New Vrindaban: Pilgrimage, Patronage, and Demographic Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Introduction: Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal

chapter 1 Introduction : Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal-Vaishnavism background The anthropology of Hinduism has amply established that Hindus have a strong involvement with sacred geography. The Hindu sacred topography is dotted with innumerable pilgrimage places, and popu- lar Hinduism is abundant with spatial imaginings. Thus, Shiva and his partner, the mother goddess, live in the Himalayas; goddesses descend to earth as beautiful rivers; the goddess Kali’s body parts are imagined to have fallen in various sites of Hindu geography, sanctifying them as sacred centers; and yogis meditate in forests. Bengal similarly has a thriving culture of exalting sacred centers and pilgrimage places, one of the most important being the Navadvip-Mayapur sacred complex, Bengal’s greatest site of guru-centered Vaishnavite pilgrimage and devo- tional life. While one would ordinarily associate Hindu pilgrimage cen- ters with a single place, for instance, Ayodhya, Vrindavan, or Banaras, and while the anthropology of South Asian pilgrimage has largely been single-place-centered, Navadvip and Mayapur, situated on opposite banks of the river Ganga in the Nadia District of West Bengal, are both famous as the birthplace(s) of the medieval saint, Chaitanya (1486– 1533), who popularized Vaishnavism on the greatest scale in eastern India, and are thus of massive simultaneous importance to pilgrims in contemporary Bengal. For devotees, the medieval town of Navadvip represents a Vaishnava place of antique pilgrimage crammed with cen- turies-old temples and ashrams, and Mayapur, a small village rapidly 1 2 | Chapter 1 developed since the nineteenth century, contrarily represents the glossy headquarters site of ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), India’s most famous globalized, high-profile, modern- ized guru movement. -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

The Ratha Yatra of Sri Jagannath

Srimandira The Ratha Yatra of Shri Jagannath l Jayanta Narayan Panda Orissa the Land of festivals is known Green timbers respectively. Beside the D.F.O. Nayagarh have been supplying 3 world-wide during the monsoon for the Nos. of Simuli timbers for last some years. spectacular festival, Ratha Yatra or the Now a days the availability of Fasi species Car Festival of Shri Jagannath. Among of trees has become a problem in twelve major festivals, viz. the Snana Nayagarh Division, as a result of which Yatra, the Ratha Yatra, the Sayan Yatra, the D.F.O. Nayagarh has to procure the the Dakshinayana Yatra, the Fasi trees from other Divisions to supply Parswaparivartan Yatra, the Utthapana the same to the Temple Administration. Yatra, the Pravarana Yatra, the Like previous years the D.F.O. Nayagarh Pusyabhisheka Yatra, the Uttarayana sends first truck load of timber before Yatra, the Dola Yatra, the Damanaka Yatra 'Basanta Panchami' and the rest of the and the Akshaya Trutiya Yatra are timbers reaches in a phased manner. celebrated inside the temple of Lord Jagannath ; The Ratha Yatra or the Car The construction of the Rathas starts Festival of Lord deserves special mention. on the Akshaya Trutiya day. The progress This festival draws millions of tourists both of construction is monitored regularly by in-land and foreigners to the Grand Road. a team of officials. The Executive And the deities come down from the main Engineer, R & B, Puri Division, Puri is temple to the Grand Road to meet the reviewing the progress from time to time. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Calendar of Religious Festivals January to June

shap Calendar of Religious Festivals EDUCATION and 2020 CELEBRATION January to June FAITHS January February March April May June 23 Declaration of 20 to1 May the Bab 19 World Religion Day 20 Naw-Ruz BAHA’I Ridvan 28 The Ascension of Baha’u’llah 16 Shinran Mem. Day 8/15 Parinirvana / 8 Hanamatsuri 7 Vesakha Puja / BUDDHIST 25 Honen Mem. Day Nirvana Day 25-27 Losar 9 Magha Puja* 13-15 Songkran Buddha Day 25 Yuan Tuan 4 Tomb 25 Dragon Boat CHINESE (New Year)[Rat] 8 Lantern Festival Sweeping Day Festival 1 Naming of Jesus / 2 Great Lenten Fast Circumcision / Mary, 10-16 Christian Aid Mother of God begins [3] 5 Palm Sunday 7 Trinity Sunday 2 Presentation of 6 Women s World Week 5-12 Methodist Covenant ’ 5-11 Holy Week 21 Ascension Day 7 Pentecost [3] Christ in the 9 Maundy 11 Thanksgiving 6 Epiphany [Ang/RC] Temple / Day of Prayer 21 Ascension Day 6 Theophany [3] 19 St Joseph Thursday for the CHRISTIAN Candlemas [RC] 6/7 Christmas Eve/Day [3] 22 Mothering Sunday 10 Good Friday 28 Ascension Day Eucharist 25 Shrove Tuesday 11 Holy Saturday 11 Corpus Christi - 12 Baptism of Christ [Ang] 26 Ash Wednesday 25 The Annunciation [3] 12 Baptism of the Lord [RC] [Ang/[3]/RC] 12 Easter Day Body & Blood 26 - April 11 Lent 31 Pentecost / 18-25 Week of Prayer for 25 Lady Day 19 Pascha [3] Whit Sunday of Christ [RC] Christian Unity 29 Passion Sunday 19 Theophany [3] (Julian) 12 B’day of Swami Vivekananda 2 Rama Navami 14/15 Lohri / Makar HINDU 21 Mahashivratri 9/10 Holi 7/8 Hanuman 23 Ratha Yatra Sankranti / Pongal Jayanti *29/30 Sarasvati Puja / Vasant Panchami -

Hinduism Around the World

Hinduism Around the World Numbering approximately 1 billion in global followers, Hinduism is the third-largest religion in the world. Though more than 90 percent of Hindus live on the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan), the Hindu diaspora’s impact can still be felt today. Hindus live on every continent, and there are three Hindu majority countries in the world: India, Nepal, and Mauritius. Hindu Diaspora Over Centuries Hinduism began in the Indian subcontinent and gradually spread east to what is now contemporary Southeast Asia. Ancient Hindu cultures thrived as far as Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Some of the architectural works (including the famous Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia) still remain as vestiges of Hindu contact. Hinduism in Southeast Asia co-worshipped with Buddhism for centuries. However, over time, Buddhism (and later Islam in countries such as Indonesia) gradually grew more prominent. By the 10th century, the practice of Hinduism in the region had waned, though its influence continued to be strong. To date, Southeast Asia has the two highest populations of native, non-Indic Hindus: the Balinese Hindus of Indonesia and the Cham people of Vietnam. The next major migration took place during the Colonial Period, when Hindus were often taken as indentured laborers to British and Dutch colonies. As a result, Hinduism spread to the West Indies, Fiji, Copyright 2014 Hindu American Foundation Malaysia, Mauritius, and South Africa, where Hindus had to adjust to local ways of life. Though the Hindu populations in many of these places declined over time, countries such as Guyana, Mauritius, and Trinidad & Tobago, still have significant Hindu populations. -

SAM Volume 3 Issue 1 Cover and Front Matter

jsam cover_January.qxd 1/9/09 12:02 AM Page 1 JOURNAL OF THE JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN MUSIC VOLUME 3 • NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2009 JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN MUSIC SOCIETY FOR TABLE OF CONTENTS AMERICAN MUSIC VOLUME 3 Ⅲ NUMBER 1 Ⅲ FEBRUARY 2009 Continued on inside back cover Cambridge Journals online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/sam Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.8, on 02 Oct 2021 at 00:05:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196309090075 jsam cover_January.qxd 1/9/09 12:02 AM Page 2 Continued from back cover Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.8, on 02 Oct 2021 at 00:05:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196309090075 Journal of the Society for American Music A quarterly publication of the Society for American Music Editor Leta E. Miller (University of California, Santa Cruz, USA) Assistant Editor Mark Davidson (University of California, Santa Cruz, USA) Book Review Editor Amy C. Beal (University of California, Santa Cruz, USA) Recording Review Editor Daniel Goldmark (Case Western Reserve University, USA) Multimedia Review Editor Jason Stanyek (New York University, USA) Editorial Board David Bernstein (Mills College, USA) Jose´ Bowen (Southern Methodist University, USA) Martin Brody (Wellesley -

In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a Guide to the Temples, Beliefs and People of Tamil Nadu

* In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a guide to the temples, beliefs and people of Tamil Nadu The South India Saiva Siddhantha Works Publishing Society, Tinnevelly, Ltd, Madras, 1993. I.S.B.N.: 0-9661496-2-9 Copyright © 1993 Chantal Boulanger. All rights reserved. This book is in shareware. You may read it or print it for your personal use if you pay the contribution. This document may not be included in any for-profit compilation or bundled with any other for-profit package, except with prior written consent from the author, Chantal Boulanger. This document may be distributed freely on on-line services and by users groups, except where noted above, provided it is distributed unmodified. Except for what is specified above, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system - except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper - without permission in writing from the author. It may not be sold for profit or included with other software, products, publications, or services which are sold for profit without the permission of the author. You expressly acknowledge and agree that use of this document is at your exclusive risk. It is provided “AS IS” and without any warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. If you wish to include this book on a CD-ROM as part of a freeware/shareware collection, Web browser or book, I ask that you send me a complimentary copy of the product to my address. -

Chaitanya-Charitamrita Compact

Chaitanya-Charitamrita Compact A summary study of Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’s life story By Sutapa das Based on Shri Chaitanya-Charitamrita translated by His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Founder Acharya: International Society for Krishna Consciousness O devotees, relish daily the nectar of Shri Chaitanya-Charitamrita and the pastimes of Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, for by doing so one can merge in transcendental bliss and attain full knowledge of devotional service. (Antya-Lila 5.89) © 2015, Bhaktivedanta Manor Text: Sutapa Das Design & Graphics: Prasannatma Das Layout: Yogendra Sahu Artwork courtesy of The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. www.krishna.com. The International Society for Krishna Consciousness Founder Acarya: His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada College of Vedic Studies Bhaktivedanta Manor, Hilfield Lane, Watford, WD25 8EZ 01923 851000 www.krishnatemple.com [email protected] Dedicated to: Shrila Krishnadasa Kaviraja Goswami, who, being requested by the Vaishnava community, was divinely empowered to compose this spotless biography. A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who carried the message of Shri Chaitanya to the Western world, established the ISKCON movement, and kindly translated this priceless literature into English. Kadamba Kanana Swami, who nurtured my interest in Chaitanya-Charitamrita, and provides ongoing inspiration and guidance in my spiritual journey. Contents Introduction ..........................................................................7 The God -

8. Krishna Karnamrutam

Sincere Thanks To: 1. SrI nrusimha SEva rasikan, Oppiliappan Koil V.SaThakOpan swAmi, Editor- In-Chief of sundarasimham-ahobilavalli kaimkaryam for kindly editing and hosting this title in his eBooks series. 2. Mannargudi Sri.Srinivasan NarayaNan swami for compilation of the source document and providing Sanskrit/Tamil Texts and proof reading 3. The website http://www.vishvarupa.com for providing the cover picture of Sri GuruvAyUrappan 4. Nedumtheru Sri.Mukund Srinivasan,Sri.Lakshminarasimhan Sridhar, www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org Smt.Krishnapriya for providing images. 5. Smt.Krishnapriya for providing the biography of Sri Leela Sukhar for the appendix section and 6. Smt. Jayashree Muralidharan for eBook assembly C O N T E N T S Introduction 1 Slokams and Commentaries 3 Slokam 1 -10 5-25 Slokam 11 - 20 26-44 Slokam 21 - 30 47-67 Slokam 31 - 40 69-84 www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org Slokam 41 - 50 86-101 Slokam 51 - 60 103-119 Slokam 61 - 70 121-137 Slokam 71 - 80 141-153 Slokam 81 - 90 154-169 Slokam 91 - 100 170-183 Slokam 101 - 110 184-201 nigamanam 201 Appendix 203 Brief Biography of Sri Leelaa Sukhar 205 Complete List of Sundarasimham-ahobilavalli eBooks 207 www.sadagopan.org www.sadagopan.org SrI GuruvAyUrappan . ïI>. ïIlIlazukkiv ivrictm! . ïIk«:[k[aRm&tm!. KRISHNAAKARNAAMRTAM OF LEELASUKA X×W www.sadagopan.org ABOUT THE AUTHOR The name of the author of this slokam is Bilavamangala and he acquired the name Leelasuka because of his becoming immersed in the leela of KrishNa and describing it in detail like Sukabrahmarshi. -

Killing for Krishna

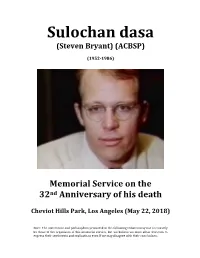

Sulochan dasa (Steven Bryant) (ACBSP) (1952-1986) Memorial Service on the 32nd Anniversary of his death Cheviot Hills Park, Los Angeles (May 22, 2018) Note: The statements and philosophies promoted in the following tributes may not necessarily be those of the organizers of this memorial service, but we believe we must allow devotees to express their sentiments and realizations even if we may disagree with their conclusions. TRIBUTES Henry Doktorski, author of Killing For Krishna. My dear assembled Vaishnavas: Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada. My name is Henry Doktorski; I am a former resident of New Vrindaban and a former disciple of Kirtanananda Swami. Some of my friends know me by my initiated name: Hrishikesh dasa. I am the author of a book—Killing For Krishna: The Danger of Deranged Devotion—which recounts the unfortunate events which preceded Sulochan’s murder, the murder itself, and its aftermath and repercussions. Prabhus and Matajis, thank you for attending this memorial service for Sulochan prabhu, the first of many anticipated annual events for the future. Although Sulochan was far from a shining example of a model devotee, and he was unfortunately afflicted with many faults, he should nonetheless, in my opinion, be respected and honored for (1) his love for his spiritual master, and (2) his courageous effort to expose corruption within his spiritual master’s society. His endeavors to (1) expose the so-called ISKCON spiritual masters of his time as pretenders, by writing and distributing his hard-hitting and mostly-accurate book, The Guru Business, and (2) dethrone the zonal acharyas, with violence if necessary, resulted in a murder conspiracy spearheaded by two ISKCON gurus, several ISKCON temple presidents and several ksatriya hit men from ISKCON temples in West Virginia, Ohio and Southern California. -

Mayapur Katha’

BY BHAGAVATAM RIITA DAS: CASTING OF THE PANCHA-TATTVA DEITIES read p.3 - 6 NEED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF COMMUNITY BUSINESSES read p. 20 - 21, 24 PIONEER ‘Everyone is talking about OW ROTECTION varna-ashrama, but she is “COW PROTECTION” going out there and doing Read p. 19 it. She has left everyone behind’. Readp.9-12 Jaya sri krishna chaitanyaprabhunityananda sri advaita gadadhara srivasadi gaura bhakta vrinda Radha-Krishna. Radha's name is first. Why? the vaishyas are meant to protect the cows and Nobody can be better devotee than Radharani. bulls and utilize them to produce grains and milk. As soon as Radha's name is there, Krishna is The cow is meant to deliver milk, and the bull is meant more pleased. That is the way. If we glorify the to produce grains. [SB 1.17.1 Purport] devotees, the character of the devotees, before the Lord, He's more pleased than to glorify Himself, He directly. Even Krishna, Hawaii, march 24, 1969 whom we accept as the Supreme Lord, had to go to It is very encouraging that you are devel- Gurukula and oping our Mayapur center very nicely. The serve the spiritual fences are complete and now you are sowing master as a some hedge plants. Do it nicely. menial servant. I am glad to hear that you are harvesting Durban, rice. The crop may be saved to utilize for our October 10, 1975 members nicely. Regarding the bricks, it is a very good idea that you have ordered 10,000 bricks but as soon as the rainy season is Yes, we are prepared to purchase the land at a stopped we will build our temple.