Opening a Museum for Everyone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year of Le Nôtre

ch VER ât Sail ecouverture conférence de presse version déf.indd 1 aules 18/01/2012 13:01:48 3 CONTENTS Press conference - 26 january 2012 Foreword 4 Versailles on the move 7 The exhibitions in versailles 8 Versailles to arras 12 Events 13 Shows 15 Versailles rediscovered 19 Refurnishing versailles 21 What the rooms were used for 26 Versailles and its research centre 28 Versailles for all 31 2011, Better knowledge of the visitors to versailles 32 A better welcome, more information 34 Winning the loyalty of visitors 40 Versailles under construction 42 The development plan 43 Safeguarding and developing our heritage 48 More on versailles 60 Budget 61 Developing and enhancing the brand 63 Sponsors of versailles 64 Versailles in figures 65 Appendices 67 Background of the palace of versailles 68 Versailles in brief 70 Sponsors of the palace of versailles 72 List of the acquisitions 74 Advice for visitors 78 Contacts 80 4 Foreword This is the first time since I was appointed the effects of the work programme of the first phase President of the Public Establishment of the Palace, of the “Grand Versailles” development plan will be Museum and National Estate of Versailles that I considerable. But the creation of this gallery which have had the pleasure of meeting the press. will present the transformations of the estate since Flanked by the team that marks the continuity Louis XIII built his hunting lodge here marks our and the solidity of this institution, I will review the determination to provide better reception facilities remarkable results of 2011 and, above all, the major for our constantly growing numbers of visitors by projects of the year ahead of us. -

Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17Th & 18Th Centuries

12/09/2017 Cycladic Figure c 2500 BC Minoan Bull Leaper c 1500 BC Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17th & 18th centuries Sophia Schliemann wearing “Helen’s Jewellery” Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Heracles from the Parthenon Paris and Helen krater c 700 BC Roman copy of Hellenistic bust of Homer Small bronze statue of Alexander the Great c 100 BC Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Judgement of Paris from Etruria c 550 BC Tiberius sword hilt showing Augustus as Jupiter Arrival of Aeneas in Italy Blacas Cameo showing Augustus with aegis breastplate Augustus of Prima Porta c 25 AD Dr William Sterling (discovered 1863) Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 1 12/09/2017 Romulus and Remus on the Franks Casket c 700 AD Siege of Jerusalem from the Franks Casket Mantegna Triumph of Caesar Mantua c 1490 Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry c 1410 – tapestry of Trojan War Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk The Colosseum Rome The Parthenon Athens The Pantheon Rome Artist’s Impression of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus showing surviving sculpture Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Hera and Zeus on the Parthenon Frieze in the British Museum Hermes, Dionysus, Demeter and Ares on the Parthenon Frieze Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk -

Why Paris Region Is the #1 Destination on the Planet: with 50 Million Visitors Each Year, the Area Is Synonymous with “Art De Vivre”, Culture, Gastronomy and History

Saint-Denis Basilicum and Maison de la Légion d’Honneur © Plaine Commune, Direction du Développement Economique, SEPE, Som VOSAVANH-DEPLAGNE - Plain of Montesson © CSAGBS-EDesaux - La Défense Business district © 11h45 for Defacto - Campus © Ecole Polytechnique Paris/Saclay. J. Barande - © Ville d’Enghien-les-Bains - INSEAD Fontainebleau © Yann Piriou - Charenton-le-Pont – Ivry-sur-Seine © ParisEstMarne&Bois - Bassin de La Villette, Paris Plages © CRT Ile-de-France - Tripelon-Jarry Welcome to Paris Region Paris Region Facts and Figures 2020 lays out a panorama of the region’s economic dynamism and social life, Europe’s business positioning it among the leading regions in Europe and worldwide. & innovation With its fundamental key indicators, the brochure “Paris Region Facts and powerhouse Figures 2020” is a tool for decision and action for companies and economic stakeholders. It is useful to economic and political leaders of the region and to all those who want to have a global vision of this dynamic regional economy. Paris Region Facts and Figures 2020 is a collaborative publication produced by Choose Paris Region, L’Institut Paris Region and the Paris Île-de-France Regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Jardin_des_tuileries_Tour_Eiffel_01_tvb CRT IDF-Van Biesen Table of contents 5 Welcome to Paris Region 27 Digital Infrastructure 6 Overview 28 Real Estate 10 Population 30 Transport and Mobility 12 Economy and Business 32 Logistics 18 Employment 34 Meetings and Exhibitions 20 Education 36 Tourism and Quality of life 24 R&D and Innovation Paris Region Facts & Figures 2020 Welcome to Paris Region 5 A dynamic and A business fast-growing region and innovation powerhouse Paris Region, The Paris Region is a truly global region which accounts for 23.3% The highest GDP in the European of France’s workforce, 31% of Union (EU28) in billions of euros. -

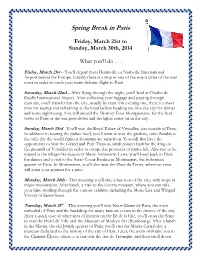

Spring Break in Paris

Spring Break in Paris Friday, March 21st to Sunday, March 30th, 2014 What you’ll do . Friday, March 21st – You’ll depart from Huntsville or Nashville International Airport bound for Europe. Usually there is a stop in one of the major cities of the east coast in order to catch your trans-Atlantic flight to Paris. Saturday, March 22nd – After flying through the night, you’ll land at Charles de Gaulle International Airport. After collecting your luggage and passing through customs, you’ll transfer into the city, usually by train. On evening one, there’s a short time for resting and refreshing at the hotel before heading out into the city for dinner and some sightseeing. You will ascend the 58-story Tour Montparnasse for the best views of Paris as the sun goes down and the lights come on in the city. Sunday, March 23rd– You’ll visit the Royal Palace of Versailles, just outside of Paris. In addition to touring the palace itself, you’ll want to visit the gardens, since Sunday is the only day the world-famous fountains are turned on. You will also have the opportunity to visit the Grand and Petit Trianon, small palaces built by the king on the grounds of Versailles in order to escape the pressures of palace life. Also not to be missed is the village-like hameau of Marie Antoinette. Later, you’ll head back to Paris for dinner and a visit to the Sacré-Coeur Basilica in Montmartre, the bohemian quarter of Paris. In Montmartre, you’ll also visit the Place du Tertre, where an artist will paint your portrait for a price. -

Court of Versailles: the Reign of Louis XIV

Court of Versailles: The Reign of Louis XIV BearMUN 2020 Chair: Tarun Sreedhar Crisis Director: Nicole Ru Table of Contents Welcome Letters 2 France before Louis XIV 4 Religious History in France 4 Rise of Calvinism 4 Religious Violence Takes Hold 5 Henry IV and the Edict of Nantes 6 Louis XIII 7 Louis XIII and Huguenot Uprisings 7 Domestic and Foreign Policy before under Louis XIII 9 The Influence of Cardinal Richelieu 9 Early Days of Louis XIV’s Reign (1643-1661) 12 Anne of Austria & Cardinal Jules Mazarin 12 Foreign Policy 12 Internal Unrest 15 Louis XIV Assumes Control 17 Economy 17 Religion 19 Foreign Policy 20 War of Devolution 20 Franco-Dutch War 21 Internal Politics 22 Arts 24 Construction of the Palace of Versailles 24 Current Situation 25 Questions to Consider 26 Character List 31 BearMUN 2020 1 Delegates, My name is Tarun Sreedhar and as your Chair, it's my pleasure to welcome you to the Court of Versailles! Having a great interest in European and political history, I'm eager to observe how the court balances issues regarding the French economy and foreign policy, all the while maintaining a good relationship with the King regardless of in-court politics. About me: I'm double majoring in Computer Science and Business at Cal, with a minor in Public Policy. I've been involved in MUN in both the high school and college circuits for 6 years now. Besides MUN, I'm also involved in tech startup incubation and consulting both on and off-campus. When I'm free, I'm either binging TV (favorite shows are Game of Thrones, House of Cards, and Peaky Blinders) or rooting for the Lakers. -

Admirable Trees of Through Two World Wars and Witnessed the Nation’S Greatest Dramas Versailles

Admirable trees estate of versailles estate With Patronage of maison rémy martin The history of France from tree to tree Established in 1724 and granted Royal Approval in 1738 by Louis XV, Trees have so many stories to tell, hidden away in their shadows. At Maison Rémy Martin shares with the Palace of Versailles an absolute Versailles, these stories combine into a veritable epic, considering respect of time, a spirit of openness and innovation, a willingness to that some of its trees have, from the tips of their leafy crowns, seen pass on its exceptional knowledge and respect for the environment the kings of France come and go, observed the Revolution, lived – all of which are values that connect it to the Admirable Trees of through two World Wars and witnessed the nation’s greatest dramas Versailles. and most joyous celebrations. Strolling from tree to tree is like walking through part of the history of France, encompassing the influence of Louis XIV, the experi- ments of Louis XV, the passion for hunting of Louis XVI, as well as the great maritime expeditions and the antics of Marie-Antoinette. It also calls to mind the unending renewal of these fragile giants, which can be toppled by a strong gust and need many years to grow back again. Pedunculate oak, Trianon forecourts; planted during the reign of Louis XIV, in 1668, this oak is the doyen of the trees on the Estate of Versailles 1 2 From the French-style gardens in front of the Palace to the English garden at Trianon, the Estate of Versailles is dotted with extraordi- nary trees. -

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

Key to the People and Art in Samuel F. B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre

15 21 26 2 13 4 8 32 35 22 5 16 27 14 33 1 9 6 23 17 28 34 3 36 7 10 24 18 29 39 C 19 31 11 12 G 20 25 30 38 37 40 D A F E H B Key to the People and Art in Samuel F. B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre In an effort to educate his American audience, Samuel Morse published Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures. Thirty-seven in Number, from the Most Celebrated Masters, Copied into the “Gallery of the Louvre” (New York, 1833). The updated version of Morse’s key to the pictures presented here reflects current scholarship. Although Morse never identified the people represented in his painting, this key includes the possible identities of some of them. Exiting the gallery are a woman and little girl dressed in provincial costumes, suggesting the broad appeal of the Louvre and the educational benefits it afforded. PEOPLE 19. Paolo Caliari, known as Veronese (1528–1588, Italian), Christ Carrying A. Samuel F. B. Morse the Cross B. Susan Walker Morse, daughter of Morse 20. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519, Italian), Mona Lisa C. James Fenimore Cooper, author and friend of Morse 21. Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio (c. 1489?–1534, Italian), Mystic D. Susan DeLancy Fenimore Cooper Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria E. Susan Fenimore Cooper, daughter of James and Susan DeLancy 22. Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640, Flemish), Lot and His Family Fleeing Fenimore Cooper Sodom F. Richard W. Habersham, artist and Morse’s roommate in Paris 23. -

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Jacques-Louis David THE FAREWELL OF TELEMACHUS AND EUCHARIS Dorothy Johnson GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my parents, Alice and John Winter, and for Johnny Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748 — 1825). The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818 Benedicte Gilman, Editor (detail). Oil on canvas, 87.2 x 103 cm (34% x 40/2 in.). Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum (87.PA.27). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: (Getty objects, 87.PA.27, 86.PA.740) Jacques-Louis David. Self-Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64 cm (31/8 x 25/4 in.). Paris, © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Museum Musee du Louvre (3705). © Photo R.M.N. 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise P.O. Box 2112 indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong Johnson, Dorothy. Jacques-Louis David, the Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis / Dorothy Johnson, p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references (p. — ). ISBN 0-89236-236-7 i. David, Jacques Louis, 1748 — 1825. Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis. 2. David, Jacques Louis, 1748-1825 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Telemachus (Greek mythology)—Art. 4. Eucharis (Greek mythology)—Art. I. Title. -

Artemis: Depictions of Form and Femininity in Sculpture Laura G

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2017 Artemis: Depictions of Form and Femininity in Sculpture Laura G. Waters Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the Sculpture Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Artemis: Depictions of Form and Femininity in Sculpture" (2017). Student Publications. 658. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/658 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Artemis: Depictions of Form and Femininity in Sculpture Abstract Grecian sculpture has been the subject of investigation for centuries. More recently, however, emphasis in the field of Art History on the politics of gender and sexuality portrayal have opened new avenues for investigation of those old statues. In depicting gender, Ancient Greek statuary can veer towards the non- binary, with the most striking examples being works depicting Hermaphroditos and ‘his’ bodily form. Yet even within the binary, there are complications. Depictions of the goddess Artemis are chief among these complications of the binary, with even more contradiction, subtext, and varied interpretation than representations of Amazons. The umen rous ways Artemis has been portrayed over the years highlight her multifarious aspects, but often paint a contradictory portrait of her femininity. Is she the wild mother? The asexual huntress? Or is she a tempting virgin, whose purity is at risk? Depictions of her in sculptural form, deliberately composed, offer answers. -

Insights from Stourhead Gardens

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Myth In Reception: Insights From Stourhead Gardens Thesis How to cite: Harrison, John Edward (2018). Myth In Reception: Insights From Stourhead Gardens. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2017 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000d97e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Myth in reception: Insights from Stourhead gardens John Edward Harrison BSc (Hons) Psychology, University of Hertfordshire, UK Dip CS, Open University, UK PhD Neuroscience, University of London, UK Thesis submitted to The Open University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) The Open University December 2017 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis represents my own work, except where due acknowledgement is made, and that is has not been previously submitted to the Open University or to any other institution for a degree, diploma or other qualification. 2 Abstract The focus of my thesis is the reception of classical myth in Georgian Britain as exemplified by responses to the garden imagery at Stourhead, Wiltshire. Previous explanations have tended to the view that the gardens were designed to recapitulate Virgil’s Aeneid. -

Breaking with Convention: Mme De Pompadour's Refashioning of The

Breaking with Convention: Mme de Pompadour’s Refashioning of the ‘Self’ Through the Bellevue Turqueries Mandy Paige-Lovingood A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art History. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Melissa L. Hyde Cary Levine John Bowles ©2017 Mandy Paige-Lovingood ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MANDY PAIGE-LOVINGOOD: Breaking with Convention: Mme de Pompadour’s Refashioning of the ‘Self’ Through the Bellevue Turqueries (Under the direction of Dr. Melissa Hyde) In 1750 the sexual relationship between Mme Pompadour and Louis XV ended, resulting in the maîtresse-en-titre’s move out of Versailles and into the Château de Bellevue. Designed by Pompadour and with the financial support of the king, the château offered her a place away from court etiquette and criticism, a private home for her and Louis XV to relax. Within Bellevue, her bedroom (la chambre a la turq) was decorated with Turkish furnishings, textiles and Carle Van Loo’s three-portrait harem series. Specifically, my thesis will explore Pompadour’s chambre a la turque and Van Loo’s A Sultana Taking Coffee, the only self-portrait of Mme de Pompadour in the series, to exhibit her adoption and depiction of the French fashion trend of turquerie. Here, I suggest Pompadour’s adoption of harem masquerade was a political campaign aimed at reclaiming and magnifying her social and political dislocation from Louis XV’s court, as well as an alternative appraoch to the French definition of ‘woman,’ whereby she represented herself as an elite and desired ‘other’: the Ottoman woman.