Wildlife Management Practices Associated with Pathogen Exposure in Non-Native Wild Pigs in Florida, U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antelope, Deer, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goats: a Guide to the Carpals

J. Ethnobiol. 10(2):169-181 Winter 1990 ANTELOPE, DEER, BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOATS: A GUIDE TO THE CARPALS PAMELA J. FORD Mount San Antonio College 1100 North Grand Avenue Walnut, CA 91739 ABSTRACT.-Remains of antelope, deer, mountain goat, and bighorn sheep appear in archaeological sites in the North American west. Carpal bones of these animals are generally recovered in excellent condition but are rarely identified beyond the classification 1/small-sized artiodactyl." This guide, based on the analysis of over thirty modem specimens, is intended as an aid in the identifi cation of these remains for archaeological and biogeographical studies. RESUMEN.-Se han encontrado restos de antilopes, ciervos, cabras de las montanas rocosas, y de carneros cimarrones en sitios arqueol6gicos del oeste de Norte America. Huesos carpianos de estos animales se recuperan, por 10 general, en excelentes condiciones pero raramente son identificados mas alIa de la clasifi cacion "artiodactilos pequeno." Esta glia, basada en un anaIisis de mas de treinta especlmenes modemos, tiene el proposito de servir como ayuda en la identifica cion de estos restos para estudios arqueologicos y biogeogrMicos. RESUME.-On peut trouver des ossements d'antilopes, de cerfs, de chevres de montagne et de mouflons des Rocheuses, dans des sites archeologiques de la . region ouest de I'Amerique du Nord. Les os carpeins de ces animaux, generale ment en excellente condition, sont rarement identifies au dela du classement d' ,I artiodactyles de petite taille." Le but de ce guide base sur 30 specimens recents est d'aider aidentifier ces ossements pour des etudes archeologiques et biogeo graphiques. -

Gallina & Mandujano

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol. 2 (2):116-127, 2009 Special issue: introduction Research on ecology, conservation and management of wild ungulates in Mexico Sonia Gallina1 and Salvador Mandujano1 1 Departamento de Biodiversidad y Ecología Animal, Instituto de Ecología A. C., km. 2.5 Carret. Ant. Coatepec No. 351, Congregación del Haya, Xalapa 91070, Ver. México. E‐mail: <[email protected]>; <[email protected]> Abstract This special issue of Tropical Conservation Science provides a synopsis of nine of the eleven presentations on ungulates presented at the Symposium on Ecology and Conservation of Ungulates in Mexico during the Mexican Congress of Ecology held in November 2008 in Merida, Yucatan. Of the eleven species of wild ungulates in Mexico (Baird´s tapir Tapirus bairdii, pronghorn antelope Antilocapra americana, American bison Bison bison, bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis, elk Cervus canadensis, red brocket deer Mazama temama, Yucatan brown brocket Mazama pandora, mule deer Odocoileus hemionus, white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus, white-lipped peccary Tayassu pecari and collared peccary Pecari tajacu), studies which concern four of these species are presented: Baird’s tapir and the white lipped peccary, which are tropical species in danger of extinction; the bighorn sheep, of high value for hunting in the north-west; and the white-tailed deer, the most studied ungulate in Mexico due to its wide distribution in the country and high hunting and cultural value. In addition, two studies of exotic species, wild boar (Sus scrofa) and red deer (Cervus elaphus), are presented. Issues addressed in these studies are: population estimates, habitat use, evaluation of UMA (Spanish acronym for ‘Wildlife Conservation, Management and Sustainable Utilization Units’) and ANP (Spanish acronym for ‘Natural Protected Areas’) to sustain minimum viable populations, and the effect of alien species in protected areas and UMA, all of which allow an insight into ungulate conservation and management within the country. -

THE WHITE-TAILED DEER of NORTH AMERICA by Walter P. TAYLOR, United States Department of the Interior, Retired

THE WHITE-TAILED DEER OF NORTH AMERICA By Walter P. TAYLOR, United States Department of the Interior, Retired " By far the most popular and widespread of North America's big game animais is the deer, genus Odocoileus. Found from Great Slave Lake and the 60th parallel of latitude in Canada to Panama and even into northern South America, and from the Atlantic to the Pacifie, the deer, including the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virgi nianus ssp., see map.) and the mule deer, (Odocoileus hemionus ssp.) with, of course, the coast deer of the Pacifie area (a form of hemionus), is characterized by a geographic range far more extensive than any other big game mammal of our continent. Within this tremendous area the deer occurs in a considerable variety of habitats, being found in appro priate locations from sea level to timberline in the moun tains, and in all the life zones from Tropical to Hudsonian. The whitetail is found in the swamps of Okefinokee, in the grasslands of the Gulf Coast, in the hardwood forests of the east, and in the spruce-fir-hemlock woodlands of the western mountains. It inhabits plains country, rocky plateaus, and rough hilly terrain. The deer resembles the coyote, the raccoon, the opos sum and the gray fox in its ability to adapt itself suffi ciently to the settlements of mankind to survive and even to spread, within the boundaries of cities. It is one of the easiest of all the game animais to maintain. It is also one of the most valuable of all our species of wildlife, * This paper is based on «The Deer of North America» edited by Walter P. -

Cervid Mixed-Species Table That Was Included in the 2014 Cervid RC

Appendix III. Cervid Mixed Species Attempts (Successful) Species Birds Ungulates Small Mammals Alces alces Trumpeter Swans Moose Axis axis Saurus Crane, Stanley Crane, Turkey, Sandhill Crane Sambar, Nilgai, Mouflon, Indian Rhino, Przewalski Horse, Sable, Gemsbok, Addax, Fallow Deer, Waterbuck, Persian Spotted Deer Goitered Gazelle, Reeves Muntjac, Blackbuck, Whitetailed deer Axis calamianensis Pronghorn, Bighorned Sheep Calamian Deer Axis kuhili Kuhl’s or Bawean Deer Axis porcinus Saurus Crane Sika, Sambar, Pere David's Deer, Wisent, Waterbuffalo, Muntjac Hog Deer Capreolus capreolus Western Roe Deer Cervus albirostris Urial, Markhor, Fallow Deer, MacNeil's Deer, Barbary Deer, Bactrian Wapiti, Wisent, Banteng, Sambar, Pere White-lipped Deer David's Deer, Sika Cervus alfredi Philipine Spotted Deer Cervus duvauceli Saurus Crane Mouflon, Goitered Gazelle, Axis Deer, Indian Rhino, Indian Muntjac, Sika, Nilgai, Sambar Barasingha Cervus elaphus Turkey, Roadrunner Sand Gazelle, Fallow Deer, White-lipped Deer, Axis Deer, Sika, Scimitar-horned Oryx, Addra Gazelle, Ankole, Red Deer or Elk Dromedary Camel, Bison, Pronghorn, Giraffe, Grant's Zebra, Wildebeest, Addax, Blesbok, Bontebok Cervus eldii Urial, Markhor, Sambar, Sika, Wisent, Waterbuffalo Burmese Brow-antlered Deer Cervus nippon Saurus Crane, Pheasant Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Hog Deer, Sambar, Barasingha, Nilgai, Wisent, Pere David's Deer Sika 52 Cervus unicolor Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Barasingha, Nilgai, Rusa, Sika, Indian Rhino Sambar Dama dama Rhea Llama, Tapirs European Fallow Deer -

Metacarpal Bone Strength of Pronghorn (Antilocapra Americana) Compared to Mule

Metacarpal Bone Strength of Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) compared to Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) by ANDREW J BARAN B.A. Western State Colorado University, 2013 A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Sciences Department of Biology 2018 © Copyright by Andrew J Baran 2018 All Rights Reserved This thesis for the Master of Sciences degree by Andrew J Baran has been approved for the Department of Biology by Jeffrey P Broker, Chair Emily H Mooney Helen K Pigage November 21, 2018 Date ii Baran, Andrew J (M.Sc., Biology) Metacarpal Bone Strength of Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) compared to Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) Thesis directed by Associate Professor Jeffrey P Broker ABSTRACT Human-made barriers influence the migration patterns of many species. In the case of the pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), a member of the Order Artiodactyla and native to the central and western prairies of the United States, the presence of fences may completely inhibit movement. Depending on the fence a pronghorn will rarely decide to jump over it, instead preferring to crawl under, if possible, or negotiate around it until the animal finds an opening. Despite having been observed to jump an 8-foot-tall fence in a previous study, some block exists. This study investigated one possible block, being the risk of breakage on the lower extremity bones upon landing. The metacarpals of pronghorn and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), a routine jumper of fences that lives in relative proximity to the pronghorn, were tested using a three-point bending test. -

Disease Background & Health Implications

Animals play essential roles in the environment and provide many important benefits to ecosystem health. One Health is this recognition that animal health, human health, and environmental health are all linked. Similar to people, wild and domestic animals can be victims of disease. The information presented here is intended to promote awareness and provide background for certain diseases that wildlife may get. See the Guidance for Park Visitors section below for tips to safely enjoy your national park trip. Disease Background & Health Implications: Epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) is a native disease that causes significant morbidity and mortality among deer in North America. The disease is caused by EHD viruses. The virus is transmitted primarily by biting midges (small flies) of the genus Culicoides. The incubation period for disease to develop in deer is 5-10 days. Species Affected: EHD causes disease in wild ruminants. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are the most commonly affected wild ruminant and often die as a result of infection. Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana), and elk (Cervus canadensis) have been documented with clinical signs, although less frequently. Antibodies indicating exposure to disease have been detected in other wild ruminants (black- tailed deer, red deer, fallow deer, roe deer). Clinical Signs: Common signs of initial infection include depression, fever, respiratory distress, and swelling of the head, neck, and tongue. Affected deer often remain near water sources. Following recovery from acute disease, deer with chronic disease can develop breaks and growth interruptions in the hooves progressing to complete sloughing of the hoof wall. Hoof lesions will present as lameness (can be seen in colder months after typical transmission periods have passed) that can cause severely affected individuals to attempt walking on the knees or chest. -

Competition for Food Between Mule Deer and Bighorn Sheep on Rock Creek Winter Range Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1969 Competition for food between mule deer and bighorn sheep on Rock Creek Winter Range Montana Allen Cooperrider The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cooperrider, Allen, "Competition for food between mule deer and bighorn sheep on Rock Creek Winter Range Montana" (1969). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6736. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6736 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPETITION FOR FOOD BETWEEN MULE DEER AND BIGHORN SHEEP ON ROCK CREEK WINTER RANGE, MONTANA By- Allen Y, Cooperrlder B.A., University of California, I967 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1969 Approved by: Chairman) Board of T Date X ' ' Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP37537 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Orf Virus Infection in Alaskan Mountain Goats, Dall's Sheep, Muskoxen

Tryland et al. Acta Vet Scand (2018) 60:12 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-018-0366-8 Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica RESEARCH Open Access Orf virus infection in Alaskan mountain goats, Dall’s sheep, muskoxen, caribou and Sitka black‑tailed deer Morten Tryland1* , Kimberlee Beth Beckmen2, Kathleen Ann Burek‑Huntington3, Eva Marie Breines1 and Joern Klein4* Abstract Background: The zoonotic Orf virus (ORFV; genus Parapoxvirus, Poxviridae family) occurs worldwide and is transmit‑ ted between sheep and goats, wildlife and man. Archived tissue samples from 16 Alaskan wildlife cases, representing mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus, n 8), Dall’s sheep (Ovis dalli dalli, n 3), muskox (Ovibos moschatus, n 3), Sitka black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus= sitkensis, n 1) and caribou (Rangifer= tarandus granti, n 1), were analyzed.= = = Results: Clinical signs and pathology were most severe in mountain goats, afecting most mucocutaneous regions, including palpebrae, nares, lips, anus, prepuce or vulva, as well as coronary bands. The proliferative masses were solid and nodular, covered by dark friable crusts. For Dall’s sheep lambs and juveniles, the gross lesions were similar to those of mountain goats, but not as extensive. The muskoxen displayed ulcerative lesions on the legs. The caribou had two ulcerative lesions on the upper lip, as well as lesions on the distal part of the legs, around the main and dew claws. A large hairless spherical mass, with the characteristics of a fbroma, was sampled from a Sitka black-tailed deer, which did not show proliferative lesions typical of an ORFV infection. Polymerase chain reaction analyses for B2L, GIF, vIL-10 and ATI demonstrated ORFV specifc DNA in all cases. -

Smithsonian Field Guide: Cervidae

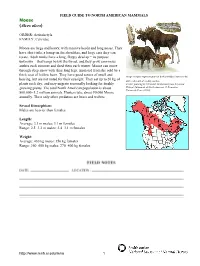

FIELD GUIDE TO NORTH AMERICAN MAMMALS Moose (Alces alces) ORDER: Artiodactyla FAMILY: Cervidae Moose are large and heavy, with massive heads and long noses. They have short tails, a hump on the shoulders, and large ears they can rotate. Adult males have a long, floppy dewlap − its purpose unknown − that hangs below the throat, and they grow enormous antlers each summer and shed them each winter. Moose can move through deep snow with their long legs, insulated from the cold by a thick coat of hollow hairs. They have good senses of smell and Image includes representation of bark shredded from tree by hearing, but are not noted for their eyesight. They eat up to 20 kg of antler rubs and of muddy wallow plants each day, and may migrate seasonally looking for freshly Credit: painting by Elizabeth McClelland from Kays and growing plants. The total North American population is about Wilson's Mammals of North America, © Princeton University Press (2002) 800,000−1.2 million animals. Hunters take about 90,000 Moose annually. Their only other predators are bears and wolves Sexual Dimorphism: Males are heavier than females. Length: Average: 3.1 m males; 3.1 m females Range: 2.5−3.2 m males; 2.4−3.1 m females Weight: Average: 430 kg males; 350 kg females Range: 360−600 kg males; 270−400 kg females http://www.mnh.si.edu/mna 1 FIELD GUIDE TO NORTH AMERICAN MAMMALS Elk (Cervus elaphus) ORDER: Artiodactyla FAMILY: Cervidae There are more than 750,000 Elk today, many living on federally protected lands in the United States and Canada. -

Description, Taphonomy, and Paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene Peccaries (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) from Bat Cave, Pulaski County, Missouri Aaron L

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2016 Description, Taphonomy, and Paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene Peccaries (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) from Bat Cave, Pulaski County, Missouri Aaron L. Woodruff East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Woodruff, Aaron L., "Description, Taphonomy, and Paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene Peccaries (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) from Bat Cave, Pulaski County, Missouri" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3051. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3051 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Description, Taphonomy, and Paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene Peccaries (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) from Bat Cave, Pulaski County, Missouri _____________________________ A thesis presented to the Department of Geosciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Geosciences _____________________________________ by Aaron Levi Woodruff May 2016 _______________________________ Dr. Blaine W. Schubert Dr. Jim I. Mead Dr. Steven C. Wallace Keywords: Pleistocene, Peccaries, Platygonus compressus, Canis dirus, Taphonomy, Paleoecology, Bat Cave ABSTRACT Description, Taphonomy, and Paleoecology of Late Pleistocene Peccaries (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) from Bat Cave, Pulaski County, Missouri by Aaron Levi Woodruff The late Pleistocene faunal assemblage from Bat Cave, central Ozarks, Missouri provides an opportunity to assess specific aspects of behavior, ecology, and ontogeny of the extinct peccary Platygonus compressus. -

Mule Deer (Odocoileus Hemionus)

Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) February 2006 Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet Number 28 General information The mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) is a member of the family Cervidae, which is characterized by hoofed mammals that shed their antlers annually. The mule deer is one of only a handful of large herbivores in North America that survived the great extinctions of about 7,000 to 12,000 years ago. The name mule deer is in reference to the animal’s relatively large ears and robust body form, at least in comparison to the more slender structure of its close relative, the white-tailed deer. Mature bucks weigh 150 to 200 pounds on average, though some may ex- National Park Service ceed 300 pounds. Does are noticeably smaller than Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) bucks, ranging from 100 to 150 pounds at maturi- This leaflet is intended to serve as a basic introduc- ty. The coat color of the mule deer is seasonal, turn- tion to mule deer habitat requirements and assist pri- ing from a reddish-brown in summer to a blue-gray in vate landowners and managers in developing man- winter. Although shading is variable, mule deer gen- agement plans for mule deer. The success of any erally have light colored faces, throats, bellies, inner individual species management plan depends on tar- leg surfaces, and rump patches. The tail is short, nar- geting the particular requirements of the species in row, and white with a black tip and, unlike the white- question, evaluating the designated habitat area to en- tailed deer, is not raised when the animal is alarmed. -

Population-Level Effects of Immunocontraception in White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus Virginianus)

CSIRO PUBLISHING Wildlife Research, 2008, 35, 494–501 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/wr Population-level effects of immunocontraception in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) A,C B Allen T. Rutberg and Ricky E. Naugle ADepartment of Environmental and Population Health, Tufts–Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, 200 Westboro Road, North Grafton, MA 01536, USA. BThe Humane Society of the United States, 700 Professional Drive, Gaithersburg, MD 20879, USA. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. In North America, dense populations of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in suburbs, cities and towns have stimulated a search for new population-management tools. Most research on deer contraception has focused on the safety and efficacy of immunocontraceptive vaccines, but few studies have examined population-level effects. We report here results from two long-term studies of population effects of the porcine zona pellucida (PZP) immunocontraceptive vaccine, at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA, and at Fire Island National Seashore (FIIS), New York, USA. Annual population change at NIST was strongly correlated with population fertility (rP = 0.82, P = 0.001); when population fertility at NIST dropped below 0.40 fawns per female, the population declined. Contraceptive treatments at NIST were associated with a 27% decline in population between 1997 and 2002, and fluctuated thereafter with the effectiveness of contraceptive treatments. In the most intensively treated segment of FIIS, deer population density declined by ~58% between 1997 and 2006. These studies demonstrate that, in principle, contraception can significantly reduce population size. Its usefulness as a management tool will depend on vaccine effectiveness, accessibility of deer for treatment, and site-specific birth, death, immigration, and emigration rates.