Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychedelics: Unp Acked

W I N T E R 2 0 2 0 : V O L U M E 1 S O C I E T Y A N D G E N E T I C S PSYCHEDELICS: UNPACKED IS PSILOCYBIN A T H E WHAT IS VIABLE MEDICAL PSILOCYBIN'S PATH TREATMENT? I S S U E S TO LEGALIZATION? Find out on page 4! Find out on page 28! R E A D Y TRIP? F O R Y O U R 2 Editor's Note 4 Is Psilocybin a Viable Medical Treatment? THE SCIENCE 14 Neuroscience of Depression and Anxiety 18 Antidepressants: A Current Analysis THE HISTORY 20 Psychedelics; Neuroscience of the Brain Part 1: The Shamanic 24 Part 2: The Science/Political 26 What is Psilocybin's Path to 28 Legalization? THE SOCIAL/CULTURAL 35 Unpacking Recreational Psychedelic Culture 36 How Psychedelics Have Influenced the Mainstream 01 PSYCHADELICS: UNPACKED LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Dear Distinguished Reader, By association with the countercultural When you hear the word psychedelics, it is likely that strong preconceptions will come to mind. Terms like communities that threatened the status quo, “drug,” “addict,” and “illegal” may spring to the forefront. Or psychedelics came to represent a threat to the maybe “trip,” “hallucinations” and “adventure” do. But dominant narrative, and thus have been painted as what about words like “medicine” or “treatment?” The idea dangerous. LSD was linked to addiction through of using psychedelics as potential treatment for mental mass manipulation by the government demanding illness was actually tested as early as the 1950s (Read colleges to report any activities and findings more about this history on page 26), and promising results associated with the drug. -

Qanon • 75 Years of the Bomb • Vaccine History • Raising

SQANON • K75 YEARS OF ETHE BOMB P• VACCINE HISTORYT • RAISINGI CTHE DEAD? Extraordinary Claims, Revolutionary Ideas & the Promotion of Science—Vol.25Science—Vol.25 No.4No.4 2020 $6.95 USA and Canada www.skeptic.com • WHAT IS QANON? • HOW QANON RECYCLES CENTURIES-OLD CONSPIRACY BELIEFS • HOW QANON HURTS THEIR OWN CAUSE • QANON IN CONSPIRATORIAL CONTEXT watch or listen for free Hear leading scientists, scholars, and thinkers discuss the most important issues of our time. Hosted by Michael Shermer. #146 Dr. DonalD Prothero— # 130 Dr. DeBra Soh—the end # 113 Dave ruBIn— # 106 Dr. DanIel ChIrot— Weird earth: Debunking Strange of Gender: Debunking the Myths Don’t Burn this Book: you Say you Want a revolution? Ideas about our Planet about Sex & Identity in our Society thinking for yourself in an radical Idealism and its tragic age of unreason Consequences #145 GreG lukIanoff—Mighty # 129 Dr. Mona Sue WeISSMark Ira: the aClu’s controversial involve- —the Science of Diversity # 112 ann Druyan—Cosmos: # 105 Dr. DIana PaSulka— ment in the Skokie case of 1977. Possible Worlds. how science and american Cosmic: ufos, # 128 MIChael ShellenBerGer civilization grew up together religion, and technology #144 Dr. aGuStIn fuenteS— —apocalypse never: Why environ- Why We Believe: evolution and the mental alarmism hurts us all human Way of Being # 127 Dr. WIllIaM Perry and #143 Dr. nICholaS ChrIStakIS— toM CollIna—the Button: the apollo’s arrow: the Profound and new nuclear arms race and Presi- enduring Impact of Coronavirus on dential Power from truman to trump the Way We live # 126 Sarah SColeS—they are #142 Dr. -

Korištenje Velikih Podataka U Filmskoj Industriji Na Primjeru Netflix-A

Korištenje velikih podataka u filmskoj industriji na primjeru Netflix-a Bilać, Anđela Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Economics and Business / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Ekonomski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:148:761421 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-02 Repository / Repozitorij: REPEFZG - Digital Repository - Faculty of Economcs & Business Zagreb Sveučilište u Zagrebu Ekonomski fakultet Menadžerska informatika KORIŠTENJE VELIKIH PODATAKA U FILMSKOJ INDUSTRIJI NA PRIMJERU NETFLIX-A DIPLOMSKI RAD Anđela Bilać ZAGREB, RUJAN, 2020. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Ekonomski fakultet Menadžerska informatika UPORABA VELIKIH PODATAKA U FILMSKOJ INDUSTRIJI NA PRIMJERU NETFLIX-A USING BIG DATA IN MOVIE INDUSTRY ON EXAMPLE OF NETFLIX Diplomski rad Anđela Bilać, 0067509307 Mentor: Prof. dr. sc. Mirjana Pejić Bach ZAGREB, RUJAN, 2020. Sažetak Svrha ovog rada je utvrditi koriste li osobe u Republici Hrvatskoj streaming servise. Također, istraživanjem će se ispitati stavovi pojedinaca o streaming servisima, te navike tijekom gledanja sadržaja. Isto tako, istražiti će se učestalost korištenja streaming servisa i predviđanja ispitanika o budućnosti ovakvog oblika pružanja usluga gledanja određenog sadržaja. Istraživanje je provedeno Internet anketnim upitnikom na uzorku od 253 osobe. Analizom istraživanja utvrdilo se da su ljudi u velikoj mjeri upoznati sa streaming servisima i da koriste njihove usluge za gledanje sadržaja. Način gledanja sadržaja se poklapa s tvrdnjama iznesenim u teorijskom dijelu rada. A to je da se ovakve usluge koriste većinom za gledanje serija, i da se najćeše gleda više epizoda odjednom. Istraživanje je pokazalo da je najveća prednost servisa njihova dostupnost i lakoća korištenja, a najveći nedostatak potreba korištenja interneta za konzumiranje sadržaja i visoka cijena. -

Great Awakening 2020: the Neoliberal Wellness Journey Down the Rabbit Hole

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 8-2021 GREAT AWAKENING 2020: THE NEOLIBERAL WELLNESS JOURNEY DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE Melissa Ann McLaughlin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation McLaughlin, Melissa Ann, "GREAT AWAKENING 2020: THE NEOLIBERAL WELLNESS JOURNEY DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE" (2021). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1277. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GREAT AWAKENING 2020 THE NEOLIBERAL WELLNESS JOURNEY DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Melissa McLaughlin August 2021 GREAT AWAKENING 2020 THE NEOLIBERAL WELLNESS JOURNEY DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Melissa McLaughlin August 2021 Approved by: Kevin Grisham, Committee Chair, Geography Hareem Khan, Anthropology © 2021 Melissa McLaughlin ABSTRACT 2020 was a good year for conspiracy theory. From COVID denialism to QAnon, the usual cast of conspiracy influencers was joined by mommy bloggers, yoga teachers, and social media opportunists to spread disinformation and sow doubt in the American psyche across the vast network of the internet. -

Sunday-Times-Article.Pdf

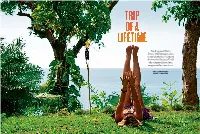

TRIP OF A LIFETIME Nothing could help Decca Aitkenhead process her grief after her husband drowned in Jamaica. Until she returned there for a magic mushroom retreat PHOTOGRAPHS BY ABBIE TOWNSEND have never felt so sick, abandoned or attention is drawn to an antique silver INNER VISIONS PARADISE FOUND terminally alone. A dragging sickness case on the sideboard, which we were Left: One of the Below, top: the in my stomach grows insistent, told contains a limitless supply of spliffs MycoMeditations resort’s idyllic until the nausea is worse than hand-rolled at dawn every day by the “facilitators”, Justin, surroundings. chemotherapy, morning sickness and butler. It all felt promisingly fun. I’d taken checks in with Bottom: guests food poisoning combined. Everything mushrooms recreationally years ago, and Decca during a trip enjoy fine dining around me has been draped in a had a hoot; the promise of a deeper psychic ghostly white sheer netting, cleanse this time is thrilling. transforming this beautiful lush The following day, holding a plastic tub of recklessly “high-risk rave”. Eric had to go on tropical garden into Miss Havisham’s fat grey capsules, each containing 0.5g of national TV to try to reassure Jamaicans attic. Wherever I turn, everything is ugly, psilocybin, the retreat director, Eric that psilocybin poses no long-term threat Ideathly and hostile. I’d always wondered Osborne, goes round the circle calculating to mental health. His views are backed by what a bad psychedelic trip would be like. our optimal starter doses according to body scientists at Johns Hopkins who, in 2018, An hour ago I took 9g of psilocybin, and size, drug experience and emotional stated that “psilocybin is one of the least now I know. -

The Clarion, Vol. 85, Issue #19, Feb. 5, 2020

Chloe’s crash clarion.brevard.edu course on page 6! Volume 85, Issue 19 Web Edition SERVING BREVARD COLLEGE SINCE 1935 February 5, 2020 Oscar 2020 nominations By Zach Dickerson The film essentially represents the basic and This film, in a way, transcends to be more Editor in Chief stereotypical set up of the basic conventional than just a comic book movie and almost acts While there are many worthy and prestigious sports film setup and plot. Miles is the maverick as a character study and holds up a mirror to awards that are given out at the Oscars by the driver wanting to push the car and himself to society, but the added DC Comics elements Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the limit to be the best, and Shellby is stuck in make it more entertaining and interesting for the most coveted and sought after of all the middle trying to appease the people at Ford fans. The film does an amazing job of making these awards is the Academy Award for Best and control Miles. This, in a way, makes the film the Joker as realistic as possible by combining Picture. All of the films that are nominated are somewhat predictable and at times the audience mental health and the treatment from society as fascinating, interesting and very deserving of can lose interest. justifiable reasoning for why Fleck does what the awards they are nominated for. The films But the racing and car scenes are shot he does and why he becomes what he becomes. that are nominated are: amazingly and give the feel of really being At times the film can be intense and very “1917” directed by Sam Mendes (Dec. -

Bioethical Deliberations Can They Save Us and Our Planet?

Contemporary Bioethical Deliberations Can They Save Us and Our Planet? LLC—Wednesdays—10 AM to Noon ON ZOOM Frank Schaberg Ruth Levy Guyer [email protected] [email protected] Course description What can individuals do to ensure that advances in medicine, science and technology promote good outcomes rather than destructive ones? What medical advances are changing our understanding of patients’ rights, including a patient’s right to try unproven drugs and treatments and the right to die with dignity? And what about the rights and responsibilities of healthcare workers? How can patients protect themselves from charlatans and scam artists? How has climate change already damaged human health, the wellbeing of plants and animals and ecosystems? What scientific advances are altering our understanding of gender, identity, and the rights of future generations? What are the effects of unending war on human behavior and health and the balance in nature? We will focus on case studies—real stories—that illustrate these and other contemporary concerns. We will consider where the responsibilities lie with individuals, communities, governments, and international organizations, both for having created current problems and now for solving them. We will consider how ethical principles can clarify our thinking and help with problem solving. Class 1 IN PERSON!!! INTRODUCTIONS Hour 1: Introduction of members of class; introduction to the course Hour 2: The case-study method and two illustrative cases Class 2 ZOOM CLASS—DIVIDED BETWEEN TWO WEEKS AUTONOMY RESPECTED AND DENIED In order to live lives of dignity, individuals must have the right to make their own informed decisions. -

Top 5 Natural Health Remedies of 2021, So Far

Top 5 Natural Health Remedies of 2021, So Far Healthy living is always important. In light of recent events, there is more of a push for us to take care of our health and well-being. Natural health remedies are more popular than ever. A-list celebrities such as Gwyneth Paltrow advocate healthy living and natural health remedies rather than pharmaceuticals. She even has her own Netflix series, called the Goop Lab, featuring her own company and her journey towards caring for her body, naturally. Cannabis & CBD Cannabis and CBD are the most talked-about natural remedies of 2021. It’s inconceivable that cannabis was once a hugely taboo subject. The acceptance of cannabis has encouraged the industry to create and sell a variety of products. Whether you’re interested in hybrid seeds or pure strains of Indica or Sativa, it’s important to do your research to find the one that will best serve you as a health remedy. As a rule, hybrid strains are more beneficial as health remedies because both strains are combined. Therefore, users have the best of both worlds. Here are some of the things that cannabis can alleviate the symptoms of: Glaucoma ADHD/ADD Anxiety and depression Seizures Pain Inflammation Insomnia Weight loss The list could go on. As long as cannabis is consumed in moderation and under the guidance of a specialist, it can work wonders. CBD stands for cannabidiol. It’s a naturally occurring substance derived from the Sativa strain. CBD treats the following conditions, just without the added high that recreational cannabis users enjoy: Anxiety and stress Inflammation Insomnia Acne Chronic pain Drug addictions Currently, 1 in 7 Americans is dipping their toes into CBD waters and reaping the benefits. -

The Online Wellness Industry: Why It’S So Difficult to Regulate

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Baker, S.A. ORCID: 0000-0002-4921-2456 and Rojek, C. (2020). The online wellness industry: why it’s so difficult to regulate. The Conversation, This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/24055/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 4/18/2020 The online wellness industry: why it's so difficult to regulate Make sense of the news. Read our experts in your inbox. Get the newsletter Academic rigour, journalistic flair Netflix The online wellness industry: why it’s so difficult to regulate February 20, 2020 8.51am GMT Netflix recently released Gwyneth Paltrow’s new six-part series, The Goop Lab. Each Authors episode explores an area of the wellness industry, including psychedelics, cold therapy, lifestyle interventions, female pleasure and sexual healing. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Literature in the Age Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Literature in the Age of Wellness DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English Literature by Jacob William Baumgartner Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Theodore Martin, Chair Assistant Professor Christopher Fan Professor Daniel M. Gross Associate Professor Allison Perlman 2021 © 2021 Jacob William Baumgartner DEDICATION To my Dad Mark William Baumgartner ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv VITA v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Office Novel and Workplace Wellness Programs 28 CHAPTER 2: The Millennial Novel and Wellness Without Work 71 CHAPTER 3: The Dystopian Novel and Wellness at the End of the World 121 CONCLUSION 165 BIBLIOGRAPHY 167 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Dr. Theodore Martin for his support, patience, and guidance throughout this process. I would also like to thank my committee members Dr. Christopher Fan, Dr. Daniel Gross, and Dr. Allison Perlman for volunteering their time and energy and for supporting me throughout my time here at UCI. Finally, thank you to Dr. Rodrigo Lazo for being such a generous mentor during my first years in the program. It has been an honor and a privilege to work with all of you, and I am grateful for having had the opportunity to do so. I would be remiss not to include my heartfelt gratitude to the English department at Orange Coast College. No matter how many times I was on academic probation (twice, last I counted) or failed to show up for class, you never wavered in your support and continued to believe in my potential. -

Theorizing #Girlboss Culture: Mediated Neoliberal Feminisms from Influencers to Multi-Level Marketing Schemes

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2021 Theorizing #Girlboss Culture: Mediated Neoliberal Feminisms from Influencers ot Multi-level Marketing Schemes Frankie Mastrangelo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political Theory Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Rhetoric Commons, Social Justice Commons, Social Media Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Visual Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6648 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Theorizing #Girlboss Culture: Mediated Neoliberal Feminisms from Influencers to Multi-level Marketing Schemes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University by Frankie Mastrangelo Master of Arts, Media, Cinema, and Digital Studies, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee 2016 Bachelor of Arts, English and Women’s Studies, Rollins College, 2010 Director: David Golumbia, Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia Copyright Frankie Mastrangelo 2021 All Rights Reserved 2 Acknowledgements Thank you to my committee advisors: David Golumbia, Jesse Goldstein, Karen Rader, Myrl Beam, and Jenny Rhee. -

Gwyneth Paltrow's the Goop Lab Whitewashes Traditional Health Therapies for Profit

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Business and Law - Papers Faculty of Business and Law 1-1-2020 Marketing, not medicine: Gwyneth Paltrow's The Goop Lab whitewashes traditional health therapies for profit Nadia Zainuddin University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/balpapers Recommended Citation Zainuddin, Nadia, "Marketing, not medicine: Gwyneth Paltrow's The Goop Lab whitewashes traditional health therapies for profit" (2020). Faculty of Business and Law - Papers. 41. https://ro.uow.edu.au/balpapers/41 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Marketing, not medicine: Gwyneth Paltrow's The Goop Lab whitewashes traditional health therapies for profit Abstract In Gwyneth Paltrow's new Netflix series, The Goop Lab, Paltrow explores a variety of wellness management approaches, from "energy healing" to psychedelic psychotherapy. Goop has long been criticised for making unsubstantiated health claims and advancing pseudoscience, but the brand is incredibly popular. It was valued at over US$250 million (A$370 million) in 2019. Publication Details Zainuddin, N. (2020). Marketing, not medicine: Gwyneth Paltrow's The Goop Lab whitewashes traditional health therapies for profit. The Conversation, 29 January 1-5. This journal article is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/balpapers/41 Marketing, not medicine: Gwyneth Paltrow’s The Goop Lab whitewashes... https://theconversation.com/marketing-not-medicine-gwyneth-paltrows-t... Academic rigour, journalistic flair Netflix’s new show fails to critically explore the alternative therapies it promotes.