Promoting Green Infrastructure in Mexico's Northern Border The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Trends and Sources of TSP in a Sonoran Desert City: Can the North America Monsoon Enhance Dust Emissions?

Atmospheric Environment 110 (2015) 111e121 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Atmospheric Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv Historical trends and sources of TSP in a Sonoran desert city: Can the North America Monsoon enhance dust emissions? Veronica Moreno-Rodríguez a, Rafael Del Rio-Salas b, David K. Adams c, Lucas Ochoa-Landin d, Joel Zepeda e, Agustín Gomez-Alvarez f, Juan Palafox-Reyes d, * Diana Meza-Figueroa d, a Posgrado en Ciencias de la Tierra, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico b Instituto de Geología, Estacion Regional del Noroeste, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Colosio y Madrid s/n, 83240 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico c Centro de Ciencias de la Atmosfera, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico d Departamento de Geología, Division de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Sonora, Rosales y Encinas, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico e Instituto Municipal de Ecología, Desarrollo Urbano y Ecología, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico f Departamento de Ingeniería Química y Metalurgia, Universidad de Sonora, Rosales y Encinas, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico highlights Historical TSP trends in a Sonoran desert city. Monsoon behavior enhances dust emission in urban area. Cement and traffic sources affect geogenic dust. Lack of storm drainage system promoting dust resuspension. article info abstract Article history: In this work, the trends of total suspended particulate matter (TSP) were analyzed during a period of 12 Received 26 December 2014 years (2000e2012) on the basis of meteorological parameters. The results of historical trends of TSP Received in revised form show that post-monsoon dust emission seems to be connected to rainfall distribution in the urban 21 March 2015 environment. -

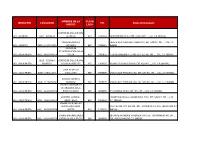

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

Ayuntamiento De Hermosillo - Cities 2019

Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo - Cities 2019 Introduction (0.1) Please give a general description and introduction to your city including your city’s reporting boundary in the table below. Administrative Description of city boundary City Metropolitan Hermosillo is the capital of the Sonora State in Mexico, and a regional example in the development of farming, animal husbandry and boundary area manufacturing industries. Hermosillo is advantaged with extraordinarily extensive municipal boundaries; its metropolitan area has an extension of 1,273 km² and 727,267 inhabitants (INEGI, 2010). Located on coordinates 29°05’56”N 110°57’15”W, Hermosillo’s climate is desert-arid (Köppen-Geiger classification). It has an average rainfall of 328 mm per year and an average annual maximum temperature of 34.0 degrees Celsius. Mexico’s National Atlas of Zones with High Clean Energy Potential, distinguishes Hermosillo as place of high solar energy yield, with a potential of 6,000-6,249 Wh/m²/day. Hermosillo is a strategic place in Mexico’s business network. Situated about 280 kilometers from the United States border (south of Arizona), Hermosillo is a key member of the Arizona-Sonora mega region and a link of the CANAMEX corridor which connects Canada, Mexico and the United States. The city is among the “top 5 best cities to live in Mexico”, as declared by the Strategic Communication Office (IMCO, 2018). Hermosillo’s cultural heritage, cleanliness, low cost of living, recreational amenities and skilled workforce are core characteristics that make it a stunning place to live and work. In terms of governance, Hermosillo’s status as the capital of Sonora gives it a lot of institutional and political advantages, particularly in terms of access to investment programs and resources, as well as power structures that matter in urban decision-making. -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

City of Nogales General Plan

City of Nogales General Plan Background and Current Conditions Volume City of Nogales General Plan Background and Current Conditions Volume City of Nogales General Plan Parks Open Sports Space Industry History Culture Prepared for: Prepared by: City of Nogales The Planning Center 1450 North Hohokam Drive 2 East Congress, Suite 600 Nogales, Arizona Tucson, Arizona Background and Current Conditions Volume City of Nogales General Plan Update Table of Contents Table of Contents i Acknowledgements ii Introduction and Overview 1 History and Background 12 Economic Development Framework 20 Background Analysis and Inventory 35 Nogales Demographics Profile 69 Housing and Household Characteristics 71 Parks, Recreation, Trails and OpenSpace 78 Technical Report Conclusions 84 Bibliography and References 86 Exhibits Exhibit 1: International and Regional Context 7 Exhibit 2: Local Context 8 Exhibit 3: Nogales Designated Growth Area 9 Exhibit 4: History of Annexation 19 Exhibit 5: Physical Setting 39 Exhibit 6: Existing Rivers and Washes 40 Exhibit 7: Topography 41 Exhibit 8: Vegetative Communities 42 Exhibit 9: Functionally Classified Roads 54 Exhibit 10: School Districts and Schools 62 Background and Current Conditions Volume Table of Contents Page i City of Nogales General Plan City of Nogales Department Directors Alejandro Barcenas, Public Works Director Danitza Lopez, Library Director Micah Gaudet, Housing Director Jeffery Sargent, Fire Chief Juan Guerra, City Engineer John E. Kissinger, Deputy City Manager Leticia Robinson, City Clerk Marcel Bachelier -

Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan 2017-2021

Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan 2017-2021 PROJECTS FOR BUILDING THE ENVIRONMENT AND THE ECONOMY IN THE ARIZONA-SONORA BORDER REGION 2 ARIZONA-SONORA ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures Letter from Agency Directors 06 Executive Summary 08 Environmental Context of the Arizona-Sonora Region 10 Strategic Plans of Arizona and Sonora Agencies and Potential Synergies 12 The Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan Process 13 Implementing the Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan 15 Economic Competitiveness and the Environment in the Arizona-Sonora Border Region 21 Strategic Environmental Projects 2017-2021 21 Overview of Strategic Arizona-Sonora Environmental Projects 22 Water Projects 26 Air Projects 29 Waste Management Projects 32 Wildlife Projects 33 Additional Projects for Future Consideration 33 Water Projects/Prioritization 36 Air Projects/Prioritization 37 Waste Management Projects/Prioritization 38 Wildlife Projects/Prioritization ARIZONA-SONORA ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2021 5 LETTER FROM AGENCY DIRECTORS LIST OF FIGURES 08 Figure 1: The U.S.-Mexico Border Zone 09 Figure 2: Border environmental concerns identified by CEDES/ADEQ Dear Colleagues, Friends and Neighbors, 10 Figure 4: CEDES Strategic Areas Overview, 2016-2021 We present to you this first Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan for 2017-2021. In June 2016, the Environment and Water Committee of the Arizona-Mexico Commission/Comisión So- Figure 5: ADEQ Strategic Plan Overview 11 nora-Arizona agreed to produce this plan in order to enhance synergies and maximize the effec- tive use of resources. This plan is the latest effort in a long history of cross-border collaboration 12 Figure 6: Overview of Strategic Plan Development Process, 2016 involving bilateral, federal, state and local agencies, as well as the private sector and non-gov- ernmental organizations in Arizona and Sonora. -

Lunes 13 De Mayo De 2019. CCIII Número 38 Secc. I

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • Conven io Autorización Número 10-781 -2014 CONVENIO AUTORIZACIÓN No. 10-781 -2014 QUE MODIFICA i._AS CLAUSULAS TERCERA Y DECIMA SEXTA DEL CONVENIO AUTORIZAC/ON No. 10-498-2002, PARA LA EJECUCIÓN DE LAS OBRAS DE URBANIZACIÓN DEL FRACCIONAMIENTO "GALA 11 ", DE LA CIUDAD DE HERMOSILLO, SONORA, MUNICIPI O DEL MISMO NOMBRE, QUE OTORGA EL H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE HERMOSILLO POR CONDUCTO DE LA COORDINACIÓN GENERAL DE INFRAESTRUCTURA, DESARROLLO URBANO Y ECOLOGÍA, A LA EMPRESA "CONSTRUVISIÓN, S.A. DE C.V.". La Coordinación General de Infraestructura, Desarrollo Urbano y Ecología, del H. Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo, a través de su Coordinador General, el C, MARCOS NORIEGA MUÑOZ, con fundamento en los artículos 1, 5 fracción 111 , 9 fracción X y 102 fracción V, de la Ley de Ordenamiento Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano del Estado de Sonora; 61 fracción I inciso C, 81 , 82, 84 y 85 de la Ley de Gobierno y Administración Municipal; y 1, 16 Bis, 16 Bis 2, 17, 32 y '.i3 íracción V y último párrafo del Reglamento Interior de la Administración Pública Municipal Directa del H. Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo; otorga la presente AUTORIZACIÓN al tenor de los siguientes términos y condiciones : TÉRMINOS 1, EL C. ING. JAIME ISAAC FELIX GANDARA, representante legal y apoderado general para pleitos y cobranzas, actos de administración y dominio, de la empresa "CONSTRUVISIÓN, S.A. o u raE DE C.V.", con base en lo dispuesto en los artículos 94, 95 y 99 de la Ley de Ordenamiento ·;::Q) ~:e Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano del Estado de Sonora, con fecha 29 de Septiembre del 2014, OJO t;"' solicitó la autorización para modificar el fraccionamiento habitacional de clasificación unifamiliar, OJO) U,"C denominado "GALA 11" , ubicado al Sur de la Ciudad de Hermosillo, Sonora. -

Binational Prevention and Emergency Response Plan Between Cochise County, Arizona and Naco, Sonora

Binational Prevention and Emergency Response Plan Between Cochise County, Arizona and Naco, Sonora BINATIONAL PREVENTION AND EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN BETWEEN NACO, SONORA AND COCHISE COUNTY, ARIZONA October 4, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. v FORWARD................................................................................................................................... vii MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING................................................................................. 1 EMERGENCY NOTIFICATION FORM ...................................................................................... 7 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Naco, Sonora/Cochise County, Arizona Plan Area ...............................................10 1.1.1 Physical Environment ................................................................................10 1.1.2 Population ..................................................................................................11 1.1.3 Economy ....................................................................................................12 1.1.4 Infrastructure..............................................................................................12 1.1.5 Cultural Significance .................................................................................13 1.2 Authority................................................................................................................13 -

01 049 Ieesonora 02 049 Hermosillo 03 001 Aconchi 04 002 Agua Prieta 05 062 Álamos 06 003 Altar 07 004 Arivechi 08 005 Arizpe 0

SEDES PARA INTEGRACION DE EXPEDIENTES ASPIRANTES A CONSEJEROS ELECTORALES SEDES CLAVE MPIO MUNICIPIO DIRECCIÓN BIBLIOTECA Luis Donaldo Colosio #35 Col. Centro. Hermosillo, IEESONORA 01 049 Sonora C. GUERRERO ENTRE GASTÓN MADRID Y EVERARDO 02 049 HERMOSILLO MONROY, COL. CENTRO C. INDEPENDENCIA ENTRE PESQUEIRA Y JESUS GARCÍA , COL. 03 001 ACONCHI CENTRO 04 002 AGUA PRIETA AVENIDA CUATRO ESQ. SEIS # 640, COL. SECTOR INDUSTRIAL COMERCIO # 6, ENTR GUTIERREZ Y GUADALUPE VICTORIA, 05 062 ÁLAMOS COL. CENTRO C. MORELOS S/N, ENTRE OCAMPO Y FCO. I MADERO JUNTO 06 003 ALTAR AL ESTADIO DE BEIS, COL. DE ABAJO CUAUHTEMOC NO 8, ENTRE VICENTE GUERRERO Y MORELOS, 07 004 ARIVECHI COL. DETRÁS DE PALACIO 08 005 ARIZPE DIODORO CORELLA Y PEDRO GARCÍA CONDE, COL. CENTRO CALLE OBREGÓN, ENTRE DOLORES MUÑOZ Y REVOLUCIÓN, 09 006 ATÍL COL. CENTRO 10 007 BACADÉHUACHI SUFRAGIO EFECTIVO S/N CALLE ZARAGOZA S/N, ENTRE 16 DE SEPTIEMBRE Y CIEN 11 008 BACANORA FUEGOS CALLE 5 DE MAYO, ENTRE OBREGÓN Y LIBERTAD, COL. 12 009 BACERAC CENTRO, FRENTE A LA PLAZA PÚBLICA AVENIDA FRANCISCO I. MADERO, ENTRE PABLO SIDAR Y 13 010 BACOACHI GALLEGO, COL. 5 DE MAYO 14 058 BÁCUM BELISARIO DOMINGUEZ ESQ. RODOLFO FELIX, COL. CENTRO CALLE LIBERTAD ENTRE OBREGÓN Y CONSTITUCIÓN, COL. 15 011 BANAMICHI CENTRO FLORENCIO RUÍZ (INSTALACIONES DEL DIF MUNICIPAL), COL. 16 012 BAVIÁCORA CENTRO CALLE OCAMPO S/N, ENTRE CALLE SUY Y OAXACA, COL. 17 013 BAVISPE CENTRO. 18 071 BENITO JUÁREZ INDEPENDENCIA Y CIRCUNVALACIÓN FINAL, COL. CENTRO JUAREZ NORTE, ENTRE Y SAN FERNANDO PONIENTE Y TERÁN 19 014 BENJAMIN HILL PONIENTE, COL. -

PUNTOS RESOLUTIVOS DE LAS SENTENCIAS DICTADAS POR LOS TRIBUNALES AGRARIOS Dictada El 8 De Julio De 1996

Lunes 2 de diciembre de 1996 BOLETIN JUDICIAL AGRARIO 3 PUNTOS RESOLUTIVOS DE LAS SENTENCIAS DICTADAS POR LOS TRIBUNALES AGRARIOS Dictada el 8 de julio de 1996 JUICIO AGRARIO: 449/T.U.A.-28/95 Pob.: “VILLA HIDALGO” Mpio.: Villa Hidalgo Dictada el 8 de julio de 1996 Edo.: Sonora Acc.: Reconocimiento de derechos Pob.: “VILLA HIDALGO” agrarios. Mpio.: Villa Hidalgo Edo.: Sonora PRIMERO. Es improcedente el Acc.: Reconocimiento de derechos reconocimiento de derechos agrarios solicitado agrarios. por JOSÉ DURAZO VELÁZQUEZ, derivado de la aceptación de la Asamblea General de PRIMERO. Es improcedente el Ejidatarios celebrada el catorce de junio de mil reconocimiento de derechos agrarios solicitado novecientos noventa y cuatro, en el Poblado por IGNACIO MORENO LEYVA, derivado "VILLA HIDALGO", Municipio de Villa de la aceptación de la Asamblea General de Hidalgo, Sonora, conforme a lo razonado en el Ejidatarios celebrada el catorce de junio de mil último considerando de esta resolución. novecientos noventa y cuatro, en el Poblado SEGUNDO. Se deja a salvo los derechos "VILLA HIDALGO", Municipio de Villa del C. JOSÉ DURAZO VELÁZQUEZ, para Hidalgo, Sonora, conforme a lo razonado en el que en su oportunidad pueda volver a ejercitar último Considerando de esta resolución. la acción pretendida en el presente asunto. SEGUNDO. Se deja a salvo los derechos TERCERO. Notifíquese personalmente al del C. IGNACIO MORENO LEYVA, para interesado, y publíquense los puntos que en su oportunidad pueda volver a ejercitar resolutivos de esta fallo en el Boletín Judicial la acción pretendida en el presente asunto. Agrario y en los estrados de este Tribunal. En TERCERO. -

Evaluation of Small Scale Burning in Nogales, Sonora

EVALUATION OF SMALL SCALE BURNING OF WASTE AND WOOD IN NOGALES, SONORA Final Report Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona November 2007 (updated April 2008) Cover Photo: Urban Rocket Elbow Stove created from the shell of a discarded washing machine EVALUATION OF SMALL SCALE BURNING OF WASTE AND WOOD IN NOGALES, SONORA Final Report Prepared for: José Rodriguez Edna Mendoza Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Tucson, Arizona Prepared by: Diane Austin Gigi Owen Sara Curtin Mosher Megan Sheehan Jeremy Slack Olga Cuellar Maya Abela Paola Molina Brian Burke Ben McMahan Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona November 2007 (updated April 2008) Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... vii Chapter One: Background of Study ........................................................................................... 1 Goals and Objectives of the Study .......................................................................................... -

De La Coordinación Estatal De Protección Civil De Sonora

DE LA COORDINACIÓN ESTATAL DE PROTECCIÓN CIVIL DE SONORA, MEDIANTE LA CUAL REMITE CONTESTACIÓN A PUNTO DE ACUERDO, APROBADO POR LA CÁMARA DE DIPUTADOS, PARA ATENDER A LOS DAMNIFICADOS POR LAS INTENSAS LLUVIAS OCURRIDAS EN ESE ESTADO, SINALOA Y MICHOACÁN Hermosillo, Sonora, a 1 de noviembre de 2018. Diputada María de los Dolores Padierna Luna Vicepresidenta de la Mesa Directiva Cámara de Diputados Poder Legislativo Federal Presente En seguimiento al oficio número DGPL-64-II-8-0096, dirigido a la ciudadana licenciada Claudia Artemiza Pavlovich Arellano, gobernadora constitucional del estado de Sonora, mediante el cual informa sobre la sesión de la Mesa Directiva celebrada el 25 de septiembre pasado, donde se aprobó el acuerdo de la Junta de Coordinación Política por el que se exhorta a diversas autoridades a realizar urgentemente las acciones necesarias para dar atención a los damnificados por las intensas lluvias ocurridas en los estados de Sinaloa, Sonora y Michoacán y se logre el pronto restablecimiento de las condiciones de normalidad en dichas entidades federativas, al respecto le informo: - Cronología de acciones por declaratorias de emergencia y desastre, septiembre-octubre de 2018 Depresión tropical 19-E declaratoria de emergencia • 20 de septiembre, la ciudadana gobernadora del estado envía la solicitud de declaratoria de emergencia a la Coordinación Nacional de Protección Civil (CNPC) de la Secretaría de Gobernación, que contiene 13 municipios del estado de Sonora (Álamos, Bácum, Benito Juárez, Cajeme, Empalme, Etchojoa, Guaymas, Hermosillo, Huatabampo, Navojoa, Ouiriego, Rosario y San Ignacio Rio Muerto) por la presencia de la depresión tropical 19-E del 18 al 20 de septiembre de 2018.