Human Rights & Foreign Investment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chair of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (Ms

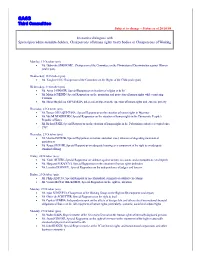

GA65 Third Committee Subject to change – Status as of 8 October 2010 Special procedure mandate-holders, Chairs of human rights treaty bodies or Chairs of Working Groups presenting reports Monday, 11 October (am) Chair of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (Ms. Xiaoqiau ZOU, Vice-Chair, on behalf of Ms. Naela GABR, Chair of CEDAW) – oral report and interactive dialogue. Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Ms. Rashida MANJOO – oral report Wednesday, 13 October (pm) Special Representative of the Secretary-General on violence against children, Ms. Marta SANTOS PAIS. Chair of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, Ms. Yanghee LEE - oral report. Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Ms. Najat M’jid MAALLA Monday, 18 October (am) Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedom of indigenous people, Mr. James ANAYA Tuesday, 19 October (am) Chair of the Committee against Torture, Mr. Claudio GROSSMAN – oral report and interactive dialogue. Chair of the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, Mr. Victor Manuel RODRIGUEZ RESCIA – oral report and interactive dialogue. Wednesday, 20 October (pm) Independent Expert on minority issues, Ms. Gay McDOUGALL. Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Mr. Tomas Ojea QUINTANA. Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Mr. Richard FALK. Thursday, 21 October (am) Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Mr. Olivier DE SCHUTTER. Independent expert on the effects of foreign debt and other related international financial obligations of States on the full enjoyment of human rights, particularly economic, social and cultural rights, Mr. -

Special Procedure Mandate-Holders Presenting to the Third Committee

GA66 Third Committee Subject to change – Status as of 7 October 2011 Special procedure mandate-holders, Chairs of human rights treaty bodies or Chairs of Working Groups presenting reports Monday, 10 October (am) • Chair of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Ms. Silvia Pimentel – oral report and interactive dialogue. • Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Ms. Rashida MANJOO report and interactive dialogue. Wednesday, 12 October (pm) • Chair of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, Mr. Jean Zermatten, – oral report. • Special Representative of the Secretary-General on violence against children, Ms. Marta SANTOS PAIS. • Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, Ms. Najat M’jid MAALLA. Monday, 17 October (am) • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Mr. James ANAYA. Tuesday, 18 October (am) • Chair of the Committee against Torture, Mr. Claudio GROSSMAN – oral report and interactive dialogue. • Chair of the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, Mr. Malcolm David Evans – oral report and interactive dialogue. • Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of punishment, Mr. Juan MENDEZ Wednesday, 19 October (pm) • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, Mr. Ahmed SHAHEED. • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Mr. Tomas Ojea QUINTANA. • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Mr. Marzuki DARUSMAN. Thursday, 20 October (am) • Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, Mr. -

If Rio+20 Is to Deliver, Accountability Must Be at Its Heart

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT DES NATIONS UNIES OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PROCEDURES SPECIALES DU SPECIAL PROCEDURES OF THE CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L’HOMME HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL IF RIO+20 IS TO DELIVER, ACCOUNTABILITY MUST BE AT ITS HEART An Open Letter from Special Procedures mandate-holders of the Human Rights Council to States negotiating the Outcome Document of the Rio+20 Summit As independent experts of the Human Rights Council, we call on States to incorporate universally agreed international human rights norms and standards in the Outcome Document of the Rio+20 Summit with strong accountability mechanisms to ensure its implementation.1 The United Nations system has been building progressively our collective understanding of human rights and development through a series of key historical moments of international cooperation, from the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights in December 1948 to the Millennium Declaration in September 2000 that inspired the Millennium Development Goals to the and the World Summit Outcome Document in October 2005. Strategies based on the protection and realization of all human rights are vital for sustainable development and the practical effectiveness of our actions. A real risk exists that commitments made in Rio will remain empty promises without effective monitoring and accountability. We offer proposals as to how a double accountability mechanism can be established. At the international level, we support the proposal to establish a Sustainable Development Council to monitor progress towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be agreed by 2015. -

Appendix K. UN and Regional Special Procedures

Appendix K: UN and Regional Special Procedures Appendix K. UN and Regional Special Procedures UN Special Procedures Special Procedure Name Contact / Special instructions Independent Expert on minority Ms. Rita Izsák [email protected] issues Tel: +41 22 917 9640 Independent Expert on human Ms. Virginia Dandan [email protected] rights and international Telephone: (41-22) 928 9458 solidarity Fax: (+41-22) 928 9010 Independent Expert on the effects Mr. Cephas Lumina [email protected] of foreign debt Independent Expert on the issue Mr. John Knox [email protected] of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment Independent Expert on the Mr. Alfred de Zayas [email protected] promotion of a democratic and equitable international order Independent Expert on the Mr. Shamsul Bari [email protected] situation of human rights in Somalia Independent Expert on the Mr. Mashood Baderin [email protected] situation of human rights in the Sudan Independent Expert on the Mr. Doudou Diène [email protected] situation of human rights in Côte d’Ivoire Independent Expert on the Mr. Gustavi Gallón [email protected] situation of human rights in Haiti Special Rapporteur in the field of Ms. Farida Shaheed [email protected] cultural rights Telephone: (41-22) 917 92 54 Special Rapporteur on adequate Ms. Raquel Rolnik [email protected] housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living Special Rapporteur on Mr. Mutuma Ruteere [email protected] contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Special Rapporteur on Ms. Gulnara Shahinian [email protected] contemporary forms of slavery, Special form: including its causes and its http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Is consequences sues/Slavery/SR/AFslavery_en.do c K-1 Appendix K: UN and Regional Special Procedures Special Procedure Name Contact / Special instructions Special Rapporteur on Mr. -

Catalysts for Rights: the Unique Contribution of the UN’S Independent Experts on Human Rights

Foreign Policy October 2010 at BROOKINGS Catalysts for for Catalysts r ights: The Unique Contribution of the UN’s Independent Experts on Human Rights the UN’s of Unique Contribution The Catalysts for rights: The Unique Contribution of the UN’s Independent Experts on Human Rights TEd PiccoNE Ted Piccone BROOKINGS 1775 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20036 www.brookings.edu Foreign Policy October 2010 at BROOKINGS Catalysts for rights The Unique Contribution of the U.N.’s Independent Experts on Human Rights Final Report of the Brookings Research Project on Strengthening U.N. Special Procedures TEd PiccoNE The views expressed in this report do not reflect an official position of The Brookings Institution, its Board, or Advisory Council members. © 2010 The Brookings Institution TABLE oF CoNTENTS acknowledgements . iii Members of Experts advisory group . v list of abbreviations . vi Executive summary ....................................................................... viii introduction . 1 Context . 2 Methodology . 3 A Short Summary of Special Procedures . 5 summary of findings . 9 Country Visits . .9 Follow-Up to Country Visits..............................................................19 Communications . 20 Resources . 31 Joint Activities and Coordination . .32 Code of Conduct . 34 Training . .34 Universal Periodic Review...............................................................35 Relationship with Treaty Bodies . 36 recommendations..........................................................................38 Appointments . 38 Country Visits and Communications .......................................................38 Follow-Up Procedures . 40 Resources . .41 Training . .41 Code of Conduct . 42 Relationship with UPR, Treaty Bodies, and other U.N. Actors . .42 appendices Appendix A HRC Resolution 5/1, the Institution Building Package ...........................44 Appendix B HRC Resolution 5/2, the Code of Conduct . .48 Appendix C Special Procedures of the HRC - Mandate Holders (as of 1 August 2010) . -

Third Committee Subject to Change – Status As of 20/10/08

GA63 Third Committee Subject to change – Status as of 20/10/08 Interactive dialogues with Special procedure mandate-holders, Chairpersons of human rights treaty bodies or Chairpersons of Working Monday, 13 October (am) • Ms. Dubravka SIMONOVIC , Chairperson of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (oral report) Wednesday, 15 October (pm) • Ms. Yanghee LEE, Chairperson of the Committee on the Rights of the Child (oral report) Wednesday, 22 October (pm) • Ms. Asma JAHANGIR, Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief • Mr. Martin SCHEININ, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism • Ms. Maria Magdalena SEPULVEDA, Independent Expert on the question of human rights and extreme poverty Thursday, 23 October (am) • Mr. Tomas OJEA QUINTANA , Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar • Mr. Vitit MUNTARBHORN, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea • Mr. Richard FALK, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967 Thursday, 23 October (pm) • Mr. Manfred NOWAK, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment • Ms. Raquel ROLNIK, Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living Friday, 24 October (am) • Ms. Yakin ERTÜRK, Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences (oral report) • Ms. Margaret SEKAGGYA, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders • Mr. Leandro DESPOUY , Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers Friday, 24 October (pm) • Mr. Philip ALSTON , Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions • Mr. -

The Obligation to Mobilise Resources: Bridging Human Rights, Sustainable Development Goals, and Economic and Fiscal Policies

The Obligation to Mobilise Resources: Bridging Human Rights, Sustainable Development Goals, and Economic and Fiscal Policies December 2017 A report of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute Table of contents Foreword 4 Acknowledgements 7 Executive summary 9 The obligation to mobilise resources: legal basis and guiding principles 10 Sources of resource mobilisation 12 Addressing resource diversion and foregone tax revenues 12 The obligation to mobilise resources in action: opportunities and challenges 13 Recommendations 13 Acronyms and clarifications 16 Acronyms 16 Clarifications 18 Chapter 1: Introduction and background 20 1.1 Context and objectives 20 1.2 Scope, limitations and clarification 21 Special procedures and treaty bodies’ legal bearing 21 Limitations 25 Chapter 2: Obligation to mobilise resources for human rights realisation: legal basis and guiding principles 26 2.1 Legal basis of the obligation to mobilise resources 26 The obligation to take steps 27 The obligation to devote maximum available resources 28 What are ‘resources’? 28 December 2017 The Obligation to Mobilise Resources: Bridging Human Rights, Sustainable Development Goals, and Economic and Fiscal Policies 1 When are resources available? 30 IS RESOURCE MOBILISATION RELEVANT ONLY TO ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS? 30 The obligation to seek and provide international assistance and cooperation 32 Obligations of ‘those in a position to assist’ 33 Obligations for those in need of resources: seeking international assistance and cooperation 35 -

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights |

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights | www.ohchr.org United Nations Special Procedures FFAACCTTSS AANNDD FFIIGGUURREESS 22001133 Communications · Country visits · Coordination and joint activities Reports · Public statements and news releases· Thematic events Published by: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Geneva, February 2014 Pictures on front cover: Ms. Farida Shaheed, Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, speaking during her country visit to Vietnam. A wide view of the Human Rights Council room XX on the opening day of the Second Forum on business and human rights. Ms. Maria Magdalena Sepúlveda Carmona, Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights during her country visit to Moldova. Ms. Joy Ngozi Ezeilo, Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children and Mr. Pablo de Greiff, Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence, speaking during interactive dialogue at the General Assembly – New York October 2013. Mr. Frank La Rue, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, during his presentation to the Security Council, December 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ………………………………… 1 List of mandates and mandate-holders ….. 2 Developments in 2013…………………… 6 Communications …………………………... 10 Country visits …………………………….... 13 Positive developments…………………….. 16 Reports ……………………………………... 19 News releases ……………………………… 28 Basic figures at a glance…………………… 43 “Special Procedures Facts and Figures 2013” provides a general overview of the main activities of the Special Procedures mandate holders in 2013. This tool is produced by the Special Procedures Branch of the Human Rights Council and Special Procedures Division of OHCHR. -

Asamblea General Distr

NACIONES UNIDAS A Asamblea General Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/10/24 17 de noviembre de 2008 ESPAÑOL Original: INGLÉS CONSEJO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS Décimo período de sesiones Tema 3 del programa PROMOCIÓN Y PROTECCIÓN DE TODOS LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS, CIVILES, POLÍTICOS, ECONÓMICOS, SOCIALES Y CULTURALES, INCLUIDO EL DERECHO AL DESARROLLO Nota de la Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos La Alta Comisionada de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos tiene el honor de transmitir a los miembros del Consejo de Derechos Humanos el informe de la 15ª reunión de los relatores y representantes especiales, expertos independientes y presidentes de los grupos de trabajo encargados de los procedimientos especiales del Consejo, que se celebró en Ginebra del 23 al 27 de junio de 2008. GE.08-16827 (S) 121208 161208 A/HRC/10/24 página 2 INFORME DE LA 15ª REUNIÓN DE LOS RELATORES Y REPRESENTANTES ESPECIALES, EXPERTOS INDEPENDIENTES Y PRESIDENTES DE LOS GRUPOS DE TRABAJO ENCARGADOS DE LOS PROCEDIMIENTOS ESPECIALES DEL CONSEJO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS (Ginebra, 23 a 27 de junio de 2008) Relator: Olivier de Schutter Resumen La 15ª reunión anual de los procedimientos especiales se celebró en Ginebra del 23 al 27 de junio de 2008. Los participantes eligieron a Asma Jahangir Presidenta de la 15ª reunión anual y del Comité de Coordinación. Olivier de Schutter fue elegido Relator de la reunión y miembro del Comité de Coordinación. Cephas Lumina, María Magdalena Sepúlveda y Gulnara Shahinian fueron elegidos miembros del Comité de Coordinación. La anterior Presidenta, Gay McDougall, será miembro de oficio. Los titulares de mandatos intercambiaron opiniones con la Alta Comisionada Adjunta, el anterior Presidente del Consejo de Derechos Humanos, el Presidente del Consejo y los miembros de la Mesa del Consejo. -

Protection of Human Rights

Chapter II Protection of human rights In 2014, the United Nations remained engaged in water and sanitation, health, adequate housing, protecting human rights through its main organs— education and a life free from poverty. the General Assembly, the Security Council and the In other developments, the Permanent Memorial Economic and Social Council—and the Human Committee entered into an agreement with an archi- Rights Council, which carried out its task as the tect for the construction of a permanent memorial at central UN intergovernmental body responsible for UN Headquarters in honour of the victims of slavery promoting and protecting human rights and funda- and the transatlantic slave trade, to be completed in mental freedoms worldwide. The Council addressed 2015. In September, the first World Conference on violations, worked to prevent abuses, provided overall Indigenous People, convened as a high-level meeting policy guidance, monitored the observance of human of the General Assembly, adopted an action-oriented rights around the world and assisted States in fulfilling document on the realization of indigenous rights. their human rights obligations. The special procedures mandate holders—special rapporteurs, independent experts, working groups Special procedures and representatives of the Secretary-General—moni- tored, examined, advised and publicly reported on Report of High Commissioner. In her annual human rights situations in specific countries or on report to the Human Rights Council [A/HRC/28/3], major human rights violations worldwide. At the end the United Nations High Commissioner for Human of 2014, there were 53 special procedures (39 thematic Rights, Navanethem Pillay, noted that the expertise of mandates and 14 country- or territory-related man- special procedures helped to draw attention to emerg- dates) with 77 mandate holders. -

Asamblea General Distr

Naciones Unidas A/HRC/22/1 Asamblea General Distr. general 26 de diciembre de 2012 Español Original: inglés Consejo de Derechos Humanos 22º período de sesiones Tema 1 de la agenda Cuestiones de organización y de procedimiento Anotaciones a la agenda del 22º período de sesiones del Consejo de Derechos Humanos Nota del Secretario General GE.12-19012 (S) 150113 160113 A/HRC/22/1 Índice Párrafos Página 1. Cuestiones de organización y de procedimiento ..................................................... 1–10 3 2. Informe anual del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos e informes de la Oficina del Alto Comisionado y del Secretario General.................................................................................................................... 11–38 4 3. Promoción y protección de todos los derechos humanos, civiles, políticos, económicos, sociales y culturales, incluido el derecho al desarrollo ...................... 39–67 10 A. Derechos económicos, sociales y culturales................................................... 39–43 10 B. Derechos civiles y políticos............................................................................ 44–49 11 C. Derechos de los pueblos, y grupos e individuos específicos .......................... 50–59 12 D. Interrelación de los derechos humanos y cuestiones temáticas de derechos humanos.......................................................................................................... 60–67 13 4. Situaciones de derechos humanos que requieren la atención del Consejo -

Berichterstatter Des HRC VN 5-08.Qxp

Übersichten | Berichterstatter des Menschenrechtsrats Berichterstatter, Experten, Beauftragte und Arbeitsgruppen des Menschenrechtsrats (Stand: 1. Oktober 2008) Thematische Mandate (26) seit derzeit Unabhängige Expertin für die Fragen der Menschenrechte und extremer Armut 1998 Maria Magdalena Sepulveda, Chile Sonderberichterstatter über das Recht auf Bildung 1998 Vernor Muñoz Villalobos, Costa Rica Beauftragter des Generalsekretärs für Binnenvertriebene 2004 Walter Kälin, Schweiz Sonderberichterstatter über Folter und andere grausame, unmenschliche oder erniedrigende 1985 Manfred Nowak, Österreich Behandlung oder Strafe Sonderberichterstatterin über Gewalt gegen Frauen, deren Ursachen und deren Folgen 1994 Yakin Ertürk, Türkei Sonderberichterstatter über die nachteiligen Auswirkungen der illegalen Verbringung und 1995 Okechukwu Ibeanu, Nigeria Ablagerung toxischer und gefährlicher Stoffe und Abfälle auf den Genuss der Menschenrechte Sonderberichterstatter über das Recht eines jeden auf das für ihn erreichbare Höchstmaß an 2002 Paul Hunt, Neuseeland körperlicher und geistiger Gesundheit Sonderberichterstatter über außergerichtliche, summarische oder willkürliche Hinrichtungen 1982 Philip Alston, Australien Sonderberichterstatter über die Situation der Menschenrechte und Grundfreiheiten der 2001 James Anaya, Vereinigte Staaten Angehörigen indigener Bevölkerungsgruppen Sonderberichterstatterin über den Verkauf von Kindern, die Kinderprostitution und die Kinder- 1990 Najat M’jid Maala, Marokko pornografie Sonderberichterstatter über die Förderung