Early Medieval Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

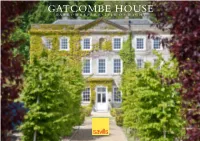

Gatcombe House G a T C O M B E P a R K • I S L E O F W I G H T Gatcombe House Gatcombe Park • Isle of Wight

GATCOMBE HOUSE G A T C O M B E P A R K • I S L E O F W I G H T GATCOMBE HOUSE GATCOMBE PARK • ISLE OF WIGHT Newport: 3 miles • Cowes 9 miles • Fishbourne Ferry 9.5 miles (Portsmouth Harbour from 45 mins) Battersea Heliport 35 mins (All mileages and time approximate) An exemplar of Georgian elegance ACCOMMODATION Entrance porch • Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Billiard room • Study • Office Sitting room • Gymnasium • Kitchen/breakfast room • Preparation kitchen • Staircase hall Utility room • Cloakroom • Extensive cellars Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom and dressing room with separate loo Two further bedrooms with adjoining bathrooms • Additional six bedrooms and bathrooms One bedroom staff flat • Studio The Coach House: Entrance hall • Kitchen/living room • Sitting room • Utility room • Loo Artist’s studio • Two studies • Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom Three further bedrooms and bathroom • Garden Stable Cottage: Entrance hall • Kitchen/living room • Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom Two further bedrooms and bathroom • Loo • Garden Formal gardens and lawns • Rose garden • Parkland • Pastureland • Woodland Walled courtyard with greenhouse and herb borders • Ornamental lake • Specimen and ornamental trees Grade II listed bridge • Swimming Pool • Pavilion • Tennis court • Garaging and outbuildings Extensive agricultural buildings with adjoining field In all about 48 acres (19.35 hectares) George Nares Steven Moore Savills Country Department Savills Winchester [email protected] [email protected] 020 7016 3822 01962 834 010 Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text HISTORY Gatcombe Park estate has an exciting and colourful history with records preceding the Norman Conquest and the village of Gatcombe is listed in the Domesday Book. -

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected]

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected] Chillerton & Rookley Primary Godshill Primary Main Road, Chillerton School Road, Godshill Isle of Wight, PO30 3EP Isle of Wight, PO38 3HJ Tel. 01983 721207 Tel. 01983 840246 [email protected] [email protected] Wednesday 14th July 2021 Re: Godshill Class Structure for September 2021 Dear Parents and Carers, We are really looking forward to the end of term and a well-earned rest. Many of you will be wanting to know which classes and teachers your children will be having. The class structure for September will be: Class Class Name Teacher / Lead Support Staff Entrance to School Nursery Bembridge Windmill Marie Seaman Jim Palmer Nursery Gate Kate McKenzie Alana Monroe Reception Calbourne Mill Mrs Polly Smith Dawn Sargent Reception Gate – Lizzie Burden Car park Year 1/2 Osbourne House Miss Kirsty Hart Wendy Whitewood Main Entrance Year 2/3 The Needles Mr Conner Knight Lisa Young Main Entrance Brogan Bodman Year 4/5 Carisbrooke Castle Mrs Westhorpe and Jodie Wendes Car park side Mrs Tombleson entrance Year 5 Yarmouth Castle Mr Tim Smith Chantelle De’ath Steps side of school Lauren Shaw-Yates Year 6 St Catherine’s Mrs Boakes Danny Chapman Steps side of school Oratory Any pupils that are in the mixed class of Year 1/2 or 4/5 that are in Year 2 or 5 will be contacted individually by the school. School will start at 8:45am for all pupils. School finishes for all pupils at 3:00pm, except for Reception, who will finish at 2:55pm. -

Three Early Anglo-Saxon Metalwork Finds from the Isle of Wight, 1993-6

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 53, 1998,109-119 (Hampshire Studies 1998) THREE EARLY ANGLO-SAXON METALWORK FINDS FROM THE ISLE OF WIGHT, 1993-6 .ByMARKSTEDMAN ABSTRACT A Cruciform Brooch, a Disc Brooch and a Frank- Description ish/Merovingian Bronze Bowl are discussed in the light of Though incomplete in form the object under ex the relationship between Late Roman villas and Early amination has a grey green patina which exhibits a Anglo-Saxon cemeteries and settlements. TheirJindspots arehig h degree of scratch and wear. However the also commented upon in regard to the suggested reuse of artefact fortunately seems free of any active corro Bronze Age download barrow cemeteries as properly sion. In its damaged state, from the top knob- boundary markers. The Island's Early Anglo-Saxon settle- headed terminal to the break in the artefact's 'bow' ment,focusing upon downland springlmes, is also discussed. spine, it measures 47.5 mm in length. The object seems to have suffered damage in antiquity, since the breaks in the artefact are not clean. Its bow 'spine' is gendy angled within the front piece, yet A CRUCIFORM BROOCH FROM the foot plate is missing below the break. It is of BLOODSTONE COPSE, solid construction, rather than being hollow in EAGLEHEAD DOWN, NEAR RYDE form, which could suggest that the artefact was an (Figsl&2) earlier variant or of a localised type (Eagles 1993, 133). On 9 August, 1995, a Mr Beeney brought a series The foot plate of the brooch is missing below of artefacts to the Isle of Wight Archaeological the break in the bow, which in turn has been Centre for identification purposes. -

Planning and Infrastructure Services

PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES The following planning applications and appeals have been submitted to the Isle of Wight Council and can be viewed online www.iow.gov.uk/planning using the Public Access link. Alternatively they can be viewed at Seaclose Offices, Fairlee Road, Newport, Isle of Wight, PO30 2QS. Office Hours: Monday – Thursday 8.30 am – 5.00 pm Friday 8.30 am – 4.30 pm Comments on the applications must be received within 21 days from the date of this press list, and comments for agricultural prior notification applications must be received within 7 days to ensure they be taken into account within the officer report. Comments on planning appeals must be received by the Planning Inspectorate within 5 weeks of the appeal start date (or 6 weeks in the case of an Enforcement Notice appeal). Details of how to comment on an appeal can be found (under the relevant LPA reference number) at www.iow.gov.uk/planning. For householder, advertisement consent or minor commercial (shop) applications, in the event of an appeal against a refusal of planning permission, representations made about the application will be sent to Planning Inspectorate, and there will be no further opportunity to comment at appeal stage. Should you wish to withdraw a representation made during such an application, it will be necessary to do so in writing within 4 weeks of the start of an appeal. All written representations relating to applications will be made available to view online. PLEASE NOTE THAT APPLICATIONS WHICH FALL WITHIN MORE THAN ONE PARISH OR -

Selfbuild Register Extract

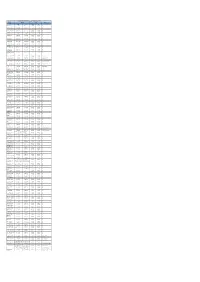

Address 4 When Ready Adults Children Individual Property Size Parishes Date Added Beds 1 - 2 years 2 0 3 bedroom property Bembridge | East Cowes | Nettlestone and Seaview 22/02/2018 Dorset within 1 year 2 0 2 bedroom property Sandown | Shanklin | Ventnor 13/04/2016 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Nettlestone and Seaview | Ryde | St Helens 21/04/2016 Isle of Wight 3 - 5 years 0 0 3 bedroom property Freshwater | Gurnard | Totland 22/04/2016 within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Brighstone | Freshwater | Niton and Whitwell 08/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 3 0 2 bedroom property Ryde | Sandown | St Helens 21/04/2016 Leicestershire 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Bembridge | Freshwater | St Helens 20/03/2017 Leics within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Brighstone | Totland | Yarmouth 20/03/2017 1 - 2 years 5 0 4 bedroom property Cowes | Gurnard 15/08/2016 London within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Bembridge | Ryde | St Helens 07/08/2018 London within 1 year 2 0 4 bedroom property Ryde | Shanklin | Ventnor 13/03/2017 Isle Of Wight 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Chale | Freshwater | Totland 08/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property East Cowes | Newport | Wroxall 22/04/2016 Isle Of Wight 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Freshwater | Shalfleet | Yarmouth 10/02/2017 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Gurnard | Newport | Northwood 11/04/2016 Isle of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Fishbourne | Havenstreet and Ashey | Wootton 22/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 3 0 3 bedroom property -

Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for West Wight Chalk Downland. INTRODUCTION The West Wight Chalk Downland HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography and historic landscape character. It forms the western half of a central chalk ridge that crosses the Isle of Wight, the eastern half having been defined as the East Wight Chalk Ridge . Another block of Chalk and Upper Greensand in the south of the Isle of Wight has been defined as the South Wight Downland . Obviously there are many similarities between these three HEAP Areas. However, each of the Areas occupies a particular geographical location and has a distinctive historic landscape character. This document identifies essential characteristics of the West Wight Chalk Downland . These include the large extent of unimproved chalk grassland, great time-depth, many archaeological features and historic settlement in the Bowcombe Valley. The Area is valued for its open access, its landscape and wide views and as a tranquil recreational area. Most of the land at the western end of this Area, from the Needles to Mottistone Down, is open access land belonging to the National Trust. Significant historic landscape features within this Area are identified within this document. The condition of these features and forces for change in the landscape are considered. Management issues are discussed and actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. -

Little Budbridge, Budbridge Lane, Merstone, Isle Of

m LITTLE BUDBRIDGE, BUDBRIDGE LANE, MERSTONE, ISLE OF WIGHT PO30 3DH GUIDE PRICE £1,545,000 A beautifully restored, 5 bedroom period country house, occupying grounds about 7.5 acres in a quiet yet accessible rural location. Restored to an exceptional standard, this small manor house is constructed largely of local stone elevations beneath hand-made clay peg tiled roofs. It is Grade II listed with origins in the 13th Century, and with a date stone from 1731. Included are the neighbouring barns and outbuildings which have consent for several holiday letting units. After a period of gentle decline the property was virtually derelict in 2013 and in 2013-15 it underwent a programme of complete renovation, extension, improvement and under the supervision of the conservation team of the Local Authority. Modern high-quality kitchen and bathroom fittings by 'Porcelanosa' have been installed to sympathetically compliment the many original period features. The finest original materials and craftsman techniques have been used and finished to a high standard. The house enjoys an elevated position within about 7.5 acres of grounds with extensive vistas across the beautiful surrounding countryside of the Arreton Valley to downland beyond. The gardens have been terraced, landscaped and enclosed in new traditional wrought-iron parkland fencing, with matching entrance gates, beyond which are lakes and a grass tennis court. The property is set beside a quiet "no through" lane within a picturesque rural location, yet is easily accessible to Newport, (4 miles) with mainland ferry links to Portsmouth 6.5 miles away at Fishbourne. Ryde School is also easily accessible about 8 miles away. -

The Gurnard Roman Villa

Island Sites Revisited The Gurnard Roman Villa by C. T. WlTHERBY GENERAL NOTE HIS building was discovered in 1864 by Mr Edwin Joseph Smith and it is described by the Rev Edmund Kell, M.A., F.S.A., in the British Archaeological Association Reports T for 1866 (p. 351). This report, which includes a copy of the plan of the building prepared by Mr Smith, shows that parts of three rooms were found, the rooms running east and west. The original of Mr Smith's plan is held by the Cowes Urban District Council at Northwood House, Cowes. The whole of the villa has now been destroyed by the sea. EXACT POSITION This is not easy to determine, because Mr Smith's plan does not show any surface feature other than a hedge and the sea has encroached very greatly since 1866. However, the writer suggests that the most easterly of the three rooms of the villa was about 30 yards west, or north-west, of Marsh Cottage, Gurnard, which is itself about 50 yards north of the bridge over the Gurnard Luck. The site is two miles west of Cowes. The evidence to support this is as follows: (a) In his account, Mr Fell refers to the fact that traces of the villa ' appear to enter the garden of the nearby cottage', and later he mentions that a Mrs Grist lived in the cottage in 1866. (Jb) The writer has been informed by Mr Gladstone Flux, of Rew Street, Gurnard, that his grandfather told him that Marsh Cottage was built by a Mr Grist or Grisk. -

Scheme of Polling Districts As of June 2019

Isle of Wight Council – Scheme of Polling Districts as of June 2019 Polling Polling District Polling Station District(s) Name A1 Arreton Arreton Community Centre, Main Road, Arreton A2 Newchurch All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch A3 Apse Heath All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch AA Ryde North West All Saints Church Hall, West Street, Ryde B1 Binstead Binstead Methodist Schoolroom, Chapel Road, Binstead B2 Fishbourne Royal Victoria Yacht Club, 91 Fishbourne Lane BB1 Ryde South #1 5th Ryde Scout Hall, St Johns Annexe, St Johns Road, Ryde BB2 Ryde South #2 Ryde Fire Station, Nicholson Road C1 Brading Brading Town Hall, The Bull Ring, High Street C2 St. Helens St Helens Community Centre, Guildford Road, St. Helens C3 Bembridge North Bembridge Village Hall, High Street, Bembridge C4 Bembridge South Bembridge Methodist Church Hall, Foreland Road, Bembridge CC1 Ryde West#1 The Sherbourne Centre, Sherbourne Avenue CC2 Ryde West#2 Ryde Heritage Centre, Ryde Cemetery, West Street D1 Carisbrooke Carisbrooke Church Hall, Carisbrooke High Street, Carisbrooke Carisbrooke and Gunville Methodist Schoolroom, Gunville Road, D2 Gunville Gunville DD1 Sandown North #1 The Annexe, St Johns Church, St. Johns Road Sandown North #2 - DD2 Yaverland Sailing & Boating Club, Yaverland Road, Sandown Yaverland E1 Brighstone Wilberforce Hall, North Street, Brighstone E2, E3 Brook & Mottistone Seely Hall, Brook E4 Shorwell Shorwell Parish Hall, Russell Road, Shorwell E5 Gatcombe Chillerton Village Hall, Chillerton, Newport E6 Rookley Rookley Village -

WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP of the WIGHT Experience Sustainable Transport

BE A WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP OF THE WIGHT Experience sustainable transport Portsmouth To Southampton s y s rr Southsea Fe y Cowe rr Cowe Fe East on - ssenger on - Pa / e assenger l ampt P c h hi Southampt Ve out S THE EGYPT POINT OLD CASTLE POINT e ft SOLENT yd R GURNARD BAY Cowes e 5 East Cowes y Gurnard 3 3 2 rr tsmouth - B OSBORNE BAY ishbournFe de r Lymington F enger Hovercra Ry y s nger Po rr as sse Fe P rtsmouth/Pa - Po e hicl Ve rtsmouth - ssenger Po Rew Street Pa T THORNESS AS BAY CO RIVE E RYDE AG K R E PIER HEAD ERIT M E Whippingham E H RYDE DINA N C R Ve L Northwood O ESPLANADE A 3 0 2 1 ymington - TT PUCKPOOL hic NEWTOWN BAY OO POINT W Fishbourne l Marks A 3 e /P Corner T 0 DODNOR a 2 0 A 3 0 5 4 Ryde ssenger AS CREEK & DICKSONS Binstead Ya CO Quarr Hill RYDE COPSE ST JOHN’S ROAD rmouth Wootton Spring Vale G E R CLA ME RK I N Bridge TA IVE HERSEY RESERVE, Fe R Seaview LAKE WOOTTON SEAVIEW DUVER rr ERI Porcheld FIRESTONE y H SEAGR OVE BAY OWN Wootton COPSE Hamstead PARKHURST Common WT FOREST NE Newtown Parkhurst Nettlestone P SMALLBROOK B 4 3 3 JUNCTION PRIORY BAY NINGWOOD 0 SCONCE BRIDDLESFORD Havenstreet COMMON P COPSES POINT SWANPOND N ODE’S POINT BOULDNOR Cranmore Newtown deserted HAVENSTREET COPSE P COPSE Medieval village P P A 3 0 5 4 Norton Bouldnor Ashey A St Helens P Yarmouth Shaleet 3 BEMBRIDGE Cli End 0 Ningwood Newport IL 5 A 5 POINT R TR LL B 3 3 3 0 YA ASHEY E A 3 0 5 4Norton W Thorley Thorley Street Carisbrooke SHIDE N Green MILL COPSE NU CHALK PIT B 3 3 9 COL WELL BAY FRES R Bembridge B 3 4 0 R I V E R 0 1 -

ROAD OR PATH NAME from to from to High Street, Ventnor

ROAD AND PATH CLOSURES (28th September 2020 ‐ 4th October 2020) ROAD OR LOCATION DATE DETAILS PATH NAME FROM TO FROM TO High Street, Ventnor Spring Hill Albert Street 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Newport Road, Ventnor Gills Cliff Road Down Lane 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP High Street, Yarmouth Market Square Basketts Lane 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Old Seaview Lane, Seaview Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP St Martins Road, Wroxall Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Ranelagh Road, Lake Lake Hill Cliff Road 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Albert Street, Ryde Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Prince Street, Ryde Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Upton Road, Ryde Partlands Avenue William Street 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Park Road, Ryde Dover Street Monkton Street 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Westhill Road, Ryde St Johns Avenue Alexandra Road 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Pellhurst Road, Ryde Upton Road Partlands Avenue 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP St Johns Wood Road, Ryde St Johns Hill Park Road 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Heathfield Road, Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Freshwater Princes Road, Freshwater The Avenue Colwell Road 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Elm Close, Freshwater Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP St Lawrence Shute, Entire Length Entire Length 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Whitwell Kings Road & Embankment Latimer Road Church Road 02.10.2020 13.11.2020 CIP Road, Bembridge Military Road, Isle of Wight Church Place Brook Road 27.09.2020 -

HEAP for Isle of Wight Rural Settlement

Isle of Wight Parks, Gardens & Other Designed Landscapes Historic Environment Action Plan Isle of Wight Gardens Trust: March 2015 2 Foreword The Isle of Wight landscape is recognised as a source of inspiration for the picturesque movement in tourism, art, literature and taste from the late 18th century but the particular significance of designed landscapes (parks and gardens) in this cultural movement is perhaps less widely appreciated. Evidence for ‘picturesque gardens’ still survives on the ground, particularly in the Undercliff. There is also evidence for many other types of designed landscapes including early gardens, landscape parks, 19th century town and suburban gardens and gardens of more recent date. In the 19th century the variety of the Island’s topography and the richness of its scenery, ranging from gentle cultivated landscapes to the picturesque and the sublime with views over both land and sea, resulted in the Isle of Wight being referred to as the ‘Garden of England’ or ‘Garden Isle’. Designed landscapes of all types have played a significant part in shaping the Island’s overall landscape character to the present day even where surviving design elements are fragmentary. Equally, it can be seen that various natural components of the Island’s landscape, in particular downland and coastal scenery, have been key influences on many of the designed landscapes which will be explored in this Historic Environment Action Plan (HEAP). It is therefore fitting that the HEAP is being prepared by the Isle of Wight Gardens Trust as part of the East Wight Landscape Partnership’s Down to the Coast Project, particularly since well over half of all the designed landscapes recorded on the Gardens Trust database fall within or adjacent to the project area.