. The award-winning duo, comprising violinist William Terwilliger and pianist Andrew Cooperstock, has been hailed for its “unanimity of style and spirit, exemplary balance and close rapport.” Opus Two first came to international attention as winners of the United States Information Agency’s Artistic Ambassador Auditions in 1993 and has since performed across six continents, including major tours of Europe, Australia, South American, Asia, and Africa. Their US engagements include performances at Carnegie Hall, where they performed Haydn’s Double Concerto for Violin and Piano, Lincoln Center, Merkin Hall and a standing-room-only recital at New York’s Library for the Performing Arts. State Department associations have taken them to Japan, Korea, Russia, Ukraine, Germany, France, Switzerland, Peru, Ghana, and Australia, and they have also held multiple residencies in China. The duo has presented master classes worldwide at a number of prestigious