Scheduled Monument Consent Heritage and Design Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peak Forest Canal, Marple to Whaley Bridge Easy: Please Be Aware That the Grading of This Trail Was Set According to Normal Water Levels and Conditions

Peak Forest Canal, Marple to Whaley Bridge Easy: Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Distance: 6½ Miles. Approximate Time: 1-3 Hours The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Type of Trail: One Way Waterways Travelled: Peak Forest Canal Type of Water: Urban and rural canal. Portages and Locks: None Vehicle Shuttle is required Nearest Town: Marple, Disley, and Whaley Bridge Route Summary Start: Lockside, Marple, SK6 6BN Finish: Whaley Bridge SK23 7LS The Peak Forest Canal was completed in 1800 except for O.S. Sheets: OS Landranger Map 109 Manchester, Map the flight of locks at Marple which were completed four 110 Sheffield & Huddersfield. years later to transport lime and grit stone from the Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle on quarries at Dove Holes to industrial Manchester and this waterway. See full details in useful information below. beyond. It was constructed on two levels and goes from the junction with the Macclesfield Canal at Marple six and Local Facilities: There are lots of facilities in the towns a-half-miles to the termini at Whaley Bridge or Buxworth. and villages that lie along the canal including an excellent At 518 feet above sea level it’s the highest stretch of fish and chip shop close to the terminus at Whaley Bridge. -

Parish Council Guide for Residents

CHAPEL-EN-LE-FRITH PARISH WELCOME PACK TITLE www.chapel-en-le-frithparishcouncil.gov.uk PARISH COUNCILGUIDE FOR RESIDENTS Contents Introduction The Story of Chapel-en-le-Frith 1 - 2 Local MP, County & Villages & Hamlets in the Parish 3 Borough Councillors 14 Lots to Do and See 4-5 Parish Councillors 15 Annual Events 6-7 Town Hall 16 Eating Out 8 Thinking of Starting a Business 17 Town Facilities 9-11 Chapel-en-le-Frith Street Map 18 Community Groups 12 - 13 Village and Hamlet Street Maps 19 - 20 Public Transport 13 Notes CHAPEL-EN-LE-FRITH PARISH WELCOME PACK INTRODUCTION Dear Resident or Future Resident, welcome to the Parish of Chapel-en-le-Frith. In this pack you should find sufficient information to enable you to settle into the area, find out about the facilities on offer, and details of many of the clubs and societies. If specific information about your particular interest or need is not shown, then pop into the Town Hall Information Point and ask there. If they don't know the answer, they usually know someone who does! The Parish Council produces a quarterly Newsletter which is available from the Town Hall or the Post Office. Chapel is a small friendly town with a long history, in a beautiful location, almost surrounded by the Peak District National Park. It's about 800 feet above sea level, and its neighbour, Dove Holes, is about 1000 feet above, so while the weather can be sometimes wild, on good days its situation is magnificent. The Parish Council takes pride in maintaining the facilities it directly controls, and ensures that as far as possible, the other Councils who provide many of the local services - High Peak Borough Council (HPBC) and Derbyshire County Council (DCC) also serve the area well. -

A Day out in Marple Starts Here

A Vision for Marple A Presentation to Stockport MBC by Marple Civic Society January 2010 2 CONTENTS Page Introduction …………………………………………………………….. 3 Area covered by report ………………………………………………… 5 Canals • Marple Wharf – Brickbridge ………………………………………. 6 • Marple Wharf – Aqueduct …………………………………………. 8 • Marple Wharf - Goyt Mill …………………………………………..13 Marple Wharf ……………………………………………………………..14 Conclusions ……………………………………………………………….17 Next steps ………………………………………………………………….17 Appendix 1 - Acknowledgements Appendix 2 - Summary of objections and ideas for Marple Wharf from members of the community Marple Civic Society – January 2010 3 INTRODUCTION As the Visit Marple pamphlet prepared by the Marple Business Forum so rightly says: “Increasingly, Marple is attracting visitors from a wider area, drawn by the colourful array of canal boats, opportunities for countryside walks and the thriving shopping centre. What other town in the region has more to offer than Marple? We cannot think of one that can boast two railway stations, its own theatre, a cinema, swimming pool, bustling pubs, café bars and restaurants (and even two brass bands). Add to that its countryside setting (5,000 of Marple’s 7,000 acres are in the Green Belt), the network of picturesque canals and its huge variety of independent shops and we believe we have something special to shout about.” However, the Marple Civic Society and many other local stakeholders and members of the community believe that Marple could and should be improved even further. Many places of interest in Marple are under-exploited and need developing for tourism, recreation and community purposes. The town was very much shaped by 18th century entrepreneurs Samuel Oldknow and Richard Arkwright. During this time Oldknow changed the face of Marple beyond all recognition, being the chief architect and driving force in the development and industrialisation of the area. -

Marple Locks & the Upper Peak Forest Canal. Management Plan 2015

Marple Locks & The Upper Peak Forest Canal. Management Plan 2015 - 2017 David Baldacchino Waterway Manager Manchester and Pennines Rev 5: 29th February 2016 Management Plan for Marple and the Upper Peak Forest Canal Contents. Page 1 Objective 1 2 Audience 1 3 Structure 1 4 Scope 3 5 Marple and the Upper Peak Forest Canal 4 6 The organisation 9 7 Vision and Values 10 8 Budget and planning process 11 9 Asset Management 12 10 Heritage Management 15 11 Environmental Management. 21 12 Environmental protection 26 13 Water resources Management 28 14 Safety, security and incident management 30 15 Visitors and users 32 16 Development & Community engagement 37 17 Summary of Key Plan Targets 2015 -2017 40 Appendices A Organisational Structure (a) Regional 42 (b) National 43 Key Contracts 44 C Key Stakeholders 45 D Revealing Oldknow’s Legacy – Project Information 46 Management Plan for Marple Locks and the Upper Peak Forest Canal 1. Objective This plan has been prepared to give all stakeholders a clear overview of how the Upper Peak Forest Canal is currently managed and our priorities for the future. It describes:- The physical infrastructure. The organisation in place to manage aspects of the canal, and achieve our aims and objectives. Our objectives and operating principles. The management systems in place to maintain and enhance the network. Baseline data on its condition and usage. Key Performance Indicators and measures of success. Identified ‘Plan Targets’ that we hope to deliver over the planning period. 2. Audience This plan has been written to address the needs of a number of stakeholders. -

AIA Bulletin 09-4 1982

gt ASSocrAroN FoR TNDUSTRTAL ArcFAEor-ocy B u [ il I n Volume9Number4lg92 Mainly on the subject of Bridges an iron bridge that required even the furnaces work were a 90 f oot arch rib at the Walker to be enlarged - and the erection of half ribs family ironworks at Rotherham, and a 100 or 110 weighing nearly six tons. foot trial span erected at the Yorkshire stingo Dwelopment in Early lron Bridges, The earliest The development of a design in iron for the (a pub) in Paddington. Paine's design was a substantial use of iron in bridges rests with the Severn span by Thomas Pritchard is now well series of short curved wrought iron bars, Chinese in suspension bridges of iron chains, with known, from a segrnental iron vault supporting separated vertically by cast iron connecting wooden decks laid directlv on the chains. One masonry to the multiribbed spandrel structure pieces, to form arch ribs of very low rise. Had is recorded as dating from the early days of the which is clearly represented in the existing Paine continued to press his ideas there is no Han dynasty (200 BC). However problematical briQge. Pritchard had the better engineering doubt that the course of iron bridge construction the documentation of such bridges in Asio some solution in a bridge of relatively low rise, but would have been radically different. H is con- of these structures - with as manv as twenty this was abandoned to provide the stone arch ceots were substantiallv more advanced than chains - certainly deserve the description of proportions or lronbridge giving clearance for those followed and his arch ribs only slightly 'iron bridges'. -

Chinley, Buxworth and Brownside Parish Statement (Draft)

Chinley, Buxworth and Brownside Parish Statement (draft) The parish of Chinley, Buxworth and Brownside is located at the western edge of the Dark Peak landscape area of the Peak District National Park. In terms of area, approximately half of the parish is within the National Park, although it is worth noting the majority of development and population of the parish are outside of the National Park boundary. Chinley and Buxworth are the main settlements which are located to the north of the A6 road, outside the National Park. Historically, Chinley was a Anglo-Saxon settlement of scattered farmsteads. During the 17th century the local area was mined and quarried and consequently Chinley’s population grew. These local industries developed further following the building of the Peak Forest Canal and tramway in 1799 and again when the railway came in 1866. The addition of a passenger line in 1894 saw further population growth. However, the closures of the mines and quarry in the early 20th century saw the population decline. It declined further following WWII when the passenger service was reduced, however in recent years there has been a significant amount of new housing development in proximity of the parish and the area has become a very popular commuting area. Further development is also anticipated soon. New businesses have opened recently in the food and beverage, accommodation and childcare sectors. The area is a popular walking, cycling and horse-riding area with the Peak Forest Tramway Trail and Bugsworth Basin also popular attractions. Source: thanks to Chinley, Buxworth and Brownside Parish Council The parish straddles three landscape character areas within the Dark Peak; valley pastures with industry, enclosed gritstone upland and moorland hills and ridge as described in the Landscape Strategy (LSAP 2009). -

Newsletter Autumn 2017 FINAL

Chinley, Buxworth and Autumn Brownside Parish Council 2017 Parish Room, 3 Lower Lane, Chinley, High Peak, Derbyshire, SK23 6BE Parish Clerk: Mrs Georgina Cooper [email protected] Tel: 01663 750139 www.chinleybuxworthbrownside-pc.gov.uk Welcome! Local Policing News Welcome to the Autumn edition of our parish newsletter. It’s been a Derbyshire’s Police and Crime busy few months with events at Bugsworth Basin and Chinley for all Commissioner Hardyal Dhindsa the family to enjoy and there’s plenty more coming up. Read on to has pledged to visit all 383 towns and villages find out more! during his term in office. He will be at As we move into Autumn we get closer to the potential for snow. Bookswap at Chinley Community Centre on Would you be willing to volunteer to clear snow, should it fall, from Wednesday 1st November at 10:30am. some of the vital pavements and footpaths within Please drop in to tell him your views on local our parish to help keep our villages moving? If so policing issues. we would like to hear from you! As a parish we On other policing matters an assault took have the opportunity to be involved in Derbyshire place in Chinley at 8pm on 31st August 2017. County Council’s FREE snow warden scheme. They provide the grit, An unknown offender shot the victim with an training, gloves and high-vis vests if we have some snow wardens on air weapon at the allotments on Lower Lane. standby. If you would like more information please get in touch. -

Blackbrook House Visitors Centre

BLACKBROOK HOUSE VISITORS CENTRE BUGSWORTH BASIN H I G H P E A K S K 2 3 7 N F PLANNING APPLICATION DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT OCTOBER 2009 1 1 6 1 BLACKBROOK HOUSE - BUXWORTH JOHN McCALL ARCHITECTS INTRODUCTION SCHEME DETAILS Site Location Bugsworth Basin, Buxworth, High Peak, Derbyshire SK23 7NE Development Relocation of the existing visitors centre from shipping containers into a dedicated new build facility, to be called Blackbrook House Visitors Centre, which will house and provide an improved interpretive exhibition about Bugsworth Basins history and heritage. Date. Prepared October 2009 Applicant British Waterways Waterside House, Waterside Drive, Wigan, WN3 5AZ Agent John McCall Architects, No1 Arts Village, Henry Street, Liverpool, L1 5BS Tel 0151 707 1818 Fax 0151 707 1819 [email protected] 2 1 1 6 1 JOHN McCALL ARCHITECTS The DESIGN Process ASSESSMENT Physical Situated at the head of the Peak Forest Canal, Bugsworth Basin comprises the largest and most complete surviving example of an inland transhipment port ever created on the English narrow canal network, which once extended to over three thousand miles of canals. The basin incorporates the terminal interchange between the Peak Forest Canal and its associated tramway and was once a thriving industrial centre for the transhipment of over six hundred tonnes of limestone, gritstone and lime per day - aswell as comprising a localised centre for the production of burnt lime. The Basin complex contains many structural and artifactual features that are almost, if not completely unique to the British Inland Waterways Network. The Peak Forest Tramway (the connecting flow lines of which traverse the entire Basin complex), opened in 1796, and was certainly one of the very early mineral railways to service a British Inland Waterways based transport system, and ranks amongst the earliest Derbyshire railways to have been fitted with iron rails. -

Industrial Archaeology Studies in England

Engineering Field Experience: Industrial Archaeology Studies in England Harriet Svec, Harvey Svec, Teresa Hall, William Martin Whalley South Dakota State University / Manchester Metropolitan University The practice of engineering could be described as a nascent profession when contrasted with medicine, law, academia, politics or the clergy. Engineering as a career emerged as recently as the 1800s as an outcome of newly created industry-based economies. Today the engineering profession is well established, respected, and contributes to the greater benefit of society. Bringing science, technology and creativity together, engineers conceive solutions to problems, develop new designs for products, and generate new wealth through the resultant economic activity derived from manufacturing, construction, medicine, agriculture or other industries. The variety of disciplines under the engineering descriptor continues to grow as technology becomes more advanced and complex, always looking to the future and the next new idea and its application. Yet, few students in engineering and related technology programs are given the opportunity to explore and gain understanding from the historical events upon which modern engineering practice was built. To this end, faculty members at South Dakota State University and Manchester Metropolitan University have collaborated to offer an Industrial Archaeology study abroad experience based out of Manchester England, the epicenter of modern engineering application: the Industrial Revolution. The Need for Engineering Archaeological Field Sites Natural science and social science disciplines such as biology, anthropology and archaeology have valued the traditional field site as significant to building the body of knowledge in their specialty. Faculty and students work together at these field sites to gather data, catalog artifacts or observations, and disseminate results through publications, presentations, and the curriculum. -

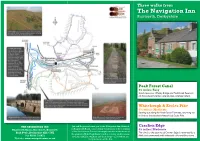

Navigation Inn V2

Three walks from The Navigation Inn Buxworth, Derbyshire Peak Forest Canal 2¾ miles: Easy Good views over Whaley Bridge and Toddbrook Reservoir on the outward journey, and an easy canalside return. Whitehough & Eccles Pike 3½ miles: Moderate Starting out along the Peak Forest Tramway, returning via a climb to the elevated viewpoint of Eccles Pike. THE NAVIGATION INN Jan and Roger welcome you to the Navigation Inn. Situated Cracken Edge Bugsworth Basin, Brookside, Buxworth on Bugsworth Basin, a once-busy canal basin at the terminus 4½ miles: Moderate of the Peak Forest Canal, this unique site lies in the heart of High Peak, Derbyshire SK23 7NE The climb to the quarries of Cracken Edge is rewarded by a the stunning High Peak District and is popular with boaters, Tel: 01663 732072 cyclists, families, walkers and their dogs – all of whom are high-level promenade with industrial relics and fine views. Website: www.navigationinn.co.uk very welcome at the Inn. turn right, uphill, and cross the A6. 5 Take the first right (Eccles interlude followed by a slight rise, when the path starts to descend Peak Forest Canal Terrace) and at the end follow the footpath up a driveway to the left. towards the isolated farmhouse of Whiterakes, look out for a bench by 2¾ miles: Easy When this swings right into the property, keep along the footpath the path dedicated to one Shirley Fidler. 16 Immediately beyond this ahead. 6 When you reach the road, turn left. 7 At a crossroads, take bench, leave the obvious path, heading obliquely left up the slope on May be muddy in places. -

Minutes, Full Council, 2014 06 26

Chinley, Buxworth and Brownside Parish Council Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Thursday 26th June 2014, 7.30pm at the Parish Office, 3 Lower Lane, Chinley Present: Councillors P Wilson (Chair) Mrs A Bramah, R O Drabble, Mrs A Phillips, Mrs C Rofer and W Smith. Clerk Mrs B Wise. County Councillor D Lomax. One member of the public. 14/06/37 Apologies for Absence Apologies for absence were received from Cllrs A Knox, Mrs J Pettitt, M Walton and I Westall. 14/06/38 Declar ation of Members Interests –None 14/06/39 Community Police - None 14/06/40 County Councillor County Cllr Lomax reported that there had recently been 2 hits on the bridge at New Smithy and he was awaiting costings for the Sat Nav signs, which need to have pictures of crossed out Sat Navs on them. Environmental Health were dealing with the rats that had been causing problems since being disturbed by clearance work at the Forge Works site. 14/06/41 Open Forum Mr Jack Hardman addressed the council on behalf of the Buxworth Village Olympics organisers expressing surprise about additional measures requested regarding vehicle access for transporting marquees and bouncy castle to Buxworth recreation ground after 19 years of preparing for this annual event. He confirmed that although he felt it completely unnecessary, they were proposing to address the highlighted situation by temporarily spanning the marked strip where the track crosses the pipeline with large metal plates. 14/06/42 Buxworth Village Olympics Fun Day RESOLVED: To change the order of business of the meeting and deal with item 6(b) Buxworth Village Olympice Fun Day next. -

WESTERN LANE Buxworth, High Peak 52 Western Lane, Buxworth, High Peak, Derbyshire SK23 7NS £499,950

WESTERN LANE Buxworth, High Peak 52 Western Lane, Buxworth, High Peak, Derbyshire SK23 7NS £499,950 The Property Locality ***WATCH THE VIDEO TOUR*** Commanding magnificent Buxworth is a popular village located just off the A6 near to forward views over playing fields and countryside, a spacious Whaley Bridge and Chinley. Home to the Bugsworth Basin on and versatile four bedroom detached property. the Peak Forest Canal. There is a local primary school and Accommodation arranged over three floors and comprising: excellent community network. Nearby towns have direct rail entrance hall, 24ft living room, separate dining room, refitted links to Manchester and Sheffield. The towns of Chapel En Le 21ft breakfast kitchen, two ground floor bedrooms and a Frith and Whaley Bridge are approximately one mile away, shower room, lower ground floor 22ft reception room, first and have a wider array of schools, shops, supermarkets, pubs floor master bedroom with en-suite, second bedroom and and sporting activity clubs further bathroom. Well presented throughout and ideally located in the popular village of Buxworth. Ample off road parking, garage, private gardens with attractive dry stone walling. Viewing highly recommended. Energy rating TBC Postcode - SK23 7NS • Versatile Four Bedroom Detached • Fabulous Forward Views EPC Rating - • Popular Village Location Local Authority - High Peak • Extended Accommodation over Three Floors Council Tax - Band E • 24ft Living Room, 22ft Cinema Room, 21ft Breakfast Kitchen Plus Separate Dining Room • Ample Driveway Parking and Garage These particulars are believed to be accurate but they are not guaranteed and do not form a contract. Neither Jordan 14 Market Street, Disley, Cheshire, SK12 2AA Fishwick nor the vendor or lessor accept any responsibility in respect of these particulars, which are not intended to be statements or representations of fact and any intending purchaser or lessee must satisfy himself by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of the statements contained in these particulars.