How We Talk About the Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protocol for Direct Assistance for the Capital Gazette Families Fund

Protocol for Direct Assistance for the Capital Gazette Families Fund BACKGROUND On June 28, 2018 a gunman forced his way into the Capital Gazette newsroom in Annapolis with a shotgun killing five people and injuring two others. Officers responded to the scene within a minute of the rampage and found employees fleeing from the building. The suspect was found hiding under a desk and was arrested. The Annapolis community was shocked and heartbroken. Grieving colleagues began covering the story — some of them immediately upon escaping the building. The following morning, the Community Foundation of Anne Arundel County (CFAAC) was contacted by the Baltimore Sun Media Group and asked to administer the funds that were being donated to support the victims and their families. The Capital Gazette Families Fund (Fund) was established in coordination with tronc, Inc., to honor the lives of the five employees that were killed during the tragic shooting. While we know financial gifts cannot erase the traumatic impacts of tragedy, we hope that these gifts, given by thousands of people from around the world, will be a symbol of caring and help the employees and their families begin to heal. Through this fund we cannot solve all of the problems arising from this event, we cannot bring back those who were killed, nor erase that which was witnessed and endured by the survivors. The gifts made from this Fund are qualitatively different from other sources of tragedy relief. These gifts are not based on any economic loss or expenses incurred as a result of the incident. Additional assistance may be provided by the Maryland Criminal Injuries Compensation Board and other sources. -

A Call to the Media to Change Reporting Practices for the Coverage of Mass Shootings

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 60 Gun Violence as a Human Rights Violation 2019 A Call to the Media to Change Reporting Practices for the Coverage of Mass Shootings Jaclyn Schildkraut Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Oswego Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Jaclyn Schildkraut, A Call to the Media to Change Reporting Practices for the Coverage of Mass Shootings, 60 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 273 (2019), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol60/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Call to the Media to Change Reporting Practices for the Coverage of Mass Shootings Jaclyn Schildkraut * INTRODUCTION Mass shootings continue to be a cause for concern in the United States, fueled in part by the extensive media coverage these events garner. When word of another shooting breaks, the news media often interrupt regularly scheduled programming with reporting or live updates from the scene; newspaper stories are churned out at a rapid pace, expedited by the availability of digital media. Depending on the severity of the attack, the coverage may last hours, days, or, in the most extreme examples like the recent shootings in Las Vegas, NV (2017), Sutherland Spring, TX (2017), Parkland, FL (2018), and Pittsburgh, PA (2018), weeks. -

Analyzing Polarization in Social Media: Method and Application to Tweets on 21 Mass Shootings

Analyzing Polarization in Social Media: Method and Application to Tweets on 21 Mass Shootings Dorottya Demszky1 Nikhil Garg1 Rob Voigt1 James Zou1 Matthew Gentzkow1 Jesse Shapiro2 Dan Jurafsky1 1Stanford University 2Brown University fddemszky, nkgarg, robvoigt, jamesz, gentzkow, [email protected] jesse shapiro [email protected] Abstract 2016) and Facebook (Bakshy et al., 2015). Prior NLP work has shown, e.g., that polarized mes- We provide an NLP framework to uncover sages are more likely to be shared (Zafar et al., four linguistic dimensions of political polar- 2016) and that certain topics are more polarizing ization in social media: topic choice, framing, affect and illocutionary force. We quantify (Balasubramanyan et al., 2012); however, we lack these aspects with existing lexical methods, a more broad understanding of the many ways that and propose clustering of tweet embeddings polarization can be instantiated linguistically. as a means to identify salient topics for analy- This work builds a more comprehensive frame- sis across events; human evaluations show that work for studying linguistic aspects of polariza- our approach generates more cohesive topics tion in social media, by looking at topic choice, than traditional LDA-based models. We ap- framing, affect, and illocutionary force. ply our methods to study 4.4M tweets on 21 mass shootings. We provide evidence that the 1.1 Mass Shootings discussion of these events is highly polarized politically and that this polarization is primar- We explore these aspects of polarization by study- ily driven by partisan differences in framing ing a sample of more than 4.4M tweets about rather than topic choice. -

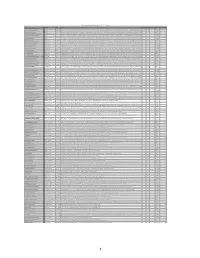

Mother Jones Mass Shootings Database

Mother Jones - Mass Shootings Database, 1982 - 2019 - Sheet1 case location date summary fatalities injured total_victims location age_of_shooter Dayton entertainment district shooting Dayton, OH 8/4/19 Connor Betts, 24, died during the attack, following a swift police response. He wore tactical gear including body armor and hearing protection, and had an ammunition device capable of holding 100 rounds. Betts had a history of threatening9 behavior27 dating 36backOther to high school, including reportedly24 having hit lists targeting classmates for rape and murder. El Paso Walmart mass shooting El Paso, TX 8/3/19 Patrick Crusius, 21, who was apprehended by police, posted a so-called manifesto online shortly before the attack espousing ideas of violent white nationalism and hatred of immigrants. "This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion22 of Texas,"26 he allegedly48 Workplacewrote in the document. 21 Gilroy garlic festival shooting Gilroy, CA 7/28/19 Santino William LeGan, 19, fired indiscriminately into the crowd near a concert stage at the festival. He used an AK-47-style rifle, purchased legally in Nevada three weeks earlier. After apparently pausing to reload, he fired additional multiple3 rounds12 before police15 Other shot him and then he killed19 himself. A witness described overhearing someone shout at LeGan, "Why are you doing this?" LeGan, who wore camouflage and tactical gear, replied: “Because I'm really angry." The murdered victims included a 13-year-old girl, a man in his 20s, and six-year-old Stephen Romero. Virginia Beach municipal building shooting Virginia Beach, VA 5/31/19 DeWayne Craddock, 40, a municipal city worker wielding handguns, a suppressor and high-capacity magazines, killed en masse inside a Virginia Beach muncipal building late in the day on a Friday, before dying in a prolonged gun battle12 with police.4 Craddock16 reportedlyWorkplace had submitted his40 resignation from his job that morning. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 26, 2018 No. 126 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- strengthen education, and combat called to order by the Speaker pro tem- nal stands approved. human trafficking. I have always relied pore (Mr. CURTIS). f upon her counsel and appreciate her f forthrightness and her integrity. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE As she leaves my office and begins DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the the next phase of her career working PRO TEMPORE gentleman from Maryland (Mr. BROWN) for a member of the California State The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- come forward and lead the House in the Senate, I know she will continue to fore the House the following commu- Pledge of Allegiance. serve the people of California well. nication from the Speaker: Mr. BROWN of Maryland led the f WASHINGTON, DC, Pledge of Allegiance as follows: July 26, 2018. I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the REUNITE EVERY CHILD I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN R. United States of America, and to the Repub- IMMEDIATELY CURTIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on this lic for which it stands, one nation under God, day. indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. (Mr. BROWN of Maryland asked and PAUL D. RYAN, f was given permission to address the Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

INF529: Security and Privacy in Informatics

INF529: Security and Privacy In Informatics Social Networks Prof. Clifford Neuman Lecture 6 21 February 2020 OHE 100C Course Outline • What data is out there and how is it used • Technical means of protection • Identification, Authentication, Audit • The right of or expectation of privacy • Social Networks and the social contract – February 21st • Criminal law, National Security, and Privacy – March 6th • Big data – Privacy Considerations – March 13th • Civil law and privacy Regulations – March 27th • International law and conflict across jurisdictions – April 3rd • The Internet of Things – April 10th • Technology – April 17th • Other Topics – April 24th • The future – What can we do – may 1st March 6th Presentations Criminal Law, National Security, and Privacy Presentations on March 6th • Various elements related to national security and policing use of information. • Glenn Johnson • Madhuri Jujare • Joshua Vagts • Shagun Bhatia • Anthony Cassar • Haotian Mai • Harshit Kothari • Tejas Pandey • Uddipt Sharma March 13th Presentations Privacy Considerations in Big Data and AI • Kaijing Zhang • Brendan Chan • Aashray Aggarwal • Dwayne Robinson • Di Rama • Zhejie Cui • Zishu Wang New Readings • [CAS] Cloak and Swagger: Understanding Data Sensitivity Through the Lens of User Anonymity. • [Levemore] Saul Levemore, "The Offensive Internet: Speech, Privacy, and Reputation" • [Nissenbaum] Helen Nissenbaum, "Privacy in Context: Technology, Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life" Social Networks and Social Media Services that Enable us to: – Share our thoughts and experiences – Record intricate details of our lives – Create communities of like minded individuals – Manage our relationships with others online. The intersections of technology with social interaction. Bulletin Boards, AOL, Myspace, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, SnapChat, and many related services. But also includes email and the rest of the web. -

Firearm Licensing Laws Or Requiring a Permit-To-Purchase a Handgun Is Associated with Lower Levels of Gun Deaths

Summary: There is strong evidence that mandatory firearm licensing laws or requiring a permit-to-purchase a handgun is associated with lower levels of gun deaths. This study found that of the 27 deadliest shootings over the last six years where we could identify how the firearms were obtained, a federal licensing requirement may have prevented the shooter from acquiring the firearms used in 52% of the incidents. In these 14 incidents, 169 individuals were fatally shot and 131 individuals were shot and injured. Objective: To estimate how many of the nation’s deadliest mass shootings could have been prevented and how many American lives could have been saved if the United States raised the federal standard for gun ownership and implemented a policy of federal firearm licensing. This study examines every shooting over the last six years (2013 – 2018) where five or more people were killed, excluding the perpetrator, in order to determine if a federal firearm licensing law may have prevented the perpetrator from acquiring the firearms used in the shooting. Background: An overwhelming majority of Americans support tightening the nation’s loose gun control laws and back 1 2 policies like gun licensing, expanding background checks to most firearm purchases, safe storage 3 4 requirements, and prohibitions against selling military-style assault weapons and 5 high-capacity magazines to civilians. Over the last several years, members of Congress have sought to advance legislation that would expand background checks to cover more gun sales. In 2013, a bipartisan bill by Senators Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Pat Toomey (R-PA) attempted to expand background checks to include sales by unlicensed dealers at gun shows and sales advertised online or in-print. -

SPJ Sept2018 Board Docs Website

THE SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 9A.M. TO NOON ROOM: PACA BALTIMORE HILTON BALTIMORE, MD “The people must know before they can act, and there is no educator to compare with the press.” – Ida B. Wells 1 2 AGENDA SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING TIME: 9 A.M.-NOON DATE: THURSDAY, SEPT. 27, 2018 ROOM: HILTON BALTIMORE STREAMED LIVE AT WWW.SPJ.ORG 1. Call to Order (Baker) 2. Roll Call (Newberry) a. Walsh g. South m. Schotz s. Gallagher b. Baker h. McClelland n. Koretzky t. Otte c. Tarquinio i. Chagani o. McKee u. Meyers d. Gallagher Newberry j. Harding p. Day v. Hall e. Kopen-Katcef k. Steffen q. Radske w. Kissel f. Bartlett l. Primerano r. Williams 3. Old/New Business – Executive session (Baker / Tarquinio) 1. EIJ Sponsorship & Task Force (Alex/Patti) 2. Review of executive director's 6-month evaluation 3. Region 10 4. Report of the SPJ President (Baker) 5. Report of the SDX Foundation President 6. Approval of Board Meeting Minutes (Baker) a. April 14-15, 2018 b. July 21, 2018 7. Staff report 1. Introduction of new staff (Bethel McKenzie) 2. Update on FY19 budget (Bethel McKenzie/Wong) 3. Update on projects (Google, Facebook, Scripps Leadership Institute) (Messing) 4. Report from Journalist on Call (Hicks) 3 8. Action/Discussion Items 1. Association Management (Bethel McKenzie) 2. Chapter Financial Rules (Bartlett) 3. Cuillier First Amendment Forever Fund (Bethel McKenzie / Messing) 4. Amendment to new rules to regional funds (Bartlett) 9. Public comment period a. -

Facial Recognition

Facial Recognition Portland Police Bureau Assistant Chief Ryan Lee Challenges • Law enforcement agencies who have failed to follow Department of Justice recommendations for Facial Recognition programs have consistently jeopardized public trust. 1 • Media has not shared complete information from recent National Institute of Science Technology (NIST) reports, and overemphasized studies where old algorithms2 and outdated science were used. 1. Face Recognition Police Development Template. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance. Retrieved from https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/Publications/Face- Recognition-Policy-Development-Template-508-compliant.pdf 2 Face Recognition Vendor Test Part 3: Demographic Effects. Retrieved from https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2019/NIST.IR.8280.pdf Analysis • NIST research (2019) revealed the accuracy of facial recognition algorithms have improved more than 20x since 2014. NIST found that 0.2% of searches, in a database of 26.6 million photos, failed to match the correct image, compared with a 4% failure rate in 2014, 1which is a 20x improvement over four years. • NIST highlighted Georgetown and MIT studies used 2014 algorithms, which produced high errors and were not reproduced with modern technology. 1 1. NIST Evaluation Shows Advance in Face Recognition Software’s Capabilities. Retrieved: https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2018/11/nist-evaluation-shows-advance-face- recognition-softwares-capabilities Potentials with Proper Oversight • Success or failure rests on policies and practices. • With more than 80 nodal points, a face is a unique blueprint distinguishing individual’s biometrics. As neural scientists suggest that no two faces are identical, with a clear photo FR can be more than 99% accurate.1 • Countless testimonials confirm FR systems have led to the arrests of dangerous perpetrators and missing endangered individuals. -

2019 Emmy® Award Nominations and Emmy® Recipients

2019 Emmy® Award Nominations and Emmy® Recipients 1A: Newscast - Morning (4:00am - 1pm) - Larger Markets (1-49) Good Morning Washington at 5am: Nationals Win! WJLA Jessica Glasser, Senior Producer Paige Gilmore, Editor Kristi Maryott, Director Kristen Powers, Reporter Ted Marschall, Producer * The Snowstorm of 2019 WRC Constance Howard, Executive Producer Alexandra Fruin, Producer Dylan Shue, Producer Jason Johnson, Director Timothy Saul, Technical Director Aaron Gilchrist, Anchor Melissa Mollet, Traffic Anchor Chuck Bell, Meteorologist Eun Yang, Anchor Molette Green, Reporter Adam Tuss, Reporter Nicholas Leimbach, Photographer Arun Raman, Content Producer Brandon Benavides, Content Producer Natasha Copeland, Assignment Editor Brittany Roembach, Content Producer 1B: Newscast - Morning (4:00am - 1pm) - Medium Market (50+) * 12 News Today WWBT Anthony Antoine, Anchor Andrew Freiden, Meteorologist Candice Smith, Traffic Anchor Michael Pegram, Producer Andrina Cason, Executive Producer Sarah Bloom, Anchor Olivia Ugino, Reporter David Perdue, Director Victoria Doss, Producer Sean Van Damme, Editor Alex Whittler, Reporter 62nd Emmy Awards – August 8, 2020 * indicates Emmy® Recipient www.capitalemmys.tv - 1 - 2019 Emmy® Award Nominations and Emmy® Recipients Dorian's path of destruction WTVR Alexandra Sosik, Producer Jaclyn Groves, Editor 2A: Newscast - Daytime (1pm - 8pm) - Larger Market (1-49) * 11 News at 6:00: Death of Rep. Elijah Cummings WBAL Charles Richardson, Producer Mike Gantt, Director Deadly Shootout WBFF Dominique Johnson, Producer -

Analyzing Polarization in Social Media: Method and Application to Tweets on 21 Mass Shootings

Analyzing Polarization in Social Media: Method and Application to Tweets on 21 Mass Shootings Dorottya Demszky1 Nikhil Garg1 Rob Voigt1 James Zou1 Matthew Gentzkow1 Jesse Shapiro2 Dan Jurafsky1 1Stanford University 2Brown University fddemszky, nkgarg, robvoigt, jamesz, gentzkow, [email protected] jesse shapiro [email protected] Abstract 2016) and Facebook (Bakshy et al., 2015). Prior NLP work has shown, e.g., that polarized mes- We provide an NLP framework to uncover sages are more likely to be shared (Zafar et al., four linguistic dimensions of political polar- 2016) and that certain topics are more polarizing ization in social media: topic choice, framing, affect and illocutionary force. We quantify (Balasubramanyan et al., 2012); however, we lack these aspects with existing lexical methods, a more broad understanding of the many ways that and propose clustering of tweet embeddings polarization can be instantiated linguistically. as a means to identify salient topics for analy- This work builds a more comprehensive frame- sis across events; human evaluations show that work for studying linguistic aspects of polariza- our approach generates more cohesive topics tion in social media, by looking at topic choice, than traditional LDA-based models. We ap- framing, affect, and illocutionary force. ply our methods to study 4.4M tweets on 21 mass shootings. We provide evidence that the 1.1 Mass Shootings discussion of these events is highly polarized politically and that this polarization is primar- We explore these aspects of polarization by study- ily driven by partisan differences in framing ing a sample of more than 4.4M tweets about rather than topic choice. -

Sending a Message News Publishers Create Their Own Identities Through Powerful Marketing Campaigns

Sending a Message News publishers create their own identities through powerful marketing campaigns Since 1884, THE authoritative voice of #NewsPublishing ING and E&P TEAM UP TO HONOR OPERATIONS ALL-STARS A PREVIEW OF #2020MEGACONF JANUARY 2020 | EDITORANDPUBLISHER.COM $8.95 JANUARY 2020 inside FOLLOW US ON BE OUR FRIEND ON VISIT US ONLINE EDITORANDPUBLISHER.COM 9 32 28 A Section Features Departments THINK LIKE AN EDITOR 2020 Mega-Conference Arrives CRITICAL THINKING The Canadian Journalism Foundation in Fort Worth Feb. 17-19 After the debacle at Deadspin, should launches ‘Doubt It?’ campaign to fight Annual tradeshow celebrates 10 years of it be a mandate that all sports journalists misinformation ...................p. 8 moving the industry forward .......p. 26 “stick to sports?” .................p. 15 NEVER ENOUGH NEWS Sending a Message DATA PAGE Community Impact Newspaper News publishers create their Job performance of local news, political expands into Atlanta region ........p. 9 own identities through powerful ads on Facebook, unsolved murders of marketing campaigns ...........p. 32 journalists in countries with worst record for justice, proportion of screen time MAKING AN IMPACT IN 2020 tweens and teens devote to various McClatchy launches subscription product 2020 Vision media activities ..................p. 18 for political obsessives ............p. 10 News publishers have a clear focus with finding innovation and success this year .......................p. 38 OPERATIONS FILING FOR THE FUTURE International Newspaper Group and E&P New RJI project seeks to preserve to honor operations ‘all-stars’ ....... p. 28 digital archives ...................p. 11 NEWSPEOPLE FULL SCREEN REDESIGN New hires, promotions and relocations USA TODAY upgrades website . ..... p. 14 across the industry .............