Report from Sweden: the First State-Owned Internet Poker Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Game Date of Approval Comments Nevada Gaming Commission Approved Gambling Games Effective August 1, 2021

NEVADA GAMING COMMISSION APPROVED GAMBLING GAMES EFFECTIVE AUGUST 1, 2021 NAME OF GAME DATE OF APPROVAL COMMENTS 1 – 2 PAI GOW POKER 11/27/2007 (V OF PAI GOW POKER) 1 BET THREAT TEXAS HOLD'EM 9/25/2014 NEW GAME 1 OFF TIE BACCARAT 10/9/2018 2 – 5 – 7 POKER 4/7/2009 (V OF 3 – 5 – 7 POKER) 2 CARD POKER 11/19/2015 NEW GAME 2 CARD POKER - VERSION 2 2/2/2016 2 FACE BLACKJACK 10/18/2012 NEW GAME 2 FISTED POKER 21 5/1/2009 (V OF BLACKJACK) 2 TIGERS SUPER BONUS TIE BET 4/10/2012 (V OF BACCARAT) 2 WAY WINNER 1/27/2011 NEW GAME 2 WAY WINNER - COMMUNITY BONUS 6/6/2011 21 + 3 CLASSIC 9/27/2000 21 + 3 CLASSIC - VERSION 2 8/1/2014 21 + 3 CLASSIC - VERSION 3 8/5/2014 21 + 3 CLASSIC - VERSION 4 1/15/2019 21 + 3 PROGRESSIVE 1/24/2018 21 + 3 PROGRESSIVE - VERSION 2 11/13/2020 21 + 3 XTREME 1/19/1999 (V OF BLACKJACK) 21 + 3 XTREME - (PAYTABLE C) 2/23/2001 21 + 3 XTREME - (PAYTABLES D, E) 4/14/2004 21 + 3 XTREME - VERSION 3 1/13/2012 21 + 3 XTREME - VERSION 4 2/9/2012 21 + 3 XTREME - VERSION 5 3/6/2012 21 MADNESS 9/19/1996 21 MADNESS SIDE BET 4/1/1998 (V OF 21 MADNESS) 21 MAGIC 9/12/2011 (V OF BLACKJACK) 21 PAYS MORE 7/3/2012 (V OF BLACKJACK) 21 STUD 8/21/1997 NEW GAME 21 SUPERBUCKS 9/20/1994 (V OF 21) 211 POKER 7/3/2008 (V OF POKER) 24-7 BLACKJACK 4/15/2004 2G'$ 12/11/2019 2ND CHANCE BLACKJACK 6/19/2008 NEW GAME 2ND CHANCE BLACKJACK – VERSION 2 9/24/2008 2ND CHANCE BLACKJACK – VERSION 3 4/8/2010 3 CARD 6/24/2021 NEW GAME NAME OF GAME DATE OF APPROVAL COMMENTS 3 CARD BLITZ 8/22/2019 NEW GAME 3 CARD HOLD’EM 11/21/2008 NEW GAME 3 CARD HOLD’EM - VERSION 2 1/9/2009 -

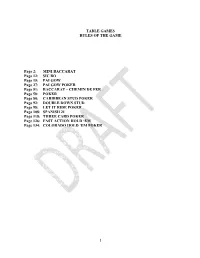

1 TABLE GAMES RULES of the GAME Page 2

TABLE GAMES RULES OF THE GAME Page 2: CRAPS AND MINI CRAPS Page 14: BLACKJACK Page 40: BACCARAT Page 50: BACCARAT – MIDI BACCARAT Page 59: ROULETTE AND BIG SIX WHEEL Page 65: RED DOG Page 2: MINI BACCARAT Page 12: SIC BO Page 15: PAI GOW Page 27: PAI GOW POKER Page 51: BACCARAT – CHEMIN DE FER Page 58: POKER Page 80: CARIBBEAN STUD POKER Page 92: DOUBLE DOWN STUD Page 98: LET IT RIDE POKER Page 108: SPANISH 21 Page 118: THREE CARD POKER Page 126: FAST ACTION HOLD ‘EM Page 134: COLORADO HOLD ‘EM POKER Page 213: BOSTON 5 STUD POKER Page 222: DOUBLE CROSS POKER Page 231: DOUBLE ATTACK BLACKJACK Page 241: FOUR CARD POKER Page 249: TEXAS HOLD ‘EM BONUS POKER Page 259: FLOP POKER Page 267: TWO CARD JOKER POKER Page 275: ASIA POKER Page 285: ULTIMATE TEXAS HOLD ‘EM Page 295: WINNER’S POT POKER Page 305: SUPREME PAI GOW Page 320: MISSISSIPPI STUD Page 328: CASINO WAR 1 7: MINIBACCARAT 1. Definitions The following words and terms, when used in this chapter, have the following meanings, unless the context clearly indicates otherwise: Dragon 7-- A Banker's Hand which has a Point Count of 7 with a total of three cards dealt and the Player's Hand which has a Point Count of less than 7. EZ Baccarat-- A variation of Minibaccarat in which vigorish is not collected. Natural-- A hand which has a Point Count of 8 or 9 on the first two cards dealt. Panda 8-- A Player's Hand which has a Point Count of 8 with a total of three cards dealt and the Banker's Hand which has a Point Count of less than 8. -

Code of Colorado Regulations

DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE Division of Gaming GAMING REGULATIONS 1 CCR 207-1 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] RULE 1 GENERAL RULES AND REGULATIONS BASIS AND PURPOSE FOR RULE 1 The purpose of Rule 1 is to establish definitions of various terms used throughout the rules of the Colorado Limited Gaming Control Commission so that the rules can be uniformly applied and understood. The statutory basis for Rule 1 is found in sections 12-47.1-201, C.R.S., 12-47.1-203, C.R.S., and 12-47.1- 302, C.R.S. 47.1-101 Purpose and Statutory Authority. These Rules and Regulations are adopted by the Colorado Limited Gaming Control Commission governing the establishment and operation of limited gaming in Colorado pursuant to the authority provided by article 47.1, title 12, C.R.S. The Commission will, from time to time, promulgate, amend and repeal such regulations, consistent with the policy, objects and purposes of the Colorado Limited Gaming Act, as it may deem necessary or desirable in carrying out the policy and provisions of that Act. 47.1-102 Construction. Nothing contained in these regulations shall be so construed as to conflict with any provision of the Colorado Limited Gaming Act or of any other applicable statute. 47.1-103 Severability. If any provision of these regulations be held invalid, it shall not be construed to invalidate any of the other provisions of these regulations. 47.1-104 Authorized games. Limited gaming permitted pursuant to article 47.1 of title 12, C.R.S., shall include only the following games: blackjack (21); poker; slot machines; craps; and roulette. -

Name of Game Date of Approval Comments Nevada

NEVADA GAMING COMMISSION APPROVED GAMBLING GAMES EFFECTIVE AUGUST 1, 2012 NAME OF GAME DATE OF APPROVAL COMMENTS ABC BACCARAT SIDE BET 1/29/2010 ACE‑ROULES 5/22/1997 NEW GAME ACEY DEUCEY – 21 5/19/2010 ACTION HARD WAY CRAPS 3/8/2002 (V OF CRAPS) ACTION POKER 7/29/1993 NEW GAME ACTION ROULETTE 5/19/2006 ALPHABETIC ROULETTE 11/17/2011 NEW GAME ANTE UP 21 11/16/2006 NEW GAME ANTE UP 21 – VERSION 2 6/19/2007 ANTE UP 21- POKER BONUS 7/31/2008 AQUARIUS ROULETTE 4/10/1989 (V OF ROULETTE) ASIA POKER 7/24/2008 NEW GAME ASIA POKER – VERSION 2 10/2/2009 ASIAN FIVE CARD STUD POKER 1/1/1999 (V OF POKER) AUTOMATIC WIN 7/18/2003 (V OF BLACKJACK) BABE RUTH’S HOMERUN BLACKJACK 1/18/2005 (V OF BLACKJACK) BACCARAT & MINI BACCARAT NRS. 463.0152 BACCARAT DOUBLE WAR 3/20/2009 BACCARAT SIDE BET 5/11/1995 BACCARAT 21 12/14/2006 (V OF BACCARAT) BACK TO BACK ROULETTE 7/31/1997 BAD BEAT BACCARAT 2/10/2012 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK 7/31/2008 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK – VERSION 2 11/18/2008 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK – VERSION 3 6/11/2009 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK – VERSION 4 1/19/2010 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK PROGRESSIVE 2/11/2011 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK PROGRESSIVE - VERSION 2 9/15/2011 BAD BEAT BLACKJACK PROGRESSIVE - VERSION 3 11/10/2011 BAD BEAT PAI GOW POKER 3/8/2004 BAD BEAT STUD POKER 6/21/2012 NEW GAME BAD BEAT STUD POKER - VERSION 2 7/30/2012 BAHAMA BONUS 3/23/2000 NEW GAME BAR'BOOT 3/1/1964 NEW GAME BEAT THE BANKER NRS. -

Poker for Dummies

[EBOOK]GAMBLERS POKER FOR DUMMIES THE BEST GUIDE FOR WIN AT POKER ONLINE “TRY THIS METHOD ON PARTYPOKER and win lot of money” by Richard D. Harroch and Lou Krieger Foreword by Chris Moneymaker Winner of the 2003 World Series of ER About the Authws Lou Krieger learned poker at the tender age of 7, while standing at his father's side during the weekly Thursday night game held at the Krieger kitchen table in the bluecollar Brooklyn neighborhood where they lived. Lou played throughout high school and college and managed to keep his head above water only because the other players were so appallingly bad. But it wasn't until his first visit to Las Vegas that he took poker seriously, buying into a low-limit Seven Card Stud game where he managed - with a good deal of luck -to break even. "While playing stud," he recalls, "I noticed another game that looked eved more interesting. It was Texas Hold'em. "I watched the Hold'em game for about 30 minutes, and sat down to play. One hour and $100 later, I was hooked. I didn't mind losing. It was the first time 1 played, and I expected to lose. But I didn't like feeling like a dummy so I bought and studied every poker book I could find." "I studied; 1 played. I studied and played more. Before long I was winning reg- ularly, and I haven't had a losing year since I began keeping records." In the early 1990s Lou Krieger began writing a column called "On Strategy" for Card Player Magazine. -

The World's #1 Poker Manual

Poker: A Guaranteed Income for Life [ Next Page ] FRANK R. WALLACE THE WORLD'S #1 POKER MANUAL With nearly $2,000,000 worth of previous editions sold, Frank R. Wallace's POKER, A GUARANTEED INCOME FOR LIFE by using the ADVANCED CONCEPTS OF POKER is the best, the biggest, the most money-generating book about poker ever written. This 100,000-word manual gives you the 120 Advanced Concepts of Poker and shows you step-by- step how to apply these concepts to any level of action. http://www.neo-tech.com/poker/ (1 of 3)9/17/2004 12:12:10 PM Poker: A Guaranteed Income for Life Here are the topics of just twelve of the 120 money-winning Advanced Concepts: ● How to be an honest player who cannot lose at poker. ● How to increase your advantage so greatly that you can break most games at will. ● How to prevent games from breaking up. ● How to extract maximum money from all opponents. ● How to keep losers in the game. ● How to make winners quit. ● How to see unexposed cards without cheating. ● How to beat dishonest players and cheaters. ● How to lie and practice deceit. (Only in poker can you do that and remain a gentleman.) ● How to control the rules. ● How to jack up stakes. ● How to produce sloppy and careless attitudes in opponents. ● How to make good players disintegrate into poor players. http://www.neo-tech.com/poker/ (2 of 3)9/17/2004 12:12:10 PM Poker: A Guaranteed Income for Life ● How to manipulate opponents through distraction and hypnosis. -

Female Poker Players: an Analysis of Women’S Responses to Minority Situations

Female Poker Players: An Analysis of Women’s Responses to Minority Situations A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Sociology at The Colorado College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Christina R. Ford May 2012 On my honor, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment. Christina Ford May 2012 ABSTRACT The data for this thesis was collected from eight interviews and participant observation. Participant observation took place in league poker games in bars and restaurants and cash poker games and tournaments in casinos. Interviews were conducted with both players of the poker league and casino poker. Poker is a male dominated game and it is a leisure time activity, outside of the workforce and the private home. Individuals who participated in these poker games reproduced gender binaries by performing gender. Male poker players respond to and treat women different than men, and women who participate in the poker games are expected to perform specific, stereotypical female roles. The research has addressed how gender is performed not only in the workplace or in private homes, but also in leisure activities in the public sphere. The implications of this include the reproduction of poker as a male dominated game in a male dominated arena and the reproduction of female stereotypes. Though women have been accepted into this male dominated game in great numbers, the men still treat women as though they do not belong. The females who participate in these poker games have extended the intentions of the feminist movement by seeking for equality of women in public arenas. -

![1 TEMPORARY RULEMAKING PENNSYLVANIA GAMING CONTROL BOARD [58 PA.CODE CHS. 521, 527, 553, 555, 557, 559, 561, 563 and 565] Tempor](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3583/1-temporary-rulemaking-pennsylvania-gaming-control-board-58-pa-code-chs-521-527-553-555-557-559-561-563-and-565-tempor-8073583.webp)

1 TEMPORARY RULEMAKING PENNSYLVANIA GAMING CONTROL BOARD [58 PA.CODE CHS. 521, 527, 553, 555, 557, 559, 561, 563 and 565] Tempor

TEMPORARY RULEMAKING PENNSYLVANIA GAMING CONTROL BOARD [58 PA.CODE CHS. 521, 527, 553, 555, 557, 559, 561, 563 and 565] Temporary Table Game Training Requirements; Temporary Table Game Rules for Poker, Caribbean Stud Poker, Four Card Poker, Let It Ride Poker, Pai Gow Poker, Texas Hold ‘em Bonus Poker and Three Card Poker The Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board (Board), under its general authority in § 1303A (relating to temporary table game regulations) enacted by the act of January 7, 2010 (Act 1) and the specific authority in §§ 1302A(1), (2), (3), (4), (5.1) and (7) and 1323A (relating to regulatory authority; and training of employees and potential employees) of Act 1, adopts temporary regulation Chapters 521, 527, 553, 555, 557, 559, 561, 563 and 565 to read as set forth in Annex A. The Board’s temporary regulations will be added to Part VII (relating to Gaming Control Board) as part of a new Subpart K entitled Table Games. Purpose of the Temporary Rulemaking This temporary rulemaking contains minimum training provisions for dealers, procedures to request permission to offer a new table game or seek a waiver of table game regulations and the rules for conducting the games of Poker, Caribbean Stud Poker, Four Card Poker, Let It Ride Poker, Pai Gow Poker, Texas Hold ‘em Bonus Poker and Three Card Poker. Explanation of Chapters 521, 527, 553, 555, 557, 559, 561, 563 and 565 In Chapter 521 (relating to general provisions), definitions of the terms “ante,” “cover card” and “stub” have been added. These terms are used throughout the chapters related to the rules of the games. -

VA Casinoemerregs

TITLE 11 – Gaming Agency 5 – Virginia Lottery Board 11VAC5-90 – Casino Gaming 10 Definitions 20 Unclaimed Jackpots 30 Waiver Request 40 Licenses and Permits Generally 50 Investigations 60 Applications for and Issuance of Facility Operator’s License 70 Applications for and Issuance of Supplier Permits 80 Applications for and Issuance of Service Permits 90 Enforcement 100 General Facility Operator Requirements 110 Casino Gaming Facility Minimum Internal Control Standards 120 Casino Gaming Facility Standards 130 On-premises Mobile Casino Gaming 140 Transportation and Testing of Gaming Machines and Equipment 150 Slot Machines 160 Mechanical Casino Games 170 Table Games Definitions and Equipment 180 Table Games Procedures TITLE 11 – Gaming Agency 5 – Virginia Lottery Board 11VAC5-90 – Casino Gaming 11 VAC 5-90-10 Definitions The following words and terms, when used in this chapter, shall have the following meanings unless the context clearly indicates otherwise. “Adjusted gross receipts" means the gross receipts from casino gaming less winnings paid to winners. “Administrative process act” means Chapter 40 (§ 2.2-4000 et seq.) of Title 2.2 of the Code of Virginia. February 3, 2021 1 “Applicant” means a person who has submitted an application to the board. “Application” means a written request for a license or permit that has been submitted to the board. “Associated equipment” means hardware located on a facility operator’s premises that is connected to the slot machine system for the purpose of performing communication, validation, or other functions, but not including the communication facilities of a regulated utility or the slot machines. “Average payout percentage” means the average percentage of money used by players to play a slot machine or mechanical casino game that is returned to players of that game. -

Poker for Dummies.Pdf

by Richard D. Harroch and Lou Krieger Foreword by Chris Moneymaker Winner of the 2003 World Series of ER About the Authws Lou Krieger learned poker at the tender age of 7, while standing at his father's side during the weekly Thursday night game held at the Krieger kitchen table in the bluecollar Brooklyn neighborhood where they lived. Lou played throughout high school and college and managed to keep his head above water only because the other players were so appallingly bad. But it wasn't until his first visit to Las Vegas that he took poker seriously, buying into a low-limit Seven Card Stud game where he managed - with a good deal of luck -to break even. "While playing stud," he recalls, "I noticed another game that looked eved more interesting. It was Texas Hold'em. "I watched the Hold'em game for about 30 minutes, and sat down to play. One hour and $100 later, I was hooked. I didn't mind losing. It was the first time 1 played, and I expected to lose. But I didn't like feeling like a dummy so I bought and studied every poker book I could find." "I studied; 1 played. I studied and played more. Before long I was winning reg- ularly, and I haven't had a losing year since I began keeping records." In the early 1990s Lou Krieger began writing a column called "On Strategy" for Card Player Magazine. He has also written two books about poker, Hold'em Excellence: From Beginner to Winner and MORE Hold'em Excellence: A Winner For Life. -

South Dakota Commission on Gaming Manual (PDF)

ARTICLE 20:18 GAMING COMMISSION -- DEADWOOD GAMBLING Chapter 20:18:01 General provisions. 20:18:02 Powers of commission. 20:18:03 Powers of executive secretary. 20:18:04 Declaratory rulings. 20:18:05 Promulgation of rules, Repealed. 20:18:06 Applications and fees. 20:18:07 Application approval. 20:18:07.01 Suitability procedure. 20:18:08 Enforcement. 20:18:08.01 Exclusion list. 20:18:09 Grounds for disciplinary action. 20:18:10 Disciplinary proceedings. 20:18:11 Contested cases. 20:18:12 Summary suspension procedure. 20:18:12.01 Operation of gaming establishments. 20:18:13 Integrity of equipment. 20:18:14 Authorized games. 20:18:14.01 Tournaments. 20:18:15 Blackjack. 20:18:16 Poker. 20:18:17 Slot machine requirements. 20:18:18 Slot machine testing, approval, and modifications. 20:18:18.01 Slot machine manufacturers. 20:18:18.02 Storing, displaying, and transporting slot machines. 20:18:19 Gaming equipment. 20:18:20 Chips, tokens, and tickets. 20:18:20.01 Cashier's cage. 20:18:20.02 Promotional items. 20:18:21 Operation of gaming establishments, Transferred or Repealed. 20:18:22 Accounting regulations. 20:18:23 Suitability and unsuitability procedure, Transferred. 20:18:24 Exclusion list, Transferred. 20:18:25 Building regulations. 20:18:26 Foreclosures. 20:18:27 Gaming compact with recognized Indian tribes. 20:18:28 Storing, displaying, and transporting slot machines, Transferred. 20:18:29 Security and surveillance. 20:18:30 Publicly traded corporations. 20:18:31 Gaming property owners. 20:18:32 Keno. 20:18:33 Craps. -

Casino Table Games Managers in Their Own Words

UNLV Gaming Press Books UNLV Libraries 2016 Tales from the Pit: Casino Table Games Managers in Their Own Words David Schwartz University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/gaming_press Part of the Gaming and Casino Operations Management Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, David, "Tales from the Pit: Casino Table Games Managers in Their Own Words" (2016). UNLV Gaming Press Books. 2. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/gaming_press/2 This Book is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Book in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Book has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Gaming Press Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Excerpts from Tales from the Pit They told me that if you were a dice dealer, you could have a job for the rest of your life, which still pretty much holds true today. We’re always looking for good dice dealers. Dave Torres And I wore glasses, I looked like a little school teacher...and it took me a good year and a half before I totally felt comfortable, and if someone called me a name or became argumentative or took a shot or anything like that, I would keep my mouth shut and deal my game.