T R a N S C R I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T R a N S C R I

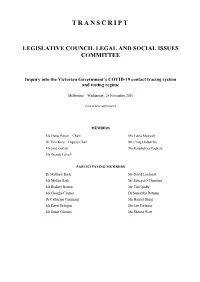

TRANSCRIPT LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL LEGAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES COMMITTEE Inquiry into the Victorian Government’s COVID-19 contact tracing system and testing regime Melbourne—Wednesday, 18 November 2020 (via videoconference) MEMBERS Ms Fiona Patten—Chair Ms Tania Maxwell Dr Tien Kieu—Deputy Chair Mr Craig Ondarchie Ms Jane Garrett Ms Kaushaliya Vaghela Ms Wendy Lovell PARTICIPATING MEMBERS Dr Matthew Bach Mr David Limbrick Ms Melina Bath Mr Edward O’Donohue Mr Rodney Barton Mr Tim Quilty Ms Georgie Crozier Dr Samantha Ratnam Dr Catherine Cumming Ms Harriet Shing Mr Enver Erdogan Mr Lee Tarlamis Mr Stuart Grimley Ms Sheena Watt Necessary corrections to be notified to executive officer of committee Wednesday, 18 November 2020 Legislative Council Legal and Social Issues Committee 1 WITNESS Dr Alan Finkel, AO, Australia’s Chief Scientist, Office of the Chief Scientist. The CHAIR: Good morning, everyone, and I would like to declare open the Standing Committee on Legal and Social Issues. It is our public hearing for the Inquiry into the Victorian Government’s COVID-19 Contact Tracing System and Testing Regime. I know it goes without saying, but please ensure that your phones are on silent—and maybe puppies as well, if that is possible. Before we get going I would like to begin this hearing by respectfully acknowledging the Aboriginal peoples, the traditional custodians of the various lands each of us are gathered on today and pay my respects to their ancestors, elders and families. And I particularly want to welcome any elders or community members who are here today to impart their knowledge on this issue to the committee or who are watching the proceedings today. -

Liberal Nationals Released a Plan

COVID-19 RESPONSE May 2020 michaelobrien.com.au COVID-19 RESPONSE Dear fellow Victorians, By working with the State and Federal Governments, we have all achieved an extraordinary outcome in supressing COVID-19 that makes Victoria – and Australia - the envy of the world. We appreciate everyone who has contributed to this achievement, especially our essential workers. You have our sincere thanks. This achievement, however, has come at a significant cost to our local economy, our community and to our way of life. With COVID-19 now apparently under a measure of control, it is urgent that the Andrews Labor Government puts in place a clear plan that enables us to take back our Michael O’Brien MP lives and rebuild our local communities. Liberal Leader Many hard lessons have been learnt from the virus outbreak; we now need to take action to deal with these shortcomings, such as our relative lack of local manufacturing capacity. The Liberals and Nationals have worked constructively during the virus pandemic to provide positive suggestions, and to hold the Andrews Government to account for its actions. In that same constructive manner we have prepared this Plan: our positive suggestions about what we believe should be the key priorities for the Government in the recovery phase. This is not a plan for the next election; Victorians can’t afford to wait that long. This is our Plan for immediate action by the Andrews Labor Government so that Victoria can rebuild from the damage done by COVID-19 to our jobs, our communities and our lives. These suggestions are necessarily bold and ambitious, because we don’t believe that business as usual is going to be enough to secure our recovery. -

Microsoft Outlook

[email protected] From: Melina Bath <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, 31 August 2020 3:49 PM To: [email protected] Subject: RE: Your vote this week Dear Bob, Thank you for taking the time to contact me regarding Andrews Labor Government’s intention to extend State of Emergency powers under the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 for an additional 12-month period. As Victoria battles COVID-19, the State of Emergency is the legal framework under which the current wide- ranging restrictions on people’s lives and livelihoods including restrictions on leaving your own home, business closures, travel bans, quarantine arrangements and curfews are made. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Andrews Labor Government has been extending the State of Emergency in four-week blocks. However, the law states that there is a maximum six-month limit, with the current declaration due to expire on 13 September 2020. This week, the Andrews Labor Government wants the Victorian Parliament to pass a new law that will extend the maximum duration of state of emergency powers from the current 6 months to a potential 18 months. The draft legislation gives effect to these proposed laws (which you can read here) – and the Liberal Nationals have many serious concerns! As well as extending the maximum duration of a state of emergency from 6 months to 18 months, under the proposed new laws: · a State of Emergency may still apply even if there are no active cases of COVID-19 in Victoria. · the Chief Health Officer can take action to eliminate a serious risk to public health if he believes it to be ‘reasonably necessary’ rather than the current ‘necessary’ which represents a much lower threshold. -

Recognising Objectors) Bill 2015

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA Environment and Planning Committee Inquiry into the Planning and Environment Amendment (Recognising Objectors) Bill 2015 Parliament of Victoria Environment and Planning Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2015 PP No 67, Session 2014-15 ISBN 978 0 9805370 8 6 (print version) 978 0 9805370 9 3 (PDF version) Contents Committee Membership iv Committee Secretariat v 1 Inquiry Process 1 2 Referral of the Bill 3 3 Provisions of the Bill 5 4 Evidence Received 7 4.1 Planning Permits 7 4.2 Background to the Planning and Environment Amendment (Recognising Objectors) Bill 2015 8 4.3 Definitional problems 10 4.4 Number of Objections 11 4.5 Not meeting the community’s expectations 13 4.6 Conclusion 14 5 Submissions 15 6 Public Hearings 17 Appendix 1 Transcripts of Evidence 19 Inquiry into the Planning and Environment Amendment (Recognising Objectors) Bill 2015 iii Committee Membership Hon David Davis MLC* Ms Harriet Shing MLC Chair Deputy Chair Southern Metropolitan Eastern Victoria Ms Melina Bath MLC Hon Richard Dalla-Riva MLC Ms Samantha Dunn MLC Eastern Victoria Eastern Metropolitan Eastern Metropolitan Mr Shaun Leane MLC Ms Gayle Tierney MLC Mr Daniel Young MLC Eastern Metropolitan Western Victoria Northern Victoria Participating Members Mr Jeff Bourman MLC Ms Colleen Hartland MLC* Mr James Purcell MLC Eastern Victoria Western Metropolitan Western Victoria * These Members participated Mr Simon Ramsay MLC* in the sub-Committee for the Western Victoria hearings on 10 July 2015. iv Environment -

Federal & State Mp Phone Numbers

FEDERAL & STATE MP PHONE NUMBERS Contact your federal and state members of parliament and ask them if they are committed to 2 years of preschool education for every child. Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Aston Alan Tudge Liberal (03) 9887 3890 Hotham Clare O’Neil Labor (03) 9545 6211 Ballarat Catherine King Labor (03) 5338 8123 Indi Catherine McGowan Independent (03) 5721 7077 Batman Ged Kearney Labor (03) 9416 8690 Isaacs Mark Dreyfus Labor (03) 9580 4651 Bendigo Lisa Chesters Labor (03) 5443 9055 Jagajaga Jennifer Macklin Labor (03) 9459 1411 Bruce Julian Hill Labor (03) 9547 1444 Kooyong Joshua Frydenberg Liberal (03) 9882 3677 Calwell Maria Vamvakinou Labor (03) 9367 5216 La Trobe Jason Wood Liberal (03) 9768 9164 Casey Anthony Smith Liberal (03) 9727 0799 Lalor Joanne Ryan Labor (03) 9742 5800 Chisholm Julia Banks Liberal (03) 9808 3188 Mallee Andrew Broad National 1300 131 620 Corangamite Sarah Henderson Liberal (03) 5243 1444 Maribyrnong William Shorten Labor (03) 9326 1300 Corio Richard Marles Labor (03) 5221 3033 McEwen Robert Mitchell Labor (03) 9333 0440 Deakin Michael Sukkar Liberal (03) 9874 1711 McMillan Russell Broadbent Liberal (03) 5623 2064 Dunkley Christopher Crewther Liberal (03) 9781 2333 Melbourne Adam Bandt Greens (03) 9417 0759 Flinders Gregory Hunt Liberal (03) 5979 3188 Melbourne Ports Michael Danby Labor (03) 9534 8126 Gellibrand Timothy Watts Labor (03) 9687 7661 Menzies Kevin Andrews Liberal (03) 9848 9900 Gippsland Darren Chester National -

Parliament of Victoria

Current Members - 23rd January 2019 Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Hon The Hon. Daniel Michael 517A Princes Highway, Noble Park, VIC, 3174 Premier Andrews MP (03) 9548 5644 Leader of the Labor Party Member for Mulgrave [email protected] Hon The Hon. James Anthony 1635 Burwood Hwy, Belgrave, VIC, 3160 Minister for Education Merlino MP (03) 9754 5401 Deputy Premier Member for Monbulk [email protected] Deputy Leader of the Labor Party Hon The Hon. Michael Anthony 313-315 Waverley Road, Malvern East, VIC, 3145 Shadow Treasurer O'Brien MP (03) 9576 1850 Shadow Minister for Small Business Member for Malvern [email protected] Leader of the Opposition Leader of the Liberal Party Hon The Hon. Peter Lindsay Walsh 496 High Street, Echuca, VIC, 3564 Shadow Minister for Agriculture MP (03) 5482 2039 Shadow Minister for Regional Victoria and Member for Murray Plains [email protected] Decentralisation Shadow Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Leader of The Nationals Deputy Leader of the Opposition Hon The Hon. Colin William Brooks PO Box 79, Bundoora, VIC Speaker of the Legislative Assembly MP Suite 1, 1320 Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC, 3083 Member for Bundoora (03) 9467 5657 [email protected] Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Mr Shaun Leo Leane MLC PO Box 4307, Knox City Centre, VIC President of the Legislative Council Member for Eastern Metropolitan Suite 3, Level 2, 420 Burwood Highway, Wantirna, VIC, 3152 (03) 9887 0255 [email protected] Ms Juliana Marie Addison MP Ground Floor, 17 Lydiard Street North, Ballarat Central, VIC, 3350 Member for Wendouree (03) 5331 1003 [email protected] Hon The Hon. -

Inquiry Into the Impact of Animal Rights Activism on Victorian Agriculture

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Economy and Infrastructure Committee Inquiry into the impact of animal rights activism on Victorian agriculture Parliament of Victoria Economy and Infrastructure Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2020 PP No 112, Session 2018-20 ISBN 978 1 925703 94 8 (print version), 978 1 925703 95 5 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Nazih Elasmar Bernie Finn Rodney Barton Northern Metropolitan Westerm Metropolitan Eastern Metropolitan Mark Gepp Bev McArthur Tim Quilty Sonja Terpstra Northern Victoria Western Victoria Northern Victoria Eastern Metropolitan Participating members Melina Bath, Eastern Victoria Dr Catherine Cumming, Western Metropolitan Hon. David Davis, Southern Metropolitan David Limbrick, South Eastern Metropolitan Andy Meddick, Western Victoria Craig Ondarchie, Northern Metropolitan Hon. Gordon Rich-Phillips, South Eastern Metropolitan Hon. Mary Wooldridge, Eastern Metropolitan ii Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee About the committee Functions The Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee’s functions are to inquire into and report on any proposal, matter or thing concerned with agriculture, commerce, infrastructure, industry, major projects, public sector finances, transport and education. As a Standing Committee, it may inquire into, hold public hearings, consider and report on any Bills or draft Bills, annual reports, estimates of expenditure or other documents laid before the Legislative Council in accordance with an Act, provided these are relevant to its functions. Secretariat Patrick O’Brien, Committee Manager Kieran Crowe, Inquiry Officer Caitlin Connally, Research Assistant Justine Donohue, Administrative Officer Contact details Address Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee Parliament of Victoria Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 8682 2869 Email [email protected] Web https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/eic-lc This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

Infant Viability Bill

MAY-JUNE 2016 Life Hike 2016 Our annual Life Hike was held in The Grampians on 26-28 May 2016 and completed by a group of keen walkers. The three day hike wove through magnificent scenery which varied from rock-climbing, walking on dirt tracks and climbing to the peak of The Pinnacles. Many of us were puffing after ascending steep staircases and Mary Collier precipitous pinches through Event Organiser the 470 metre elevation to the top! The photo is of the Mackenzie Falls - one of the features of the walk. The photographer Infant Viability Bill was at the scene just as we arrived and offered to take a long Dear Valued Supporter, exposure shot of several walkers with a professional camera. We It is with disappointment that I write to inform you that the were lucky to have our excellent guide, Eric Ward who directed us Legislative Council has voted on my Infant Viability Bill, and through the difficult terrain. has chosen to vote it down Many thanks to Dianne and David Cutler, who for the second year (with a division of 11 for, 27 provided the splendid homemade catering. This role involved a against, and 2 abstained). huge workload preparing, cooking, and cleaning after every meal. Voting in favour of the bill Thank you to our valued supporters who donated sponsorship were: 3 members of the money to individual walkers and to the overall campaign. Liberal Party (Richard Della- Riva, Bernie Finn & Gordon FEDERAL ELECTION 2 JULY 2016 Rich-Phillips); 3 members of the ALP (Daniel Mulino, Adem The Federal Election and You Somyurek & Nazih Elasmar); Those of us for whom the life issues have top priority when it 2 members of the Shooters & comes to voting for members of parliament, need to have some Dr. -

Research Paper

Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Research Paper Research Paper The 2014 Victorian State Election No. 1, June 2015 Bella Lesman Rachel Macreadie Dr Catriona Ross Paige Darby Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank their colleagues in the Research & Inquiries Service, Alice Jonas and Marianne Aroozoo for their checking of the statistical tables, proof-reading and suggestions and Debra Reeves for proof-reading. Thanks also to Paul Thornton-Smith and the Victorian Electoral Commission for permission to re-produce their election results maps, for two-party preferred results and swing data based on the redivision of electoral boundaries, and for their advice. Thanks also to Professor Brian Costar, Associate Professor Paul Strangio, Nathaniel Reader, research officer from the Parliament of Victoria’s Electoral Matters Committee, and Bridget Noonan, Deputy Clerk of the Victorian Legislative Assembly for reading a draft of this paper and for their suggestions and comments. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) © 2015 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). -

59Th PARLIAMENT MEMBERS of the LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL

VICTORIA - 59th PARLIAMENT MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Parliament House, Spring Street, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 (03) 9651 8678 [email protected] www.parliament.vic.gov.au As at 1 October 2021 Member (M.L.C) Region Party Address Atkinson, Mr Bruce Eastern Metropolitan LP R19B, Level 3, West 5 Car Park Entrance, Eastland Shopping Centre, 171-175 Maroondah Highway, Ringwood, VIC, 3134 (03) 9877 7188 [email protected] Bach, Dr Matthew Eastern Metropolitan LP Suite 1, 10-12 Blackburn Road, Blackburn, VIC, 3130 (03) 9878 4113 [email protected] Barton, Mr Rodney Eastern Metropolitan TM 128 Ayr Street, Doncaster, VIC, 3108 (03) 9850 8600 [email protected] https://rodbarton.com.au Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RodBartonMP/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/rodbarton4 Bath, Ms Melina Eastern Victoria NAT Shop 2, 181 Franklin Street, Traralgon, VIC, 3844 (03) 5174 7066 [email protected] Bourman, Mr Jeff Eastern Victoria SFP Unit 1, 9 Napier Street, Warragul, VIC, 3820 (03) 5623 2999 [email protected] Crozier, Ms Georgie Southern Metropolitan LP Suite 1, 780 Riversdale Road, Camberwell, VIC, 3124 (03) 7005 8699 [email protected] Cumming, Dr Catherine Western Metropolitan Ind 75 Victoria Street, Seddon, VIC, 3011 (03) 9689 6373 [email protected] Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/crcumming1/ Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/crcumming1 Davis, The Hon. David Southern Metropolitan LP 1/670 Chapel Street, South Yarra, VIC, 3141 (03) 9827 6655 [email protected] Elasmar, The Hon. -

Transcript(PDF 270.35

TRANSCRIPT STANDING COMMITTEE ON THE ENVIRONMENT AND PLANNING Inquiry into fire season preparedness Melbourne — 3 August 2016 Members Mr David Davis — Chair Ms Samantha Dunn Ms Harriet Shing — Deputy Chair Mr Adem Somyurek Ms Melina Bath Ms Gayle Tierney Mr Richard Dalla-Riva Mr Daniel Young Substitute Member Mr Greg Barber Participating Members Mr Jeff Bourman Mr James Purcell Ms Colleen Hartland Mr Simon Ramsay Staff Acting Secretary: Mr Joel Hallinan Research assistant: Ms Annemarie Burt Witnesses Mr Greg Smith (sworn), Chair, Ms Frances Diver (affirmed), CEO, and Mr Steve Warrington (affirmed), Chief Officer, Country Fire Authority. 3 August 2016 Standing Committee on the Environment and Planning 1 The CHAIR — I welcome witnesses Frances Diver, Steve Warrington and Greg Smith to the inquiry on fire season preparedness of the environment and planning committee. I indicate that all evidence taken at this hearing is protected by parliamentary privilege. Therefore you are protected against any action for what you say here today, but if you go outside and repeat those matters, those comments may not be protected by this privilege. I ask that the chief officer, the chairman and the CEO of the CFA please provide a short submission, and then we will follow with some questions. Ms DIVER — Sure. Thanks very much. I might make a start, to just give a general introduction, and then I will hand over to Steve Warrington, who has a pre-prepared PowerPoint presentation. Firstly, I thank the committee for their interest in the Country Fire Authority. We are pleased to be able to come here today to talk about fire preparedness for the season ahead. -

Transcript Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee

TRANSCRIPT LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ECONOMY AND INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE Inquiry into the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism and Events Sectors Melbourne—Wednesday, 16 June 2021 (via videoconference) MEMBERS Mr Enver Erdogan—Chair Mrs Bev McArthur Mr Bernie Finn—Deputy Chair Mr Tim Quilty Mr Rodney Barton Mr Lee Tarlamis Mr Mark Gepp PARTICIPATING MEMBERS Dr Matthew Bach Mr Edward O’Donohue Ms Melina Bath Mr Craig Ondarchie Dr Catherine Cumming Mr Gordon Rich-Phillips Mr David Davis Ms Harriet Shing Mr David Limbrick Ms Kaushaliya Vaghela Ms Wendy Lovell Ms Sheena Watt Mr Andy Meddick Wednesday, 16 June 2021 Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee 1 WITNESS Mr Terry Robinson, Chief Executive Officer, Destination Gippsland. The CHAIR: I declare open the Economy and Infrastructure Committee public hearing for the Inquiry into the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism and Events Sectors. Please ensure that mobile phones are switched to silent and that any background noise is minimised. I wish to begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land, and I pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging. I would also like to add that the committee had planned to hold today’s hearing in Traralgon. On behalf of the committee may I express our concerns and best wishes to everyone in Traralgon and other parts of Gippsland affected by last week’s storm. We hope you stay safe and you are able to recover from the storm as quickly as possible. My name is Enver Erdogan, and I am Chair of the committee.