The Electricity of Every Living Thing V3.Indd Ii 30/01/2018 10:22 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortimers in the 16Th Century Devon Tax Rolls in 1524, Henry VIII Raised

Mortimers in the 16th century Devon Tax Rolls In 1524, Henry VIII raised a tax in attempt to fund the war with France. This was repeated again in 1543. These records are among the earliest accessible records of Mortimers in Devon and give us a glimpse of the prosperity and distribution of members of the Mortimer family during the first half of the 16th century. Overall, there were 25 men and women listed in 1524, having already spread to 16 parishes. 19 years later, they had absented from several of the aforementioned parishes but expanded to 19 parishes. The name has been standardised to Mortimer for internet search purposes. Little meaning was attached to the spellings of names in the 1500s and spelling varied widely. Mortimers in the 1524 Devon Tax Roll Amount Additional Name Parish Hundred Type Notes (£) info Thomas Berry Pomeroy Haytor 2 Goods Mortimer Richard Bradninch Hayridge 6 Goods Mortimer John Bradninch Hayridge 7 Goods Mortimer John Colebrooke Crediton 7 Goods Mortimer Richard Drewsteignton Wonford 4 Goods Mortimer Thomas East Portlemouth Coleridge 1 Goods Mortimer presumably father John Newton St Cyres Crediton 3 Goods of John of Newton Mortimer St C, fl. 1543 William Nymet Tracey North 4 Goods Mortimer (Bow) Tawton Richard West Poughill 3 Goods Mortimer Budleigh John Rewe Wonford 18 Goods Mortimer William (Sandford) Crediton 6 Goods Mortimer Joan (Sandford) Crediton 5 Goods widow Mortimer Roger (Sandford) Crediton 1 Wages Mortimer Nicholas (Sandford) Crediton 4 Goods Mortimer James (Sandford) Crediton 20 Goods Mortimer -

Generic Prescription Assistance NHS Service Which Also Sorts Your Pills and Tells You When to Take Them Gener

Service Contact Details What Support? NHS service which also sorts your pills and tells Generic prescription assistance www.pilltime.co.uk you when to take them Repeat prescriptions from doctor – as works www.lloydspharmacy.com>info> currently, prescriptions passed to your choice of Generic prescription assistance nhs.repeat.prescriptions pharmacy, and if you are not set up for home delivery you need to arrange with pharmacy. British Gas 0333 202 9802, EDF Call 0333 200 5100, E.on 0345 Energy suppliers 052 0000, Npower 0800 073 3000, Scottish Power 0800 027 0072 a web resource listing producers and suppliers in the South Devon area along with their contact details and distribution options. We are currently Shop south Devon www.shopsouthdevon.com working on a download for people to print out and distribute to those without computer access which will be available via the website. https://www.goodsamapp.org/N NHS Volunteer support HS Parish/Community Group Contact Details What Support ? Local Food delivery services: ALANS APPLE - 01548 852 308 GALLEY GIRLS - 07749 636 607 Across Salcombe, Malborough, AUNE VALLEY - 01548 550413 Kingsbridge areas COTTAGE HOTEL - 01548 561 555 SALCOMBE MEAT COMPANY - 01548 843 807 KINGSBRIDGE AGE CONCERN - 01548 856 650 Ashprington & Tuckenhay [email protected] support our local elderly and vulnerable Community Support Group m neighbours Establish a hub that will support those most Email: vulnerable in our area. Those with needs related [email protected] to the coronavirus outbreak should -

Report To: South Hams Executive Date: 14 March 2019 Title: Public Toilet Project Portfolio Area: Environment Services Wards Affe

Report to: South Hams Executive Date: 14 March 2019 Title: Public Toilet Project Portfolio Area: Environment Services Wards Affected: All Relevant Scrutiny Committee: Urgent Decision: N Approval and Y clearance obtained: Date next steps can be taken: Author: Cathy Aubertin Role: Head of Environment Services Practice Contact: [email protected] Recommendations: It is recommended that the Executive resolves to: 1. Approve the installation of Pay on Entry (PoE) equipment at Fore Street public toilets, Kingsbridge. 2. Approve the installation of PoE equipment at the three public toilets in Totnes (Civic Hall, Coronation Road and Steamer Quay) unless an alternative funding solution is offered by the Town Council by 28 February 2019 (verbal update to be given). It is further recommended that the decision on any alternative funding solution offered by the Town Council is assessed for financial and operational viability by the Head of Environment Services Practice in conjunction with the Leader and Portfolio Holder in order to ensure it provides adequate compensation for any income not generated through PoE. 3. Approve the proposed approach of Salcombe Town Council working in partnership with the Salcombe Harbour Board to take over the management and running of the Salcombe Estuary Toilets for a 2 year trial period. This proposal requires a transfer of the 2019/20 service budget to facilitate the pilot and, in the first year, includes a £9,000 contribution towards the roof repairs costs at Mill Bay. It is further recommended that the decision on whether any alternative funding solution offered by the Town Council is financially and operationally viable is taken by the Head of Environment Services Practice in conjunction with the Leader and Portfolio Holder. -

Chivelstone Church

Chivelstone Church KEU3A LHG meeting 18 September 2013 Introduction Dedicated to St Sylvester, a Pope 312-325, though the earliest record of the dedication was as late as 1742. This is a sister church to St Martins of Sherford and both founded by Stokenham Church soon after it was built, (1431). This latter was first dedicated to St Humbert, then St Barnabus and is now St Michael and all Angels. Unlike St Martins of Sherford, Chivelstone church remained a dependency of Stokenham, and through it, associated with the Priory of Totnes, and through the web of ecclesiastical feudal connections, with St Serge of Angers, Tywardeath in Cornwall and ultimately in 1495 with Bisham Abbey in Berkshire…. Chivelstone Church and Parish are a part of the Coleridge Hundred and as such was part of the original bequest to Judel by William the Conqueror. The Coleridge Hundred was composed of 20 parishes including Totnes and the outlying parishes of Ashprington and Thurlestone. (Despite what J. Goodman wrote in his book on Sherford it seems that the Hundreds of Coleridge and Chillington are the same. Heather Burwin in her book "the Coleridge Hundred and its Medieval Court" says that the Hundred Court was at Stokenham). The Stanborough Hundred covered other adjacent Parishes. It is recorded that Sir R.L Newman was the Lord of the Manor at Stokenham and there are memorials to him in the Chivelstone Church. The history of these three churches differs. St Martins (dedicated in1457), was involved in a gift by Gytha, daughter of King Canute, to St Olaves' in Exeter and from then, as St Olaves came under the aegis of William's newly established St Nicholas's Priory, it became one of the possessions of Battle Abbey (also built by William the Conqueror). -

Goodshelter Cleave, East Portlemouth Salcombe, TQ8 8PA

stags.co.uk Residential Lettings Goodshelter Cleave, East Portlemouth Salcombe, TQ8 8PA The ground floor of a chalet bungalow in a beautiful rural setting. • Stunning views • Boating opportunities • Fully furnished • 3 bedrooms • Sitting room • Kitchen & utility room • Bathroom and en-suite • Tenant fees apply • £1,200 per calendar month 01803 866130 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London Goodshelter Cleave, East Portlemouth, Salcombe, TQ8 8PA ACCOMMODATION BEDROOM 3 The ground floor of a chalet bungalow in a beautiful rural Single room with built in wardrobe. Radiator. setting. Hall, sitting room, kitchen/diner, utility room, 1 FAMILY BATHROOM double, 1 twin, 1 single bedroom, family bathroom and en- suite shower room, views over creek and countryside. Ample Modern suite with shower from attachment over bath. 2 x off street parking. The upper floor is occupied for one short heated towel rails. period by arrangement during the summer. SERVICES ENTRANCE HALL Oil fired central heating. Mains water, private sewerage. Mains Coat hanging area. Radiator. electricity. Council Tax South Hams District Council. Band to be advised. SITTING ROOM OUTSIDE Expansive views over countryside and creek. Open fire. 2 x double radiators. The property is accessed via a five bar wooden gate leading to ample parking. There is a pretty garden area and the grounds KITCHEN/DINER include a woodland walk with views over to the creek. Access Wall and base units, refrigerator, dishwasher, electric cooker, to the foreshore, allowing sailing/boating opportunities, is at ceramic hob, microwave oven. Through to dining area with the bottom of the hill by the ford. -

Devon County Council (Ashburton, Bigbury-On-Sea, East Portlemouth, Kingsbridge, Malborough) (Waiting Restrictions) Amendment Order

Devon County Council (Ashburton, Bigbury-on-Sea, East Portlemouth, Kingsbridge, Malborough) (Waiting Restrictions) Amendment Order Devon County Council propose to make this order under the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 to INTRODUCE No Waiting At Any Time on specified lengths of; North Street (Ashburton), Folly Hill (Bigbury- on-Sea), East Portlemouth Corner To Mill Bay & Cross Lane -to- Village Farm Cross (East Portlemouth), Welle House Gardens & Wallingford Road (Kingsbridge) and Collaton Road (Malborough); INTRODUCE No Waiting Mon-Fri 8am-6pm on specified lengths of Wallingford Road, Kingsbridge; REVOKE No Waiting At Any Time on specified lengths of Wallingford Road, Kingsbridge; REVOKE No Waiting 9am-6pm between 01 Apr and 30 Sep on specified lengths of Folly Hill, Bigbury-on- Sea. The draft order, plans & statement of reasons may be seen during usual office hours at the address below in main reception & Ashburton Library, Bigbury-on-Sea Post Office & Stores, Kingsbridge Library, Malborough Post Office & Salcombe Library. Draft order, order being amended & statement of reasons are at www.devon.gov.uk/traffic-orders from 17th January until 7th February & free internet access is available at DCC (excluding mobile) libraries Objections & other comments specifying the proposal & the grounds on which they are made must be in writing to the address below or via www.devon.gov.uk/traffic-orders to arrive by 7th February 2014. Receipt of submissions may not be acknowledged but those received will be considered. A reply will be sent to objectors if the proposal goes ahead. If you make a submission this will form part of a public record which may be made publicly available 17th January 2014 reference IMR/B10155 County Solicitor, Devon County Council, County Hall, Topsham Road, Exeter EX2 4QD statement of reasons The proposed No Waiting At Any Time restrictions on specified lengths of road within Ashburton, Bigbury On Sea, East Portlemouth, Kingsbridge and Malborough, aim to prevent current practices of obstructive and/or dangerous parking from occurring. -

Plan Now, Go Later: 30 Great Breaks in Devon and Dorset

MENU sunday april 12 2020 AFTER THE LOCKDOWN Plan now, go later: 30 great breaks in Devon and Dorset From vineyard stays to art holidays and rambling escapes, we pick the best West Country trips for when we’re travelling again Durdle Door ALAMY Chris Haslam Friday April 10 2020, 6.00pm, The Times Share Saved 1. Lulworth to yourself The shingle circle of Lulworth Cove and Algarve-like arch at Durdle Door were suering from overtourism long before anyone had heard of Dubrovnik, but if you’re staying at the Limestone you can probably have both to yourself. Slip out just before dawn, follow the lane south for a quarter of a mile, then take the path to the right across the fields just past the farm buildings. It takes you round the back of Hambury Tout to drop you, if you’ve timed it right, on Durdle’s doorstep just as the rising sun backlights the arch. Snap it, swim it and swan back to the Limestone for a full English. Later, follow Main Road south to Lulworth Cove. The day-trippers have mostly gone by 6pm. Details Two nights’ B&B from £240 (limestonehotel.co.uk) 2. Dartmoor art school Janet Brady spent 15 years designing for Burberry before becoming an art teacher. Peter Davies studied fine art, and in 2003 the pair opened the Brambles Art Retreat in a 17th-century cottage between the rivers Lyd and Thrushel, just west of Dartmoor. Oering instruction in everything from charcoal to oils, and providing all equipment, they take you to scenic locations on the moors and along the coast to hone your skills. -

East Portlemouth

East Portlemouth • Description:Below East Portlemouth village there is a pleasant stretch of sandy beach on the east bank of Salcombe Harbour. At low tide the sand stretches south to Mill Bay. Café and toilets are close to the beach. There is a ferry to/from Salcombe • Safety:No details available • Access:Access to the beach from the road is via a short sloping path • Dogs:Dogs allowed all year • Directions:East Portlemouth village is approximately 8 miles from Kingsbridge, which is 20 miles from Plymouth. Take the A379 from Plymouth and follow the A379 into south Devon. About a mile after Aveton Gifford, at the Bantham Cross roundabout turn left to continue on the A379 until the Palegate Cross roundabout. Alternatively approaching from the Totnes direction, take the A381 from Totnes until the Palegate Cross roundabout. At the Palegate Cross roundabout turn onto the B3264 and follow this road to Kingsbridge. Approaching Kingsbridge turn right onto the A379 and follow the A379 through Kingsbridge and out of Kingsbridge to the east. About 2 miles east of Kingsbridge at the village of Frogmore, turn right, signposted to East Portlemouth. Follow this road through South Pool and follow the sign posts to East Portlemouth. Note that on this route there are several parts that are impassable at high tide. There are other roads to East Portlemouth across country • Parking:Some road parking above the beach, also one large field car park a 10 minute walk from the beach. Also a very small car park and some road parking in East Portlemouth village, but note the path down from East Portlemouth village is steep. -

South Hams Green Infrastructure Framework

Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................ 5 2 Objectives and Themes ......................................... 13 3 Green Infrastructure Projects ......................... 39 4 Delivering the Framework ..................................88 NOTE This framework has been written by South Hams District Council Officers, in conjunction with a wide range of organisations, to help guide green infrastructure development across the District. The framework should be viewed as a partnership, rather than a South Hams District Council, document reflecting the fact that many projects will be led by other organisations or partnerships and recognising the need for coordinated, targeted delivery of green infrastructure. The following organisations provided comments on a draft version of the framework: Devon Biodiversity Records Centre, Devon Birdwatching and Preservation Society, Devon County Council, Devon Wildlife Trust, Environment Agency, National Trust, Natural England, RSPB, South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Unit and the Woodland Trust. Ideas for green infrastructure projects were also identified through an online survey open to members of the public. All comments received have been taken into account in this final document. The production of the framework has been funded and supported by the South Devon Green Infrastructure Partnership comprising Natural England, South Hams District Council, Torbay Council, Torbay Coast and Countryside Trust, South Devon Area of Outstanding -

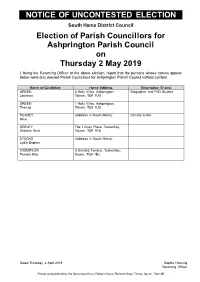

Notice of Uncontested Election Results 2019

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ashprington Parish Council on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ashprington Parish Council without contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) GREEN 8 Holly Villas, Ashprington, Biographer and PhD Student Laurence Totnes, TQ9 7UU GREEN 1 Holly Villas, Ashprington, Thomas Totnes, TQ9 7UU PEAREY (Address in South Hams) Climate Crisis Mike SEELEY Flat 1 Quay Place, Tuckenhay, Sheelah Ruth Totnes, TQ9 7EQ STOCKS (Address in South Hams) Lydia Daphne THOMPSON 9 Orchard Terrace, Tuckenhay, Pamela May Devon, TQ9 7EJ Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Sophie Hosking Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Follaton House, Plymouth Road, Totnes, Devon, TQ9 5NE NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aveton Gifford Parish Council on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aveton Gifford Parish Council without contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BROUSSON 5 Avon Valley Cottages, Aveton Ros Gifford, TQ7 4LE CHERRY 46 Icy Park, Aveton Gifford, Sue Kingsbridge, Devon, TQ7 4LQ DAVIS-BERRY Homefield, Aveton Gifford, TQ7 David Miles 4LF HARCUS Rock Hill House, Fore Street, Sarah Jane Aveton Gifford, -

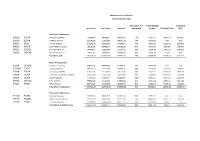

CF REPORT October 2020

2020 Common Fund Receipts as at 31st October 2020 Received as % of CF shortfall 2020 CF shortfall Assesment Due to date Received due to date to date CF shortfall 2019 2018 Barnstaple Archdeaconry B101A B109A Barnstaple Deanery 463298.00 386081.67 290394.00 75% 95687.67 40067.00 39709.51 B201A B204B Hartland Deanery 263791.00 219319.83 149681.50 68% 69638.33 0.00 0.00 B301A B310 Shirwell Deanery 211503.00 176252.50 127448.65 72% 48803.85 21536.00 22594.50 B401A B403K South Molton Deanery 189191.00 157659.17 134186.25 85% 23472.92 9177.00 2484.00 B501A B509CA Torrington Deanery 147098.00 122581.67 101153.30 83% 21428.37 10481.00 19606.10 B601A B605BB Holsworthy Deanery 77121.00 64267.50 41765.76 65% 22501.74 -15.00 0.00 Total Barnstaple 1352002.00 1126162.33 844629.46 75% 281532.87 81246.00 84394.11 Exeter Archdeaconary E101A E109AA Aylesbeare Deanery 534061.00 445050.83 412386.95 93% 32663.88 0.01 2.00 E201AA E207C Cadbury Deanery 253322.00 211101.67 178564.40 85% 32537.27 1213.00 4625.00 E301A E313A Christianity Deanery 870166.00 725138.33 634767.80 88% 90370.53 68512.00 38787.00 E801A E833A Tiverton & Cullompton Deanery 666151.00 555125.83 530116.80 95% 25009.03 84870.82 75594.00 E501A E509D Honiton Deanery 574313.00 478594.17 385680.80 81% 92912.53 33167.00 12016.00 E601A E607GA Kenn Deanery 380812.00 317343.33 274980.31 87% 42363.02 23842.45 20157.84 E701A E706A Ottery Deanery 685714.00 571428.33 550046.50 96% 21381.83 17783.00 11488.00 Total Exeter Archdeaconry 3964539.00 3303782.50 2966543.56 90% 337238.11 229388.28 162669.84 Plymouth -

2 West Waterhead 2 West Waterhead East Portlemouth, Salcombe, TQ8 8PA Salcombe 8 Miles Dartmouth 11 Miles

2 West Waterhead 2 West Waterhead East Portlemouth, Salcombe, TQ8 8PA Salcombe 8 miles Dartmouth 11 miles • Beautiful rural outlook • Close to the estuary • 19' dual aspect living room • 29' conservatory • Kitchen • Three ensuite double bedrooms • Good sized gardens • Available with vacant possession Guide price £365,000 SITUATION AND DESCRIPTION The property lies almost equi-distant two of the most favoured and sought- after villages in the South Hams. Nestled in the beautiful Holset Valley, South Pool sits within an area of outstanding national beauty (AONB) and conservation. This pretty village has a 14th century church, an award-winning pub, The Millbrook Inn and a thriving local community. It lies at the head of a long, beautiful creek off the Salcombe estuary and offers extensive walking and bird watching opportunities. East Portlemouth is a favoured village with a beautiful old parish church. A A spacious single storey dwelling of character with tranquil rural foot ferry connects the village to Salcombe on the opposite side of the estuary where you will find a bustling town with shops, pubs and restaurants. Renowned for it's sailing and boating facilities, Salcombe is located beside views and just 300 yards or so from a beautiful creek. one of the most beautiful estuaries in the South West, with miles of sheltered water and fine sandy beaches on either side towards its mouth. School bus services run from East Portlemouth to Kingsbridge. We understand that the original building was run as an hotel until the late 1980s when it was converted into three single storey residential dwellings.