G. Aijmer a Structural Approach to Chinese Ancestor Worship In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China

Entropy 2014, 16, 6313-6337; doi:10.3390/e16126313 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China Xixi Chen 1, Tao Hu 1, Fu Ren 1,2,*, Deng Chen 1, Lan Li 1 and Nan Gao 1 1 School of Resource and Environment Science, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (X.C.); [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (N.G.) 2 Key Laboratory of Geographical Information System, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86-27-87664557; Fax: +86-27-68778893. External Editor: Hwa-Lung Yu Received: 20 July 2014; in revised form: 31 October 2014 / Accepted: 26 November 2014 / Published: 1 December 2014 Abstract: Hubei Province is the hub of communications in central China, which directly determines its strategic position in the country’s development. Additionally, Hubei Province is well-known for its diverse landforms, including mountains, hills, mounds and plains. This area is called “The Province of Thousand Lakes” due to the abundance of water resources. Geographical names are exclusive names given to physical or anthropogenic geographic entities at specific spatial locations and are important signs by which humans understand natural and human activities. In this study, geographic information systems (GIS) technology is adopted to establish a geodatabase of geographical names with particular characteristics in Hubei Province and extract certain geomorphologic and environmental factors. -

A Simple Model to Assess Wuhan Lock-Down Effect and Region Efforts

A simple model to assess Wuhan lock-down effect and region efforts during COVID-19 epidemic in China Mainland Zheming Yuan#, Yi Xiao#, Zhijun Dai, Jianjun Huang & Yuan Chen* Hunan Engineering & Technology Research Centre for Agricultural Big Data Analysis & Decision-making, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, Hunan, 410128, China. #These authors contributed equally to this work. * Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.C. (email: [email protected]) (Submitted: 29 February 2020 – Published online: 2 March 2020) DISCLAIMER This paper was submitted to the Bulletin of the World Health Organization and was posted to the COVID-19 open site, according to the protocol for public health emergencies for international concern as described in Vasee Moorthy et al. (http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.251561). The information herein is available for unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited as indicated by the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Intergovernmental Organizations licence (CC BY IGO 3.0). RECOMMENDED CITATION Yuan Z, Xiao Y, Dai Z, Huang J & Chen Y. A simple model to assess Wuhan lock-down effect and region efforts during COVID-19 epidemic in China Mainland [Preprint]. Bull World Health Organ. E-pub: 02 March 2020. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.254045 Abstract: Since COVID-19 emerged in early December, 2019 in Wuhan and swept across China Mainland, a series of large-scale public health interventions, especially Wuhan lock-down combined with nationwide traffic restrictions and Stay At Home Movement, have been taken by the government to control the epidemic. -

5 Mitigation Measures of Environment Influence

E4803 V2 Certificate No.: GHPZJZ No. 2608 Public Disclosure Authorized Traffic Integration Demonstration Project of Wuhan Public Disclosure Authorized City Circle Supported by World Bank Loan- Urban Transport Infrastructure Subproject in Anlu, Xiaogan Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Management Plan Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: Hubei Gimbol Environment Technology Co., Ltd Anlu Yunan Asset Management Co., Ltd. March, 2015 1 Contents 1 Preface ……………………………………………………………………………..1 1.1 EMP objective………………………………………………..……….….… 1 1.2 EMP design ……………………………………………………………………….……………………..2 2 Environmental Policies and Regulations Documents …………………………..4 2.1 Related laws and regulations …………………………………………………………….………4 2.2 Technical specifications and standards ………………………………………….………….6 2.3Safety guarantee policies of the World Bank ………………………….………………….7 2.4 Related technical documents ………………………………………………………….…………8 2.5 Applicable standards ……………………………………………………………………..………….8 3 Project Overview ………………………………………………………………...14 3.1Project overview ………………………………………………………………………..……….……14 3.2 Construction organization ……………………………………………………………..………..17 4. Environmental Impact of the Project …………………………………….……19 4.1 Goal of environmental protection ……………………………………………………..…….19 4.2 Identification of environmental impact of engineering construction ……..…54 4.3 Influence on ecological environment …………………………………………..………….57 4.4 Influence on water environment ………………………………………………………………61 4.5 Impact on acoustic environment ………………………………………………………………65 4.6 Ambient -

Spatial-Temporal Features of Wuhan Urban Agglomeration Regional Development Pattern—Based on DMSP/OLS Night Light Data

Journal of Building Construction and Planning Research, 2017, 5, 14-29 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbcpr ISSN Online: 2328-4897 ISSN Print: 2328-4889 Spatial-Temporal Features of Wuhan Urban Agglomeration Regional Development Pattern—Based on DMSP/OLS Night Light Data Mengjie Zhang1*, Wenwei Miao1, Yingpin Yang2, Chong Peng1, Yaping Huang1 1School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China 2Institute of Remote Sensing and Digital Earth, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China How to cite this paper: Zhang, M.J., Miao, Abstract W.W., Yang, Y.P., Peng, C. and Huang, Y.P. (2017) Spatial-Temporal Features of Wu- Based on the night light data, urban area data, and economic data of Wuhan han Urban Agglomeration Regional De- Urban Agglomeration from 2009 to 2015, we use spatial correlation dimen- velopment Pattern—Based on DMSP/OLS sion, spatial self-correlation analysis and weighted standard deviation ellipse Night Light Data. Journal of Building Con- struction and Planning Research, 5, 14-29. to identify the general characteristics and dynamic evolution characteristics of https://doi.org/10.4236/jbcpr.2017.51002 urban spatial pattern and economic disparity pattern. The research results prove that: between 2009 and 2013, Wuhan Urban Agglomeration expanded Received: February 3, 2017 Accepted: March 5, 2017 gradually from northwest to southeast and presented the dynamic evolution Published: March 8, 2017 features of “along the river and the road”. The spatial structure is obvious, forming the pattern of “core-periphery”. The development of Wuhan Urban Copyright © 2017 by authors and Agglomeration has obvious imbalance in economic geography space, pre- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. -

Present Status, Driving Forces and Pattern Optimization of Territory in Hubei Province, China Tingke Wu, Man Yuan

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Environmental and Ecological Engineering Vol:13, No:5, 2019 Present Status, Driving Forces and Pattern Optimization of Territory in Hubei Province, China Tingke Wu, Man Yuan market failure [4]. In fact, spatial planning system of China is Abstract—“National Territorial Planning (2016-2030)” was not perfect. It is a crucial problem that land resources have been issued by the State Council of China in 2017. As an important unordered and decentralized developed and overexploited so initiative of putting it into effect, territorial planning at provincial level that ecological space and agricultural space are seriously makes overall arrangement of territorial development, resources and squeezed. In this regard, territorial planning makes crucial environment protection, comprehensive renovation and security system construction. Hubei province, as the pivot of the “Rise of attempt to realize the "Multi-Plan Integration" mode and Central China” national strategy, is now confronted with great contributes to spatial planning system reform. It is also opportunities and challenges in territorial development, protection, conducive to improving land use regulation and enhancing and renovation. Territorial spatial pattern experiences long time territorial spatial governance ability. evolution, influenced by multiple internal and external driving forces. Territorial spatial pattern is the result of land use conversion It is not clear what are the main causes of its formation and what are for a long period. Land use change, as the significant effective ways of optimizing it. By analyzing land use data in 2016, this paper reveals present status of territory in Hubei. Combined with manifestation of human activities’ impact on natural economic and social data and construction information, driving forces ecosystems, has always been a specific field of global climate of territorial spatial pattern are then analyzed. -

Impact of the COVID-19 Event on Air Quality in Central China

Special Issue on COVID-19 Aerosol Drivers, Impacts and Mitigation (I) Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 20: 915–929, 2020 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2020.04.0150 Impact of the COVID-19 Event on Air Quality in Central China Kaijie Xu1, Kangping Cui1*, Li-Hao Young2*, Yen-Kung Hsieh3, Ya-Fen Wang4, Jiajia Zhang1, Shun Wan1 1 School of Resources and Environmental Engineering, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 230009, China 2 Department of Occupational Safety and Health, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan 3 Marine Ecology and Conservation Research Center, National Academy of Marine Research, Kaohsiung 80661, Taiwan 4 Department of Environmental Engineering, Chung-Yuan Christian University, Taoyuan 32023, Taiwan ABSTRACT In early 2020, the COVID-19 epidemic spread globally. This study investigated the air quality of three cities in Hubei Province, Wuhan, Jingmen, and Enshi, central China, from January to March 2017–2020 to analyze the impact of the epidemic prevention and control actions on air quality. The results indicated that in the three cities, during February 2020, when the epidemic prevention and control actions were taken, the average concentrations of atmospheric PM2.5, PM10, SO2, –3 –3 CO, and NO2 in the three cities were 46.1 µg m , 50.8 µg m , 2.56 ppb, 0.60 ppm, and 6.70 ppb, and were 30.1%, 40.5%, 33.4%, 27.9%, and 61.4% lower than the levels in February 2017–2019, respectively. However, the average O3 concentration (23.1, 32.4, and 40.2 ppb) in 2020 did not show a significant decrease, and even increased by 12.7%, 14.3%, and 11.6% in January, February, and March, respectively. -

Are China's Water Resources for Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence from Hubei Province

sustainability Article Are China’s Water Resources for Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence from Hubei Province Hao Jin and Shuai Huang * School of Public Economics and Administration, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai 200433, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-21-65903686 Abstract: We assessed the sustainability of agricultural water resources in Hubei Province, a typical agricultural province in central China, for a decade (2008–2018). Since traditional evaluation models often consider only the distance between the evaluation point and the positive or negative ideal solution, we introduce gray correlation analysis and construct a new sustainability evaluation model. Our research results show that only one city had excellent sustainable development capacity of agricultural water resources, and the evaluation value of eight cities fluctuated by around 0.5 (the median of the evaluation result), while the sustainable development capacity of agricultural water resources in other cities was relatively poor. Our findings not only reflect the differences in the natural conditions of water resources among various cities in Hubei, but also the impact of the cities’ policies to ensure efficient agricultural water use for sustainable development. The indicators and methods Citation: Jin, H.; Huang, S. Are in this research are not difficult to obtain in most countries and regions of the world. Therefore, the China’s Water Resources for indicator system we have established by this research could be used to study the sustainability of Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence agricultural water resources in other countries, regions, or cities. from Hubei Province. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3510. https://doi.org/ Keywords: water resources; agricultural water resources; sustainability; gray correlation analysis; 10.3390/su13063510 evaluation model Academic Editors: Daniela Malcangio, Alan Cuthbertson, Juan 1. -

Hubei Province Overview

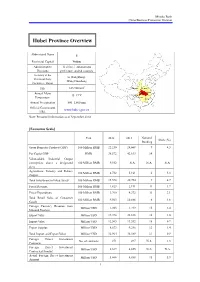

Mizuho Bank China Business Promotion Division Hubei Province Overview Abbreviated Name E Provincial Capital Wuhan Administrative 12 cities, 1 autonomous Divisions prefecture, and 64 counties Secretary of the Li Hongzhong; Provincial Party Wang Guosheng Committee; Mayor 2 Size 185,900 km Shaanxi Henan Annual Mean Hubei Anhui 15–17°C Chongqing Temperature Hunan Jiangxi Annual Precipitation 800–1,600 mm Official Government www.hubei.gov.cn URL Note: Personnel information as of September 2014 [Economic Scale] Unit 2012 2013 National Share (%) Ranking Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 100 Million RMB 22,250 24,668 9 4.3 Per Capita GDP RMB 38,572 42,613 14 - Value-added Industrial Output (enterprises above a designated 100 Million RMB 9,552 N.A. N.A. N.A. size) Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery 100 Million RMB 4,732 5,161 6 5.3 Output Total Investment in Fixed Assets 100 Million RMB 15,578 20,754 9 4.7 Fiscal Revenue 100 Million RMB 1,823 2,191 11 1.7 Fiscal Expenditure 100 Million RMB 3,760 4,372 11 3.1 Total Retail Sales of Consumer 100 Million RMB 9,563 10,886 6 4.6 Goods Foreign Currency Revenue from Million USD 1,203 1,219 15 2.4 Inbound Tourism Export Value Million USD 19,398 22,838 16 1.0 Import Value Million USD 12,565 13,552 18 0.7 Export Surplus Million USD 6,833 9,286 12 1.4 Total Import and Export Value Million USD 31,964 36,389 17 0.9 Foreign Direct Investment No. -

World Bank Document

E1678 V2 Public Disclosure Authorized Mid-term Adjustment for WB Financed Han River Urban Environment Improvement Project Public Disclosure Authorized Report on Environment Management Plan Public Disclosure Authorized WB Financed Han River Basin Pollution Control PMO Public Disclosure Authorized The JV of Hubei Xinbao Science & Technology Co. Ltd and Wuhan University January 2014 Table of Content Chapter I Summary ...................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Project Mid-term Adjustment Introduction ......................................................... 3 1.2 EMP Adjustment Basis ......................................................................................... 5 1.2.1 Relevant Laws and Regulations ................................................................ 5 1.2.2 Regulations of Departments and Local Government ................................ 7 1.2.3 Main Technical Specifications .................................................................. 8 1.2.4 Main Environmental Standards ............................................................... 10 1.2.5 Other Materials ........................................................................................ 12 1.3 Environment Impact Scope Variation Status After Project Mid-term Adjustment .......................................................................................................................................... 13 1.3.1 Hanchuan Sewage Collection Pipeline Network Project ....................... -

Resource Curse” of the Cultivated Land in Main Agricultural Production Regions: a Case Study of Jianghan Plain, Central China

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Spatio-Temporal Differentiation and Driving Mechanism of the “Resource Curse” of the Cultivated Land in Main Agricultural Production Regions: A Case Study of Jianghan Plain, Central China Yuanyuan Zhu, Xiaoqi Zhou , Yilin Gan, Jing Chen and Ruilin Yu * Key Laboratory for Geographical Process Analysis & Simulation Hubei Province, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (Y.G.); [email protected] (J.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-189-8622-9015 Abstract: Cultivated land resources are an important component of natural resources and significant in stabilizing economic and social order and ensuring national food security. Although the research on resource curse has progressed considerably, only a few studies have explored the existence and influencing factors of the resource curse of non-traditional mineral resources. The current study introduced resource curse theory to the cultivated land resources research and directly investigated the county-level relationship between cultivated land resource abundance and economic develop- ment. Meanwhile, the spatiotemporal dynamic pattern and driving factors of the cultivated land curse were evaluated on the cultivated land curse coefficient in China’s Jianghan Plain from 2001 to 2017. The results indicated that the curse coefficient of cultivated land resources in Jianghan Citation: Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gan, Y.; Plain generally shows a downward trend. That is, the curse phenomenon of the cultivated land Chen, J.; Yu, R. Spatio-Temporal resources in large regions did not improve significantly in 2001–2017. -

New Dinosaur Egg Material from Yunxian, Hubei Province, China Resolves the Classification of Dendroolithid Eggs

New dinosaur egg material from Yunxian, Hubei Province, China resolves the classification of dendroolithid eggs SHUKANG ZHANG, TZU-RUEI YANG, ZHENGQI LI, and YONGGUO HU Zhang, S., Yang, T.-R., Li, Z., and Hu, Y. 2018. New dinosaur egg material from Yunxian, Hubei Province, China resolves the classification of dendroolithid eggs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 63 (4): 671–678. The oofamily Dendroolithidae is a distinct group of dinosaur eggs reported from China and Mongolia, which is character- ized by branched eggshell units and irregular pore canals. The ootaxonomic inferences, however, were rarely discussed until now. A colonial nesting site was recently uncovered from the Qinglongshan region, Yunxian, Hubei Province, China. More than 30 dendroolithid egg clutches outcrop on the Tumiaoling Hill, including an extremely gigantic clutch containing 77 eggs. All clutches were exposed in the Upper Cretaceous fluvial-deposited Gaogou For mation. In this study, we emend the diagnosis of the oogenus Placoolithus and assign all dendroolithid eggs from the Tumiaoling Hill to a newly emended oospecies Placoolithus tumiaolingensis that shows greatly variable eggshell microstructure. Moreover, our study also disentangles the previous vexing classification of dendroolithid eggs. We conclude that Dendroolithus tumiaolingensis, D. hongzhaiziensis, and Paradendroolithus qinglongshanensis, all of which were previously reported from Yunxian, should be assigned to the newly emended oospecies Placoolithus tumiaolingensis. Key words: Dendroolithidae, Placoolithus, colonial nesting, Cretaceous, China, Yunxian, Tumiaoling Hill. Shukang Zhang [[email protected]], Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Science, 142 Xizhimenwai Street, Beijing, China. Tzu-Ruei Yang [[email protected]], Steinmann-Institut für Geologie, Mineralogie and Paläontologie, Rheinische-Frie- drich-Wilhelms Universitat Bonn, Nussallee 8, Bonn, Germany. -

Modelling the Effects of Wuhan's Lockdown During COVID-19, China

Research Modelling the effects of Wuhan’s lockdown during COVID-19, China Zheming Yuan,a Yi Xiao,a Zhijun Dai,a Jianjun Huang,a Zhenhai Zhangb & Yuan Chenb Objective To design a simple model to assess the effectiveness of measures to prevent the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) to different regions of mainland China. Methods We extracted data on population movements from an internet company data set and the numbers of confirmed cases of COVID-19 from government sources. On 23 January 2020 all travel in and out of the city of Wuhan was prohibited to control the spread of the disease. We modelled two key factors affecting the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in regions outside Wuhan by 1 March 2020: (i) the total the number of people leaving Wuhan during 20–26 January 2020; and (ii) the number of seed cases from Wuhan before 19 January 2020, represented by the cumulative number of confirmed cases on 29 January 2020. We constructed a regression model to predict the cumulative number of cases in non-Wuhan regions in three assumed epidemic control scenarios. Findings Delaying the start date of control measures by only 3 days would have increased the estimated 30 699 confirmed cases of COVID-19 by 1 March 2020 in regions outside Wuhan by 34.6% (to 41 330 people). Advancing controls by 3 days would reduce infections by 30.8% (to 21 235 people) with basic control measures or 48.6% (to 15 796 people) with strict control measures. Based on standard residual values from the model, we were able to rank regions which were most effective in controlling the epidemic.