THE APOSTLE of METHODISM in the SOUTH SEAS by F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Fleet Marine James Lee ©Cathy Dunn and Glen Lambert September 2017

First Fleet Marine James Lee ©Cathy Dunn and Glen Lambert September 2017 James Lee was a marine private in the 35th Portsmouth Company, enlisted in the NSW Marines, and arrived in NSW aboard Scarborough in Jan 1788. James was a private, assigned to Captain Campbell's Company of the Port Jackson garrison. In Nov 1788 his name appears on the muster roll of the Marine Garrison for NSW Settlement.1 Some family historians believe that James Lee arrived on Norfolk Island aboard the Golden Grove in October 1788; however, records show that this is simply not the case.2 James Lee is also said to have been sent to Norfolk Island also on 9 April 1792, to superintend the growing of flax aboard the Pitt, which arrived on Norfolk Island from Port Jackson on 23 April 1792, sailing for Bengal on 7 May 1792. The Pitt actually left Sydney on 7 April 1792, she took no marines to Norfolk Island in April 1792, on board were 52 male and 5 female convicts and 9 males and one female stowaway convict. One asks the question was James Lee ever on Norfolk Island where he cohabited with Sarah Smith (1st) fathering children – William and Maria Smith – Lee. This has resulted in the “Lee Family Saga”. There was no land granted to a James Lee on Norfolk Island.3 James Lee is not listed in any of the Kings List 1800/1802, but most marines do not feature in these lists.4 More notably, James Lee is not listed in the Norfolk Island Victualling book 1792-1796, which is quite a comprehensive record of inhabitants on Norfolk Island. -

History and Causes of the Extirpation of the Providence Petrel (Pterodroma Solandri) on Norfolk Island

246 Notornis, 2002, Vol. 49: 246-258 0029-4470 O The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2002 History and causes of the extirpation of the Providence petrel (Pterodroma solandri) on Norfolk Island DAVID G. MEDWAY 25A Norman Street, New Plymouth, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract The population of Providence petrels (Pterodroma solandri) that nested on Norfolk Island at the time of 1st European settlement of that island in 1788 was probably > 1 million pairs. Available evidence indicates that Europeans harvested many more Providence petrels in the years immediately after settlement than previously believed. About 1,000,000 Providence petrels, adults and young, were harvested in the 4 breeding seasons from 1790 to 1793 alone. Despite these enormous losses, many Providence petrels were apparently still nesting on Norfolk Island in 1795 when they are last mentioned in documents from the island. However, any breeding population that may have survived there until 1814 when Norfolk Island was abandoned temporarily was probably exterminated by the combined activities of introduced cats and pigs which had become very numerous by the time the island was re-occupied in 1825. Medway, D.G. 2002. History and causes of the exhrpation of the Providence petrel (Pterodroma solandri) on Norfolk Island. Notornis 49(4): 246-258. Keywords Norfolk Island; Providence petrel; Pterodroma solandri; human harvesting; mammalian predation; extupation INTRODUCTION in to a hole which was concealed by the birds Norfolk Island (29" 02'S, 167" 57'E; 3455 ha), an making their burrows slant-wise". From the Australian external territory, is a sub-tropical summit, King had a view of the whole island and island in the south-west Pacific. -

A New Chapter Launched Into a Covid-19 World

1788 AD Magazine of the Fellowship of First Fleeters ACN 003 223 425 PATRON: Her Excellency The Honourable Marjorie Beazley AC QC To live on in the hearts and minds Volume 52 Issue 2 53rd Year of Publication April-May 2021 of descendants is never to die A NEW CHAPTER LAUNCHED INTO A COVID-19 WORLD Congratulations to the twenty Victorian members who ton, Secretary Geoff Rundell, Treasurer Susan Thwaites braved the ever-present threat of lockdown, donned and Committee member Sue-Ellen McGrath. They are their masks and gathered, socially distanced of course, pictured below. Two other committee members, not on Saturday 6 February at the Ivanhoe East Anglican Hall, available at the meeting, had previously said they would definitely intent on forming a chapter of their own. like to serve on the committee and so were approved. The groundwork was done by our Fellowship Director, They are Cheryl Turner and Simon Francis. Paul Gooding, as Chapter Establishment Officer, who attended the launch along with Jon and Karys Fearon, President and Chapter Liaison Officer. Paul gave special thanks to sisters Pam Cristiano and Adrienne Ellis who arranged the venue and served a delicious morning tea. This was appreciated by all, especially those who had come from afar such as Bendigo and further afield. Pam’s husband, the Church treasurer and Covid-Safe officer, had prepared the hall and supervised the required clean- Susan Geoff Sue-Ellen Chris ing afterwards. Without it even being called for, a member suggested The meeting took the format usual on such occasions, that the new chapter be called Port Phillip Chapter and with President Jon in the chair, giving the welcome and this was heartily agreed upon with minimal discussion outlining, with plenty of good audience interaction, a and without dissent. -

![An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2437/an-account-of-the-english-colony-in-new-south-wales-volume-1-822437.webp)

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Collins, David (1756-1810) A digital text sponsored by University of Sydney Library Sydney 2003 colacc1 http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/colacc1 © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Prepared from the print edition published by T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies 1798 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1798 F263 Australian Etext Collections at Early Settlement prose nonfiction pre-1810 An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Contents. Introduction. SECT. PAGE I. TRANSPORTS hired to carry Convicts to Botany Bay. — The Sirius and the Supply i commissioned. — Preparations for sailing. — Tonnage of the Transports. — Numbers embarked. — Fleet sails. — Regulations on board the Transports. — Persons left behind. — Two Convicts punished on board the Sirius. — The Hyæna leaves the Fleet. — Arrival of the Fleet at Teneriffe. — Proceedings at that Island. — Some Particulars respecting the Town of Santa Cruz. — An Excursion made to Laguna. — A Convict escapes from one of the Transports, but is retaken. — Proceedings. — The Fleet leaves Teneriffe, and puts to Sea. -

Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon

Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon Worgan, George B. A digital text sponsored by Australian Literature Gateway University of Sydney Library Sydney 2003 http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/worjour © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by Library Council of New South Wales; Library of Australian History Sydney 1978 71pp. All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: [1788] 994.4/179 Australian Etext Collections at early settlement diaries pre-1810 Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon Sydney Library Council of New South Wales; Library of Australian History 1978 Journal of A First Fleet Surgeon Letter (June 12-June 18 1788) Sirius, Sydney Cove, Port Jackson — June 12th 1788. Dear Richard. I think I hear You saying, “Where the D—ce is Sydney Cove Port Jackson”? and see You whirling the Letter about to find out the the Name of the Scribe: Perhaps You have taken up Salmons Gazetteer, if so, pray spare your Labour, and attend to Me for half an Hour — We sailed from the Cape of Good Hope on the 12th of November 1787– As that was the last civilized Country We should touch at, in our Passage to Botany Bay We provided ourselves with every Article, necessary for the forming a civilized Colony, Live Stock, consisting of Bulls, Cows, Horses Mares, Colts, Sheep, Hogs, Goats Fowls and other living Creatures by Pairs. We likewise, procured a vast Number of Plants, Seeds & other Garden articles, such, as Orange, Lime, Lemon, Quince Apple, Pear Trees, in a Word, every Vegetable Production that the Cape afforded. -

Report to the Australian Bicentennial Authority on the December 1983 Preliminary Expedition to the Wreck of H.M.S

I ~ REPORT TO THE AUSTRALIAN BICENTENNIAL AUTHORITY ON THE DECEMBER 1983 PRELIMINARY EXPEDITION TO THE WRECK OF H.M.S. SIRIUS (1790) AT NORFOLK ISLAND Graeme Henderson Curator Department of Maritime Archaeology Western Australian Museum January 1984 Report - Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Museum, No. 22 • I I "You never saw such dismay as the news of the wreck occasioned among uS all; for, to use a sea term, we \ looked upon her as out sheet anchor". Extract of a letter from an officer. 14 April 1790. HRNSW 2:1 p.760 • CONTENTS • Page INTRODUCTION vi ACKNOWLEDGE~IENTS vii 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1. 2. WORK CARRIED OUT ON THE I SIRlUS I WRECK SINCE 1900 17. 3. THE DECEMBER 1983 AUSTRALIAN BICENTENNIAL PROJECT 19. EXPEDITION A. Aims B. Logistics C. Personnel D. Summary of Activities E. D3script::.on of Site F. Methodology on Site 4. SITE IDENTIFICATION 32. A. Location of the Wreck B. Date Range of Artefacts C. Nature and Quantity of Artefacts D. Other Shipwrecks in the Area 5. KNOII'N HMS I SIRlUS I ARTEFACTS 36. A. Artefacts in New South Wales B. Artefacts on Norfolk Island C. Signifi cance of the HNS 'Sir ius ' Artefacts 6. RECOMl-IENDATIONS 68. A. Site Security B. Site Managem ent c. in:) Ar tefact.; Already Ra i sed f r om the I Si ri u5 ' D. Survey and Excavation E. Conservation of the Collection F. Housing and Display 7. REFERENCES 73. • ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1- Dimensional sketch of H.M.S. Sirius. A reconstruction by Captain F.J. Bayldon R.N.R. -

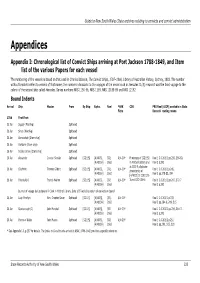

Chronological List of Convict Ships

Guide to New South Wales State archives relating to convicts and convict administration Appendices Appendix I: Chronological list of Convict Ships arriving at Port Jackson 1788-1849, and Item list of the various Papers for each vessel The numbering of the vessels is based on that used in Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1983. The number without brackets refers to vessels of that name; the number in brackets to the voyages of the vessel such as Hercules II (3) means it was the third voyage to the colony of the second ship called Hercules . Series numbers NRS 1150-56, NRS 1159, NRS 12188-89 and NRS 12192. Bound Indents Arrival Ship Master From By Ship Alpha. Reel *ARK COD PRO Reel [AJCP] available in State Fiche Records' reading rooms 1788 First Fleet 25 Jan Supply (Warship) Spithead 26 Jan Sirius (Warship) Spithead 26 Jan Borrowdale (Store ship) Spithead 26 Jan Fishburn (Store ship) Spithead 26 Jan Golden Grove (Store ship) Spithead 26 Jan Alexander Duncan Sinclair Spithead [SZ115] [4/4003], 392, 614-20* Photocopy of [SZ115] Reel 1 C.0.201/2 pp.235, 256-63, [4/4003A] 2662 in Mitchell Library and Reel 2 p.292 at COD 9; duplicate 26 Jan Charlotte Thomas Gilbert Spithead [SZ115] [4/4003], 392, 614-20* Reel 1 C.0.201/2 p.245, photocopies of [4/4003A] 2662 Reel 2 pp.278-83, 294 [4/4003] at COD 131- 26 Jan Friendship I Francis Walton Spithead [SZ115] [4/4003], 392 614-20* 3 and COD 134-6 Reel 1 C.0.201/2 pp.247, 272-7 [4/4003A] 2662 Reel 2 p.292 Journal of voyage by Lieutenant R Clark in Mitchell Library, Safe 1/27 including return of convicts on board 26 Jan Lady Penrhyn Wm. -

The Rev Richard Johnson As Australia's First Chaplain Spent 12 Years in Australia from 1788 to 1800

Your Excellency, Honourable Professor Marie Bashir, Church leaders, ladies & gentlemen; The Rev Richard Johnson as Australia's first Chaplain spent 12 years in Australia from 1788 to 1800. The first six years as Chaplain were by himself though the Rev James Bain a Military Chaplain to the NSW Corp arrived three & a half years later in September 1791. Johnson had to fulfill several roles as military chaplain, prison chaplain, parish priest & as a missionary particularly to the aboriginals as well as being a husband , father & provider especially during the early years of food deprivation. He & his wife lived on the ship Golden Grove for some months before a cabbage palm walled building was built with a thatched roof which leaked continually flooding the dwelling during heavy rainfalls. (See lot 30 above red arrow in James Mehans 1807 map of Sydney) Several years later a permanent building was erected a block away from here where the Lands building now stands with the many statues of pioneering explorers on its walls and opposite is a drinking fountain in Macquarie Place at the corner of Bridge & Loftus Streets with the words from John 4:13 & 14 “whoever drinketh of this water shall thirst again; But whoever drinketh of the water that I shall give shall never thirst". William Wilberforce & John Newton, the former slave trader of Amazing Grace fame were the chief sponsors of the Botany Bay chaplaincy, Newton becoming Johnson's important mentor, confidant & advisor, calling him the "first Apostle to the South Seas". He was encouraged not to yield to the secular battle at the time raging against the Age of Faith being challenged by the Age of Reason & Relativism – a battle that continues to this present day! After Arthur Philip left in December 1792, Major Francis Grose took over administration of the colony & was uncooperative viewing Anglican Evangelicals & Methodists as trouble makers though he gave significant support to Rev. -

DAVID BLACKBURN Papers, 1785-96 Reel M971

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT DAVID BLACKBURN Papers, 1785-96 Reel M971 Mr T. Grix Burgh next Aylsham Norfolk National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1976 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE David Blackburn (1753-1795) was born in Newbury, Berkshire, the son of the Reverend John Blackburn. After his father’s death in 1762, the family moved to Norwich. In 1779 je joined the Royal Navy with the rank of midshipman. By 1785 he was the master on HMS Flora, serving in the West Indies. In April 1787 Blackburn was appointed master on the tender Supply, commanded by Lieutenant Henry Ball, bound for Botany Bay as part of the First Fleet. The ship arrived in Botany Bay on 18 January 1788 and a few days later Blackburn was in the party that explored Port Jackson. In February 1788 the Supply sailed to Norfolk Island to establish a penal settlement. Blackburn visited Norfolk Island again in September 1788 commanding the transport Golden Grove. In 1790 the Supply sailed to Batavia for provisions and, following its return to Sydney, Blackburn commanded it on two visits to Norfolk Island. In May 1792 the Supply returned to England and Blackburn was discharged. He joined HMS Dictator in 1793. He died at Haslar Naval Hospital. THE LETTERS OF DAVID BLACKBURN The original letters written by David Blackburn to his sister, and the other papers filmed by the AJCP, were acquired by the State Library of New South Wales in 1999. The letters were reproduced in Derick Neville. Blackburn’s Isle (Lavenham UK, 1975). 2 DAVID BLACKBURN Reel M971 Margaret Blackburn (Norwich) to Blackburn, 3 April 1785: mismanagement of their brother; plans of mother and herself to offer board and education to a few young women; seamen and balloons. -

Richard Johnson Psalm 116, John 15:18-23 Three Men and a Baby Colony

Richard Johnson Psalm 116, John 15:18-23 Three Men and a Baby Colony If you were to go into the city, there’s a place where I would like you to stand. I stood there last week. It’s down at the Circular Quay end of Castlereagh street – on the corner of Bligh and Hunter Streets. In a little square, there’s a monument – passed by and unread by hundreds of people every day. Imagine you are standing in that spot, but instead of looking up at the tall buildings, and hearing the noise of the cars and the buses, above you is a great tree. You are in a wilderness – and the sounds you hear are the sounds of kookaburras – and the sounds of marching feet. For it very near that spot – at the corner of Bligh and Hunter Streets – that on Sunday 3rd February 1788, the first Christian church service was held in the Colony of New South Wales. Just imagine it… Out in the harbour are moored eleven ships – the ships of the First Fleet, having carried just over a thousand people from Southampton. There’s the Governor, Captain Arthur Phillip, twenty officials and their servants, 213 marines with some wives and children, more than 750 convicts – one chaplain and his wife – as well as one eternal optimist – a certain James Smith, the man who had actually stowed away on the First Fleet! The Fleet has taken 36 weeks to reach Botany Bay – and they arrive just four days before the two French frigates commanded by la Perouse also turn up – and after a few more days they transfer the site of the new colony to Farm Cove in Port Jackson on January 26. -

The First Fleet

THE FIRST FLEET In 1779, nine years after Sir Joseph Banks landed in Botany Bay with Captain Cook, he told the British Government that New South Wales was a good place to send convicts. In 1786 the British government decided to send convicts to Botany Bay because their jails were full. They gathered together large numbers of convicts, responsible for both petty and serious crimes such as stealing, burglary, highway robbery and possession of firearms . D epending on their crimes, the convicts were sentenc ed to either 7 or 14 years of transportation, or to a life of transportation in Australia. The first convicts came to Australia in ships known as the First Fleet. There were eleven ships in the First Fleet and they were all commanded by Captain Arthur Phi llip. The HMS Sirius and HMS Supply were naval escorts. These ships carried guns, marines (who were responsible for guarding the convicts), the marine’s families, surgeons and other officials and skilled men. They led the other nine ships. The Alexande r, Charlotte, Friendship, Lady Penrhyn, Prince of Wales and Scarborough all carried convicts. Golden Grove, Fishburn and Borrowdal carried food, transport and other provisions. It took the eleven ships nearly nine months to reach Australia. They all arr ived within days of one another. The ships of the First Fleet made three stops along the way. The Route May 1787 – the ships set sail from Portsmouth in England. June 1787 – the ships stopped in Tenerife (one of the Canary Islands off the north - western co ast of Africa) to stock up on fresh water, vegetables and meat. -

2. the British Invasion of Australia. Convicts: Exile and Dislocation

Lives in Migration: Rupture and Continuity 2. The British Invasion of Australia. Convicts: Exile and Dislocation Sue Ballyn Copyright©2011 Sue Ballyn. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and publication are properly cited and no fee is charged. On January the 26th 1788 eleven British ships under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, first Governor of the new colony, anchored on the east coast of Australia at Sydney Cove and raised the British Flag.i Known as the First Fleet the ships sailed from England on the 13th of May 1787. All told, the First Fleet carried 1,500 people comprised of convicts, crew and guards. As Bateson points out: The returns of the prisoners are contradictory, but the best evidence indicates that the six convict ships sailed with 568 male and 191 female prisoners – a total of 759 convicts (…) (Bateson 1985: 97). The route followed by the First Fleet can be seen on the map below:ii Following the direction of the prevailing trade winds and ocean currents, the route took the First Fleet from England to the Canary Islands, then southwards across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro to take on supplies,iii then south-eastward following the westerly winds across the Atlantic to the Cape and finally from there across the Indian and Southern Oceans to their final destination.iv Robert Hughes gives a good idea of how many of those on board must have felt as they departed from the Cape: “Before them stretched the awesome, lonely void of the Indian and Southern Oceans, and beyond that lay nothing they could imagine” (1987: 82).