Approaches to Regulating Children's Television in Arab Countries S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia in View a CASBAA Market Research Report

Indonesia in View A CASBAA Market Research Report In Association with Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 6 1.1 Large prospective market providing key challenges are overcome 6 1.2 Fiercely competitive pay TV environment 6 1.3 Slowing growth of paying subscribers 6 1.4 Nascent market for internet TV 7 1.5 Indonesian advertising dominated by ftA TV 7 1.6 Piracy 7 1.7 Regulations 8 2. FTA in Indonesia 9 2.1 National stations 9 2.2 Regional “network” stations 10 2.3 Local stations 10 2.4 FTA digitalization 10 3. The advertising market 11 3.1 Overview 11 3.2 Television 12 3.3 Other media 12 4. Pay TV Consumer Habits 13 4.1 Daily consumption of TV 13 4.2 What are consumers watching 13 4.3 Pay TV consumer psychology 16 5. Pay TV Environment 18 5.1 Overview 18 5.2 Number of players 18 5.3 Business models 20 5.4 Challenges facing the industry 21 5.4.1 Unhealthy competition between players and high churn rate 21 5.4.2 Rupiah depreciation against US dollar 21 5.4.3 Regulatory changes 21 5.4.4 Piracy 22 5.5 Subscribers 22 5.6 Market share 23 5.7 DTH is still king 23 5.8 Pricing 24 5.9 Programming 24 5.9.1 Premium channel mix 25 5.9.2 SD / HD channel mix 25 5.9.3 In-house / 3rd party exclusive channels 28 5.9.4 Football broadcast rights 32 5.9.5 International football rights 33 5.9.6 Indonesian Soccer League (ISL) 5.10 Technology 35 5.10.1 DTH operators’ satellite bands and conditional access system 35 5.10.2 Terrestrial technologies 36 5.10.3 Residential DTT services 36 5.10.4 In-car terrestrial service 36 5.11 Provincial cable operators 37 5.12 Players’ activities 39 5.12.1 Leading players 39 5.12.2 Other players 42 5.12.3 New entrants 44 5.12.4 Players exiting the sector 44 6. -

Langue Catégorie Chaine Qualité • Cinéma DE • Allemagne Cinéma

Langue Catégorie Chaine Qualité •●★ Cinéma DE ★●• Allemagne Cinéma Family TV FHD HD Allemagne Cinéma Kinowelt HD Allemagne Cinéma MGM FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY ATLANTIC (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA 1 (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema 24 FHD HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema 24 HD HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA ACTION FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA ACTION (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA FAMILY (FHD) HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema HD FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA HITS (FHD) HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY EMOTION HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Hits HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Hits HD HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Krimi HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Nostalgie HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 1 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 2 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 3 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 4 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 5 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 6 •●★ Culture DE ★●• Allemagne Culture 3SAT HD Allemagne Culture A & E HD Allemagne Culture Animal Planet HD HD Allemagne Culture DISCOVERY HD HD Allemagne Culture Goldstar TV HD Allemagne Culture Nat Geo Wild HD Allemagne Culture Sky Dmax HD HD Allemagne Culture Spiegel Geschichte HD Allemagne Culture SWR Event 1 HD Allemagne Culture SWR Event 3 HD Allemagne Culture Tele 5 HD HD Allemagne Culture WDR Event 4 •●★ Divertissement DE ★●• Allemagne Divertissement13TH STREET FHD Allemagne Divertissement13TH STREET (FHD) HD Allemagne DivertissementA&E HD Allemagne DivertissementAustria 24 TV HD Allemagne DivertissementComedy Central / VIVA AT HD Allemagne DivertissementDMAX -

Who Owns the Broadcasting Television Network Business in Indonesia?

Network Intelligence Studies Volume VI, Issue 11 (1/2018) Rendra WIDYATAMA Károly Ihrig Doctoral School of Management and Business University of Debrecen, Hungary Communication Department University of Ahmad Dahlan, Indonesia Case WHO OWNS THE BROADCASTING Study TELEVISION NETWORK BUSINESS IN INDONESIA? Keywords Regulation, Parent TV Station, Private TV station, Business orientation, TV broadcasting network JEL Classification D22; L21; L51; L82 Abstract Broadcasting TV occupies a significant position in the community. Therefore, all the countries in the world give attention to TV broadcasting business. In Indonesia, the government requires TV stations to broadcast locally, except through networking. In this state, there are 763 private TV companies broadcasting free to air. Of these, some companies have many TV stations and build various broadcasting networks. In this article, the author reveals the substantial TV stations that control the market, based on literature studies. From the data analysis, there are 14 substantial free to network broadcast private TV broadcasters but owns by eight companies; these include the MNC Group, EMTEK, Viva Media Asia, CTCorp, Media Indonesia, Rajawali Corpora, and Indigo Multimedia. All TV stations are from Jakarta, which broadcasts in 22 to 32 Indonesian provinces. 11 Network Intelligence Studies Volume VI, Issue 11 (1/2018) METHODOLOGY INTRODUCTION The author uses the Broadcasting Act 32 of 2002 on In modern society, TV occupies a significant broadcasting and the Government Decree 50 of 2005 position. All shareholders have an interest in this on the implementation of free to air private TV as a medium. Governments have an interest in TV parameter of substantial TV network. According to because it has political effects (Sakr, 2012), while the regulation, the government requires local TV business people have an interest because they can stations to broadcast locally, except through the benefit from the TV business (Baumann and broadcasting network. -

Oasis Brightens up MBC MBC Takes Broadcastpro ME on an Exclusive Tour of Its Refurbished Studio and Sheds Light on the New Technology at Its Facility

PROLIGHTING The new studio at MBC. Oasis brightens up MBC MBC takes BroadcastPro ME on an exclusive tour of its refurbished studio and sheds light on the new technology at its facility of the kit was undertaken in-house, Dubai- facilities at MBC Group. based systems integrator Oasis Enterprises “I have worked in the news department Client: MBC was responsible for the lighting installation since 1998 and now instinctively know what Lighting SI: Oasis Enterprises at the studio. is suitable for our news operations. Our initial Key studio kit: Sony cams, Barco video walls. Lighting brands: ETC, DeSisti and Coemar The studio lighting is said to have been at plan was merely to design a temporary studio Location: Dubai least twelve years old and was in dire need but as the demand for it became stronger, of replacement. A brand new rigging system we felt the need to revamp the entire studio from DeSisti has replaced an older system so as to accommodate the needs of our news from the same manufacturer. channel. Everything, therefore, has been Early this year, MBC Group’s Al Arabiya news The installation includes a dimming and changed at the studio. channel went on air with a brand new look control solution from ETC and LED fittings “Of course, there are some expensive for some of its programmes thanks to a from Italian manufacturer Coemar. In addition, elements that could potentially be retained so completely refurbished studio and brand the studio sets are on wheels so they can be we have done that,” he explains. -

Mbc Group Picks Eutelsat's Atlantic Bird™ 7 Satellite

PR/69/11 MBC GROUP PICKS EUTELSAT’S ATLANTIC BIRD™ 7 SATELLITE TO SUPPORT HDTV ROLL-OUT ACROSS THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Paris, 31 October 2011 Eutelsat Communications (Euronext Paris: ETL) and MBC Group announce the signature of a multiyear contract for capacity on Eutelsat’s new ATLANTIC BIRD™ 7 satellite at 7 degrees West. The lease of a full transponder will enable MBC to expand its platform of channels addressing viewers in the Middle East and North Africa, particularly new HD content which the Group is preparing to launch in January 2012. The announcement was made at Digital TV Middle East, the broadcast and broadband conference taking place in Dubai from November 1 to 2. The new contract cements a 20-year relationship between Eutelsat and MBC Group which began in 1991 with the launch of MBC1, the first pan-Arab free-to-air satellite station. Over the past 18 years, MBC has developed a network comprising ten TV channels, two radio stations and a production house to forge a leading media and broadcasting group in the Middle East, among other media platforms such as VOD (shahid.net), SMS and MMS services. The move into HDTV reflects the Group's commitment to delivering the latest technology and superior television content. Launched on September 24, ATLANTIC BIRD™ 7 brings first-class resources to 7 degrees West, an established video neighbourhood delivering Arab and international channels into almost 30 million satellite homes. The satellite’s significant Ku-band resources enable broadcasters to launch new Standard Digital and HD content. -

Analisis Elemen Ekuitas Merek Rcti Dalam Persaingan Industri Televisi Swasta Di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Pada Empat Perguruan Tinggi Swasta Terkemuka Di Jakarta

ANALISIS ELEMEN EKUITAS MEREK RCTI DALAM PERSAINGAN INDUSTRI TELEVISI SWASTA DI INDONESIA: STUDI KASUS PADA EMPAT PERGURUAN TINGGI SWASTA TERKEMUKA DI JAKARTA Masruroh1; Awin Indranto2 ABSTRACT Article measured the element of RCTI brand equity consisting of brand awareness, brand association that formed brand image, perceived quality, and brand loyalty. The used research method was descriptive, this research desribe 400 student perception from four private universities in Jakarta on the RCTI brand equity in last 2005. The used sampling method was probability sampling using proportionate stratified random sampling technique. The brand awarness research result shows that RCTI brand is in the first level on top of mind level with 50,25% of the respondent. For the brand association, there are three associations that formed brand image of RCTI, which are RCTI Oke, Indonesian Idol, and Seputar Indonesia. Keywords: brand equity, competition, television industry ABSTRAK Artikel mengukur elemen ekuitas merek RCTI yang terdiri dari brand awareness (kesadaran merek), brand association (asosiasi merek) yang membentuk brand image (citra merek), perceived quality (persepsi kualitas), dan brand loyalty (loyalitas merek). Metode penelitian yang digunakan adalah deskriptif, yaitu menguraikan persepsi 400 mahasiswa di 4 universitas swasta terkemuka di Jakarta terhadap ekuitas merek RCTI pada akhir tahun 2005. Metode sampling yang digunakan adalah probability sampling dengan teknik proportionate stratified random sampling. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa merek RCTI berada pada urutan pertama di tingkat top of mind dengan 50,25% responden. Untuk brand association terdapat tiga asosiasi yang membentuk brand image RCTI, yaitu asosiasi RCTI Oke, Indonesian Idol, dan Seputar Indonesia. Kata kunci: ekuitas merk, persaingan, industri televisi 1, 2 Fakultas Ekonomi, Universitas Jayabaya, Jl. -

Twelve Arab Innovators Become Stars of Science Candidates on Mbc4

TWELVE ARAB INNOVATORS BECOME STARS OF SCIENCE CANDIDATES ON MBC4 Season 7’s Engineering Stage Kicks Off Doha, October 10, 2015 – Twelve of the Arab world’s most promising and remarkable young innovators beat thousands of rival applicants to be selected as candidates on the seventh season of Stars of Science, Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development ‘s (QF) “edutainment reality” TV program on MBC4. This selection concludes the casting phase and marks the onset of the highly competitive engineering stage of the program, in which candidates work tirelessly with mentors to turn their concepts into prototypes; further advancing QF’s mission of unlocking human potential in the next generation of aspiring young science and technology innovators. Chosen candidates have roots in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Egypt, Algeria, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Tunisa, reflecting the diversity that has characterized Stars of Science since its inception. Their distinct inventions feature smart technology that can solve problems in fields as varied as medical diagnostics, mobility for the physically challenged, sports, renewable energy and nutrition. On the first three episodes of Stars of Science, thousands of applicants from across the Middle East and North Africa were screened in a multi‐country casting tour by a panel of highly experienced jurors. In the latest Majlis episode, jury members selected twelve of the seventeen shortlisted applicants to become candidates, advancing them to the next phase of the competition, held at Qatar Science & Technology Park, a member of Qatar Foundation. As candidates enter the critical engineering stage, which spans three episodes, they compete against each other in three separate groups labeled; blue, red and purple. -

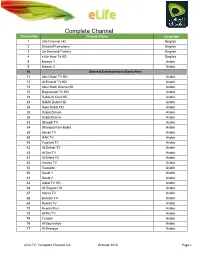

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

MBC Group (Middle East Broadcasting Center)

UAE 방송통신 사업자 보고서 MBC Group (Middle East Broadcasting Center) UAE 최초의 위성 민영 방송사 회사 프로필 상장여부 비상장사 桼1991년영국런던에서설립된 MBC Group 은아랍지역최초의 설립시기 1991 년 위성 민영 방송사로서10TV 개의 채널과 2 개의 라디오 채널 , Sheikh Waleed Al Ibrahim 주요 인사 회장 다큐제작사, 온라인플랫폼 등을 운영 중임 TV채널 10 개 TV 채널 , 2 개 라디오 채널 PO Box 76267, Dubai 주소 - MBC Group은 아랍 최초로 24 시간 무료 위성 방송을 Media City, Dubai, UAE 전화 +971 4 390 9971 제공하고 있음 매출 N/A 직원 수 약1,000 명 (‘10) - MBC Group은 회장 겸 CEO 인 Sheikh Waleed Al Ibrahim 과 홈페이지 www.mbc.net 사우디아라비아 왕실이 주요 주주이며, 자세한 지분 내역은 회사 연혁 공개되지 않음 2011HD 방송 시작 2008 타 중동 국가 진출 200324 시간 무료 영화 채널 런칭 桼MBC Group은 24 시간 뉴스 , 영화 , 드라마 , 여성 전용 , 유아 2002 두바이로 본사 이전 엔터테인먼트 등 다양한 채널을 운용하고 있으며, 시청자들에게 1994 사우디아라비아 진출 1991 설립 긍정적인 호응을 얻고 있음 -2011년 기준 주요채널시청률은 MBC 2 51.5%, MBC Action 47%, MBC 1 39.5% 로 타 방송사업자 대비 높은 시청률을 기록하고 있음 桼또한, 아랍 지역 대표 포털 사이트인MBC net 운영을 통해 스포츠 , 엔터테인먼트, 영화 , 음악 콘텐츠를 제공하고 있음 - 2011년 7 월 ,Shahid.net 서비스를 개시하여 , 온라인 TV 사업을 강화하고 있음에 따라MBC Group 의 UAE TV 시장에서의 입지가 더욱 견고해질 전망임 桼2011년 7 월 7 개채널에서 HD 방송을시작하였음 UAE TV시청율 (2011) 주요 채널 현황 순위 채널 %%% 장르 채널명 1 MBC 2 51.5 종합 엔터테인먼트 MBC 1 2 MBC Action 47 여성 엔터테인먼트 MBC 4 3 MBC 1 39.5 유아 엔터테인먼트 MBC 3 4 Dubai TV 32.7 5 Abu Dhabi Al Oula 32.6 영화 MBC 2, MBC Max, MBC Persia, MBC Action 6 MBC 4 32.1 뉴스 Al Arabiya 7 Al Jazeera 30.4 음악 Wanasah 8 Al Arabiya 29.1 9 Fox Movies 24.7 드라마 MBC Drama 10 Zee TV 24.6 라디오 MBC FM, Panorama FM - 1 - 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지 UAE 방송통신 사업자 보고서 □□□ 비전 및 전략 桼桼桼 비전 o정보 , 상호 작용 및 엔터테인먼트를 통해 아랍 세계의 삶을 풍요롭게 하는 글로벌 미디어 Group 桼桼桼 전략 o TV 와 온라인을 통한 혁신적인 정보 및 엔터테인먼트의 멀티 플랫폼 제공 o글로벌주요 TV 프로그램상용을통한 TV 시청점유율상승 □□□ 조직 현황 桼桼桼 -

Arabic Global 59

ARABIC GLOBAL 59. AL HAYAT CINEMA 120. BAHRAIN SPORT 1 180. AL RASHEED 60. AL NAHAR TV 121. BAHRAIN SPORT 2 181. AL GHADEER 1. AL JAZEERA ARABIC 61. AL HAYAT SPORT 122. BAHRAIN 55 182. AL QETHARA 2. AL JAZEERA ENGLISH 62. AL HAYAT MUSLSALAT 123. BAHRAIN TV 183. OMANN SPORT 3. AL JAZEERA MASR 63. AL HAYAT SERIES 124. ORIENT 184. ALMERGAB 2 4. AL JAZEERA MUBASHER 64. IMAGINE MOVIES 125. AGHAPY 185. TUNISIA TV 5. MBC 1 65. RUSSIA AL YAUM 126. DUBAI TV 186. TUNISIE TELEVISION 6. MBC WANASAH 66. DW TV ARABIC 127. MAEEN 187. MISRATA 7. MBC 4 67. EURO NEWS ARABIC 128. HAMASAT 188. OMAN TV 8. MBC ACTION 68. FUTURE INTERNATIONAL 129. MADANI 189. OMAN TV2 9. MBC MAX 69. FUTURE USA 130. MTV LEBANON 190. SAWSAN TV 10. MBC DRAMA 70. SYRIA SATELLITE 131. NOURSAT AL SHABAB 191. LIBYA AL HURRA 11. MBC MAGHREB 71. CNBC ARABIYAH 132. AL MASRAWIA 192. TOP MOVIES TV 12. MBC 3 72. MBC MASR 133. ABU DHABI DRAMA 2 193. AL HAQEQA 13. MBC PERSIA 73. PANORAMA DRAMA 2 134. AL ANWAR 194. ALL TV 14. MBC 2 74. CRT DRAMA 135. AL MANAR 195. AL LUBNANIA 15. ROTANA CINEMA 75. PANORAMA FILM 136. AL EKHBARIA 196. TAWAZON 16. ROTANA KHALIJIAH 76. PANORAMA DRAMA 137. CORAN TV 197. KIRKUK TV 17. ROTANA MUSIC 77. AL ARABIYAH AL HADATH 138. TELE LIBAN 198. AL FATH 18. ROTANA CLIP 78. AL ALARABIYA 139. AL YAWM PALESTINE 199. FM TV 19. ROTANA MASRIYA 79. FADAK TV 140. BEDAYA 200. -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

The Rest of Arab Television

The Rest of Arab Television By Gordon Robison Senior Fellow USC Annenberg School of Communication June, 2005 A Project of the USC Center on Public Diplomacy Middle East Media Project USC Center on Public Diplomacy 3502 Watt Way, Suite 103 Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org USC Center on Public Diplomacy – Middle East Media Project The Rest of Arab Television By Gordon R. Robison Senior Fellow, USC Center on Public Diplomacy Director, Middle East Media Project The common U.S. image of Arab television – endless anti-American rants disguised as news, along with parades of dictators – is far from the truth. In fact, Arab viewers, just like viewers in the U.S., turn to television looking for entertainment first and foremost. (And just as in the U.S., religious TV is a big business throughout the region, particularly in the most populous Arab country, Egypt). Arabs and Americans watch many of the same programs – sometimes the American originals with sub-titles, but just as often “Arabized” versions of popular reality series and quiz shows. Although advertising rates are low, proper ratings scarce and the long-term future of many stations is open to question, in many respects the Arab TV landscape is a much more familiar place, and far less dogmatic overall, than most Americans imagine. * * * For an American viewer, Al-Lailah ma’ Moa’taz has a familiar feel: The opening titles dissolve into a broad overhead shot of the audience. The host strides on stage, waves to the bandleader, and launches into a monologue heavy on jokes about politicians and celebrities.