The Responsibility of Intellectuals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Mixed-Methods Content Analysis Case Study of Frames and Ideologies in Mainstream Environmental News a Dissertation Submitted

A Mixed-Methods Content Analysis Case Study of Frames and Ideologies in Mainstream Environmental News A dissertation submitted to the College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by William F. Kelvin December, 2019 Dissertation written by William F. Kelvin B.A., Humboldt State University, 2002 M.A., California State University, Chico, 2009 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2019 Approved by ____________________________________ Danielle Sarver Coombs, Ph.D., Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________ Paul Haridakis, Ph.D., Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________ Yesim Kaptan, Ph.D., Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________ Steven Hook, Ph.D., Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by ____________________________________ Miriam Matteson, Ph.D., Interim Associate Dean, Doctoral Studies Committee ____________________________________ Amy Reynolds, Ph.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information ii Table of Contents Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... ii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ..........................................................................................................................v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth © 2012 PM Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978–1–60486–484–7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927981 Cover: John Yates / www.stealworks.com Interior design by briandesign 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com contents Introduction 1 Robert H. Haworth Section I Anarchism & Education: Learning from Historical Experimentations Dialogue 1 (On a desert island, between friends) 12 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 1 Anarchism, the State, and the Role of Education 14 Justin Mueller chapteR 2 Updating the Anarchist Forecast for Social Justice in Our Compulsory Schools 32 David Gabbard ChapteR 3 Educate, Organize, Emancipate: The Work People’s College and The Industrial Workers of the World 47 Saku Pinta cHAPteR 4 From Deschooling to Unschooling: Rethinking Anarchopedagogy after Ivan Illich 69 Joseph Todd Section II Anarchist Pedagogies in the “Here and Now” Dialogue 2 (In a crowded place, between strangers) 88 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 5 Street Medicine, Anarchism, and Ciencia Popular 90 Matthew Weinstein cHAPteR 6 Anarchist Pedagogy in Action: Paideia, Escuela Libre 107 Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan cHAPteR 7 Spaces of Learning: The Anarchist Free Skool 124 Jeffery Shantz cHAPteR 8 The Nottingham Free School: Notes Toward a Systemization of Praxis 145 Sara C. -

The Life and Politics of Dwight Macdonald. by Munist Left That Was Even Called Politics, Michael Wreszin

though he was entirely serious about his politics and founded and edited for its five-year life in A REBEL IN DEFENSE OF TRADITION: the 1940s an influential journal of the noncom- The Life and Politics of Dwight Macdonald. By munist Left that was even called Politics, Michael Wreszin. Basic Books. 590 pp. $30 Macdonald was not a profound or original po- litical thinker. By the 1950s he abandoned poli- Dwight Macdonald was probably contrary in tics altogether and moved to the New Yorker, his cradle. Of principled opposition, intellectual where lus criticisms of America were framed by independence, and educated crankiness he went glittering commercial endorsements of the very on to make a life's work. Born in Manhattan to way of life he censured. And it is as a cultural upper-middle-class parents in 1906 and edu- critic, a Savonarola against masscult, midcult, cated at scl~oolsappropriate to his class, and kitsch, that he is best remembered. The Macdonald became one of the more conspicuous merging of lug11 and low culture, the homogeni- political, social, and cultural critics in America, zation, the leveling of all values, standards, and and frequently of America, from the 1930s until distinctions struck him as another form of totali- his death in 1982. In this first biography, Wreszin tarianism. guides the reader along the dizzying course of He chose his targets well. The permissiveness Macdonald's shifting political of Webster's Third NmInterna- enthusiasms: the flirtation with tional Dictionary was an abdica- communism, the embrace of tion of responsibilityby an edu- Trotskyite socialism, the unre- cated elite and encouraged an mitting anti-Stalinism, the en- ignorance of tradition; it mir- during opposition to totalitari- rored "a plebeian attitude to- anism and nationalism and the ward language." The "revised state, the pacifism, the ill-con- standard version" of the Bible cealed impatience with the gave up the grandeur of the masses, the deep cultural con- King James version and substi- servatism. -

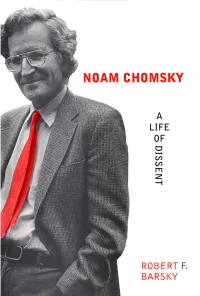

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky Addressing a Crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky addressing a crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989. Noam Chomsky A Life of Dissent Robert F. Barsky ECW PRESS Copyright © ECW PRESS, 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process—electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW PRESS. CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Barsky, Robert F. (Robert Franklin), 1961- Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55022-282-1 (bound) ISBN 1-55022-281-3 (pbk.) 1. Chomsky, Noam. 2. Linguists—United States—Biography. I. Title. P85.C47B371996 410'.92 C96-930295-9 This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and with the assistance of grants provided by the Ontario Arts Council and The Canada Council. Distributed in Canada by General Distribution Services, 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2T6. Distributed in the United States and internationally by The MIT Press. Photographs: Cover (1989), frontispiece (1989), and illustrations 18, 24, 25 (1989), © Elaine Briere; illustration 1 (1992), © Donna Coveney, is used by per- mission of Donna Coveney; illustrations 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20,21,22,23,26, © Necessary Illusions, are used by permission of Mark Achbar and Jeremy Allaire; illustrations 5, 8, 9, 10 (1995), © Robert F. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Dana Polan, Julia Child’s “The French Chef.” Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011. 312 pp. $23.95. Reviewed by Heidi Kroll, U.S. Federal Communications Commission Julia Child became a cultural icon when I was growing up in the 1960s. Her cooking shows on the Public Broadcasting System inspired my mother to purchase her cook- books and use her recipes to make seemingly exotic dishes like soufºé and beef bour- guignon. My ªrst academic position was at a remotely located liberal arts college in Minnesota, and I remember being invited to a fellow faculty member’s home for din- ner where his wife proudly served a delicious beef stew with olives and potatoes from a Julia Child recipe. I myself have prepared Julia Child’s French onion soup and her chocolate and almond cake (reine de saba) for friends and colleagues. I enjoyed her memoir, My Life in France, and the ªlm Julie and Julia, which is based in part on the memoir. I am also a fan of food writers Anthony Bourdain and Ruth Reichl, mainly because I ªnd their light fare a perfect way to kill time on long-distance ºights. So when asked to review Julia Child’s “The French Chef” by Dana Polan, I thought, why not? I soon discovered that my experience watching Julia Child on television and in- dulging in dishes made from her recipes did not adequately prepare me to review a book that takes a scholarly approach to the The French Chef. Polan, a professor of cin- ema studies at New York University, uses the history of Julia Child’s television show The French Chef as a case study to explore the evolution of American television and popular culture in the 1960s and early 1970s. -

Noam Chomsky Written by E-International Relations

Interview - Noam Chomsky Written by E-International Relations This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Interview - Noam Chomsky https://www.e-ir.info/2014/02/03/interview-noam-chomsky/ E-INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, FEB 3 2014 Noam Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received his PhD in linguistics in 1955 from the University of Pennsylvania. From 1951 to 1955, Chomsky was a Junior Fellow of the Harvard University Society of Fellows. The major theoretical viewpoints of his doctoral dissertation appeared in the monographSyntactic Structure in 1957. This formed part of a more extensive work,The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, circulated in mimeograph in 1955 and published in 1975. Chomsky joined the staff of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1955 and in 1961 was appointed full professor. In 1976 he was appointed Institute Professor in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy. Chomsky has lectured at many universities in the US and abroad, and is the recipient of numerous honorary degrees and awards. He has written and lectured widely on linguistics, philosophy, intellectual history, contemporary issues, international affairs, and U.S. foreign policy. Among his more recent books are,New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind; On Nature and Language; The Essential Chomsky; Hopes and Prospects; Gaza in Crisis; How the World Works;9-11: Was There an Alternative; Making the Future: Occupations, Interventions, Empire, and Resistance; The Science of Language; Peace with Justice: Noam Chomsky in Australia; Power Systems; and On Western Terrorism: From Hiroshima to Drone Warfare (with Andre Vltchek). -

Politics Was Very Good

A SHORT HISTORY OF OUR TIME di-lem'ma, 1 di-lem'a; 2 di-lëm'a, n. 1. A necessary choice between equally undesirable alternatives; a per plexing predicament. 2, Logic. A syllogistic argument which presents an antagonist with two (or more) alter natives, but is equally conclusive against him, whichever alternative he chooses. [ < Gr. dilèmma, < di-, two, + lèmma, anything taken.]—dil"em-mat'ic, a. 146 pacifism and the ussr-a discussion 150 battle of the churches in italy, by anton ciliga 155 the socialist labor party, by nathan dershowitz 159 european letter, by nicola chiaromonte 162 an american death camp, by harold orlansky 168 can we cure mental care? by elsie cronhimer 171 ancestors No. 6 - kurt tucholsky: (1) the man with the five pseudonyms, by hans sahl, (2) tucholsky's "testament", (3) herr wendriner under the dictatorship 178 the Wallace cam paign, an autopsy by dwight macdonald 189 commonnonsense, by niccolo tucci 189 remarks on the constitution of the mongolian people's republic, by theodore dryden 191 mr. sindlinger's option on the future, by harvey swados 194 amg in germany, by peter blake 202 the case of the dizzy dean at illinois university 203 on the elections, by dwight macdonald 206 report on packages-to-europe, by nancy macdonald 75c • No. 3,1948 Pacifism and the USSR A DISCUSSION Sir: tical disinterestedness which may at present enable you peacefully to withstand attacks by depraved, demented or May a recent reader comment briefly on what appears sadistic assailants, what would be your attitude if your to be an anomalous situation: the inclusion of the “ Peace wife and children were so threatened? Are you your makers” declaration, signed by the editor, in the very “brother’s keeper,” especially if he is your very own and issue devoted to “ USSR” — i. -

Gaza in Crisis : Reflections on the Us-Israeli War Against the Palestinians Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GAZA IN CRISIS : REFLECTIONS ON THE US-ISRAELI WAR AGAINST THE PALESTINIANS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Noam Chomsky | 288 pages | 03 Dec 2013 | Haymarket Books | 9781608463312 | English | Chicago, United States Gaza in Crisis : Reflections on the US-Israeli War Against the Palestinians PDF Book The Spymaster of Baghdad. The main obstacle to realizing these goals and targets is the colonial military occupation that continues to abolish all means of development in Palestine, in addition to ongoing land confiscation, continuous looting of Palestinians financial and natural resources, West Bank fragmentation due to settler expansion and the Gaza Strip blockade. I've read plenty of Chomsky but the Pappe articles are the strongest in here. Philippe Sands. The discovery of oil in the Middle East by five American oil companies, nicknamed the Five Sisters , resulted in a military— industrial nexus influential within the Republican Party with a pro-Arab stance, which has been largely sidelined by the Christian Zionists. Any suggestion of daylight between Israel and the U. In this interview, conducted by Frank Barat in , Chomsky highlights possible outcomes of the Palestine situation, the use of boycott and divestment and the important role that the U. I should say again that this book is important for everyone to read, especially the Western people since most of what they read regarding this matter is not the truth. Publishers Weekly describes the book as a, "succinct and eye-opening collection of recent interviews and essays", and although, "much of the material collected here precedes Israel's recent military attack on a Gaza-bound international flotilla of embargo-breaking humanitarian aid," it "gives essential context to the crisis". -

Palestinian Conflict: UN Intervention’

Law Faculty School of International Studies Title: ‘Operation ‘Cast Lead’ as a demonstration of the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict: UN Intervention’. Thesis prior to obtaining a degree in International Studies with bilingual major in Foreign Trade Author: Mónica Trelles Muñoz Director: Dr. Esteban Segarra Cuenca, Ecuador 2014 1 DEDICATION To Adriana, On the faith that she grows up in a peaceful world; witnessing the ideal of the liberty of the Palestinian people come true. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To God, for the infinite blessings and their manifestations. To my brother Kaiser, for being the reason to move forward, for having always believed in me and for being the strength to face each challenge with cheer and optimism. To my mother Jannet, for being the best role model, for bringing me up in goodness and for supporting me unconditionally in every path of life. To Francisco, for being the best life partner, for demonstrating me his love in every circumstance, for his unparalleled support and patience. To Paúl, Johanna, Verónica, María del Carmen and Antonio for their personification of the concept of friendship, for holding me in the most complicated moments and sharing with me the best ones. I owe each one of them infinite words of gratitude and love. To my grandparents Laura and Manuel. To Enrique Santos, for having been the one who sowed interest in me for the Palestinian people. To Norma Aguirre, for her good will. To Esteban Segarra. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………………...2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………3 TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………….………………………………………………4 INDEX OF FIGURES AND TABLES………….…………………………………………………7 LIST OF ANNEXES..….………………………………………………………………………….8 ABSTRACT.………………………………………………………………………………………9 INTRODUCTION...………………………………………………………………………….…11 1. -

The Workers' Party Revisited by Betty Reid Mandell Associate Professor of Social Work

Bridgewater Review Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 12 Jul-1985 Cultural Commentary: The orW kers' Party Revisited Betty Reid Mandell Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation Mandell, Betty Reid (1985). Cultural Commentary: The orkW ers' Party Revisited. Bridgewater Review, 3(2), 23-25. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol3/iss2/12 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. CULTURAL COMMENTARY The Workers' Party Revisited by Betty Reid Mandell Associate Professor of Social Work your houses." In 1948 this small group of ers' Party, another on Harvey Swados' 1970 Though conservative politicians tend to radicals, called the Worker's Party, was novel Standing Fast as a portrayal of the portray socialism as a unified, monolithic placed on Attorney General Tom Clark's list Workers' Party, and the third on three force, its history as an American political of subversive organizations. In 1958 they journals which had their roots in the Work and ideological movement is, as Betty Man were removed from the list. Then they ers' Party: Politics, Dissent, and New Po dell reports. anything but unified. To under disbanded. litics. Invitations were sent to former Work standsomething ofthe issues with which the Twenty-six years later, on May 6-7, 1983, ers' Party activists, some friends, and some movement has struggled, a bit of back some of that small group and a few friends contributors to early issues of the journals. ground may be useful. reassembled at New York University'S Tam The invitation list was a story in itself, In 1929 the Communist League ofAmer iment Library for a Workers' Party/ Stand combining those who had stood fast in their ica (later to change its name to the Socialist ing Fast conference to reminisce about old radicalism and those who had turned to the Workers Party - SWP) was founded on times and to celebrate the acquisition by right.