Full Text Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution De Jeux Et Jouets

IndexPresse Business Etude Secteurs & marchés Distribution de jeux et jouets Face à la domination des grandes surfaces et à la hausse de l’e-commerce, quel nouveau modèle pour le circuit spécialisé ? secteurs & marchés Distribution de jeux et jouets Face à la domination des grandes surfaces et à la hausse de l’e-commerce, quel nouveau modèle pour le circuit spécialisé ? ntre 2013 et 2018, la part des spécialistes de la distribution de jeux et jouets en France s’est for te- ment contractée sous l’effet de la progression du circuit de l’e-commerce. Auparavant immuable et solide, le secteur fait désormais face à une décélération des ventes et à une transformation du Epaysage de la distribution. Les redressements judiciaires de l’américain Toys’R’Us et de l’enseigne française La Grande Récré ali- mentent les inquiétudes des experts et des professionnels. La distribution spécialisée de jeux et jouets s’interroge sur son avenir. Fondé sur les codes anciens du commerce physique, son modèle doit être repensé pour répondre aux nouvelles attentes des consommateurs, sans renier pour autant les forces qui ont fait son succès. Les enseignes agissent pour asseoir leur ancrage local tout en investissant la sphère numérique. Les réseaux continuent de se développer. Les formats s’ajustent. Le multicanal s’impose. Face à la guerre des prix instaurée par les pure players de l’e-commerce et les grandes surfaces alimen- taires (GSA), il s’agit pour le circuit spécialisé de miser sur ses qualités propres pour faire la différence. L’expertise, la précision de l’offre et la relation de proximité doivent s’imposer pour développer le lien émotionnel qui le rapproche de ses clients. -

Marvel Universe by Hasbro

Brian's Toys MARVEL Buy List Hasbro/ToyBiz Name Quantity Item Buy List Line Manufacturer Year Released Wave UPC you have TOTAL Notes Number Price to sell Last Updated: April 13, 2015 Questions/Concerns/Other Full Name: Address: Delivery Address: W730 State Road 35 Phone: Fountain City, WI 54629 Tel: 608.687.7572 ext: 3 E-mail: Referred By (please fill in) Fax: 608.687.7573 Email: [email protected] Guidelines for Brian’s Toys will require a list of your items if you are interested in receiving a price quote on your collection. It is very important that we Note: Buylist prices on this sheet may change after 30 days have an accurate description of your items so that we can give you an accurate price quote. By following the below format, you will help Selling Your Collection ensure an accurate quote for your collection. As an alternative to this excel form, we have a webapp available for http://buylist.brianstoys.com/lines/Marvel/toys . STEP 1 Please note: Yellow fields are user editable. You are capable of adding contact information above and quantities/notes below. Before we can confirm your quote, we will need to know what items you have to sell. The below list is by Marvel category. Search for each of your items and enter the quantity you want to sell in column I (see red arrow). (A hint for quick searching, press Ctrl + F to bring up excel's search box) The green total column will adjust the total as you enter in your quantities. -

Hasbro Closes Acquisition of Saban Properties' Power Rangers And

Hasbro Closes Acquisition of Saban Properties’ Power Rangers and other Entertainment Assets June 12, 2018 PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jun. 12, 2018-- Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS) today announced it has closed the previously announced acquisition of Saban Properties’ Power Rangers and other Entertainment Assets. The transaction was funded through a combination of cash and stock valued at $522 million. “Power Rangers will benefit from execution across Hasbro’s Brand Blueprint and distribution through our omni-channel retail relationships globally,” said Brian Goldner, Hasbro’s chairman and chief executive officer. “Informed by engaging, multi-screen entertainment, a robust and innovative product line and consumer products opportunities all built on the brand’s strong heritage of teamwork and inclusivity, we see a tremendous future for Power Rangers as part of Hasbro’s brand portfolio.” Hasbro previously paid Saban Brands$22.25 million pursuant to the Power Rangers master toy license agreement, announced by the parties in February of 2018, that was scheduled to begin in 2019. Those amounts were credited against the purchase price. Upon closing, Hasbro paid $131.23 million in cash (including a $1.48 million working capital purchase price adjustment) and $25 million was placed into an escrow account. An additional $75 million will be paid on January 3, 2019. These payments are being funded by cash on the Company’s balance sheet. In addition, the Company issued 3,074,190 shares of Hasbro common stock to Saban Properties, valued at $270 million. The transaction, including intangible amortization expense, is not expected to have a material impact on Hasbro’s 2018 results of operations. -

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist Series 1 - Fury Files Wave 1 • 001 - Iron Man (Modern Armor) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Light Paint Variant) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Dark Paint Variant) • 003 - Silver Surfer • 004 - Punisher • 005 - Black Panther • 006 - Wolverine (X-Force costume) • 007 - Human Torch (Flamed On) • 008 - Daredevil (Light Red Variant) • 008 - Daredevil (Dark Red Variant) • 009 - Iron Man (Stealth Ops) • 010 - Bullseye (Light Paint Variant) • 010 - Bullseye (Dark Paint Variant) • 011 - Human Torch (Light Blue Costume) • 011 - Human Torch (Dark Blue Costume) Wave 2 • 012 - Captain America (Ultimates) • 013 - Hulk (Green) • 014 - Hulk (Grey) • 015 - Green Goblin • 016 - Ronin • 017 - Iron Fist (Yellow Dragon) • 017 - Iron Fist (Black Dragon Variant) Wave 3 • 018 - Black Costume Spider-Man • 019 - The Thing (Light Pants) • 019 - The Thing (Dark Pants) • 020 - Punisher (Modern Costume & New Head Sculpt) • 021 - Iron Man (Classic Armor) • 022 - Ms. Marvel (Modern Costume) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Carol Danvers) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Karla Sofen) • 024 - Hand Ninja (Red) Wave 4 • 026 - Union Jack • 027 - Moon Knight • 028 - Red Hulk • 029 - Blade • 030 - Hobgoblin Wave 5 • 025 - Electro • 031 - Guardian • 032 - Spider-man (Red and Blue, right side up) • 032 - Spider-man (Black and Red, upside down Variant) • 033 - Iron man (Red/Silver Centurion) • 034 - Sub-Mariner (Modern) Series 2 - HAMMER Files Wave 6 • 001 - Spider-Man (House of M) • 002 - Wolverine (Xavier School) -

Masters of the Universe: Action Figures, Customization and Masculinity

MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE: ACTION FIGURES, CUSTOMIZATION AND MASCULINITY Eric Sobel A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2018 Committee: Montana Miller, Advisor Esther Clinton Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Montana Miller, Advisor This thesis places action figures, as masculinely gendered playthings and rich intertexts, into a larger context that accounts for increased nostalgia and hyperacceleration. Employing an ethnographic approach, I turn my attention to the under-discussed adults who comprise the fandom. I examine ways that individuals interact with action figures creatively, divorced from children’s play, to produce subjective experiences, negotiate the inherently consumeristic nature of their fandom, and process the gender codes and social stigma associated with classic toylines. Toy customizers, for example, act as folk artists who value authenticity, but for many, mimicking mass-produced objects is a sign of one’s skill, as seen by those working in a style inspired by Masters of the Universe figures. However, while creativity is found in delicately manipulating familiar forms, the inherent toxic masculinity of the original action figures is explored to a degree that far exceeds that of the mass-produced toys of the 1980s. Collectors similarly complicate the use of action figures, as playfully created displays act as frames where fetishization is permissible. I argue that the fetishization of action figures is a stabilizing response to ever-changing trends, yet simultaneously operates within the complex web of intertexts of which action figures are invariably tied. To highlight the action figure’s evolving role in corporate hands, I examine retro-style Reaction figures as metacultural objects that evoke Star Wars figures of the late 1970s but, unlike Star Wars toys, discourage creativity, communicating through the familiar signs of pop culture to push the figure into a mental realm where official stories are narrowly interpreted. -

Vtech/Leapfrog Initial Submission

Completed Acquisition by VTech Holdings Limited of LeapFrog Enterprises Inc. Initial Submission to the Competition and Markets Authority 11 October 2016 i ii Table of Contents Contents Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 2 I.1 No realistic counterfactual scenario, let alone the most likely one, is substantially more competitive than the post-Transaction outcome ..................................................................... 3 I.2 In any event, the Transaction fails to raise substantive issues even against a more typical counterfactual .......................................................................................................................... 4 I.3 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 9 II. THE PARTIES ....................................................................................................................... 10 II.1 VTech .................................................................................................................................... 10 II.2 LeapFrog ............................................................................................................................... 12 III. THE TRANSACTION ............................................................................................................ 14 III.1 Transaction structure ............................................................................................................ -

Merchandising, Transmediality and Nostalgia in Power Rangers Super Megaforce Ross P

[email protected] @DefConG Going Legendary: Merchandising, Transmediality and Nostalgia in Power Rangers Super Megaforce Ross P. Garner School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies Cardiff University Introduction • Research questions: • How do forms of nostalgia become constructed in programmes primarily targeting children? • What cultural issues do these industrially-located strategies intersect with? • Approach taken: • Nostalgia as discourse. • Addressing social, cultural, historical and industrial contexts. • Case study: • Power Rangers Super Megaforce (Saban Brands 2014) Introducing Legendary Mode Diegetic Codings of Objects Decontextualized Nostalgia Decontextualized Nostalgia and Imagined Audiences • Audiences targeted: • Fans • ‘Child’ = primary audience: • “Boys aged 4-8” (Saban Brands 2013: 2) • “As they get older, children repeatedly (and often fiercely) reject their former enthusiasms: differences of as little as a couple of years carry enormous significance.” (Buckingham and Sefton- Green 2004: 15). • Adults: • Intertextual pleasures (Gordon 2003) • Inter-generational bridging. Decontextualized Nostalgia, Adults and Reassurance • Useful framework = Giddens (1991)…: • Trust in abstract systems = subjective anxiety and powerlessness. • Counter this through reflexive self-narratives and ontological security. • …but add to this: • Davis (1979: 41) on nostalgia and self-identity. • Holdsworth (2011) – TV rememberance = show and context. • Discourses constructing the Power Rangers: • Violence; consumerist; aesthetic dismissals -

POLICE COURT out New Schemes Qtf‘Traffle Regula T*Rr? Tion

trm . ' ■ • j . •. t ■ ■ J ' '-I ;"i ■....' v-v iiTiv?. TBE WEATHER NET PRESS RUM ■ . - ,.V(5 PcrMMrt br 0> t. Waatber ; Barcaa.'-. ,. ’"it AVERAGE DAULV CtROULATION N«tc ipavea: . tor tho month Of April. 1Q2W • -.•r- .;* v Local showers tonli^t and Fii^ 5,128 day. , HsialMV « t tk<i Aatflt UaMpa of OtrmUalloan * (FOURTEEN PAGES) PiUCE THREE CENTS VOL. X U I., NO. 195. Classified Advertising on Page 12. MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY^ MAY 17, 1928. .\ STATEtOFC. OSTON POLICE Coolidge at Historical Pageant MAKES A PLEA To Friance, The Reason ARE INVOLVED MARCH ON PEKING; FOR m n o N Paris, May 17.— Great has been^put the people right. IN BIG PROBE the surprise and bewilderment of i “ No, the United States is not the French people to learn that paying any debt to France, for she RED $92,000,000 in gold bas been re- owes us nothing," announced the Wants Landing Fields in All celvfd In Parik from New York bank. “ This gold represents dollars A Member of Ibe Rum and since the beginning of the year and ' pur'chased by the Bank of France that there is still $60,000,000 to in America at the beginning 'of Foreign Troops Guard Em- Com m unities^ Uniform come from America later in the 1927 and ‘earmarked’ for France. Graft Ring, Now in Jail METHODIST BISHOP year. "After all these shipments are “ I did not know that America nothing more than a transfer from b a ssie s^ o y ie t Soldiers Parking Laws Suggested owed us-that much,” is one of the one vault to another. -

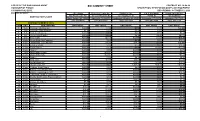

Bid Summary Sheet Contract No

OFFICE OF THE PURCHASING AGENT BID SUMMARY SHEET CONTRACT NO. 14-04-24 TOWNSHIP OF EDISON DESCRIPTION: RECREATION GAMES AND EQUIPMENT 100 MUNICIPAL BLVD. BID OPENING: OCTOBER 10, 2014 EDISON, NJ 08817 ARC Sports Metuchen Center Inc. Flaghouse Inc. S & S Worldwide School Specialty Inc. 850 Peach Lake Rd 10-12 Embroidery St 601 Flaghouse Dr 75 Mill St 140 Marble Dr CONTRACTOR'S NAME North Salem, NY 10560 Sayreville, NJ 08872 Hasbrouck Heights, NJ 07604 Colchester, CT 06415 Lancaster, PA 17601 (203) 775-4140 (732) 418-1388 (800) 793-7900 (800) 642-7354 (888) 388-3224 CONTRACT EXPIRES:1/9/16 ITEM UNIT DESCRIPTION UNIT PRICE UNIT PRICE UNIT PRICE UNIT PRICE UNIT PRICE 1 Sets Checkers (No Boards) NO BID $1.65 $1.53 $1.76 NO BID 2 Sets Checkers (With Boards) $2.75 $2.75 $3.34 $3.07 $2.58 3 Sets Chinese Checkers NO BID $2.95 $4.61 $9.10 $3.56 4 Dz Chess Sets (Plastic) NO BID $35.00 $4.18 $56.40 $43.32 5 Sets Bocci Balls NO BID $21.95 NO BID $12.00 $11.98 6 Each Koosh Balls (No Paddles) NO BID $2.95 $2.12 $2.46 $13.46 7 Each Ladder Ball Toss (Blongo) NO BID $21.50 $27.29 $21.00 NO BID 8 Each Hackey Sacks NO BID $2.95 $2.52 $1.76 $11.98 9 Each Potato Sacks NO BID $2.00 $1.00 * $14.64 * $13.24 10 Each "Skip It" NO BID $5.50 NO BID $1.40 $9.73 11 Pairs Magic Mitts & Balls NO BID NO BID NO BID $5.70 $4.30 12 Each Magic Mitts Balls NO BID NO BID NO BID $1.32 *$5.38 13 Each Frisbee NO BID $3.95 $6.11 $1.00 $4.67 14 Each Ring Toss NO BID $11.95 $10.07 $9.80 $10.86 15 Each Hoola Hoops 30" NO BID $1.95 *$36.97 * $24.48 * $16.25 16 Each Hoola Hoops 36" NO BID $2.25 * $47.74 * $30.96 * $17.72 17 Each Chinese Jump Ropes NO BID $2.95 $2.58 $1.13 $8.63 18 Each Rubber Jump Ropes-9 ft. -

Women in Toys Recognizes Industry Innovators at Annual Awards Gala

WOMEN IN TOYS RECOGNIZES INDUSTRY INNOVATORS AT ANNUAL AWARDS GALA Mattel Honored with Game Changer Award; Hasbro, SpinMaster, Moose Toys and Walmart Top Winners New York City – February 15, 2016 – More than 500 executives in toys, licensing and entertainment gathered Sunday night to honor women leaders at the 12th Annual Wonder Women Awards Gala, Celebrating 25 Years of Women in Toys in New York City. The event, hosted by leading global organization for professional women in the toy, licensing and children’s entertainment industry, Women in Toys (WIT), awarded 12 distinguished winners from over 50 nominees from around the world. Among the Wonder Women Gala Award Winners, WIT presented awards to special honorees that included the: Founders Award to Anne Pitrone and Susan Matsumoto who created WIT 25 years ago. Started in a restaurant over the quarter century, the professional group has grown to service thousands of professionals from around the globe at more than 50 events annually. Game Changer Award to Mattel for the evolution of its Barbie brand with the recent expansion of the Barbie Fashionistas. The award was presented by fashion and celebrity stylist Micaela Erlanger, and globally recognized advocate for positive body image and self-esteem supermodel EMME. Wonder Girl Award to Sydney and Toni Loew, two young toy making entrepreneurs and the creators of Poketti pocket plush. Wonder Women Awards Gala Winners Manufacturer, Cat Demas, Vice President & Global Business Head, Preschool Girls Spin Master Rising Star, Laura Guilbault, Director of Product & Marketing Strategy for Disney Princess and Frozen, Hasbro Public Relations, Tara Tucker, Vice President of Global Marketing Communications, Spin Master Designer / Inventor, Jacqui Tobias, Director and Head of Girls Product Development, Moose Toys Licensing & Entertainment, Joan Grasso, Vice President of Licensing North America, Entertainment One Marketing, Kimberly Willis Boyd, Vice President of U.S. -

FBIC Global Holiday 2014 Hottest Toys Nov. 15

November 15, 2014 NOVEMBER 15, 2014 DEBORAH WEINSWIG, Executive Director Head Global Retail Research and Intelligence Fung Business Intelligence Centre FBIC Global publication: Holiday 2014’s Hottest Toys [email protected] New York: 646.839.7017 1 November 15, 2014 Holiday 2014’s Hottest TOYS It’s the most wonderful time of the year!! It’s November 15 and the most wonderful time of the year is just getting started. A big part of the magic of the season is seeing kids eyes light up when they open a holiday gift to find their favorite toy from their wish list. What are kids asking for this year? Some of the most desired qualities are tactile, electronic, do-it-yourself, and education made fun. We’ve taken a look at the top toy lists of five major retailers—Toys R Us, Amazon, Target, Kmart and Walmart—and looked at recent events with major toy companies including Mattel and Legos, to give you some shopping insight for the season. These are the toys we think will be hot sellers this season. Most of our toy picks are for kids age 12 and under (because truthfully, after age 12 what kids really want is an iPhone 6.) HOLIDAY 2014 HOT TOY LIST Top 5 Electronics for Kids 1. Disney’s Frozen Snow Glow Elsa Singing Doll 1. Amazon Fire HD, Kids Edition 2. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Battle Shell 2. iPad Mini 3 for kids Leonardo Action Figure 3. Kurio Xtreme tablet for kids 3. Doc McStuffins Get Better Talking Mobile Cart 4. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th.