Issues Related to Arab Muslim Identity, Nationalism And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AHA 2010 Freedom of Expression and the Rights of Women

www.theAHAfoundation.org FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN Political Islam’s threat to freedom of expression is bad for everyone, but hurts women the most December 2, 2010 Published by the AHA Foundation The AHA Foundation 130 7th Avenue, Suite 236, New York, NY 10011 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary & Recommendations 3 Introduction: The Price of Freedom of Expression 6 Section 1: The Importance of Freedom of Expression for the Rights of 7 Muslim Women in Western Countries Section 2: Political Islam and Multiple Levels of Pressure against Freedom 10 of Expression 1) Global Political Pressure 12 2) Lawsuits and Legal Tactics Pressuring Individuals—the Fight in the 25 Courts 3) Pressure through Physical Threats to Individuals 31 4) Internal Pressures: U.S. Institutions, Fear, and Self-Censorship 39 Section 3: The Effects of a Climate of Domination 48 Conclusion: A More Effective Response in the United States and Other 52 Western Countries References 55 2 Executive Summary Supporters of political Islam have launched a multifaceted assault on the principles of freedom in the West. Political Islam includes the establishment of Sharia (the body of Islamic religious law), which contains harsh restrictions on freedom of expression, as well as harsh punishments for apostasy and blasphemy and standards at odds with modern Western norms of gender equality. Political Islamists are actively attempting to extend the reach of Sharia over Western cultures and legal systems. This report addresses how, through means of actual physical violence, threats and intimidation, legal action, and political pressure, the emancipation of Muslim women is stunted if not ground to a halt. -

Sociology of Islam & Muslim Societies, Newsletter No. 3

Portland State University PDXScholar Sociology of Islam & Muslim Societies Newsletter International & Global Studies Fall 2008 Sociology of Islam & Muslim Societies, Newsletter No. 3 Tugrul Keskin Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/is_socofislamnews Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Keskin, Tugrul, "Sociology of Islam & Muslim Societies, Newsletter No. 3" (2008). Sociology of Islam & Muslim Societies Newsletter. 3. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/is_socofislamnews/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology of Islam & Muslim Societies Newsletter by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. SOCIOLOGY OF ISLAM & MUSLIM SOCIETIES ! FALL 2008 Newsletter No. 3 ISSN 1942-7948 VIRGINIA TECH - Department of Sociology 560 McBryde Hall Blacksburg, VA 24061 - USA Contents * Interview with Sherry Jones on Her Novel “The Jewel of Medina”, Islam and Free Speech * The Strange Case of the UIJ, or the evolutions of Uzbek Jihadism by Didier Chaudet * 'Hizb ut-Tahrir in Uzbekistan: A Postcolonial Perspective' by Reed Taylor * Islamic Banking by Husnul Amin Dear All, would like ind out who she really is. Random House cancelled the publication of her novel, It was a couple of weeks ago that I received The Jewel of Medina, as a result of a possible an email from a colleague of mine who was “terrorist” reprisal attack. On the other hand, telling me about a controversial novel written Pakistani‐born Kamran Pasha’s new novel, by Sherry Jones on the Prophet Muhammed’s Mother of the Believers will be released in (SAV) wife, Aisha. -

Federal Civil Rights Engagement with Arab & Muslim-Americans Post 9/11

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Federal Civil Rights Engagement with Arab and Muslim American Communities —POST 9/11 — BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business SEPTEMBER 2014 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Martin R. Castro, Chairman bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Abigail Thernstrom, Vice Chair (term expired November 2013) directed to: Roberta Achtenberg Todd F. Gaziano (term expired December 2013) • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Gail L. Heriot being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their Peter N. Kirsanow race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national David Kladney origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Marlene Sallo, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 1331 Pennsylvania Ave NW Suite 1150 • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to Washington, DC 20425 discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or (202) 376-7700 national origin, or in the administration of justice. www.usccr.gov • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. -

Reading Orientalism in Sherry Jones' the Jewel Of

GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 169 Volume 19(4), November 2019 http://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2019-1904-09 (Un)reading Orientalism in Sherry Jones’ The Jewel of Medina Sadiya Abubakar [email protected] School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia Md. Salleh Yaapar [email protected] School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia Suzana Muhammad [email protected] School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia ABSTRACT Oriental representations of Muslims are often manifested in a society's media, literature, theatre and other creative means of expression. However, these representations, which are often historically and conceptually one-sided, have adverse repercussions for Muslims today, potentially leading to Islamophobia. Orientalism of Muslims in Western writings and discourses have been much discussed, debated and disproved, yet some works of literature continue to disseminate many of the earlier Oriental assertions about Islam/Muslims: that of being terrorists, misogynists, barbaric or uncivilized compared to the civilized West. Sherry Jones’ The Jewel of Medina (2008) chronicles the history of Islam from the time of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad, through the voice of his youngest wife Aisha. This paper argues that there is more to the image of the Muslim than what is portrayed by Western writers. Through an “(un)reading” of Sherry Jones’ text, this paper unravels the misconceptions regarding early and forced marriage with a view to address the ways in which these misconceptions could lead to Islamophobia. Using Edward Said's theory of Contrapuntal reading, which urges the colonized to unread Western canonical texts to unearth the submerged details, this paper identifies and puts to question non-conforming depictions of Muslims in Sherry Jones’ The Jewel of Medina (2008) – while placing the text in its historical space – in an effort to mitigate the growing stereotyping of Muslims and to address misconceptions with regard to Islamic history. -

British Jihadism: the Detail and the Denial

British Jihadism: The Detail and the Denial Paul Vernon Angus Stott A thesis submitted to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of East Anglia School of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies 30 April 2015. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract Since the early 1990s British Islamists have been fighting, killing and dying in a succession of conflicts across the world, beginning with the Bosnian civil war of 1992-95. A decade later this violence reached the United Kingdom, with a series of deadly attacks on the London transport system in July 2005, the first suicide bombings in Western Europe. This thesis provides a historiography of the involvement of Britons in global and domestic jihadist struggles at home and abroad across three decades. It catalogues and records their actions, and bring into a central document the names and affiliations of both British Islamist combatants, and those from jihadist organisations who have settled in this country. The ever increasing number of Britons travelling to the Islamic State does not come as a surprise when the scale of past involvement in such causes is considered. This thesis deconstructs the religious objectives is intrinsic to these trends, and emphasises that in British Jihadism it is the goal, as much as the message, which is religious. -

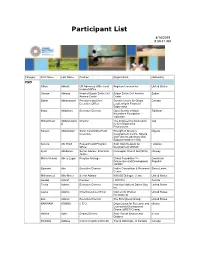

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Sufism in the Secret History of Persia ♣

SUFISM IN THE SECRET HISTORY OF PERSIA ♣ Gnostica Texts and Interpretations Series Editors Garry Trompf (Sydney), Jason BeDuhn (Northern Arizona) and Jay Johnston (Sydney) Advisory Board Antoine Faivre (Paris), Iain Gardner (Sydney), Wouter Hanegraaff (Amsterdam), Jean-Pierre Mahé (Paris), Raol Mortley (Newcastle) and Brikha Nasoraia (Mardin) Gnostica publishes the latest scholarship on esoteric movements, including the Gnostic, Hermetic, Manichaean, Theosophical and related traditions. Contributions also include critical editions of texts, historical case studies, critical analyses, cross- cultural comparisons and state-of-the-art surveys. Published by and available from Acumen Sufism in the Secret History of Persia Milad Milani Histories of the Hidden God: Concealment and Revelation in Western Gnostic, Esoteric, and Mystical Traditions Edited by April DeConick and Grant Adamson Contemporary Esotericism Edited by Egil Asprem and Kennet Granholm Angels of Desire: Esoteric Bodies, Aesthetics and Ethics Jay Johnston Published by Peeters Schamanismus und Esoterik: Kutlur- und wissenschaftsgeschichtliche Betrachtungen Kocku von Stuckrad Ésotérisme, Gnoses et imaginaire symbolique: Mélanges offerts à Antoine Faivre Edited by Richard Caron, Joscelyn Godwin, Wouter Hanegraaff and Jean-Louis Vieillard-Baron Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion Edited by Antoine Faivre and Wouter Hanegraaff Adamantius, Dialogues on the True Faith in God Translation and commentary by Robert Pretty SUFISM IN THE SECRET HISTORY OF PERSIA MILAD MILANI First published 2013 by Acumen Published 2014 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © Milad Milani, 2013 This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. -

The Free Speech Protection Act of 2008

THE FREE SPEECH PROTECTION ACT OF 2009: PROTECTION AGAINST SUPPRESSION INTRODUCTION In 2003, Dr. Rachel Ehrenfeld published a book in the United States titled Funding Evil: How Terrorism is Financed—and How to Stop It.1 In the book, she alleged that a wealthy Saudi Arabian businessman named Khalid Salim Bin Mahfouz was funding al Qaeda and other terrorists.2 The British publisher cancelled its deal with Ehrenfeld after receiving a threat of a lawsuit by an unnamed Saudi.3 After the book was published in the United States, Mahfouz‘s lawyers asked Ehrenfeld to retract what she said, but she refused.4 Mahfouz filed suit against Ehrenfeld in England for libel, asserting English courts had jurisdiction over her based on twenty-three copies of the book that had been purchased in England over the Internet and a chapter posted on an ABCNews.com website available in England.5 Ehrenfeld chose not to appear to contest the suit on advice of English counsel, and received a judgment against her for $225,000.6 Ehrenfeld accepted the default judgment because she believed it was better than dealing with the high cost of litigation and procedural barriers in England, and because of her disagreement in principle with being sued in a libel-friendly jurisdiction where she did not even make the speech at issue.7 Ehrenfeld instead filed a suit of her own in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, seeking a declaratory judgment that Mahfouz could not prevail based on the allegedly libelous statements at issue and that the English judgment was not enforceable in the United States or New York.8 The district court held that it lacked personal jurisdiction over Mahfouz based on a New York long-arm statute.9 In response to a certified question to the U.S. -

Sibling Rivalry on a Royal Scale Four Sisters of the House of Savoy C C

C C Sibling Rivalry on a Royal Scale four sisters of the House of Savoy C C Marguerite. Eléonore. Sanchia. Beatrice. These four sisters, Although Dante credits the count and countess’s steward, members of the prestigious House of Savoy, made history in the Romeo de Villeneuve, with the sisters’ marriages to kings, Beatrice 13th century when they all became queens – of France, England, of Savoy’s influence cannot be overlooked. After all, she had Germany, and Italy. eight brothers, of whom seven were essentially landless. Given Arguably the most famous women in the Western world her involvement in her daughters’ lives until her death, it’s certain during their lifetimes – praised in the chansons of the Southern that she played an important role in their marriages to kings troubadours, mentioned in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, lauded by and future kings. Not for nothing did she have them schooled chroniclers for their incomparable beauty – the sisters of Savoy in the trivium and quadrivium, comprising the seven liberal arts also might have been, as a group, the most powerful. of grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy Working together was the key to their and music. This type of education, almost success, as their mother, Beatrice of Savoy, always reserved for boys, gave her “boys,” as had doubtless told them many times. Had she supposedly called them, an edge when they continued to do so, they might have it came to meeting the demands of courtly made remarkable accomplishments for life. Indeed, it probably helped Marguerite their kingdoms and their family. Indeed, impress the King of France’s envoy, Giles Marguerite and Eléonore, the eldest sisters, de Flagy, on his visit to Aix-en-Provence to worked together with the younger Sanchia inspect her as a potential bride. -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2008

AL Direct, September 3, 2008 Contents U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online Division News Awards Seen Online Tech Talk Publishing The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | September 3, 2008 Actions & Answers Calendar U.S. & World News Director: Library Diaries author invaded patrons’ privacy The director of the Mason County (Mich.) District Library contends that he did not violate the First Amendment rights of a library assistant he fired in late July after reading her unflattering book about the quirky and disreputable characters who populate ALA Midwinter Meeting, The Library Diaries. Robert Dickson told American Denver, January 23–28. Libraries that “every single character in the book is a New this year: You must specific, identifiable person with nothing changed register for the Midwinter [except their names],” some 15–20 of which are real-life patrons of Meeting before you can the Ludington library Dickson heads and at which author Sally Stern- register for housing. Hamilton worked for 15 years. “The information she’s learned about these people over the years was revealed in the book, and our immediate reaction was that this was an invasion of privacy.”... American Libraries Online, Aug. 30 City won’t seek jail for It’s Perfectly Normal protester A standoff of more than a year ended August 29 in Lewiston, Maine, when city officials decided not to pursue further action against JoAn Karkos (right), who has refused to return the Lewiston Public Library’s copy of the youth sex-education When writing the first book It’s Perfectly Normal that she borrowed in the summer of 2007 edition of Teen to keep it out of circulation. -

|||GET||| the Jewel of Medina a Novel 1St Edition

THE JEWEL OF MEDINA A NOVEL 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Sherry Jones | 9780825305184 | | | | | [PDF] The Jewel of Medina Book by Sherry Jones Free Download (358 pages) She is currently the Montana and Idaho correspondent for the Bureau of National Affairs, an international news agency in the Washington, D. Archived from the original on February 18, The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved October 14, Topics Fiction Book of the week news Reuse this content. The Jewel of Medina A Novel 1st edition Rating:. Beaufort Books. Refresh and try again. The Jewel of Medina : A Novel. Editions Showing of Your Comment:. La joya de Medina Hardcover. Medinas juvel Hardcover. A spokesman for Gibson Square suggested that the author had now decided the best thing to do was to postpone both her visit, which was scheduled for October 16 to 19, and publication of the book, which was due on October Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Random House signed Sherry Jones to a two-book contract inoffering her an advance of one hundred thousand dollars, [5] with The Jewel of Medina scheduled to be released on August 12, The Jewel of Medina A Novel 1st edition Again blog. Book of the week Fiction. The Times. The Neighbor by Lisa Gardner. Gibson House website. Visit cancelled: Jewel of Medina author Sherry Jones. January Aisha Das Juwel von Medina Paperback. The Wall Street Journal. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. A'isha bint Abi Bakr is the daughter of a rich merchant from Mecca in the harsh, exotic world of seventh-century Arabia at the time of the foundation of Islam. -

The Rushdie Affair in Britain

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2012 Dancing with a Literary Devil: The Rushdie Affair in Britain Arjun Mishra Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Mishra, Arjun, "Dancing with a Literary Devil: The Rushdie Affair in Britain" (2012). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 181. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/181 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dancing with a Literary Devil: The Rushdie Affair in Britain A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Arjun Mishra Candidate for BA Degree and Renée Crown University Honors May 2012 Honors Capstone Project in History Capstone Project Advisor: _______________________ Advisor Title & Name Capstone Project Reader: _______________________ Reader Title & Name Honors Director: _______________________ Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: May 2, 2012 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Michael Ebner of the History Department for guiding me through this project and working with me for the past two years. He deserves special praise for undertaking and supervising this project, given that the project strays far away from his country, time period, and topics of expertise. For all of his help and insights as a professor and supervisor the past two and half years, I am very grateful.