Swami Bhaktipada, Ex-Hare Krishna Leader, Dies at 74

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAM Volume 3 Issue 1 Cover and Front Matter

jsam cover_January.qxd 1/9/09 12:02 AM Page 1 JOURNAL OF THE JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN MUSIC VOLUME 3 • NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2009 JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN MUSIC SOCIETY FOR TABLE OF CONTENTS AMERICAN MUSIC VOLUME 3 Ⅲ NUMBER 1 Ⅲ FEBRUARY 2009 Continued on inside back cover Cambridge Journals online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/sam Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.8, on 02 Oct 2021 at 00:05:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196309090075 jsam cover_January.qxd 1/9/09 12:02 AM Page 2 Continued from back cover Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.8, on 02 Oct 2021 at 00:05:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196309090075 Journal of the Society for American Music A quarterly publication of the Society for American Music Editor Leta E. Miller (University of California, Santa Cruz, USA) Assistant Editor Mark Davidson (University of California, Santa Cruz, USA) Book Review Editor Amy C. Beal (University of California, Santa Cruz, USA) Recording Review Editor Daniel Goldmark (Case Western Reserve University, USA) Multimedia Review Editor Jason Stanyek (New York University, USA) Editorial Board David Bernstein (Mills College, USA) Jose´ Bowen (Southern Methodist University, USA) Martin Brody (Wellesley -

Killing for Krishna

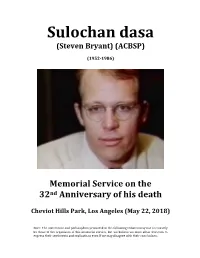

Sulochan dasa (Steven Bryant) (ACBSP) (1952-1986) Memorial Service on the 32nd Anniversary of his death Cheviot Hills Park, Los Angeles (May 22, 2018) Note: The statements and philosophies promoted in the following tributes may not necessarily be those of the organizers of this memorial service, but we believe we must allow devotees to express their sentiments and realizations even if we may disagree with their conclusions. TRIBUTES Henry Doktorski, author of Killing For Krishna. My dear assembled Vaishnavas: Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada. My name is Henry Doktorski; I am a former resident of New Vrindaban and a former disciple of Kirtanananda Swami. Some of my friends know me by my initiated name: Hrishikesh dasa. I am the author of a book—Killing For Krishna: The Danger of Deranged Devotion—which recounts the unfortunate events which preceded Sulochan’s murder, the murder itself, and its aftermath and repercussions. Prabhus and Matajis, thank you for attending this memorial service for Sulochan prabhu, the first of many anticipated annual events for the future. Although Sulochan was far from a shining example of a model devotee, and he was unfortunately afflicted with many faults, he should nonetheless, in my opinion, be respected and honored for (1) his love for his spiritual master, and (2) his courageous effort to expose corruption within his spiritual master’s society. His endeavors to (1) expose the so-called ISKCON spiritual masters of his time as pretenders, by writing and distributing his hard-hitting and mostly-accurate book, The Guru Business, and (2) dethrone the zonal acharyas, with violence if necessary, resulted in a murder conspiracy spearheaded by two ISKCON gurus, several ISKCON temple presidents and several ksatriya hit men from ISKCON temples in West Virginia, Ohio and Southern California. -

“This Is My Heart” Patita Uddharana Dasa, Editor / Compiler

“This Is My Heart” Patita Uddharana dasa, Editor / Compiler “This Is My Heart” Remembrances of ISKCON Press …and other relevant stories Manhattan / Boston / Brooklyn 1968-1971 1 Essays by the Assembled Devotees “This Is My Heart” Remembrances of ISKCON Press …and other relevant stories Manhattan / Boston / Brooklyn 1968-1971 Patita Uddharana Dasa Vaishnava Astrologer and Author of: 2 -The Bhrigu Project (5 volumes) (with Abhaya Mudra Dasi), -Shri Chanakya-niti with extensive Commentary, -Motorcycle Yoga (Royal Enflied Books) (as Miles Davis), -What Is Your Rashi? (Sagar Publications Delhi) (as Miles Davis), -This Is My Heart (Archives free download) (Editor / Compiler), -Shri Pushpanjali –A Triumph over Impersonalism -Vraja Mandala Darshan – Touring the Land of Krishna -Horoscope for Disaster (ms.) -Bharata Darshan (ms.) ―I am very pleased also to note your appreciation for our Bhagavad-gita As It Is, and I want that all of my students will understand this book very nicely. This will be a great asset to our preaching activities.‖ (-Shrila Prabhupada, letter to Patita Uddharana, 31 May 1969) For my eternal companion in devotional service to Shri Guru and Gauranga Shrimati Abhaya Mudra Devi Dasi A veritable representative of Goddess Lakshmi in Krishna’s service without whose help this book would not have been possible ―We are supposed to take our husband or our wife as our eternal companion or assistant in Krishna conscious service, and there is promise never to separate.‖ (Shrila Prabhupada, letter 4 January 1973) (Shri Narada tells King Yudhishthira:) ―The woman who engages in the service of her 3 husband, following strictly in the footsteps of the goddess of fortune, surely returns home, back to Godhead, with her devotee husband, and lives very happily in the Vaikuṇṭha planets.‖ “Shrila Prabhupada” by Abhaya Mudra Dasi “Offer my blessings to all the workers of ISKCON Press because that is my life.” (-Shrila Prabhupada, letter 19 December 1970) 4 Table of Contents Introduction ―Books Any Man Would Be Proud to Have‖ ……... -

@ 1975: GBC RESOLUTIONS, March 1975

@ 1975: GBC RESOLUTIONS, March 1975 http://www.dandavats.com/wp-content/uploads/GBCresol... @ 1975: GBC RESOLUTIONS, March 1975 1) Jayatirtha presented a definition of GBC, which was accepted as follows: Resolved: The GBC (Governing Body Commissioned) has been established by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada to represent Him in carrying out the responsibility of managing the International Society for Krishna Consciousness of which He is the Founder-Acarya and supreme authority. The GBC accepts as its life and soul His divine instructions and recognizes that it is completely dependent on His mercy in all respects. The GBC has no other function or purpose other than to execute the instructions so kindly given by His Divine Grace and preserve and spread his Teachings to the world in their pure form. It is understood that the GBC, as a collective body of 14-members has been authorized by His Divine Grace to make necessary arrangements for carrying out these responsibilities of management. These arrangements may include delegating authority, managing resources, setting objectives, making plans, calling for reports, evaluating results, training others, maintaining spiritual standards and defining sphere of influence of the various GBC members as well as other devotees. The members of the GBC do not have any inherent authority but rather derive their authority from the Governing Body Commission itself and ultimately from His Divine Grace. Their authority may be over a particular geographic area or over a particular function. Whichever area of responsibility be given to the various members their primary responsibility is to the society as a whole. -

The Bulletin O F T H E S O C I E T Y F O R a M E R I C a N M U S I C F O U N D E D I N H O N O R O F O S C a R G

The Bulletin OF THE S OCIETY FOR A MERIC A N M U S IC FOUNDED IN HONOR OF O S C A R G . T. S ONNECK Vol. XXXV, No. 1 Winter 2009 Denver Update tations and performances covering the night events: the traditional SAM Sacred entire historical, ethnic, geographic, and Harp Sing and the induction of the 2009 stylistic range of American music. We are honorary member Tony Isaacs, founder particularly glad to note that the main and chief recordist of Indian House Re- themes of the conference—Native Ameri- cords, which will follow the sing. Isaacs can music and music in the West—are has recorded the music of Native Ameri- very well represented on the program. No can singers and drummers for over forty fewer than seven sessions will be devoted years, and Indian House has one of the to Native American/First Nations/Indig- largest catalogues of recorded native mu- enous musical traditions of the United sic making available commercially. He will States, Canada, and Mexico, surely a first present a lecture on the Plains music of for SAM. And sessions devoted to topics the powwow, illustrated with live perfor- as wide-ranging as Canadian compos- mances by a prominent Colorado drum ers, Cage and Sousa, popular music in and singing group. On Friday after lunch, Los Angeles, music in Colorado and the Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy band, featuring Pacific Northwest, Julius Eastman and performers from Wyoming and Montana, experimental music in New York City, will present a visually illustrated and nar- 18th- and 19th-century repertories, film rated concert of the music of Buffalo Bill’s music, and musical theater also appear on outdoor traveling Wild West Show, which the program. -

Lotuses in Muddy Water: Fracked Gas and the Hare Krishnas at New Vrindaban, West Virginia

Lotuses in Muddy Water: Fracked Gas and the Hare Krishnas at New Vrindaban, West Virginia Kevin Stewart Rose American Quarterly, Volume 72, Number 3, September 2020, pp. 749-769 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2020.0043 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/765831 [ Access provided at 6 Jul 2021 14:51 GMT from University of Virginia Libraries & (Viva) ] Fracked Gas and the Hare Krishnas at New Vrindaban, West Virginia | 749 Lotuses in Muddy Water: Fracked Gas and the Hare Krishnas at New Vrindaban, West Virginia Kevin Stewart Rose ach morning before the sun rises, devotees of the International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in New Vrindaban gather in a Edimly lit temple to chant the mahamantra to Krishna. As the residents of this remote religious commune in West Virginia’s northern panhandle chant in unison, their voices rising and falling over the hourlong service, robed worshippers offer a series of objects to an image of Krishna to stir up their lord’s love for the Earth. The flame of a ghee lamp is waved before the image, offering Krishna the pleasure of warmth and light produced from the milk of the community’s sacred cows. Then the lamps are carried to each of the devotees, who, one by one, briefly hold their hands over the flame before placing them on their heads, transferring the warmth of the lamp to their own bodies. Next, a pink flower is held up to Krishna before again being carried to the devotees. -

Srila Prabhupada His Movement And

Dedication Dedicated to my spiritual master, His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Acharya of the Brahma-Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya, Founder- Acharya of the Hare Krishna Movement. “He lives forever by his divine instructions, and the follower lives with him.” mukam karoti vachalam pangum langhayate girim yat-kripa tam aham vande sri gurum dina tarinam “By the mercy of the Guru even a dumb man can become a great speaker, and even a lame man can cross mountains.” “All my disciples will take the legacy. If you want, you can also take it. Sacrifice everything. I, one, may soon pass away. But they are hundreds, and this movement will increase. It is not that I give an order, ‘Here is the next leader.’ Anyone who follows the previous leadership is the leader…. All of my disciples are leaders, as much as they follow purely. If you want to follow, you can also lead. But you don’t want to follow. Leader means one who is a first class disciple. Evam parampara praptam. One who is following is perfect.” (Srila Prabhupada, Back to Godhead magazine, Vol. 13, No. 1-2) Phalgun Krishna Panchami By His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada The following is an offering of five prayers glorifying special characteristics of Srila 108 Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Goswami Thakur. Presented on the commemoration of his appearance at the Radha-Damodara temple, Vrindavan, India in 1961. First Vasistya 1. On this day, O my master, I made a cry of grief; I was not able to tolerate the absence of my guru. -

1979 Page 1 of 6 1979 06/10/2017

1979 Page 1 of 6 Home Srila Prabhupada ISKCON GBC Ministries Strategic Planning ILS News Resources Multimedia Contact 1979 FEBRUARY 3, 2012 GBC RESOLUTIONS 1979. MARCH 1,1979. Officers of the GBC for 1979 are: Chairman : Jayatirtha Goswami. Vice Chairman : Hridayananda Goswami. Secretary : Adi Kesava Swami. MARCH 5,1979. 1. Review of old business. 1. Resolved: That all standing commitee must submit a written report to the chairman of the GBC before the beginning of the committee meeting proceeding the annual GBC meeting at Mayapur. 2.Resolved: That the names of Bali Mardan and Guru Kripa Swami be dropped from the list of GBC members. 3. Resolved: That the Bhakktivedanta Memorial Committee, constituted at the annual meeting on March 18, 1978 review the situation of the purchase of 26 Second Ave.,NY (Srila Prabhupadas original temple) and make a report to the full body, including discussion of other activities of the committee during the last year. 4. Resolved: That Satsvarupa Maharaja will submit a written report on the progress of the biography of Srila Prabhupada’s life sometime shortly after Gaura-Purnima. 5. Resolved: That the March 21,1978 GBC resolution No.18 reading: “All children’s books produced by ISKCON or affiliates or subsidiaries must have approval of the Minister of Education” is amended to read,”All chilldren’s books,including coloring books produced by ISKCON or affiliates or subsidiaries must have approval of the Minister of Education”. 6. Resolved: That the No.19 or March 21,1978 may be deleted, as it is obsolete. 7. Resolved: That resolution No.of the March 21,1978 GBC annual meeting may be deleted. -

Post 1977 Iskcon Initiating Gurus

POST 1977 ISKCON INITIATING GURUS FALLDOWNS, CENSURES, RETIREMENTS, ETC FROM THE ORIGINAL 11 ZONAL ACARYA ‘GURUS’ WHO CLAIMED THEY WERE APPOINTED BY PRABHUPADA, BUT LATER ALL ADMITTED THEY WERE NOT APPOINTED, FAILING TO EXPLAIN HOW THEY BECAME AND CONTINUED AS DIKSA GURUS: 1. Bhagavan Das Goswami: married a disciple, abdicated 2. Bhavananda Goswami: expelled due to homosexual activity 3. Harikesa Swami: married his massage therapist, abdicated 4. Hansadutta Swami: fell down 1981‐3, excommunicated, became a rtvik reformer 5. Hrdayananda Goswami: retired from active service, seen with women disciples, now incognito 6. Jayatirtha Das: claimed LSD was a sacrament, decapitated by disciple 7. Kirtanananda Swami: homosexual relations with children, 8 years in prison, now deceased 8. Ramesvara Swami: caught at mall with teenage girls, returned to family, married, doing business 9. Satsvarupa Das Goswami: relations with another devotee’s wife but refused to give up sannyas 10. Tamal Krishna Goswami: GBC ordered him to suspend initiations in 1980 due to his claiming to be the sole authorized ISKCON guru, after which he explained that Prabhupada never appointed gurus but only appointed rtviks. Immediately GBC re‐instated him. GBC chastised and restricted him in 1996 for his involvement and promotion of Narayan Maharaj as the next ISKCON acharya. Now deceased. His PhD thesis in 2002 was about how Prabhupada had begun a new religion. Deceased March 2002. IN 1984‐1987, GBC MODIFIED ISKCON’S GURU SYSTEM, FINALLY ALLOWING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ANY DEVOTEE WITH 5 YEARS GOOD STANDING AND WITH A NO OBJECTION VOTE AUTHORUIZATION TO ACCEPT DISCIPLES (AT THEIR OWN RISK). -

![TRANSCRIPT Intro [Sound of Child at Zoo: “Wake Up, Lion!”; Lion Roar]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8959/transcript-intro-sound-of-child-at-zoo-wake-up-lion-lion-roar-2728959.webp)

TRANSCRIPT Intro [Sound of Child at Zoo: “Wake Up, Lion!”; Lion Roar]

From Cages to Conservation - American Zoos: Inside Out TRANSCRIPT Intro [sound of child at zoo: “Wake up, lion!”; lion roar] RUSSO: The zoo is one of America’s most popular institutions. Millions pass through its gates every year. And the best zoos say they’re more than a good time. BOYLE: As we urbanize more and more, as we lose species, zoos are playing a very important role in connecting people to nature. RUSSO: I’m Christina Russo, and this is “From Cages to Conservation—American Zoos: Inside Out.” Top zoos say they provide great animal care, are big conservationists and inspire visitors to save wildlife. But critics aren’t buying it. FARINATO: All it means is you’ve got a bunch of people going through the gate, looking at what you put in front of them, and walking out the gate. RUSSO: In the next hour: just who are zoos serving—the public, the animals or themselves? “From Cages to Conservation—American Zoos: Inside Out” is next. First, this news. Part I RUSSO: This is a special report from WBUR Boston. “From Cages to Conservation— American Zoos: Inside Out.” I’m Christina Russo. [Oakland zoo carousel ambience; children and calliope music] RUSSO: Going to the zoo—it's one of America’s favorite pastimes: peanuts, a merry-go- round, and some Sunday afternoon family fun with the animals. [Oakland zoo carousel ambience; children and calliope music cont’d] RUSSO: There are 2700 zoos and other animal exhibitors across the country. They range from tiny ramshackle attractions to modern facilities hundreds of acres in size. -

The Struggle for Truth by the Devotees of Iskcon-Bangalore Following the Acharya's Directions

Krishna Voice Supplement March 2009 Calling upon the gracious support of Life Patrons & Donors of ISKCON-Bangalore THE STRUGGLE FOR TRUTH BY THE DEVOTEES OF ISKCON-BANGALORE FOLLOWING THE ACHARYA'S DIRECTIONS The pains of this struggle for truth have been borne silently by the devotees of ISKCON-Bangalore for the last nine years. So far we have been trying our best to contain this within the institution. However, it has become necessary today, unfortunately, to disseminate the sensitive information of purely internal nature in this paper. Our adversaries are exploiting our silence by perpetrating false and maligning propaganda against the devotees of ISKCON-Bangalore, even more vigorously than ever before, in order to demean our cause, and sidestep the real issue. As supporters and donors of this organization, we believe it is your right to be informed by us of the real issues that have transpired in this matter. In this second issue, we present more details concerning the developments in ISKCON post 1977. (For internal circulation) In 1965, at the age of seventy, Sri Srimad A.C. too taught this principle. In one of the Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prabhupada set out Bhaktivedanta purports he quotes a verse from on a 35-day long trans-Atlantic voyage to the Upanishad: US, carrying with him Rs.40 and a trunk load of The entire Vedic program is based on this his English translations of the Srimad principle, and one can understand it as Bhagavatam. He had carried in his heart for over recommended in the Vedas: four decades, the order of his spiritual master to spread the message of Bhagavad-gita and other yasya deve parä bhaktir Vedic literatures all over the world. -

American Guild of Organists Chapter Deans American Guild of Organists

American Guild of Organists Chapter Deans 07/10/2020 Alabama Birmingham Chapter (C401) Dothan-Wiregrass Chapter (C456) East Alabama Chapter (C458) Ms. Sherelyn Breland Mr. Edward Montgomery, BMus Mr. Rigney Cofield 229 Oak Forest Dr. 109 N. Bell St. 219 30th Street Pelham, AL 35124 Dothan, AL 36303 Opelika, AL 36801-6117 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Home Phone: 205-664-1373 Home Phone: 334-794-5763 Work Phone: 334-887-3901 Home Phone: 334-704-7456 http://www.birminghamago.org/ Greater Huntsville Chapter (C402) Mobile Chapter (C403) Montgomery Chapter (C404) Mr. Stephen Sivley Dr. Randall C. Sheets, DMA Mr. Raymond Johnson, SPC, JD 326 River Rock dr 10 Westminster Way 640 S. McDonough St. Madison, AL 35756 Mobile, AL 36608 Montgomery, AL 36104 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Home Phone: 256-476-2106 Work Phone: 251-342-1550 Work Phone: 334-265-8731 Home Phone: 251-414-3510 Home Phone: 334-281-2795 Fax: 334-832-1051 http://huntsvilleago.org/web/ https://www.agohq.org/chapters/mobile Arizona Central Arizona Chapter (C901) Southern Arizona Chapter (C903) Mr. Gary E. Quamme, MM Ms. Janet P. Tolman, BMus 8122 W Acoma Drive 5266 N. Tigua Dr. Peoria, AZ 85381 Tucson, AZ 85704-3740 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Home Phone: 480-788-3522 Work Phone: 520-327-1116 Home Phone: 520-888-3173 http://www.cazago.org http://www.agosaz.com Arkansas Central Arkansas Chapter (C701) Fort Smith Chapter (C702) Northwest Arkansas Chapter (C703) Mr.