The Old Malay Mañjuśrīgr̥ha Inscription from Candi Sewu (Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

Theme 4C the Role and Importance of Dana (Giving) and Punya (Merit)

EDUQAS AS Component 1D: An Introduction to Buddhism - Knowledge Organiser: Theme 4C The role and importance of dana (giving) and punya (merit) Key concepts • The understanding of punya is more complex in Mahayana. One understanding is that the bodhisattva can transfer merit to the person who is invoking/praying to them and thus • Dana (giving) is the first of the ten paramitas (perfections) and in Theravada is regarded help them in this life and in gaining a good/better rebirth. The bodhisattva Avalokitesvara as fundamental to meritorious actions (punnakiriyavatthu) and to benefitting others thus transfers merit to all who call on him/her. A similar concept can be found in Pure Land (sanghavatthu). Dana in particular can help prevent development of one of the Three Buddhism with the focus on Amida Buddha providing believers with merit to progress. Poisons – greed. • Dana is important because it sanghavatthu encourages detachment and helps to overcome tanha (clinging). It is the sappurisa (good/superior person) who is able to offer Key quotes dana especially when dana is given with caga (generosity). How a person gives dana is always important – is it done with a good intention, with wisdom and with generosity? ‘He who gives alms, bestows a fourfold blessing: he helps to long life, good appearance, • Dana always involves the giver gaining kamma for their wholesome act but this should happiness and strength.’ (Anguttara Nikaya) not be the intention behind giving. The purity of the recipient of dana is very important ‘The practice of giving is universally recognised as one of the most basic human virtues, a here and can be seen in five categories: (1) the best dana is to an arhat or the monastic quality that testifies to the depth of one’s humanity and one’s capacity for self-transcendence.’ Sangha; (2) a monk or nun who is on the arhat path; (3) a Buddhist who has taken the (Bhikkhu Bodhi) five precepts; (4) people who are not spiritually advanced; (5) the least effective dana is to immoral people. -

The Ultimate Origin of the World, Or the Mula Muh, and Other Mon Beliefs*

THE ULTIMATE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD, OR THE MULA MUH, AND OTHER MON BELIEFS* EMMANUEL GUILLON FORMER CHARGE DE CONFERENCE ECOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ETUDES SECTION DES SCIENCES RELIGEUSES PARIS Can we credit the Mons with possessing a world view, a The first things that came into being were the seasons, hot mental universe, a landscape of feelings and emotions, which and cold. They both appeared at once and were followed by we can deduce from their myths, beliefs and rites, and which a wind that never ceased blowing. The air expanded until it thus is uniquely their own? Since we are by no means deal became an enormous mass. Then the water appeared and ex ing with a human isolate (if indeed such a thing has ever panded also. A mist began to rise up from the water and existed), we will inevitably encounter a network of foreign then fell as rain. The dry season evaporated the water and influences. But such influences often are modified by the the land appeared. The land was able to produce stones and genius of a language and a people. Does there still survive, minerals, and silver, gold, iron, tin and copper soon appeared then, some explanation of the world that can be considered as well as the various precious stones. Then the first kinds of uniquely characteristic of the Mons? vegetation appeared on the gold ore as a kind of moss, fol lowed by grass and all the other plants of the vegetable Mula Muh kingdom. There,does exist, in fact, a cosmology of which we have "The four elements had the propensity to produce living beings. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

The Fundamentals of Meditation Practice

TheThe FundamentalsFundamentals ofof MeditationMeditation PracticePractice by Ting Chen Translated by Dharma Master Lok To HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Fundamentals of Meditation Practice by Ting Chen Translated by Dharma Master Lok To Edited by Sam Landberg & Dr. Frank G. French 2 Transfer-of-Merit Vow (Parinamana) For All Donors May all the merit and grace gained from adorning Buddha’s Pure Land, from loving our parents, from serving our country and from respecting all sen- tient beings be transformed and transferred for the benefit and salvation of all suffering sentient be- ings on the three evil paths. Furthermore, may we who read and hear this Buddhadharma and, there- after, generate our Bodhi Minds be reborn, at the end of our lives, in the Pure Land. Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada, 1999 — website: http://www.ymba.org/freebooks_main.html Acknowledgments We respectfully acknowledge the assistance, support and cooperation of the following advisors, without whom this book could not have been produced: Dayi Shi; Chuanbai Shi; Dr. John Chen; Amado Li; Cherry Li; Hoi-Sang Yu; Tsai Ping Chiang; Vera Man; Way Zen; Jack Lin; Tony Aromando; and Ling Wang. They are all to be thanked for editing and clarifying the text, sharpening the translation and preparing the manuscript for publication. Their devotion to and concentration on the completion of this project, on a voluntary basis, are highly appreciated. 3 Contents • Translator’s Introduction...................... 5 • The Foundation of Meditation Practice. -

Starting from SGD 799 Per Pax, 6-To-Go! Departing on Selected Dates, Check with Us for More Details!

5 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_14Mar19- Page 1 of 2 The largest Mahayana structure in the world is located deep in the middle of South East Asia! Join us on a trip to Borobudur and be regaled by stories of the Buddha’s life (and previous lives), Bodhisattvas and Sudhana’s journeys (as depicted in the Lalitavistara, Avatamsaka Sutra, the Jatakamala and the Divyavadana). Package price: starting from SGD 799 per pax, 6-to-go! Departing on selected dates, check with us for more details! INCLUDES: EXCLUDES: 1. Private guided tour 1. All domestic and international flights ** 2. Airport pickups and drop-offs 2. Travel insurance ** 3. Transfers between places 3. Visas ** 4. Guides and entrance fees 4. Optional excursions 5. Excursions and meals as listed in the itinerary 5. Tips (guides and drivers) 6. Meals as listed in the itinerary 6. Alcoholic drinks 7. Accommodation 7. Personal expenses (three-star hotel, twin sharing) (** can be arranged through us upon request) Itinerary: (depends on arrival) Day 01 – ARRIVAL IN YOGYAKARTA (Lunch & dinner included) Depart from Singapore to Yogyakarta by flight. Check in to hotel and have lunch after arrival. Afternoon – Visit Prambanan Temple Compounds, Candi Lumbung, Candi Bubrah and Candi Sewu Night – Check-in hotel, rest for the day TRAVELLING WITH WISDOM - BODHI TRAVEL ● 5 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_14Mar19 Email: [email protected] │ Phone: (65) 6933 9908 │ WhatsApp: (65) 8751 4833 │ https://www.bodhi.travel 5 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_14Mar19- Page 2 of 2 Day 02 – CANDI BOROBUDUR -

BODHI TRAVEL 4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour 05Nov19

4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_05Nov19- Page 1 of 2 The largest Mahayana structure in the world is located deep in the middle of South East Asia! Join us on a trip to Borobudur and be regaled by stories of the Buddha’s life (and previous lives), Bodhisattvas and Sudhana’s journeys (as depicted in the Lalitavistara, Avatamsaka Sutra, the Jatakamala and the Divyavadana). INCLUDES: EXCLUDES: 1. Private guided tour 1. Travel insurance ** 2. Airport pickups and drop-offs 2. Visas ** 3. Transfers between places (with air-cond) 3. Optional excursions 4. Guides and entrance fees 4. Tips (guides and drivers) 5. Excursions and meals as listed in the itinerary 5. Alcoholic drinks 6. Meals as listed in the itinerary 6. Personal expenses 7. Accommodation (four-star hotel, twin sharing) (** can be arranged through us upon request) 8. Round trip flight tickets (SIN – YOG) Itinerary: (this is our template itinerary, please let us if any customisation is needed) Day 01 – ARRIVAL IN YOGYAKARTA (Lunch & dinner included) AirAsia – departs daily – 1110hrs to 1230hrs (tentative) Depart from Singapore to Yogyakarta by flight. Have lunch after arrival. Afternoon – Visit Prambanan Temple Compounds, Candi Lumbung, Candi Bubrah and Candi Sewu Night – Check-in hotel and early rest Day 02 – CANDI BOROBUDUR (Breakfast@hotel, lunch & dinner included) Morning – Sunrise at Candi Borobudur (wake up at 4am), Guided tour at Candi Borobudur Afternoon – Visit Candi Pawon and Candi Mendut, Bike ride tour at village (optional) Night – Free and easy, rest for the day TRAVELLING WITH WISDOM - BODHI TRAVEL ● 4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_05Nov19 Email: [email protected] │ WhatsApp: (65) 8751 4833 │ https://www.bodhi.travel 4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_05Nov19- Page 2 of 2 Day 03 – VISIT TO MOUNT MERAPI (Breakfast@hotel, lunch & dinner included) Morning – Visit to Mount Merapi (Jeep ride) and House of Memories Afternoon – Return to Yogyakarta (max. -

The Concept of Existence (Bhava) in Early Buddhism Pranab Barua

The Concept of Existence (Bhava) in Early Buddhism Pranab Barua, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand The Asian Conference on Ethics, Religion & Philosophy 2021 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The transition in Dependent Origination (paṭiccasamuppāda) between clinging (upādāna) and birth (jāti) is often misunderstood. This article explores the early Buddhist philosophical perspective of the relationship between death and re-birth in the process of following bhava (uppatti-bhava) and existing bhava (kamma-bhava). It additionally analyzes the process of re- birth (punabbhava) through the karmic processes on the psycho-cosmological level of becoming, specifically how kamma-bhava leads to re-becoming in a new birth. The philosophical perspective is established on the basis of the Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-Sutta, the Mahāvedalla-Sutta, the Bhava-Sutta (1) and (2), the Cūḷakammavibhaṅga-Sutta, the Kutuhalasala-Sutta as well as commentary from the Visuddhimagga. Further, G.A. Somaratne’s article Punabbhava and Jātisaṃsāra in Early Buddhism, Bhava and Vibhava in Early Buddhism and Bhikkhu Bodhi’s Does Rebirth Make Sense? provide scholarly perspective for understanding the process of re-birth. This analysis will help to clarify common misconceptions of Tilmann Vetter and Lambert Schmithausen about the role of consciousness and kamma during the process of death and rebirth. Specifically, the paper addresses the role of the re-birth consciousness (paṭisandhi-viññāṇa), death consciousness (cūti-viññāṇa), life continuum consciousness (bhavaṅga-viññāṇa) and present consciousness (pavatti-viññāṇa) in the context of the three natures of existence and the results of action (kamma-vipāka) in future existences. Keywords: Bhava, Paṭiccasamuppāda, Kamma, Psycho-Cosmology, Punabbhava iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Prologue Bhava is the tenth link in the successive flow of human existence in the process of Dependent Origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). -

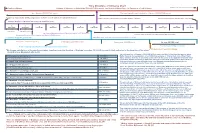

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

EMERGENCY SHELTER REQUIRED Legend

110°0'0"E 110°12'0"E 110°24'0"E 110°36'0"E 110°48'0"E KOTA BOYOLALI SURAKARTA Pucang Miliran Tegalmulyo Sudimoro S S Tulung " " Balerante Daleman 0 0 Sidomulyo MAGELANG Mundu ' ' Tlogowatu Tegalgondo Kemiri Gedongjetis Cokro 6 6 Kayumas Beji Bolali Polanharjo Wadung 3 3 Sedayu Segaran Dalangan Kebonharjo ° ° Pandanan Teloyo Turi Pomah Wangen Kranggan Getas Sukorejo 7 7 Majegan Keprabon Kemalang Bandungan Karanglo Gatak Mendak Sekaran Kendalsari Socokangsi Kiringan Jeblog De lan ggu Boto KLATEN Gempol Turus Krecek Bentangan Kingkang Panggang Glagah Bonyokan Pondok Nganjat Sabrang Tlobong Dompol Kauman Karang Lumbung Kerep SLEMAN Jatinom Gledeg Pundungan Jurangjero Ngemplak Ngaran Banaran Wonosari Bengking Jatinom Gunting Bawukan Jiwan Glagah Wangi Talun Karanganom Jetis Ju w irin g Logede Kunden Randulanang Karangan Trasan Juwiring Carikan Ngemplak Kemalang Kahuman Jungkare Jaten Kalibawang Cangkringan Gemampir Kwarasan Taji Samigaluh Kepurun Seneng Tempursari Troso Bulurejo Tanjung Donokerto Blanceran Bolopleret Manisrenggo Kanoman Blimbing Ngawonggo Juwiran Kenaiban Sapen Keputran Ngawen Jambu Tambak Rejo Pakem Jagalan Ceper Tlogorandu Serenan Duwet Ngawen Mayungan Kulon Lemahireng Jetis Harjo Binangun Karangnongko Dlimas Kaligawe Kadilajo Jetis Belang Jombor Kurung Leses Gergunung Kebonalas Sukorini Karangduren Wetan Pokak Cetan Pedan Manjung Klaten Utara Kalangan Tegalampel Triharjo Banyuaeng Malangjiwan Bareng Kujon Jambu Sobayan Karangwungu Babadan Bendan Gumul Sekarsuli Mlese Pandowo Suko Kranggan Kidul Sentono Karangtalun Tempel -

The Special Theory of Pratītyasamutpāda: the Cycle Of

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A.K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS tL. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University oj Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universile de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson Fairfield University Fairfield, Connecticut, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 1 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES The Meaning of Vijnapti in Vasubandhu's Concept of M ind, by Bruce Cameron Hall 7 "Signless" Meditations in Pali Buddhism, by Peter Harvey 2 5 Dogen Casts Off "What": An Analysis of Shinjin Datsuraku, by Steven Heine 53 Buddhism and the Caste System, by Y. Krishan 71 The Early Chinese Buddhist Understanding of the Psyche: Chen Hui's Commentary on the Yin Chihju Ching, by Whalen Im 85 The Special Theory of Pratityasamutpdda: The Cycle of Dependent Origination, by Geshe Lhundub Sopa 105 II. BOOK REVIEWS Chinese Religions in Western Languages: A Comprehensive and Classified Bibliography of Publications in English, French and German through 1980, by Laurence G. Thompson (Yves Hervouet) 121 The Cycle of Day and Night, by Namkhai Norbu (A.W. Hanson-Barber) 122 Dharma and Gospel: Two Ways of Seeing, edited by Rev. G.W. Houston (Christopher Chappie) 123 Meditation on Emptiness, by Jeffrey Hopkins Q.W. de Jong) 124 5. Philosophy of Mind in Sixth Century China, Paramdrtha 's 'Evolution of Consciousness,' by Diana Y. Paul (J.W.deJong) 129 Diana Paul Replies 133 J.W.deJong Replies 135 6.