Evaluation of Small Scale Burning in Nogales, Sonora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Trends and Sources of TSP in a Sonoran Desert City: Can the North America Monsoon Enhance Dust Emissions?

Atmospheric Environment 110 (2015) 111e121 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Atmospheric Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv Historical trends and sources of TSP in a Sonoran desert city: Can the North America Monsoon enhance dust emissions? Veronica Moreno-Rodríguez a, Rafael Del Rio-Salas b, David K. Adams c, Lucas Ochoa-Landin d, Joel Zepeda e, Agustín Gomez-Alvarez f, Juan Palafox-Reyes d, * Diana Meza-Figueroa d, a Posgrado en Ciencias de la Tierra, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico b Instituto de Geología, Estacion Regional del Noroeste, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Colosio y Madrid s/n, 83240 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico c Centro de Ciencias de la Atmosfera, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico d Departamento de Geología, Division de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Sonora, Rosales y Encinas, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico e Instituto Municipal de Ecología, Desarrollo Urbano y Ecología, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico f Departamento de Ingeniería Química y Metalurgia, Universidad de Sonora, Rosales y Encinas, 83000 Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico highlights Historical TSP trends in a Sonoran desert city. Monsoon behavior enhances dust emission in urban area. Cement and traffic sources affect geogenic dust. Lack of storm drainage system promoting dust resuspension. article info abstract Article history: In this work, the trends of total suspended particulate matter (TSP) were analyzed during a period of 12 Received 26 December 2014 years (2000e2012) on the basis of meteorological parameters. The results of historical trends of TSP Received in revised form show that post-monsoon dust emission seems to be connected to rainfall distribution in the urban 21 March 2015 environment. -

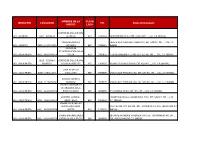

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

Ayuntamiento De Hermosillo - Cities 2019

Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo - Cities 2019 Introduction (0.1) Please give a general description and introduction to your city including your city’s reporting boundary in the table below. Administrative Description of city boundary City Metropolitan Hermosillo is the capital of the Sonora State in Mexico, and a regional example in the development of farming, animal husbandry and boundary area manufacturing industries. Hermosillo is advantaged with extraordinarily extensive municipal boundaries; its metropolitan area has an extension of 1,273 km² and 727,267 inhabitants (INEGI, 2010). Located on coordinates 29°05’56”N 110°57’15”W, Hermosillo’s climate is desert-arid (Köppen-Geiger classification). It has an average rainfall of 328 mm per year and an average annual maximum temperature of 34.0 degrees Celsius. Mexico’s National Atlas of Zones with High Clean Energy Potential, distinguishes Hermosillo as place of high solar energy yield, with a potential of 6,000-6,249 Wh/m²/day. Hermosillo is a strategic place in Mexico’s business network. Situated about 280 kilometers from the United States border (south of Arizona), Hermosillo is a key member of the Arizona-Sonora mega region and a link of the CANAMEX corridor which connects Canada, Mexico and the United States. The city is among the “top 5 best cities to live in Mexico”, as declared by the Strategic Communication Office (IMCO, 2018). Hermosillo’s cultural heritage, cleanliness, low cost of living, recreational amenities and skilled workforce are core characteristics that make it a stunning place to live and work. In terms of governance, Hermosillo’s status as the capital of Sonora gives it a lot of institutional and political advantages, particularly in terms of access to investment programs and resources, as well as power structures that matter in urban decision-making. -

A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Sonora, Mexico

52 A. J. van Rossem Occ. Papers Order FALCONIFORMES Birds of PreY Family Cathartidae American Vultures Coragyps atratus (Bechstein) Black Vulture Vultur atratus Bechstein, in Latham, Allgem. Ueb., Vögel, 1, 1793, Anh., 655 (Florida). Coragyps atratus atratus van Rossem, 1931c, 242 (Guaymas; Saric; Pesqueira: Obregon; Tesia); 1934d, 428 (Oposura). — Bent, 1937, 43, in text (Guaymas: Tonichi). — Abbott, 1941, 417 (Guaymas). — Huey, 1942, 363 (boundary at Quito vaquita) . Cathartista atrata Belding, 1883, 344 (Guaymas). — Salvin and Godman, 1901. 133 (Guaymas). Common, locally abundant, resident of Lower Sonoran and Tropical zones almost throughout the State, except that there are no records as yet from the deserts west of longitude 113°, nor from any of the islands. Concentration is most likely to occur in the vicinity of towns and ranches. A rather rapid extension of range to the northward seems to have taken place within a relatively few years for the species was not noted by earlier observers anywhere north of the limits of the Tropical zone (Guaymas and Oposura). It is now common nearly everywhere, a few modern records being Nogales and Rancho La Arizona southward to Agiabampo, with distribution almost continuous and with numbers rapidly increasing southerly, May and June, 1937 (van Rossem notes); Pilares, in the north east, June 23, 1935 (Univ. Mich.); Altar, in the northwest, February 2, 1932 (Phillips notes); Magdalena, May, 1925 (Dawson notes; [not noted in that locality by Evermann and Jenkins in July, 1887]). The highest altitudes where observed to date are Rancho La Arizona, 3200 feet; Nogales, 3850 feet; Rancho Santa Bárbara, 5000 feet, the last at the lower fringe of the Transition zone. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I Sonora, Mexico Municipal Development Project

I fJl-~-5r3 I 5 5 I 9 7 7 I SONORA, MEXICO I MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT: DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT OF I THE CITY OF AGUA PRIETA I September 1996 I I Prepared for I U.S. Agency for International Development I By Frank B. Ohnesorgen I Ramon R. Osuna I Julio Zapata I I INTERNATIONAL CITY/COUNTY MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION Municipal Development and Management USAID Contract No. PCE-I008-Q-00-5002-00 -I USAID Project No. 940-1008 Delivery Order No.5 I I I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 I 2 METHODOLOGY 2 I 3 GENERAL MUNICIPAL CHARACTERISTICS 2 4 DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT AND OBSERVATIONS 2 I 4.1 Office ofthe Mayor (Presidente Municipal) and Councilmembers (Regidores) 2 4.2 The Office ofthe Municipal Secretary (Secretario Municipal) 3 4.3 The Office ofSolidarity Programs (Director de Programas de Solideridad) 4 I 4.4 The Office ofHuman Resources (Personnel) (Director de Recursos Humanos) 4 4.5 The Office ofMunicipal Controller (Contraloria Municipal) 5 4.6 The Office ofPublic Works (Directora de Obras Pilblicas) 6 I 4.7 The Office ofIntegral Family Development (Desarrollo Integral de Familias) 6 4.8 The Office ofPublic Services (Director de Servicios Pilblicos) 7 4.9 The Office ofMunicipal Treasurer (Tesorero Municipal) 7 I 4.10 The Office ofProcurator (Sindico Procurador) 8 I 5 GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC OBSERVATIONS 9 6 RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE MAYOR AND COUNCIL 10 I I I I I I I I I I I -111- ABSTRACT I The Sonora, Mexico Municipal Development Project (SMMD) was initiated in response to the local government demand for autonomy in Mexico. -

Project Proposal

Board Document BD 2007-XX August 29, 2007 Border Environment Cooperation Commission Wastewater Collection Project in Agua Prieta, Sonora. 1. General Criteria 1.a Project Type The project consists of improving and expanding the wastewater collection system for the community of Agua Prieta, in the municipality of Agua Prieta, Sonora. This project belongs to BECC's Wastewater Treatment and Domestic Water and Wastewater Hookups Sectors. 1.b Project Categories The project belongs to the category of Community Environmental Infrastructure Projects – Community-wide Impact. The project will improve wastewater collection quality service in the community of Agua Prieta resulting in a positive impact to this community. 1.c Project Location and Community Profile The State of Sonora is located in the northeastern part of the Republic of Mexico, adjacent to the United States of America. Agua Prieta, Sonora is located in the northeastern part of the State of Sonora and neighbors the City of Douglas, Arizona, USA. About 47% of the population in Agua Prieta is employed in maquilas, commerce or by rendering services. The rest of the population is employed in agricultural related activities. The following figure shows the geographic location of Agua Prieta. 1 Board Document BD 2007-XX BECC Certification Document Agua Prieta, Sonora Demographics Population projections prepared during the development of the Final Design of the Wastewater Collection System1 for Agua Prieta, Sonora were based on census data obtained by the National Institute for Statistics, Geography, and Information (INEGI 2000 for its initial in Spanish) and the National Population Council (CONAPO for its initial in Spanish). The current population (2007) has been estimated to be 70,523 inhabitants and estimations for the year 2027 forecast were 79,143 inhabitants. -

Health Consultation Trans-Border Exposure to Smoke from Refuse

Health Consultation Trans-border Exposure to Smoke From a Refuse Fire in Naco, Sonora, Mexico December 1 to December 5, 2001 Naco, Arizona, USA, and Naco, Sonora, Mexico Prepared by Arizona Department of Health Services Office of Environmental Health Environmental Health Consultation Services under cooperative agreement with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry March 2002 Introduction A refuse dump near Naco, Sonora, Mexico, caught fire and burned from December 1 to December 5, 2001. The fire, which consumed large quantities of household refuse, also generated a large quantity of smoke. During this period, considerable smoke was intermittently present in Naco, Arizona. Persons up to 17 miles away from the fire reported smelling the smoke. At night in the Naco area, smoke concentrations were generally higher when weather conditions caused smoke to settle in residential neighborhoods on both sides of the border. The Arizona Department of Health Services and the Cochise County Health Department issued public health advisories for the evenings of December 1 and 2, 2001. The Naco, Arizona, Port of Entry closed during periods of heavy smoke to protect the health and safety of employees and travelers. The Cochise County Board of Supervisors declared a state of emergency to gain access to state and federal resources. This report summarizes the events that occurred during the fire and analyzes the data collected by the Arizona Department of Health Services and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to determine the extent of the public health threat from the fire. Background Saturday, December 1, 2001 The Cochise County Health Department received calls from citizens complaining about the smoke. -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

City of Nogales General Plan

City of Nogales General Plan Background and Current Conditions Volume City of Nogales General Plan Background and Current Conditions Volume City of Nogales General Plan Parks Open Sports Space Industry History Culture Prepared for: Prepared by: City of Nogales The Planning Center 1450 North Hohokam Drive 2 East Congress, Suite 600 Nogales, Arizona Tucson, Arizona Background and Current Conditions Volume City of Nogales General Plan Update Table of Contents Table of Contents i Acknowledgements ii Introduction and Overview 1 History and Background 12 Economic Development Framework 20 Background Analysis and Inventory 35 Nogales Demographics Profile 69 Housing and Household Characteristics 71 Parks, Recreation, Trails and OpenSpace 78 Technical Report Conclusions 84 Bibliography and References 86 Exhibits Exhibit 1: International and Regional Context 7 Exhibit 2: Local Context 8 Exhibit 3: Nogales Designated Growth Area 9 Exhibit 4: History of Annexation 19 Exhibit 5: Physical Setting 39 Exhibit 6: Existing Rivers and Washes 40 Exhibit 7: Topography 41 Exhibit 8: Vegetative Communities 42 Exhibit 9: Functionally Classified Roads 54 Exhibit 10: School Districts and Schools 62 Background and Current Conditions Volume Table of Contents Page i City of Nogales General Plan City of Nogales Department Directors Alejandro Barcenas, Public Works Director Danitza Lopez, Library Director Micah Gaudet, Housing Director Jeffery Sargent, Fire Chief Juan Guerra, City Engineer John E. Kissinger, Deputy City Manager Leticia Robinson, City Clerk Marcel Bachelier -

Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan 2017-2021

Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan 2017-2021 PROJECTS FOR BUILDING THE ENVIRONMENT AND THE ECONOMY IN THE ARIZONA-SONORA BORDER REGION 2 ARIZONA-SONORA ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures Letter from Agency Directors 06 Executive Summary 08 Environmental Context of the Arizona-Sonora Region 10 Strategic Plans of Arizona and Sonora Agencies and Potential Synergies 12 The Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan Process 13 Implementing the Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan 15 Economic Competitiveness and the Environment in the Arizona-Sonora Border Region 21 Strategic Environmental Projects 2017-2021 21 Overview of Strategic Arizona-Sonora Environmental Projects 22 Water Projects 26 Air Projects 29 Waste Management Projects 32 Wildlife Projects 33 Additional Projects for Future Consideration 33 Water Projects/Prioritization 36 Air Projects/Prioritization 37 Waste Management Projects/Prioritization 38 Wildlife Projects/Prioritization ARIZONA-SONORA ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2021 5 LETTER FROM AGENCY DIRECTORS LIST OF FIGURES 08 Figure 1: The U.S.-Mexico Border Zone 09 Figure 2: Border environmental concerns identified by CEDES/ADEQ Dear Colleagues, Friends and Neighbors, 10 Figure 4: CEDES Strategic Areas Overview, 2016-2021 We present to you this first Arizona-Sonora Environmental Strategic Plan for 2017-2021. In June 2016, the Environment and Water Committee of the Arizona-Mexico Commission/Comisión So- Figure 5: ADEQ Strategic Plan Overview 11 nora-Arizona agreed to produce this plan in order to enhance synergies and maximize the effec- tive use of resources. This plan is the latest effort in a long history of cross-border collaboration 12 Figure 6: Overview of Strategic Plan Development Process, 2016 involving bilateral, federal, state and local agencies, as well as the private sector and non-gov- ernmental organizations in Arizona and Sonora. -

Lunes 13 De Mayo De 2019. CCIII Número 38 Secc. I

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • Conven io Autorización Número 10-781 -2014 CONVENIO AUTORIZACIÓN No. 10-781 -2014 QUE MODIFICA i._AS CLAUSULAS TERCERA Y DECIMA SEXTA DEL CONVENIO AUTORIZAC/ON No. 10-498-2002, PARA LA EJECUCIÓN DE LAS OBRAS DE URBANIZACIÓN DEL FRACCIONAMIENTO "GALA 11 ", DE LA CIUDAD DE HERMOSILLO, SONORA, MUNICIPI O DEL MISMO NOMBRE, QUE OTORGA EL H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE HERMOSILLO POR CONDUCTO DE LA COORDINACIÓN GENERAL DE INFRAESTRUCTURA, DESARROLLO URBANO Y ECOLOGÍA, A LA EMPRESA "CONSTRUVISIÓN, S.A. DE C.V.". La Coordinación General de Infraestructura, Desarrollo Urbano y Ecología, del H. Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo, a través de su Coordinador General, el C, MARCOS NORIEGA MUÑOZ, con fundamento en los artículos 1, 5 fracción 111 , 9 fracción X y 102 fracción V, de la Ley de Ordenamiento Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano del Estado de Sonora; 61 fracción I inciso C, 81 , 82, 84 y 85 de la Ley de Gobierno y Administración Municipal; y 1, 16 Bis, 16 Bis 2, 17, 32 y '.i3 íracción V y último párrafo del Reglamento Interior de la Administración Pública Municipal Directa del H. Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo; otorga la presente AUTORIZACIÓN al tenor de los siguientes términos y condiciones : TÉRMINOS 1, EL C. ING. JAIME ISAAC FELIX GANDARA, representante legal y apoderado general para pleitos y cobranzas, actos de administración y dominio, de la empresa "CONSTRUVISIÓN, S.A. o u raE DE C.V.", con base en lo dispuesto en los artículos 94, 95 y 99 de la Ley de Ordenamiento ·;::Q) ~:e Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano del Estado de Sonora, con fecha 29 de Septiembre del 2014, OJO t;"' solicitó la autorización para modificar el fraccionamiento habitacional de clasificación unifamiliar, OJO) U,"C denominado "GALA 11" , ubicado al Sur de la Ciudad de Hermosillo, Sonora. -

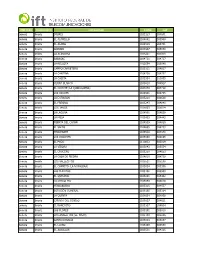

Sonora Imuris IMURIS 1105123 304641 Sonora Imuris EL

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Sonora Imuris IMURIS 1105123 304641 Sonora Imuris EL ALAMILLO 1104042 303908 Sonora Imuris EL ÁLAMO 1104939 304701 Sonora Imuris ARIBABI 1103907 305158 Sonora Imuris LA ATASCOSA 1105221 305853 Sonora Imuris BABASAC 1104721 304727 Sonora Imuris LA BELLOTA 1103554 305549 Sonora Imuris CAMPO CARRETERO 1105111 304617 Sonora Imuris LA CANTINA 1104736 304757 Sonora Imuris LA CASITA 1105304 310005 Sonora Imuris CERRO BLANCO 1105020 304927 Sonora Imuris EL COYOTE (LA QUIRUGUEÑA) 1104840 304718 Sonora Imuris LAS CRUCES 1104901 304705 Sonora Imuris LA ESTACIÓN 1105220 304638 Sonora Imuris EL FRESNAL 1105243 304840 Sonora Imuris LOS JANOS 1105003 305014 Sonora Imuris LA LAGUNA 1104901 304639 Sonora Imuris LA MESA 1105433 304443 Sonora Imuris PUERTA DEL CAJÓN 1104559 304826 Sonora Imuris EL SALTO 1104655 304733 Sonora Imuris TERRENATE 1105518 304340 Sonora Imuris LAS VIGUITAS 1105048 304845 Sonora Imuris EL POZO 1110052 305829 Sonora Imuris LA VÍBORA 1105843 305554 Sonora Imuris EL CRUCERO 1105220 304623 Sonora Imuris LA CASA DE PIEDRA 1104810 304738 Sonora Imuris LOS VALLECITOS 1105521 305238 Sonora Imuris EL CAMPITO (LA NOPALERA) 1105054 305306 Sonora Imuris LAS PLAYITAS 1105158 305500 Sonora Imuris EL QUELITAL 1105201 305402 Sonora Imuris LA CHICOLITA 1105050 304819 Sonora Imuris YERBABUENA 1105325 304557 Sonora Imuris ESTACIÓN CUMERAL 1105105 305314 Sonora Imuris LA QUINTA 1104654 304808 Sonora Imuris CAÑADA DEL DIABLO 1105037 304621 Sonora Imuris EL RANCHITO 1105307 304604 Sonora Imuris LAS FLORES 1105101