Abstract Traditions Postwar Japanese Prints.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7386 Toko Shinoda Sakuhin (Work) Ink and Colour on Silver Leaf Signed to to Lower Right

7386 Toko Shinoda sakuhin (work) ink and colour on silver leaf signed To to lower right H. 17¾" x W. 12" (45cm x 30cm) accompanied by a certificate of registration from Shinoda Toko Kantei Iinkai (Toko Shinoda Appraisal Committee) No.STK16-022 Toko Shinoda (b.1913) was born in Manchuria and moved with her family to Tokyo in 1914. Her father was a keen calligrapher and his interest encouraged Shinoda to practise calligraphy from the age of six years old. By her early twenties she was an independent calligraphy teacher and against her father's wishes decided not to marry but to pursue a career as an artist instead. Shinoda had her first solo calligraphy exhibition in 1936 at Kyukyodo Gallery, Tokyo, and by 1945 she was producing work which departed significantly from the rigid forms of traditional brushwork. Following numerous solo exhibitions of calligraphy her work started to change and in her early forties the focus moved to compositions consisting mainly of thin freely applied brushstrokes. Having a strong-willed character and a desire to develop her creativity beyond the limitations of classical calligraphy and its restrains, Shinoda decided to break away and begun to produce abstract works using traditional materials. This development received severe criticism from the established calligraphy circles of Japan, however her work was recognised by major international art institutions and she was included in two exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1953 and 1954 respectively. In 1956 Shinoda moved to New York where she would be free to further develop her artistic expression and mingle with people who believed in and supported her work such as the painter Franz Kline (1910-1962) and long-term dealer and friend Norman Tolman. -

A4冊子40 1再校0422

篠田桃紅 追悼-空 Homage to TOKO SHINODA 2021 篠田 桃 紅 追悼-空 Homage to TOKO SHINODA 2021 発行 ギャラリーサンカイビ 編集 平田美智子・高島順子 © 2021 〒103-0007 東京都中央区日本橋浜町2-22-5 TEL: 03-5649-3710 https://www.sankaibi.com Published in 2021 by Gallery SanKaïBi Edited by Michiko Hirata・Junko Takashima 2-22-5 Hamacho,Nihonbashi,Chuo-ku,Tokyo 103-0007 TEL: 81-3-5649-3710 https://www.sankaibi.com 追悼 -空 東洋的な伝統美と革新的な造形美を融合させて、「墨象」という新しいジャンルを切り拓き、世界のアートシーン に影響を与えた孤高の美術家、篠田桃紅氏。(3月1日逝去 107歳)3月に生まれたことからお父様が桃に紅で 「桃紅」という雅号をおつけになりました。 「桃紅」は中国の禅林句集「桃紅李白薔薇紫 問著春風總不知」に由来します。桃は紅、季は白、薔薇は紫、それは どうしてなんでしょう?と春風に聞いてみても 知らないと言う。それぞれの花がそれぞれの色に咲くように、人も また相異なるそれぞれの人生があるという教えです。花はなぜ咲くのか、そこには答えがありません。人間社会も 栄枯盛衰を繰り返し、一瞬たりとも移り変わらないものはない。順境と逆境、いかなる時においても一喜一憂す ることなく、宇宙の原理に従って、無為自然に生きる。篠田氏はまさに雅号の通り、首尾貫徹した人生を歩まれた のではないでしょうか。 中国・大連に生まれ、幼い頃から書を学び、戦後に書家として活動を始める一方、水墨による抽象絵画をはじめ 1956年に渡米。米国各地で個展を開き、書と抽象絵画を融合させた新しい作風が高く評価され,時の人とな りました 。 水墨に金銀や朱を交え、幽玄さと鋭い造形感覚を併せ持つ作品は、メトロポリタン美術館やボストン美術館を はじめ、国内外の美術館に収蔵されています。また皇居・御所、京都迎賓館を飾る絵画や在外公館、劇場などの 壁画や緞帳を手がけるほか、代表作は増上寺の壁画や襖絵などがあります。 名文家でも知られ、79年に随筆集「墨いろ」で日本エッセイスト・クラブ賞を受賞。著書「一〇三歳になってわか ったこと」は幅広い年代に支持され、ベストセラーになりました。 「なんにもない、そんなものを描きたい。」と篠 田 氏 は 晩 年 、よ く そ う 語 っ て い ま し た 。空( く う )、す な わ ち 空( そ ら )が 永遠に繋がり切れ目がないように、一滴の水が川になり海に繋がるように、なにものにも囚われず、無執着で開放 された自由な空間の広がりを表現することが、篠田氏の終着点だったのではないかとおもいます。見えないもの や形にならないものを可視の「かたち」にしたい、そんな強い祈りにも似た原始の色や音、香りやかたちが篠田 作品から五感を通して伝わってきます。 「私の命は有限ですが、作品は永遠です。」「言葉ではなく作品から何が伝わるかが重要です。」と常に語っていた 桃紅氏。死の直前まで「もっといいものを創りたい。」と墨と格闘し続けた篠田氏の描く一本一本の広がりのある 線を心ゆくまでご高覧いただければ幸いです。 心よりご冥福をお祈り申しあげます。 ギャラリーサンカイビ 平田 美智子 1. うつろい / Transition 1970年代 和紙に墨・朱・金泥・銀泥 140×93cm Sumi, Cinnabar Ink, Gold Paint, Silver Paint on Paper 2. 四季の歌 小倉百人一首より / Four Seasons from 100 Poems by 100 Poets 2016年 金地に墨・銀泥 60×90cm Sumi, Silver Paint, Gold Leaf on Paper 3. 春暁 / Daybreak 和紙に墨・朱・胡粉 205×148cm Sumi, Cinnabar Ink, White Paint on Paper 4. 5. 叙事詩 / EPIC 月 / Moon 2009年 紙に銀泥・白泥 46×31cm 画仙紙に墨 47×28.5cm White Paint, Silver Paint on Paper Sumi on Paper 6. -

Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations Free

FREE PHILIP GUSTON: COLLECTED WRITINGS, LECTURES, AND CONVERSATIONS PDF Philip Guston,Clark Coolidge,Dore Ashton | 344 pages | 15 Dec 2010 | University of California Press | 9780520257160 | English | Berkerley, United States Philip Guston by Philip Guston, Clark Coolidge - Paperback - University of California Press This is the premier collection of dialogues, talks, and writings by Philip Gustonone of the most intellectually adventurous and poetically gifted of modern painters. Over the course of his life, Guston's wide reading in literature and philosophy deepened his commitment Philip Guston: Collected Writings his art--from his early Abstract Expressionist paintings to his later gritty, intense figurative works. This collection, with many pieces appearing Philip Guston: Collected Writings print for the first time, lets us hear Guston's voice--as the artist delivers a lecture on Renaissance painting, instructs students in a classroom setting, and and Conversations such artists and writers as Piero della Francesca, de Chirico, Picasso, Kafka, Beckett, and Gogol. We're experiencing an enormous and unprecedented order volume Lectures this time. Thanks for your patience and understanding. We ship anywhere in the U. Click here for updates on hours and services. Harvard University harvard. Advanced Search. Our Shelves. Gift Cards. Add a gift card to your order! Choose your denomination:. Thanks for shopping indie! Paperback On Its Way. Details Look Inside Customer Reviews. There are no customer reviews for this item yet. Support Harvard Book Store Shop early, and Conversations local, and help support our future. New This Week Shop this week's new arrivals, updated every Tuesday. Subscribe to Our E-mail Newsletter. -

Art in the Garden 50 Prints and Paintings: Toko Shinoda at 100

Art in the Garden 50 Prints and Paintings: Toko Shinoda at 100 Winter 2013 50 Prints and Paintings: Toko Shinoda at 100 “Certain forms float up in my mind’s Over the past six decades, Japanese artist Toko Shinoda has to have succeeded in this male dominated milieu. Her work has achieved an astonishing international reputation as a master of been noted for the use of “expansive, dynamic brush strokes… eye. Aromas, a blowing breeze, a rain- the ancient art of calligraphy, an accomplished poet, and one of bold and daring, slashing across the paper’s surface, carving out a drenched gust of wind…the air in motion, the most fascinating abstract artists of the modern movement. In landscape inhabited by both warrior and poet.” celebration of her 100th birthday and in honor of the Garden’s my heart in motion. I try to capture 50th anniversary, this special exhibition features a selection of her In 1954, Shinoda was included in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, establishing her as a rising international these vague, evanescent images of the work from The Tolman Collection in Tokyo, known worldwide as a major dealer in contemporary Japanese prints. More significantly, artist. In the 1960s, she began working in lithography, a process instant and put them into vivid form.” Tolman is also the world’s largest publisher of fine print editions that lends itself easily to her dynamic brushstroke style. She has by contemporary Japanese artists. The Tolman Collection has created a number of large murals, the largest of which is 90-feet commissioned 320 exclusive, limited-edition lithographs of long, installed at Zojo-ji, a revered 600-year-old temple in Tokyo. -

ABSTRACT TRADITIONS Postwar Japanese Prints from the Depauw University Permanent Art Collection

ABSTRACT TRADITIONS Postwar Japanese Prints from the DePauw University Permanent Art Collection i Publication of this catalog was made possible with generous support from: Arthur E. Klauser ’45 Asian & World Community Collections Endowment, DePauw University Asian Studies Program, DePauw University David T. Prosser Jr. ’65 E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation Office of Academic Affairs, DePauw University Cover image: TAKAHASHI Rikio Tasteful (No. 5) / 1970s Woodblock print on paper 19-1/16 x 18-1/2 inches DePauw Art Collection: 2015.20.1 Gift of David T. Prosser Jr. ’65 ii ABSTRACT TRADITIONS Postwar Japanese Prints from the DePauw University Permanent Art Collection 3 Acknowledgements 7 Forward Dr. Paul Watt 8 A Passion for New: DePauw’s Postwar Print Collectors Craig Hadley 11 Japanese Postwar Prints – Repurposing the Past, Innovation in the Present Dr. Pauline Ota 25 Sōsaku Hanga and the Monozukuri Spirit Dr. Hiroko Chiba 29 Complicating Modernity in Azechi’s Gloomy Footsteps Taylor Zartman ’15 30 Catalog of Selected Works 82 Selected Bibliography 1 Figure 1. ONCHI Koshiro Poème No. 7 Landscape of May / 1948 Woodblock print on paper 15-3/4 (H) x 19-1/4 inches DePauw Art Collection: 2015.12.1 Gift of David T. Prosser Jr. ’65 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Like so many great colleges and universities, DePauw University can trace its own history – as well as the history and intellectual pursuits of its talented alumni – through generous gifts of artwork. Abstract Traditions examines significant twentieth century holdings drawn from the DePauw University permanent art collection. From Poème No. 7: Landscape of May by Onchi Kōshirō (Figure 1) to abstract works by Hagiwara Hideo (Figure 2), the collection provides a comprehensive overview of experimental printmaking techniques that flourished during the postwar years. -

7082 Toko Shinoda Kaishō (Reminiscence) Ink on Silver Leaf

7082 Toko Shinoda Kaishō (Reminiscence) ink on silver leaf singed and seal, signed and dated 1986 on a gallery label affixed to the reverse H. 23¼" x W. 14¾" (59cm x 37cm) Accompanied by a certificate of registration from Shinoda Toko Kantei Iinkai (Toko Shinoda Appraisal Committee) No.STK16-024 Provenance: Galerie 412, Tokyo Toko Shinoda (b.1913) was born in Manchuria and moved with her family to Tokyo in 1914. Her father was a keen calligrapher and his interest encouraged Shinoda to practise calligraphy from the age of six years old. By her early twenties she was an independent calligraphy teacher and against her father's wishes decided not to marry but to pursue a career as an artist instead. Shinoda had her first solo calligraphy exhibition in 1936 at Kyukyodo Gallery, Tokyo, and by 1945 she was producing work which departed significantly from the rigid forms of traditional brushwork. Following numerous solo exhibitions of calligraphy her work started to change and in her early forties the focus moved to compositions consisting mainly of thin freely applied brushstrokes. Having a strong-willed character and a desire to develop her creativity beyond the limitations of classical calligraphy and its restrains, Shinoda decided to break away and begun to produce abstract works using traditional materials. This development received severe criticism from the established calligraphy circles of Japan, however her work was recognised by major international art institutions and she was included in two exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1953 and 1954 respectively. In 1956 Shinoda moved to New York where she would be free to further develop her artistic expression and mingle with people who believed in and supported her work such as the painter Franz Kline (1910-1962) and long-term dealer and friend Norman Tolman. -

The Louvre's Big Move

Asian Art hires logo 15/8/05 8:34 am Page 1 ASIAN ART The newspaper for collectors, dealers, museums and galleries june 2005 £5.00/US$8/€10 THE LOUVRE’S BIG MOVE Te Louvre has got a march on the history of the museum swung climate change. Te museum is into action. Te cost of the project is located by the Seine, in Paris, in a covered by the Louvre Endowment zone prone to fooding – and, since Fund, with the total price projected 2002, the Paris Prefecture, within to be about Euro 60 million. Te the framework of the food risk answer to the problem was Te protection plan (PPRI), has warned Louvre Conservation Centre, located the Louvre of the risks centennial in Liévin, near Lens, in northern fooding could pose to the museum’s France. Completed in 2019, the collections. Around a quarter of a semi-submerged building stands million works are currently stored in next to the Louvre-Lens Museum, more than 60 diferent locations, which itself was completed in 2012. both within the Louvre palace Te conservation centre makes it (mainly in food-risk zones), and possible to store the reserve elsewhere in temporary storage collections together in a single, spaces – all waiting to be moved to functional, space and allows for the new storage location. optimal conservation conditions. It In 2016, this risk was emphasised also improves access for the scientifc when the Seine fooded its banks, community, researchers, and and the rise in water levels was so conservationists. Te project gave the severe that museum staf had to museum freedom not only to plan, trigger the emergency plan: a 24- but also to have the opportunity to The Musée du Louvre, in Paris, is in the middle of moving its reserve collections to northern France, away from the flood plain hour operation to wrap, pack and modernise the conservation, study, take thousands of objects out of the and work conditions, as well as Lens Museum, a special interpretation at any one time. -

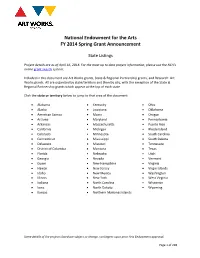

Spring 2014--All Grants Sorted by State

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2014 Spring Grant Announcement State Listings Project details are as of April 16, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Included in this document are Art Works grants, State & Regional Partnership grants, and Research: Art Works grants. All are organized by state/territory and then by city, with the exception of the State & Regional Partnership grants which appear at the top of each state. Click the state or territory below to jump to that area of the document. • Alabama • Kentucky • Ohio • Alaska • Louisiana • Oklahoma • American Samoa • Maine • Oregon • Arizona • Maryland • Pennsylvania • Arkansas • Massachusetts • Puerto Rico • California • Michigan • Rhode Island • Colorado • Minnesota • South Carolina • Connecticut • Mississippi • South Dakota • Delaware • Missouri • Tennessee • District of Columbia • Montana • Texas • Florida • Nebraska • Utah • Georgia • Nevada • Vermont • Guam • New Hampshire • Virginia • Hawaii • New Jersey • Virgin Islands • Idaho • New Mexico • Washington • Illinois • New York • West Virginia • Indiana • North Carolina • Wisconsin • Iowa • North Dakota • Wyoming • Kansas • Northern Marianas Islands Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 228 Alabama Number of Grants: 5 Total Dollar Amount: $841,700 Alabama State Council on the Arts $741,700 Montgomery, AL FIELD/DISCIPLINE: State & Regional To support Partnership Agreement activities. Auburn University Main Campus $55,000 Auburn, AL FIELD/DISCIPLINE: Visual Arts To support the Alabama Prison Arts and Education Project. Through the Department of Human Development and Family Studies in the College of Human Sciences, the university will provide visual arts workshops taught by emerging and established artists for those who are currently incarcerated. -

Issue 3 Crime and Punishment Devolution Travel

The Best of 25 Years of the Scottish Review Issue 3 Crime and Punishment Devolution Travel Edited by Islay McLeod ICS Books To Kenneth Roy, founder of the Scottish Review, mentor and friend, and to all the other contributors who are no longer with us. First published by ICS Books 216 Liberator House Prestwick Airport Prestwick KA9 2PT © Institute of Contemporary Scotland 2020 Cover design: James Hutcheson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-8382831-2-4 Contents Crime and Punishment 1 Dancing with a stranger Magnus Linklater (1996) 2 Insider George Chalmers (1999) 11 Alice's year Fiona MacDonald (1999) 16 Anne Frank and the prisoners Paula Cowan (2009) 23 She took her last breath handcuffed to a guard Kenneth Roy (2013) 26 The last man to be hanged in Scotland returns to haunt us Kenneth Roy (2014) 29 Inside the Vale Prisoner 65595 (2016) 32 The truth about knife crime Kenneth Roy (2016) 36 Crack central Maxwell MacLeod (2016) 39 Rape, and the men who get away with it Kenneth Roy (2017) 42 Polmont boys Kenneth Roy (2017) 44 Spouses who kill Kenneth Roy (2018) 47 Still banging them up Kenneth Roy (2018) 50 The death in prison of Katie Allan Kenneth Roy (2018) 53 Fear and loathing in the gym Kenneth Roy (2018) 55 In defence of 'not proven' verdicts Alistair R -

The Influences of Taoist Philosophy and Cultural Practices on Contemporary Art Practice

1 Change and Continuity: the Influences of Taoist Philosophy and Cultural Practices on Contemporary Art Practice Bonita Ely Doctor of Philosophy 2009 University of Western Sydney 2 The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. ....................................................... 3 Many thanks to my supervisors, Dr. Peter Dallow, Dr. Noelene Lucas and David Cubby for their support, knowledge and guidance. The Chinati Foundation, Marfa Texas, and the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales gave essential support to this research. Thanks also to Marina Grounds Ely, Huy Ky Do, Sandy Edwards and Sue Goldfish, and my colleagues, Allan Giddy, Sylvia Ross, Martin Sims and Emma Price for their support. 4 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................10 CHAPTER 2: A HISTORY OF DISCOURSE – EAST WEST AND BACK AGAIN.........23 RHIZOME #1: Chinoiserie and Zen, installation art and earthworks......................................................25 KU – NOTHINGNESS, THE VOID ...........................................................................................................35 MA – THE IN-BETWEEN ZONE ..............................................................................................................35 WABI SABI – SOLITUDE AND AUSTERITY, -

Leonor Fini Salvador Dali Originals and Graphics from the Dali Bible

VGALLERY&STUDIOOL. 4 NO. 1 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2001 New York The World of the Working Artist Leonor Fini Early Works Leonor Fini “Les tragediennes” 1930-31 Oil on Board 45" x 64" on Board 1930-31 Oil “Les tragediennes” Leonor Fini Salvador Dali Originals and Graphics from The Dali Bible September 7 thru October 7, 2001 CFM Gallery 112 Greene Street, SoHo, New York City 10012 (212) 966-3864 Fax (212) 226-1041 Monday thru Saturday 11am to 6pm Sunday Noon to 6pm [email protected] www.art~smart.com/cfm/ Untitled 2001, acrylic on canvas, 60" x 72" Missy Lipsett September 4-22, 2001 recent paintings “Coney Island Boardwalk,” Monotype, 30" X 22" Pleiades Gallery KELYNN Z. ALDER 530 West 25th St., 4th fl (betwn 10th and 11th Aves.) People and Places • Monotypes and Paintings New York, NY 10001 tel: 646.230.0056 October 16 - November 3, 2001 gallery hours: Tuesday-Saturday, 11:00-6:00pm VIRIDIAN@Chelsea 530 West 25th Street, 4th Floor, NY, NY 10001 Studio tel: 212.369.9795 Tel(212) 414-4040 • www.viridianartists.com e-mail: [email protected] Tuesday - Saturday 11am - 6pm Helene Johnson • Sculptor “En La Plaza De Sanbándia” Terracotta 13"w x 14"deep x 11"h “We Are Sorry” (Didactic Series) 2001, Acrylic, Photographs, Mixed Media Photo by: Zinovenko Photography on Wire Mesh, 60" x 72" x 7" Recent solo exhibitor at the Paul Gazda “Triple Vision” Pen and Brush Club, Inc. Mixed Media Paintings in Three Series Works can be viewed by appointment October 3 - 27, 2001• Reception Thurs Oct. -

EXHIBITING IRELAND in the SIXTIES: ROSC by ANTONIA

EXHIBITING IRELAND IN THE SIXTIES: ROSC by ANTONIA LAURENCE ALLEN B.A., Indiana University, 1996 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standards THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1999 © Antonia Laurence Allen 1999 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, 1 agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) 11 Abstract 1967 in Dublin, Ireland, an exhibition opened its doors to a suspecting public. Rose '67 was a work of art in itself. It purported to display work from fifty of the 'best' international artists in the world. Rose was to occur every four years and be run by a committee who chose a jury of three to select works. Most of the art was contemporary, completed in the previous four years and displayed in a large hall on the grounds of the Royal Dublin Society, famous for its annual Dublin horse show. Like the celebrated Biennales which litter the world, Rose was a product of its homeland, and it is my task in this paper to unravel the specificities of Dublin in the sixties to reveal the cultural significance of this exhibition.