1994 A1 Fedra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signing the Body Dramatic Interpretation and Translation of Racine's Phedre

Signing the Body Dramatic Interpretation and Translation of Racine's Phedre An undergraduate thesis in Theater and Linguistics by Emily Louise Melnick K. Elizabeth Stevens & DonnaJo Napoli Swarthmore College, Swarthmore Pennsylvania April 29, 2012 Table of Contents 2 Introduction 5 Two Brief Notes 6 Excerpts from Storytelling as a Means ofCulturalAffirmation 12 Culture Swapping 14 What is Deaf Theater? 16 Getting Started 20 What's in a Name? 27 The Matter of Meter 33 Issues and Errata 39 Introduction to ASL Gloss 42 Phedre, PHEDRE, P-H-E-D-R-E: Act I 54 Racine's Phedre: Acte I 1 Introduction And ifthe body does not do fully as much as the soul? And ifthe body were not the soul, what is the soul? -Walt Whitman, I Sing the Body Electric American Sign Language is a language of the body. It's a language of gesture, of facial expression, of sight and touch. As an actor, a linguist, and a dramaturg (and one who was raised on a heavy diet of Brecht's Epic Theater), I'm drawn to ASL as a medium for theater, for storytelling, and for connection and communication. This thesis is an exploration of my experiences with ASL as a literary and theatrical medium-my experiments in ASL translation, my understanding of Deaf theater, and my musings on communication, translation, and creation. The thesis is naturally bipartite. ASL being a highly visual, four-dimensional language, my translation work is presented in video format. The paper (or, more likely, pixel) portion of my thesis is a window into my process. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 47,1927

CARNEGIE HALL .... NEW YORK Thursday Evening, November 24, at 8.30 Saturday Afternoon, November 26, at 2.30 / III WWllillJI/// ^ :%. m 4f- & BOSTON v %ro SYAPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. FORTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1927-1928 PRSGR7W\E " . the mechanism is so perfect as to respond to any demand and, in fact, your piano ceases to be a thing of ivocd and -wires, but becomes a sympathetic friend." Wt^ Wilhelm BachailS, most exacting of pianists, finds in the Baldwin the perfect medium of musical ex- pression. Acclaimed the pianist of pianists, beloved by an ever-growing public, Bachaus has played the Baldwin exclusively for twelve years, in his home and on all his American tours. That loveliness and purity of tone which appeals to Bachaus and to every exacting musician is found in all Baldwins; alike in the Concert Grand, in the smaller Grands, in the Uprights. The history of the Baldwin is the history of an ideal. ^albtotn $tano Company 20 EAST 54th STREET NEW YORK CITY CARNEGIE HALL - - - NEW YORK Forty-second Season in New York FORTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1927-1928 INC. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor m©^ the THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 24, at 8.30 AND THE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 26, at 2.30 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1927, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President BENTLEY W. WARREN Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE Treasurer FREDERICK P. CABOT FREDERICK E. LOWELL ERNEST B. DANE ARTHUR LYMAN N. PENROSE HALLOWELL EDWARD M. PICKMAN M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE HENRY B. -

Medea De Eurípides: El Personaje Y El Conflicto Trágico. Lecturas Filosóficas

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE ROSARIO FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y ARTES ESCUELA DE POSGRADO Medea de Eurípides: el personaje y el conflicto trágico. Lecturas filosóficas TESIS PRESENTADA PARA LA OBTENCIÓN DEL GRADO DE DOCTOR EN HUMANIDADES Y ARTES, MENCIÓN FILOSOFÍA DIRECTORA: DRA. SILVANA FILIPPI DOCTORANDA: LIC. MARCELA CORIA Septiembre 2013 Agradecimientos En primer lugar, quisiera expresar mi sincero y profundo agradecimiento a mi Directora, la Dra. Silvana Filippi, no sólo por la confianza depositada en mí, su constante guía y aliento durante varios años, que hicieron que esta tarea fuera un poco menos solitaria, sino también por su rigurosidad, su seguimiento, sus sugerencias y sus correcciones. Su sólida experiencia y su excepcional calidad humana han sido para mí inestimables. Estoy convencida de que sin sus permanentes palabras y consejos, tanto de índole académica como personal, este trabajo no hubiese podido llegar a término. Deseo expresar, además, mi gratitud hacia el Dr. Rodrigo Braicovich, por su asesoramiento informático y bibliográfico; el Dr. Marcelo D. Boeri, por sus orientaciones en las primeras etapas de este trabajo; el personal de la Escuela de Posgrado de esta Facultad, por su calidez y eficiencia; y la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, una institución que me ha brindado todo su apoyo para realizar este posgrado. Quiero también manifestar mi agradecimiento a mi querida amiga y colega la Dra. Soledad Correa, quien leyó minuciosamente varias partes de este trabajo y discutió conmigo algunas de las ideas vertidas aquí. A su sincera amistad y apoyo incondicional a lo largo de todo este laborioso proceso no puedo pretender hacerles debida justicia en estas breves líneas. -

Of Titles (PDF)

Alphabetical index of titles in the John Larpent Plays The Huntington Library, San Marino, California This alphabetical list covers LA 1-2399; the unidentified items, LA 2400-2502, are arranged alphabetically in the finding aid itself. Title Play number Abou Hassan 1637 Aboard and at Home. See King's Bench, The 1143 Absent Apothecary, The 1758 Absent Man, The (Bickerstaffe's) 280 Absent Man, The (Hull's) 239 Abudah 2087 Accomplish'd Maid, The 256 Account of the Wonders of Derbyshire, An. See Wonders of Derbyshire, The 465 Accusation 1905 Aci e Galatea 1059 Acting Mad 2184 Actor of All Work, The 1983 Actress of All Work, The 2002, 2070 Address. Anxious to pay my heartfelt homage here, 1439 Address. by Mr. Quick Riding on an Elephant 652 Address. Deserted Daughters, are but rarely found, 1290 Address. Farewell [for Mrs. H. Johnston] 1454 Address. Farewell, Spoken by Mrs. Bannister 957 Address. for Opening the New Theatre, Drury Lane 2309 Address. for the Theatre Royal Drury Lane 1358 Address. Impatient for renoun-all hope and fear, 1428 Address. Introductory 911 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of Drury Lane Theatre 1827 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of the Hay Market Theatre 2234 Address. Occasional. In early days, by fond ambition led, 1296 Address. Occasional. In this bright Court is merit fairly tried, 740 Address. Occasional, Intended to Be Spoken on Thursday, March 16th 1572 Address. Occasional. On Opening the Hay Marker Theatre 873 Address. Occasional. On Opening the New Theatre Royal 1590 Address. Occasional. So oft has Pegasus been doom'd to trial, 806 Address. -

The Mythological Image of the Prince in the Comedia of the Spanish Golden Age

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2014 STAGING THESEUS: THE MYTHOLOGICAL IMAGE OF THE PRINCE IN THE COMEDIA OF THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE Whitaker R. Jordan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jordan, Whitaker R., "STAGING THESEUS: THE MYTHOLOGICAL IMAGE OF THE PRINCE IN THE COMEDIA OF THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/15 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Yes, Virginia, Another Ballo Tragico: the National Library of Portugal’S Ballet D’Action Libretti from the First Half of the Nineteenth Century

YES, VIRGINIA, ANOTHER BALLO TRAGICO: THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF PORTUGAL’S BALLET D’ACTION LIBRETTI FROM THE FIRST HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ligia Ravenna Pinheiro, M.F.A., M.A., B.F.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Karen Eliot, Adviser Nena Couch Susan Petry Angelika Gerbes Copyright by Ligia Ravenna Pinheiro 2015 ABSTRACT The Real Theatro de São Carlos de Lisboa employed Italian choreographers from its inauguration in 1793 to the middle of the nineteenth century. Many libretti for the ballets produced for the S. Carlos Theater have survived and are now housed in the National Library of Portugal. This dissertation focuses on the narratives of the libretti in this collection, and their importance as documentation of ballets of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, from the inauguration of the S. Carlos Theater in 1793 to 1850. This period of dance history, which has not received much attention by dance scholars, links the earlier baroque dance era of the eighteenth century with the style of ballet of the 1830s to the 1850s. Portugal had been associated with Italian art and artists since the beginning of the eighteenth century. This artistic relationship continued through the final decades of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century. The majority of the choreographers working in Lisbon were Italian, and the works they created for the S. Carlos Theater followed the Italian style of ballet d’action. -

Opéras & Oratorios

CD (en rouge Opéra Magazine) Opéras & oratorios Abencérages (Les) Giulini (Gala) 268/69 - Maag (Arts) 11/74 Abu Hassan Weil (DHM) 285/73 Aci e Galatea (Naumann) Bernius (Orfeo) 276/69 Acide Huss (Bis) 41/75 Acis and Galatea (Haendel) Christie (Erato) 238/71 - Haïm (Virgin) 280/69 - McGegan (Carus) 42/79 - Butt (Linn) 42/79 Acis y Galatea (Literes) Lopez Banzo (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi) 257/68 Actéon O’Dette/Stubbs (CPO) 63/78 Adelaide di Borgogna Carella (Opera Rara) 15/72 Adelia Neschling (Ricordi) 244/73 - Kuhn (RCA) 23/73 Admetus Lewis (Ponto) 299/106 Adriana Lecouvreur Rossi (Hardy Classic) 251/60 - Masini (Gala) 251/61 - Masini (Myto) 251/61 - Gavazzeni (Myto) 273/68 - Del Cupolo (VAI) 296/79 - Bonynge (Decca) 12/77 - De Fabritiis (Testament) 107/76 Adriano in Siria Biondi (Fra Bernardo) 106/81 - Adamus (Decca) 122/75 Adrien Vashegyi (Ediciones Singulares/Palazzetto Bru Zane) 98/81 Affaire Makropoulos (L’) Mackerras (Decca) 02/13 - Mackerras (Chandos) 24/77 Agrippina Malgoire (Dynamic) 290/84 - Jacobs (Harmonia Mundi) 67/71 Ägyptische Helena (Die) Krips (RCA) 243/64 - Korsten (Dynamic) 265/70 Aida Molajoli (VAI) 258/68 - De Sabata (Eklipse) 258/68 - Keilberth (Preiser) 258/68 - Beecham (Arkadia) 258/68 - Panizza (Walhall) 258/68 - Pelletier (GOP) 258/68 - Serafin (EMI) 258/68 - Karajan (Arkadia) 258/68 - Cleva (Myto) 258/68 - Schröder (Myto) 258/68 - Barbirolli (Legato) 258/68 - Gui (Bongiovanni) 258/68 - Questa (Cetra) 258/68 - Solti (Myto) 258/68 - Mehta (GOP) 258/69 - Capuana (GDS) 258/69 - Previtali (Bongiovanni) 258/69 - Previtali -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 47,1927

{H BOSTON SYMPHONY f ORCHESTRA INC. FORTY-SEVENTH SEASON «^| J927-J928 PRoGRTWIE (MONDAY) 5? R^ Cfjanbler & Co. BOSTON COMMON TREMONT ST., AT WEST Exclusive Agents in Boston for JTIFFANYFAVRILE# Glass and Metal Products The Gift of Taste and Distinction THE beauty and artistry of Tiffany Favrile glass and metal products has been ac- knowledged by artists, connoisseurs and collectors the world over. Its rare and delicate coloring alone is sufficient to set it apart from any other type of decorative art work. Only at Chandler & Co., in Boston, will you find this ware, collections of which are exhibited in famous museums both here and abroad. Vases 5.00J to 75.00 Comports 5.001040.00 Bowls 2.50 to 35.00 Fruit Dishes 4.00 Bon Bons 1.50105.00 Baskets 10.00 to 45.00 Candlesticks 7.50 to 25.00 Lamps and Shades 25.00 to 210.00 Plates 7.00 Book Endsf 14.00 to ^o.oo!l!L Frames 18.00 to 30.00 Ash and Card Trays 3.50 to 15.00 Desk Sets 110.00 to 15.00 Be sure that each piece bears the above trade mark or is signed in one of the following ways: • L. C. T. j L. C. TIFFANY LOUIS C. TIFFANY L. C. TIFFANY FAVRILE m LOUIS C. TIFFANY FAVRILE fcym LOUIS C. TIFFANY FURNACES, INC. &&£*&>& SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephones, Ticket and Administration Offices. Back Bay 1492 Boston Symphony Orchestra INC SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor FORTY-SEVENTH SEASON. 1927-1928 Programme MONDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 12, at 8.15 WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1927, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. -

Loving Theseus : the Spectacle of Feminine Passions on the Munich Stage (1662)

Loving Theseus : the spectacle of feminine passions on the Munich stage (1662) Autor(en): Heller, Wendy Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis : eine Veröffentlichung der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Lehr- und Forschungsinstitut für Alte Musik an der Musik-Akademie der Stadt Basel Band (Jahr): 33 (2009) PDF erstellt am: 06.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-868895 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich -

Naples and the Emergence of the Tenor As Hero in Italian Serious Opera

NAPLES AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE TENOR AS HERO IN ITALIAN SERIOUS OPERA Dave William Ekstrum, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 201 8 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor Peter Mondelli, Committee Member Stephen Morscheck, Committee Member Molly Fillmore, Interim Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies of the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Ekstrum, Dave William. Naples and the Emergence of the Tenor as Hero in Italian Serious Opera. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 72 pp., 1 table, bibliography, 159 titles. The dwindling supply of castrati created a crisis in the opera world in the early 19th century. Castrati had dominated opera seria throughout the 18th century, but by the early 1800s their numbers were in decline. Impresarios and composers explored two voice types as substitutes for the castrato in male leading roles in serious operas: the contralto and the tenor. The study includes data from 242 serious operas that premiered in Italy between 1800 and 1840, noting the casting of the male leading role for each opera. At least 67 roles were created for contraltos as male heroes between 1800 and 1834. More roles were created for tenors in that period (at least 105), but until 1825 there is no clear preference for tenors over contraltos except in Naples. The Neapolitan preference for tenors is most likely due to the influence of Bourbon Kings who sought to bring Enlightenment values to Naples. -

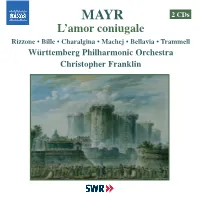

Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 12

660198-99 bk Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 12 2 CDs Also available: MAYR L’amor coniugale Rizzone • Bille • Charalgina • Machej • Bellavia • Trammell Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Christopher Franklin 8.660203-04 8.660220-21 8.660198-99 12 660198-99 bk Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 2 Simon MAYR (1763-1845) Also available: L’amor coniugale (1805) Farsa sentimentale in one act Libretto by Gaetano Rossi (1774-1855) after Jean Nicolas Bouilly Zeliska/Malvino . Cinzia Rizzone, Soprano Amorveno . Francescantonio Bille, Tenor Floreska . Tatjana Charalgina, Soprano Peters . Dariusz Machej, Bass Moroski . Giovanni Bellavia, Bass-baritone Ardelao . Bradley Trammell, Tenor Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Christopher Franklin 8.660037-38 Assistant: Marco Bellei Edition by Florian Bauer for performance at the ROSSINI IN WILDBAD festival, after the revised score of Arrigo Gazzaniga 8.660183-84 8.660198-99 211 8.660198-99 660198-99 bk Mayr US 20/1/08 13:58 Page 10 Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Reutlingen CD 1 43:49 CD 2 39:08 The Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra Reutlingen was established in 1 Sinfonia 7:42 1 Scena: Qual notte eterna (Amorveno) 5:35 1945, developing into one of the leading orchestras in South Germany. It has worked under the direction of, among others, Samuel Friedman, Salvador 2 Gira gira non ti stare attortigliar 2 Aria: Cara immagine adorata (Amorveno) 4:09 Mas Conde and Roberto Paternostro and, since September 2001, Norichika (Floreska, Peters) 4:29 Iimori, who led a highly successful concert tour to Japan in 2006. In addition 3 Animo... ma... cos’hai paura? (Peters, Zeliska) 1:33 to concert series in Reutlingen the orchestra broadcasts regularly with 3 Südwestrundfunk and appears in various cities of South Germany, with tours Sono qua (Zeliska, Peters, Floreska) 4:33 to Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Spain and The Netherlands, often with very 4 Romanza: Una moglie sventurata distinguished soloists.