Ijost Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALAN DE PELLETTE – Director | Producer | Writer

ALAN DE PELLETTE – Director | Producer | Writer Alan de Pellette is a director from Glasgow with wide ranging credits in TV and film. He began his career in radio and created the long running BBC Scottish comedy, OFF THE BALL, before moving into TV and a range of comedies for BBC Two, Three and BBC Scotland, including the award winning CHEWIN' THE FAT and the critically acclaimed OVERNITE EXPRESS & SHREDDED WEEK. Alan is currently producing a live action children’s television series of Julia Donaldson’s PRINCESS MIRROR BELLE for BBC Children’s Productions in Glasgow. As well as moving into drama, Alan has also made several documentaries for the BBC, including SCOTLAND'S GAME CHANGERS, which was nominated for both an RTS and Celtic Media Award in 2018. He has directed numerous single dramas, including MYSTIQUE NO 375, a children's drama for the BBC that screened in 15 countries around Europe during 2017 and 2018. In the last year, Alan has directed 15 episodes of Channel 4's ground breaking continuing drama, HOLLYOAKS, including major storylines on racism, far right grooming and domestic abuse. Alan has numerous film credits as a writer/director. His first short, THE AFICIONADO, was part of the UK Film Council scheme, '8½', under patron Peter Mullan. It screened in festivals around the world and is shown regularly on TV across Europe by Mini Movie Channel. He has made 4 other successful short films, including a 45’ portmanteau of connected stories, DECLARATIONS , inspired by the 60th anniversary of the UN Declarations of Human Rights. It premiered at the 2009 New York Independent Film Festival, where Alan won Best International Director. -

The Media, Poverty and Public Opinion in the UK

The media, poverty and public opinion in the UK John H. McKendrick, Stephen Sinclair, September 2008 Anthea Irwin, Hugh O’Donnell, Gill Scott and Louise Dobbie How the media in the UK represents poverty and its effect on wider public understanding. The media fulfi ls an important role in shaping, amplifying and responding to public attitudes toward poverty. This study, part of the ‘Public Interest in Poverty Issues’ research programme, explores the role of national, local and community media in refl ecting and infl uencing public ideas of poverty and welfare. The research aimed to: • compare representations of poverty across different contemporary UK media; • identify the principal factors and considerations infl uencing those involved in producing media coverage of poverty; • understand how UK media representations of poverty relate to the public’s understanding of poverty, and any differences between the responses of different groups; • identify examples of effective practice in communicating poverty issues to the public and derive transferable lessons from these. The researchers analysed coverage of poverty in news reporting; looked at how the same poverty news story was reported across different news outlets; reviewed how poverty was presented across different genres of television programme; interviewed key informants involved in the production, placement and presentation of poverty coverage in the mass media and explored public interpretations and responses to media coverage of poverty through focus groups/ workshops. www.jrf.org.uk Contents -

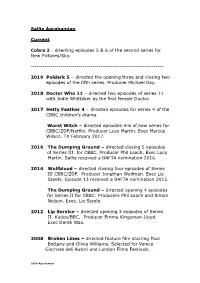

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2 - directing episodes 5 & 6 of the second series for New Pictures/Sky. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2019 Poldark 5 – directed the opening three and closing two episodes of the fifth series. Producer Michael Ray. 2018 Doctor Who 11 – directed two episodes of series 11 with Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor. 2017 Hetty Feather 4 – directed episodes for series 4 of the CBBC children’s drama. Worst Witch – directed episodes 4-6 of new series for CBBC/ZDF/Netflix. Producer Lucy Martin. Exec Marcus Wilson. TX February 2017. 2016 The Dumping Ground – directed closing 5 episodes of Series III for CBBC. Producer Phil Leach. Exec Lucy Martin. Sallie received a BAFTA nomination 2016. 2014 Wolfblood – directed closing four episodes of Series III CBBC/ZDF. Producer Jonathan Wolfman. Exec Lis Steele. Episode 13 received a BAFTA nomination 2015. The Dumping Ground – directed opening 4 episodes for Series II for CBBC. Producers Phil Leach and Simon Nelson. Exec. Lis Steele. 2012 Lip Service – directed opening 3 episodes of Series II. Kudos/BBC. Producer Emma Kingsman-Lloyd. Exec Derek Wax. 2008 Broken Lines – directed feature film starring Paul Bettany and Olivia Williams. Selected for Venice Giornate deli Autori and London Films Festivals. Sallie Aprahamian 2005 – 2009 The Bill – directed 8 episodes of the Thames/ITV series. Producers include Lachlan MacKinnon, Lis Steele and Ciara McIlvenny. 2003 Real Men – 2 x 90’ drama by Frank Deasy. Starring Ben Daniels. Producer David Snodin. Exec Frank Deasy and Barbara McKissack. BBC Scotland/BBC 2. RTS nomination. 2002 Outside the Rules – two part ‘Crime Double’ starring Daniela Nardini for BBC1/BBC Wales. -

Queer Television Thesis FINAL DRAFT Amended Date and Footnotes

Queer British Television: Policy and Practice, 1997-2007 Natalie Edwards PhD thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham School of American and Canadian Studies, January 2010 Abstract Representations of gay, lesbian, queer and other non-heterosexualities on British terrestrial television have increased exponentially since the mid 1990s. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer characters now routinely populate mainstream series, while programmes like Queer as Folk (1999-2000), Tipping the Velvet (2002), Torchwood (2006-) and Bad Girls (1999-2006) have foregrounded specifically gay and lesbian themes. This increase correlates to a number of gay-friendly changes in UK social policy pertaining to sexual behaviour and identity, changes precipitated by the election of Tony Blair’s Labour government in 1997. Focusing primarily on the decade following Blair’s installation as Prime Minister, this project examines a variety of gay, lesbian and queer-themed British television programmes in the context of their political, cultural and industrial determinants, with the goal of bridging the gap between the cultural product and the institutional factors which precipitated its creation. Ultimately, it aims to establish how and why this increase in LGBT and queer programming occurred when it did by relating it to the broader, government-sanctioned integration of gays, lesbians and queers into the imagined cultural mainstream of the UK. Unlike previous studies of lesbian, gay and queer film and television, which have tended to draw conclusions about cultural trends purely through textual analysis, this project uses government and broadcasting industry policy documents as well as detailed examination of specific television programmes to substantiate links between the cultural product and the wider world. -

Mckinney Macartney Management Ltd

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd LAURA MORROD – Editor FATE Director: Lisa James Larsson. Producer: Macdara Kelleher. Starring: Abigail Cowen, Danny Griffin and Hannah van der Westhuysen. Archery Pictures / Netflix. LOVE SARAH Director: Eliza Schroeder. Producer: Rajita Shah. Starring: Grace Calder, Rupert Penry-Jones, Bill Paterson and Celia Imrie. Miraj Films / Neopol Film / Rainstar Productions. THE LAST KINGDOM (Series 4) Director: Sarah O’Gorman. Producer: Vicki Delow. Starring: Alexander Dreymon, Ian Hart, David Dawson and Eliza Butterworth. Carnival Film & Television / Netflix. THE FEED Director: Jill Robertson. Producer: Simon Lewis. Starring: Guy Burnet, Michelle Fairlye, David Thewlis and Claire Rafferty. Amazon Studios. ORIGIN Director: Mark Brozel. Executive Producers: Rob Bullock, Andy Harries and Suzanne Mackie. Producer: John Phillips. Starring: Tom Felton, Philipp Christopher and Adelayo Adedayo. Left Bank Pictures. THE GOOD KARMA HOSPITAL 2 Director: Alex Winckler. Producer: John Chapman. Starring: Amanda Redman, Amrita Acharia and Neil Morrissey. Tiger Aspect Productions. THE BIRD CATCHER Director: Ross Clarke. Producers: Lisa Black, Leon Clarance and Ross Clarke. Starring: August Diehl, Sarah-Sofie Boussnina and Laura Birn. Motion Picture Capital. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 Laura Morrod Contd … 2 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: IN HIS OWN WORDS Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Des Shaw. Starring: Bruce Springsteen. Lonesome Pine Productions. HUMANS (Series 2) Director: Mark Brozel. Producer: Paul Gilbert. Starring: Gemma Chan, Colin Morgan and Emily Berrington. Kudos Film and Television. AFTER LOUISE Director: David Scheinmann. Producers: Fiona Gillies, Michael Muller and Raj Sharma. Starring: Alice Sykes and Greg Wise. -

Best Cities for Successful Aging” Is Not About the Best Every Five People Will Live in Cities, a Large Segment of Places to Retire

Sindhu Kubendran and Liana Soll Introduction by Paul Irving 2017 About the Milken Institute ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Milken Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank determined to I want to thank the authors of the 2017 “Best Cities for Successful increase global prosperity by advancing Aging” report and index, Sindhu Kubendran and Liana Soll. By collaborative solutions that widen access to capital, create jobs, and improve informing and educating civic leaders and the public, they are health. We do this through independent, improving lives in cities across America. I share their appreciation data-driven research, action-oriented for the data collection and research assistance of Maricruz Arteaga- meetings, and meaningful policy initiatives. Garavito as well as for the time and expertise of Jennifer Ailshire and Moosa Azadian of the University of Southern California. I’m grateful About the Center for the Future of Aging for the talents of our friend and project collaborator Rita Beamish, The mission of the Milken Institute Center for the sharp editorial eye of our colleague Edward Silver, and the visual the Future of Aging is to improve lives and strengthen societies by promoting healthy, acumen of our designer, Jane Lee. I appreciate Cheryl Murphy for her productive and purposeful aging. help in our Mayor’s Pledge campaign, Jill Posnick, Bridget Wiegman, and Tulasi Lovell for their communications support, and assistants @MIAging Shantika Maharaj and Fran Campione. Milken Institute researchers @MilkenCFA Ross DeVol and Perry Wong, along with fellow Anusuya Chatterjee, Future of Aging continue to support and contribute to the success of our “Best aging.milkeninstitute.org Cities” mission. -

1478 FELIX 14.01.11 the Student Voice of Imperial College London Since 1949

“Keep the Cat Free” ISSUE 1478 FELIX 14.01.11 The student voice of Imperial College London since 1949 Singapore medical Outdoor Club student New postgraduate halls VAT rise hits prices at school receives $150 breaks leg in 100ft fall at Clapham Junction Union bars million boost Union says students are “skilled, ex- 24-hour “concierge service” and free Becks to remain at £2 per pint but other Imperial’s venture with Nanyang Techno- perienced and equipped appropriately” on-site “fi tness” gym on offer at Griffon drinks see price hikes as Government logical University receives sizeable gift as questions about student safety are Studios. But at £235 per week, is the introduces controversial 2.5% VAT from the Lee Foundation. Page 4 raised. Page 5 price right? Page 5 increase. Page 9 College TECHNOLOGY considers 8am start Committee to look at timetable changes The latest gadgets Matt Colvin and innovation from In a move sure to raise eyebrows among those who prefer an extra hour (or three) CES 2011: Page 12 in bed, it has been revealed that a Col- lege committee is considering lengthen- ing the academic day in order to ensure that Imperial is able to “accommodate the growing number of master’s courses ARTS and extracurricular programmes [that it] offers.” The proposals being discussed include allowing teaching during the current lunch break by reducing it to one hour. Pro-Rector (Education and Academic Affairs) Professor Julia Buckingham confi rmed the plans to Felix, explaining SENATE that, “there is a committee looking at the ways that we can use our teaching space most effectively”. -

Mistletoes of North American Conifers

United States Department of Agriculture Mistletoes of North Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station American Conifers General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-98 September 2002 Canadian Forest Service Department of Natural Resources Canada Sanidad Forestal SEMARNAT Mexico Abstract _________________________________________________________ Geils, Brian W.; Cibrián Tovar, Jose; Moody, Benjamin, tech. coords. 2002. Mistletoes of North American Conifers. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–98. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 123 p. Mistletoes of the families Loranthaceae and Viscaceae are the most important vascular plant parasites of conifers in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Species of the genera Psittacanthus, Phoradendron, and Arceuthobium cause the greatest economic and ecological impacts. These shrubby, aerial parasites produce either showy or cryptic flowers; they are dispersed by birds or explosive fruits. Mistletoes are obligate parasites, dependent on their host for water, nutrients, and some or most of their carbohydrates. Pathogenic effects on the host include deformation of the infected stem, growth loss, increased susceptibility to other disease agents or insects, and reduced longevity. The presence of mistletoe plants, and the brooms and tree mortality caused by them, have significant ecological and economic effects in heavily infested forest stands and recreation areas. These effects may be either beneficial or detrimental depending on management objectives. Assessment concepts and procedures are available. Biological, chemical, and cultural control methods exist and are being developed to better manage mistletoe populations for resource protection and production. Keywords: leafy mistletoe, true mistletoe, dwarf mistletoe, forest pathology, life history, silviculture, forest management Technical Coordinators_______________________________ Brian W. Geils is a Research Plant Pathologist with the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Flagstaff, AZ. -

BBC SCOTLAND 2007/2008 BBC Scotland Executive Report

BBC SCOTLAND 2007/2008 BBC Scotland Executive Report 1 Contents Controller’s Overview 2 Television 3 Radio 6 Online & Multiplatform 8 News & Current Affairs 10 Gaelic 12 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra 14 Children in Need 16 Facts & Figures 17 Get in touch 18 Cover: Mountain Above: Still Game 1 Controller’s Overview Ken MacQuarrie Controller, BBC Scotland When I wrote my Controller’s Overview last year I did so Scottish Broadcasting Commission have seen broadcasting having just moved into our new headquarters at Pacifi c Quay move further into the public spotlight. I fi rmly believe that BBC in Glasgow. Our offi cial opening soon followed and, in the ten Scotland is entering a period of production growth. It has an months since then, we have started to realise some of the important contribution to make to Scotland’s creative sector incredible potential of this building. Indeed many thousands and for that reason I very much welcome the public debate have already been able to attend numerous large scale live which is currently focussed on broadcasting. events right here at Pacifi c Quay in a way that was not possible in Queen Margaret Drive. Now settled in at Pacifi c Quay, we are pushing to deliver a wide variety of creative content from our production centres Although this happened at a time when the BBC as a whole across Scotland over the next few years. In drama, comedy was having to be as effi cient as possible, following the smaller and entertainment, children’s, factual, sport and news, our than expected licence fee settlement, I was excited by the production teams are working on a diverse range of different prospect of creating great content for audiences in Scotland projects for audiences. -

Caroline Cornish Management

CAROLINE CORNISH MANAGEMENT 12 SHINFIELD STREET, LONDON W12 OHN Tel: 44 (0) 20 8743 7337 Mobile: 44 (0) 7725 555711 e-mail: [email protected] www.carolinecornish.co.uk CLAIRE LYNCH - COSTUME DESIGNER Countries worked in: France, Germany, Morocco, Spain Language spoken: French and Spanish CALL THE MIDWIFE 11 Directors: Annie Tricklebank, Noreen Kershaw, Thomas Hescott Christmas Special: Syd Macartney CALL THE MIDWIFE 10 Directors: Annie Tricklebank, Noreen Kershaw, Thomas Hescott, David O’Neill, Sarah Ersdaile, James Larkin, Syd Macartney Producers: Annie Tricklebank, Heidi Thomas, Pippa Harris THE MALLORCA FILES 2 Production Suspended due to Coronavirus 10pt drama series Directors: Bryn Higgins, Rob Evans, Craig Pickles, Mallorca Christina Ebohon-Green Producer: Dominic Barlow Prod Co: Clerkenwell Films/BBC Featuring: Maria Fernandez Ache, Julian Looman, Elen Rhys, CALL THE MIDWIFE 9 Directors: Syd Macartney, Kate Cheeseman, David O’Neill Noreen Kirkshaw Producer: Annie Trickleback, Pippa Harris Directors: Syd Macartney, Annie Tricklebank, David O’Neill, Noreen Kershaw, Afia Nkrumah, Thomas Hescott BAGHDAD CENTRAL Director: Ben Williams Ep. 4, 5, 6 Producer: Jonathan Curling Shot in Morocco CALL THE MIDWIFE 8 Directors: Christiana Ebohon, Kate Cheesman, Kate Saxon, Syd Macartney Producers: Annie Tricklebank, Heidi Thomas, Pippa Harris Prod Co: Neal Street Productions/BBC Featuring: Annabelle Apison, Annette Crosbie, Ann Mitchell, Cliff Parisi, Helen George, Jennifer Kirby, Jenny Agutter, Judy Parfitt, Laura Main, Leonie Elliot, Linda -

Straub Medical Center Community Health Needs Assessment

Straub Medical Center Community Health Needs Assessment — March 2016 — Produced by Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................... vi Introduction ....................................................................................................... vi Summary of Findings ......................................................................................... vi Selected Priority Areas .................................................................................... viii 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Summary of CHNA Report Objectives and Context ...................................... 1 1.2 About the Hospital ....................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 Definition of Community + Map ........................................................... 2 1.2.2 Hawai‘i Pacific Health .......................................................................... 2 1.3 Healthcare Association of Hawaii ............................................................... 2 1.3.1 Member Hospitals................................................................................. 3 1.4 Advisory Committee ................................................................................... 3 1.5 Consultants ................................................................................................. 4 1.5.1 Healthy Communities Institute -

The Media, Poverty and Public Opinion in the UK

The media, poverty and public opinion in the UK John H. McKendrick, Stephen Sinclair, September 2008 Anthea Irwin, Hugh O’Donnell, Gill Scott and Louise Dobbie How the media in the UK represents poverty and its effect on wider public understanding. The media fulfi ls an important role in shaping, amplifying and responding to public attitudes toward poverty. This study, part of the ‘Public Interest in Poverty Issues’ research programme, explores the role of national, local and community media in refl ecting and infl uencing public ideas of poverty and welfare. The research aimed to: • compare representations of poverty across different contemporary UK media; • identify the principal factors and considerations infl uencing those involved in producing media coverage of poverty; • understand how UK media representations of poverty relate to the public’s understanding of poverty, and any differences between the responses of different groups; • identify examples of effective practice in communicating poverty issues to the public and derive transferable lessons from these. The researchers analysed coverage of poverty in news reporting; looked at how the same poverty news story was reported across different news outlets; reviewed how poverty was presented across different genres of television programme; interviewed key informants involved in the production, placement and presentation of poverty coverage in the mass media and explored public interpretations and responses to media coverage of poverty through focus groups/ workshops. www.jrf.org.uk Contents