A Memoir of the Magazine Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

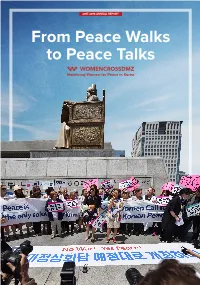

2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT from Peace Walks to Peace Talks

2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT From Peace Walks to Peace Talks Mobilizing Women for Peace in Korea LETTER FROM INTERNATIONAL COORDINATOR 2018 Steering Committee: Christine Ahn, International Coordinator Kozue Akibayashi, Women’s Int’l League for Peace & Freedom Aiyoung Choi, Nonprofit Management Consultant Dear Friends, Ewa Eriksson-Fortier, Retired Humanitarian Aid Worker Meri Joyce, Peace Boat, Global What a dramatic year it’s been. One year ago, Through talks, webinars, conferences, and the Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict Northeast Asia President Donald Trump threatened to unleash media, we reached millions with our calls for Regional Coordinator “fire and fury” on North Korea. Now, the prospect peace and diplomacy. We rallied our partners Gwyn Kirk, Women for Genuine Security Hye-Jung Park, Media Activist of permanent peace on the Korean Peninsula in South Korea and North Korea, women’s, Ann Wright, Retired US Army looms on the horizon, and Women Cross DMZ is peace, faith-based, humanitarian, and Korean Colonel, Diplomat Nan Kim, Associate Professor, University poised to play a key role in the process. diaspora organizations around the world to call of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for an end to the Korean War. We deepened our 2015 Delegation Members: How did we get here? partnerships with the South Korean women’s Gloria Steinem, Author and Activist peace movement, the Nobel Women’s Initiative, Janis Alton, Canadian Voice of Women for Peace The reversal began with the Winter Olympics, and Women’s International League for Peace Medea Benjamin, Code Pink when the two Koreas marched together carrying and Freedom and strengthened the U.S.-based Deann Borshay Liem, Filmmaker Hyun-Kyung Chung, Union the One Korea flag. -

Flouting the Establishment

Flouting The Establishment February 18, 2020 Category: Domestic Politics Download as PDF If those who are not ideologically-committed to the ultra-right-wing want a desirable outcome in the 2020 presidential election, it is important they understand why NON-ultra-right-wing endeavors (encompassing Progressives and corporatist Democrats alike) imploded four years earlier. It was not because the Democratic candidate was too far to the “Left”. And it certainly was not because she was too populist…let alone too Progressive. It was because Hillary Clinton–the only alternative to Donald Trump–was off- putting to many swing voters. There were two main reasons for this: She countenanced some of the daft pieties of political correct-ness, which many swing-voters found off-putting. As a corporatist Democrat, she was effectively the vicar of the very thing that on-the-fence voters were so set against: the “Establishment”. There were, of course, a confluence of factors that led to the disastrous outcome in 2016–among them: the glaring inauthenticity of Trump’s adversary (not to mention the DNC’s now-exposed machinations to prevent Bernie Sanders from receiving the Democratic nomination). {1} As I hope to show here, these two factors explain Clinton’s loss. Indeed, they represented things for which the rank and file had–and continues to have–contempt; and for very good reason. (The fact that Clinton ran what Barack Obama described as a “scripted, soul-less campaign” didn’t help either.) There are effectual and ineffectual ways to promote Progressive ideals; and the 2016 election illustrated–more than anything else–what NOT to do. -

Accessed 4/16/20

Joan Walsh, “The Troublesome Tara Reade Story,” The Nation, April 15, 2020. (https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/tara-reade-joe-biden-democrats/, accessed 4/16/20) Left- and right-wing Biden haters demanded that the media investigate her sexual assault charge. It did—and uncovered many reasons to doubt. There is no evidence that former vice president Joe Biden, now the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, sexually assaulted aide Tara Reade in 1993. There is no evidence that he did not. Reade claims he did—specifically, that he pushed her against a wall and digitally penetrated her against her will, when she worked in his US Senate office. Biden’s campaign firmly denies it. The story originated on the left, just about three weeks ago, when diehard Bernie Sanders supporter Katie Halper hosted Reade on her podcast, and encouraged her to tell her story publicly for the first time in 27 years. The story took off from there, on the left and the right, with certain Sanders supporters and Donald Trump backers (whose own man is credibly accused of sexual assault or extreme harassment by more than a dozen women) accusing the mainstream media of pro-Biden bias for not investigating the charges against him. But to those who hectored the media to investigate the allegations about Biden, believing it would validate Reade’s charges, the old adage applies: Be careful what you wish for. In the last two days, mainstream outlets, including The New York Times, Associated Press, have taken deep dives into Reade’s charges, and come up with a whole lot of confusion. -

N.J. Robinson Impossibilities No Longer Stood in the Way

My Affairs A MEMOIR OF THE MAGAZINE INDUSTRY (2016-2076) N.J. Robinson Impossibilities no longer stood in the way. One’s life had fattened on impossibilities. Before the boy was six years old, he had seen four impossibilities made actual—the ocean-steamer, the rail- way, the electric telegraph, and the Daguerreotype; nor could he ever learn which of the four had most hurried others to come… In 1850, science would have smiled at such a romance as this, but, in 1900, as far as history could learn, few men of science thought it a laughing matter. — The Education of Henry Adams I was emerging from these conferences amazed and exalted, con- vinced, one might say. It seemed to me that I traveled through Les Champs Elysées in a carriage pulled by two proud lions, turned into anti-lions, sweeter than lambs, only by the harmonic force; the dolphins and the whales, transformed into anti-dolphins and into anti-whales, made me sail gently on all the seas; the vul- tures, turned anti-vultures, carried me on their wings towards the heights of the heavens. Magnificent was the description of the beauties, the pleasures, and the delights of the spirit and the heart in the phalansterian city. — Ion Ghica My Affairs have been editing a magazine now for almost exactly sixty years. I hope to live a good while longer—life expectancy is shooting up so fast that now, at age eighty- Iseven, I may still not have reached my halfway point. Yet sixty is the sort of number that leads one to reflect. -

Università Degli Studi Di Padova Campagne Digitali: Le Nuove Forme

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Strategie di Comunicazione Classe LM-92 Tesi di Laurea Campagne digitali: le nuove forme di contatto e di engagement con l'elettore Relatore Laureando Prof. Michele Cocco Sara Bassi n° matr.1192348 / LMSGC a.a. 2019 / 2020 Indice Introduzione I. Comunicazione politica: struttura e contesto 1. Ruolo centrale dei media 2. La mediatizzazione 2.1 Effetti della mediatizzazione 2.2 Internet e la mediatizzazione 3. L’evoluzione delle campagne elettorali 3.1 Le campagne premoderne 3.2 Le campagne moderne 3.3 Le campagne postmoderne 4. Il rapporto tra politica e marketing 4.1 Un approccio diverso 4.2 Professionalizzazione della comunicazione politica 4.3 Fast Politics 4.4 Strumenti del marketing politico II. Dalla campagna post-moderna alla campagna digitale 1. Dall’Internet unidirezionale all’Internet partecipativo 2. Campagna online o campagna digitale? 3. Networked Politics 3.1 Online come organizzazione dell’offline 4. Utilizzo dei big data III. Nuove forme di contatto con l’elettorato 1. Definizione di contatto 1.1 Primo contatto – secondary audience, viralità 1.2 Contatto successivo – silly citizenship, slacktivism 2. Descrizione metodologia ricerca e corpus 2.1 Perché sono nuove forme di contatto 1 IV. Forme di Primo contatto 1. Twitch 2. Spotify playlist 3. Meme 4. Tiktok 5. Podcasting V. Forme di Contatto successivo 1. Gamification 2. Selfie Line 3. Petizioni online 4. Meme VI. Conclusioni 1. Online VS offline 2. Nuove forme di contatto e Covid-19 VII. Bibliografia VIII. Appendice 2 Introduzione Durante il secolo scorso, i media elettronici hanno raggiunto un ruolo centrale nei processi comunicativi e sociali, determinando una crescente mediatizzazione della società. -

Both Principles and Men for Allegience and Truth Fatal Explosion at Ocean Grove Inspect Septic Tanks on Sun Day and Are Blown

Public Library Both Principles and Men For Allegience and Truth (INCORPORATED W ITH WHICH IS THE COAST ECHO) CIRCULATION BOOKS OPEN TO ALL VOL. XXIII.—Whole No. 1267. BELM A R , N. J., FR ID A Y , A P R IL 30, 1915 CIRCULATION BOOKS OPEN TO ALL Price Two Cents A carload of furniture has arrived in Visit to San Francisco Jo w l) Gossip and town for J. S. Watson who is thus early How the Women Earned Fatal Explosion preparing his splendid home at Inlet Ter Up and Down the What Churches are Makes One Proud of Home [ afest Happenings race for occupancy. Dollars for M. E. Church At Ocean Grove New Jersey Coast Doing in Belmar The remarks in the registration book in Joseph Mitchell, of Hackettstown visit The Dollar Social held by the Ladies’ the New Jersey Building is certainly in ed his son Charles C. Mitchell, principal Aid of the First Methodist church on Inspect Septic Tanks on Sun teresting and instructive. Many visitors Visitors Here and There and of the West Belmar school, for a few days News Notes Recorded in Tuesday night proved a success consider The Pastors Will Speak On , spend a lot of time reading the comments at his home 705 F street. ing the poor weather. A pleasing pro day and Are Blown lip and it affords them much pleasure. Peo Things Worth Mentioning Condensed Form gram had been prepared as follows: Appropriate Topics ple from all parts of the world have ex Borough Clerk Charles O. Hudnut went Vocal solo.................Miss Miriam Allgor pressed their appreciation of the New Jacob Schlosser has purchased a new to Princeton and spent the weekend with One of the most horrible accidents re R. -

Chc-2016-1614-Hcm Env-2016-1615-Ce

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2016-1614-HCM ENV-2016-1615-CE HEARING DATE: May 19, 2016 Location: 6201-6225 Sunset Blvd. TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 13 PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Hollywood 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA 90012 Neighborhood Council: Central Hollywood Legal Description: TR 11421, Lot 2 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the HOLLYWOOD PALLADIUM REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): CH Palladium, LLC Adam Tartakovsky, CH Palladium LLC 2200 Biscayne Blvd. 1800 Century Park East, Suite 420 Miami, FL 33137 Los Angeles, CA 90067 APPLICANT: City of Los Angeles Liza Brereton, Aids Healthcare Foundation 200 N. Spring Street, 559 6255 Sunset Blvd. 21st Floor Los Angeles, CA 90012 Los Angeles, CA 90028 PREPARER: Charles J. Fisher Christine Lazzaretto, HRG 140 S. Avenue 57 12 S. Fair Oaks Avenue, Suite 200 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Pasadena, CA 91105 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP Director of PlanningN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2016-1614-HCM 6201 - 6225 Sunset Blvd. -

The Dirty Immigrant Collective-Performers

Negin Farsad presents… THE DIRTY IMMIGRANT COLLECTIVE PERFORMERS’ NOTES Edinburgh Fringe 2010 This show has a variable line-up. NEGIN FARSAD www.neginfarsad.com www.youtube.com/neginfarsad www.twitter.com/neginfarsad - Director/executive producer of the current feature film release, “Nerdcore Rising,” a comedy about Nerdcore hip hop (premiered South By Southwest Film Festival, then toured other festivals winning Best Director, Best Film, and Audience Favourite along the way; now on distribution North America and France, and available on Netflix instant watch). - Directed and wrote the Comedy Central series, “The Watch List”. - Currently the Independent Film Channel's correspondent on all things interactive, tech and nerdy. - Currently writing for the forthcoming PBS animated series, “1001 Nights.” - Recently developed and wrote the MTV series, "Detox." - As a stand-up comedian Negin has opened for the likes of (Senator) Al Franken and Comedy Central’s Axis of Evil Comedy Tour in venues ranging from the Laugh Factory in New York, the Comedy Store in Los Angeles, and Town Hall on Broadway. - Negin has provided original comedy content for ABC Family as well as Pacifica and Sirius radio stations. - She has been an active comedian and producer, earning a nomination for the Emerging Comics of New York Awards. - Her solo show “Bootleg Islam”, which she wrote and performed, has appeared in multiple comedy festivals around the country culminating in an off-Broadway run in New York. - Winner Lifetime Woman Filmmaker Award for short film, “Hot Bread Kitchen”. - “Farsad has a touch of madness about her, and that's always worth the price of a ticket” – nytheatre.com - Two master's degrees from Columbia University where she studied public policy and race relations (degrees that now collect dust - ha ha). -

A History of the Middle of Georgia 1

Jackson: A History of the Middle of Georgia 1 In the southwestern section of town is a place that was once howling grounds for two packs of wolves. The two packs, one from Yellow Water and one from Sandy Creek, made that area their nocturnal meeting area and made nights frightful to early settlers due to the hideous howling. Before Jackson was created, the area where the downtown now stands was only two Indian trails that crossed where a 10’ by 12’ log cabin stood and was used as a post office. The first hanging in Jackson took place before the city was created in the middle of what would become Third Street between the Furlow and Slaughter residences. Two White men were hanged there on an old chestnut tree and were buried in the backyard of the Furlow place. 1818 In 1818, the first church services were held in what would become the City of Jackson. They were conducted by a Methodist, Mrs. Mary Williams Buttrill, in a log house erected by her slaves at what is now the east entrance to the Jackson Cemetery. Buttrill died in 1830, but for years she took her own seven boys, three daughters, slaves and local children into this log house one afternoon a week to hold religious services using her Bible and prayer book. 1822 The Southern Railway was built through the area that would soon become Butts County in 1822. A Western Union telegraph service came to the area soon after that. 1825 Butts County was created by an act of the Georgia General Assembly on December 24, 1825. -

Nathan J. Robinson Anatomy of a Monstrosity

“[Robinson] perfectly predicted what would happen in a Clinton-Trump race... He was one of the few pundits who did.” — FORTUNE TRUMP ANATOMY OF A MONSTROSITY NATHAN J. ROBINSON ANATOMY OF A MONSTROSITY TRUMP ANATOMY OF A MONSTROSITY By NATHAN J. ROBINSON Published by: Current Affairs Press P.O. Box 441394 W. Somerville, MA 02144 currentafairs.org Copyright © 2017 by Nathan J. Robinson All Rights Reserved First U.S. Edition Distributed on the West Coast by Waters & Smith, Ltd Monster City, CA ISBN 978-0997844771 No portion of this text may be reprinted without the express permission of Current Afairs, LLC. Cover photo copyright © Getty Images, reprinted with permission. Library of Congress Catalog-in-Publication Data Robinson, Nathan J. Trump: Anatomy of a Monstrosity / Nathan J. Robinson p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 978-0997844771 1. Trump, Donald J. 2. Political science 3. Elections 4. Social Philosophy 1. Title To all those who have had the misfortune of sharing a planet with Donald J. Trump, and to those who shall someday get rid of him and everything for which he stands. “We are here to help each other through this thing, whatever it is.” —Kurt Vonnegut “What kind of son have I created?” —Mary Trump, mother of Donald Trump1 CONTENTS Preface 13 Introduction: Trump U 19 I. Who He Is Te Life of Trump 37 Trump & Women 54 What Trump Stands For 69 Who Made Trump 97 II. How It Happened Trump the Candidate 111 Clinton v. Trump 127 What Caused It To Happen? 141 III. What It Means Despair Lingers 177 Orthodox Liberalism Has Been Repudiated 183 Te Press is Discredited Forever 199 Calamity Looms, or Possibly Doesn’t 211 Why Trump Must Be Defeated 217 IV. -

Shooting at San Diego-Area Synagogue Leaves 1 Dead, 3

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A News Briefs ............................... 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 43, NO. 35 MAY 3, 2019 28 NISAN, 5779 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ Holocaust Center wins tax grant The Holocaust Memorial Greater Orlando Chamber of Resource & Education Center Commerce building at the of Florida has been awarded northern gateway to down- a $10 million Orange County town Orlando. The site was Tourism Development Tax donated by the City of Orlando grant to build a new museum with a lease for the building in downtown Orlando. The and land for $1 per year. The award was announced Tues- new museum is expected to day, April 23 at the meeting draw 150,000 visitors annu- of the Orange County Board ally and contribute millions of County Commissioners. in economic impact to Central “We are thrilled and pro- Florida. foundly grateful to the leaders “It was an honor for me and of Orange County and the the Board of County Com- Tourist Development Tax missioners to unanimously Review Board for their vision award a $10 million grant and support. A new museum for the building of the Holo- will reach hundreds of thou- caust Museum for Hope and sands of visitors to our region Humanity. The museum will Gabrielle Birkner who increasingly seek more honor the victims and survi- Mourners leave mementos across the street from the Chabad Community Center in Poway, California a day after a meaningful and transforma- vors and serve as a historical shooter killed a congregant and wounded three others, on April 28, 2019. -

Global Nighttime Recovery Plan

GLOBAL NIGHTTIME RECOVERY PLAN CHAPTER 2: THE FUTURE OF DANCEFLOORS: BUILDING MORE FLEXIBLE, OPEN, AND INNOVATIVE CLUBBING EXPERIENCES 1 WHAT IS THE GLOBAL NIGHTTIME Suggestions for measuring progress: Both stories and data—quantitative and qualitative—are essential to capture progress and success in nightlife landscapes. RECOVERY PLAN? Harm-reduction mindset: We recognise that people will always want to gather. The Global Nighttime Recovery Plan is a collaborative practical guide that aims to Rather than denying that impulse, we wish to help people do so safely. This guide provide all members of the night-time ecosystem the knowledge and tools to aid their should always be used in the context of local public health guidelines. cities in planning for safe, intentional, and equitable re-opening. We hope this resource is of use in your city, and we’d love to hear how you’re putting Opportunities to Reimagine it to work. Please stay tuned at nighttime.org, and reach out to us with questions, ideas, and interest: [email protected]. Nighttime industries are facing unique pressures, but are also led by strategic and creative problem solvers and collaborative, resourceful organisers. By considering With warm wishes, both spatial and temporal dimensions of the 24-hour city, these cross-sector leaders The Global Nighttime Recovery Plan team can enable cities to rebound from COVID-19 stronger and more resilient than before. “WE’RE LIVING THROUGH A STRANGE AND RARE OPPORTUNITY Open-Air Nightlife and COVID-19: Managing TO BREAK AWAY FROM A BROKEN SYSTEM AND SECURE THE Learning As We Go: outdoor space and sound FOUNDATIONS OF A MORE SUSTAINABLE UNDERGROUND Gathering data and The Future of Dancefloors: measuring impact of Building more flexible, open, and CULTURE.” – CHAL RAVENS, FOR DJ MAG nightlife scenes through innovative clubbing experiences reopening and recovery Each chapter includes: GLOBAL Guidance from re-opening to re-imagination: NIGHTTIME 1.