Three Case Studies / by Cheryl L. Macdonald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regular Meeting of the Wayne Township Board of Education Was

Regular Meeting Minutes April 23, 2015 Page 1 01311 BOARD OF EDUCATION WAYNE TOWNSHIP PUBLIC SCHOOLS WAYNE, NEW JERSEY REGULAR BOARD MEETING April 23, 2015 The Regular Meeting of the Wayne Township Board of Education was held on Thursday, April 23, 2015 in the Council Chambers of the Municipal Building at 475 Valley Road, Wayne, New Jersey 07470. The Executive Session was held in the Administration Building Conference Room, 50 Nellis Drive, Wayne, New Jersey 07470. The meeting was scheduled to begin at 6:00 p.m. pursuant to the terms of the Sunshine Law. The meeting was called to order at 6:03 p.m. by Mrs. Eileen Albanese, Board President. Reading of "Sunshine Law" Statement Adequate notice of this Regular and Executive Meeting, setting forth time, date and location, has been provided in accordance with the requirements of the Open Public Meetings Act on January 9, 2015 by: Prominently posting a copy on the bulletin board in the lobby of the offices of the Board of Education, which is a public place reserved for such announcements, transmitting a copy of this notice to The Record, The Wayne Today, and the Municipal Clerk. Roll Call PRESENT: Eileen Albanese, Mitch Badiner, Michael Bubba, Robert Ceberio, Kim Essen, Cathy Kazan, Allan Mordkoff, Donald Pavlak and Christian Smith. ALSO PRESENT: Dr. Mark Toback, Superintendent, Michael Ben-David, Assistant Superintendent, Juanita A. Petty, RSBA, SFO, Business Administrator/Board Secretary, and Isabel Machado, Board General Counsel. Regular Meeting Minutes April 23, 20 15 Page 2of311 A motion was made to convene into Executive Session at 6:03 p.m. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

Title Barcode Call Number 101 Dalmatians 31027150427413 DVD-O 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure 31027150151013 D 101 Da

Title Barcode Call Number 101 Dalmatians 31027150427413 DVD-O 101 dalmatians II Patch's London adventure 31027150151013 D 101 dalmatians II Patch's London adventure 31027150427421 DVD-O 20 fairy tales 31027150332779 J DVD T A cat in Paris 31027150324552 JDVD-C A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving 31027150308191 C A Charlie Brown valentine 31027150431993 J DVD C A Cinderella story 31027150508006 J DVD-C A dog's way home 31027150336366 J DVD D A very merry Pooh year 31027100103544 W A wrinkle in time 31027150286017 W Abominable 31027150337182 J DVD A Adventure time The suitor 31027150330112 J DVD A Air Bud seventh inning fetch 31027150146823 A Air buddies 31027150385355 A Aladdin 31027100101845 VC FEATURE Alexander and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day 31027150331177 J DVD A Alice in Wonderland 31027150429179 DVD-A Alice in Wonderland 31027150431175 DVD-A Aliens in the attic 31027150425854 A Alvin and the chipmunks batmunk 31027150508196 J DVD-A Alvin and the chipmunks Chipwrecked 31027150507065 DVDJ-A Alvin and the chipmunks Christmas with the chipmunks 31027150504039 JDVD-C Alvin and the Chipmunks Road chip 31027150332738 J DVD A Alvin and the Chipmunks the squeakquel 31027150333330 J DVD A Anastasia 31027150508345 DVDJ-A Angelina Ballerina All dancers on deck 31027150288492 J DVD A Angelina Ballerina Mousical medleys 31027150327423 J DVD A Angelina ballerina Ultimate dance collection 31027150507214 DVDJ-A Angry birds toons Season one, volume two 31027150330047 J DVD A Angry birds toons Volume 1 31027150329148 J DVD A Annie 31027150385074 JDVD -A Another Cinderella story 31027150325872 J DVD A Arthur stands up to bullying 31027150327506 J DVD ART Atlantis, the lost empire 31027150290738 J DVD A B.O.B.'s big break 31027150333355 J DVD B Baby Looney Tunes Volume 3 Puddle Olympics 31027150386346 B Balto Wings of change 31027150304364 BALTO Barbie in the Nutcracker 31027150388789 B Barbie The Pearl Princess 31027150330088 J DVD B Barney A very merry Christmas 31027150503726 DVD-J Batman & Mr. -

Launching Young Readers Viewers' Guide

Teaching children to read and helping those who struggle Learn More By watching our video series, Reading Rockets: Launching Young Readers. Available in VHS and DVD-ROM formats. Order today at 800-228-4630. Or online at www.gpn.unl.edu. Reading Rockets: Launching Young Readers was produced by WETA, the public TV station in Washington, D.C., and Rubin Tarrant Productions. Launching Young Readers Print Guides You’ll receive a Viewers’ Guide with each videotape or DVD Viewers’ Guide purchase. If you order the entire series, you also get your For parents, educators, day care choice of a Teachers’ Guide or Family Guide. You can also providers, tutors, and anyone else who cares about kids! download all three guides at www.ReadingRockets.org. Funding for Reading Rockets is provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. This guide was created by WETA, which is solely responsible for its content. © 2002, Greater Washington Educational Telecommunications Association, Inc. Distributed by GPN, P.O. Box 80669, Lincoln, NE 68501-0669 800-228-4630 • f/800-306-2330 • [email protected] • www.gpn.unl.edu www.ReadingRockets.org About Reading Rockets About the Series his Viewers’ Guide is a companion to the PBS series eading Rockets: Launching Young Readers is a T Reading Rockets: Launching Young Readers. The R public TV series designed for teachers, parents, care- series is part of Reading Rockets, a multimedia project that givers, and anyone else interested in helping children learn looks at how young kids learn to read, why so many strug- to read. -

West Islip Public Library

CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) - as of January 1, 2013 NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker (CC) NRA Alexander Graham Bell PG Alice in wonderland (2010-Johnny Depp) (SDH) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (CC) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (SDH) (2010 release) PG Aliens in the attic (SDH) NRA All aboard America (CC) NRA All about airplanes and flying machines NRA All about big red fire engines/All about construction NRA All about dinosaurs (CC) NRA All about dinosaurs/All about horses NRA All about earthquakes (CC) NRA All about electricity (CC) NRA All about endangered & extinct animals (CC) NRA All about fish (CC) NRA All about -

June 2010 Chester Littleville

Gateway Regional School District SCHOOL LIBRARY COLLECTION CONTENTS OF AUTHORS ON ELA APPENDIX B SUGGESTED AUTHORS AND ILLUSTRATORS OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LITERATURE AND WORLD LITERATURE Grades PK - 2 Chester Littleville RESOURCES THAT SUPPLEMENT SCHOOL LIBRARY COLLECTIONS ( Author Studies , Poem Hunter , Teachers and Kids of All Ages ) Aliki (informational: All by myself, The many lives of Benjamin All by myself, The many lives of Benjamin science and history) Franklin, A weed is a Flower, Hush Little Franklin, The Gods and Goddesses of Baby, Marianthe's story;We are best friends, Olympus, Fossils tell of long ago, Hello! Welcome, little baby,; The Two of Them Good-bye! My Visit to the Zoo, Mitsumasa Anno Anno’s Mysterious Multiplying Jar;, Anno’s Anno’sMysterious Multiplying Jar, Anno’s (multi-genre) Counting Boo;, Topsy-Turvies; Anno’s Counting Book, Anno’s Journey, Anno’s Magic Seeds ; Alphabet Edward Ardizzone Tim all alone, Johnny the clockmaker, A likely place; Tim and Ginger (multi-genre) Nicholas and the Fast -Moving Diesel; Tim and Ginger Molly Bang (multi- The grey lady and the strawberry snatcher, The grey lady and the strawberry snatcher,; genre) From sea to shining sea : a treasury of…, When Sophie gets angry Paulette Bourgeois The Moon; The sun; Franklin's Christmas Franklin's class trip; Franklin is messy; (multi-genre) gift; Franklin goes to school; Franklin and the Franklin wants a pet; Franklin's Halloween; baby; Police officers; Franklin is messy Franklin has a sleepover; Franklin's blanket; Big Sarah's little boots; -

Where Books Come Alive!

PUBLIC PERFORMANCE DVDS,VIDEOS AND AUDIO BASED ON OUTSTANDING CHILDREN’S BOOKS Where Books Come Alive! Table of Contents Where Books Come Alive! Fall 2008 New Releases page 4-5 Spring 2008 New Releases page 6-7 For more than 50 years, Weston Woods’ The Playaway® Audio Collection page 8-9 mission has been to motivate children to want New and Noteworthy page 10 to read. Every book is brought to life through Story Hour Collection page 11-41 engaging visuals and stirring word-for-word Alphabetical Listing narrations. They are accompanied by an SPECIAL COLLECTIONS History page 42-43 original musical score, composed to perfectly Author Documentaries page 44 fit the mood and nuances of each story. Caldecott/Newbery page 45 All of our new DVD titles have added bonus features to Foreign Language page 46-47 further enhance the experience of seeing your favorite Rabbit Ears® page 48 Scholastic Entertainment page 49 books brought to life. These features include: Scholastic Audio page 50-55 ★Read-Along allows children to follow WESTON WOODS’STORY COLLECTIONS ON DVD each word as it is simultaneously Read- Thematic DVD page 68-70 narrated and highlighted on the Along! Story Collections screen, strengthening vocabulary, Spanish Bilingual DVD page 70 comprehension and fluency. All new DVDs now offer Story Collections three viewing options: Read-Along, closed-captioned Favorite Author DVD page 71 Story Collections subtitles or no text at all. ★Closed-captioned subtitles and/or subtitled captions - INDEXES Thematic Index page 56-57 Closed–captioned subtitles include Month-by-Month Index page 58-59 descriptive text for the hearing Critic’s Choice – Best Titles page 60 impaired, while subtitled captions from Other Producers contain only the spoken Alphabetical Index of page 61-67 narration and character Weston Woods’ Titles dialogue (without descriptive text) for use as a reading EXPANDED PURCHASING OPTIONS AVAILABLE! tool. -

Choices Child Care Resource and Referral

Categories AT= Assistive Technology IT= Infant and Toddler VAP= Van Active Play VART= Van Art VB= Van Books VB (R)= Van Book Resource VBL= Van Blocks VC= Van Cassette VCD= Van CD VDP=Van Dramatic Play VE= Van Educational VG= Van Game VL= Van Literacy VMTH= Van Math VMUS= Van Music VS= Van Software VSC= Van Science VSEN= Van Sensory VTT= Van Table Toys VV= Van Video AT= Assistive Technology Item # Description Details AT - 1 Voice Pal Max 1 Count AT - 2 Traction Pads Set 0f 5 AT - 3 Free Switch 1 Count AT - 4 Battery Interrupters ½” (AA) AT - 5 Handy Board 1 Count AT - 6 Chipper 1 Count AT - 7 Sequencer 1 Count AT - 8 Magic Arm Knob AT - 9 Mounting Plates for Magic Arm LRMP,LIMP, SRMP,STMP,SCMP AT - 10 Dual Lock (2’ per center) AT- 11 Free Hand Starter Kit 1 Count AT - 12 Overlay Packets 1 Count AT - 13 Battery Interrupters ¾” (C/D) AT - 14 Pal Pads Small, Medium, Large AT - 15 Flexible Switch Large AT - 16 Picture Board 1 Count AT - 17 Sensory Software All Versions AT - 18 Tech Speak 6 x 32 AT - 19 Tech Talk 8 x 8 AT - 20 Stages 1 Count AT - 21 Four Frame Talker 1 Count AT - 22 Qwerty Color Big Keys Plus Keyboard AT - 23 Rag Dolls Set of Eight AT - 24 Adaptive Equipment Complete Set AT - 25 Chirping Easter Egg 1 Count AT - 26 Eye Gaze Board Opticommunicator AT - 27 PCA Checklist 1 Count AT - 28 BIGMack Communication Aid Green AT - 29 Powerlink 3 1 Count AT - 30 Spec Switch Blue AT - 31 Step by Step Communicator w/o Levels Red AT - 32 Easy Ball 6 44.95, 269.70 AT - 33 Old McDonalds Farm Deluxe 1 Count AT - 34 Monkeys Jumping on a Bed 1 -

FTI 2009 CD DVD Consumer Price List

CHILDREN'S CD and DVD ENTERTAINMENT [email protected] Canadian wholesale price list January 2009 www.firetheimagination.ca code description retail AL SIMMONS MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 801464200629 AL SIMMONS: CELERY STALKS AT MIDNIGHT - CD $10.95 801464200520 AL SIMMONS: SOMETHING FISHY - CD $10.95 ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS (DVDs also available) MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 793018298629 ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS SOUNDTRACK (2007) - CD $26.95 076744008824 CHIPMUNKS ADVENTURE - CD $15.95 5099921310225 CHIPMUNKS SING THE BEATLES - CD $12.95 ALY AND AJ MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 720616264220 ALY AND AJ: INSOMNIATIC - CD $22.95 720616264022 ALY AND AJ: INTO THE RUSH (Deluxe Edition) - CD with DVD $23.95 720616250520 ALY AND AJ: INTO THE RUSH - CD $22.95 ANNE MURRAY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 724353548520 ANNE MURRAY: THERE'S A HIPPO IN MY TUB - CD $16.95 ANN RACHLIN - GREAT COMPOSERS SPOKEN WORD 9781902680088 ANN RACHLIN: HAPPY BIRTHDAY, MR. BEETHOVEN: THE LIFE OF BEETHOVEN - CD $19.95 9781902680095 ANN RACHLIN: MOZART THE MIRACLE MAESTRO: THE LIFE OF MOZART - CD $19.95 9781902680125 ANN RACHLIN: MR. HANDEL'S FIREWORKS PARTY: THE LIFE OF HANDEL - CD $19.95 9781902680101 ANN RACHLIN: ONCE UPON THE THAMES: THE LIFE OF HANDEL - CD $19.95 9781902680118 ANN RACHLIN: PAPA HAYDN'S SURPRISE: THE LIFE OF HAYDN - CD $19.95 ANN RACHLIN - RUSSIAN BALLETS SPOKEN WORD 9781902680163 ANN RACHLIN: CINDERELLA: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680187 ANN RACHLIN: FIREBIRD, THE: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680149 ANN RACHLIN: NUTCRACKER: THE STORY OF THE -

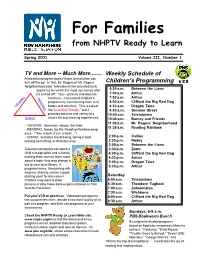

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn Spring 2001 Volume III, Number 1 TV and More -- Much More........ Weekly Schedule of A television program doesn’t have to end when you turn off the set. In fact, Mr. Rogers of Mr. Rogers Children’s Programming Neighborhood said, “television is the only electronic appliance for which the most use comes after 6:30 a.m. Between the Lions it’s turned off.” You -- parents and daycare 7:00 a.m. Arthur READING teachers -- can extend children’s 7:30 a.m. Arthur programs by connnecting them with 8:00 a.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog VIEWING books and activities. This is called 8:30 a.m. Dragon Tales the “Learning Triangle,” and it 9:00 a.m. Sesame Street provides balance and variety to a 10:00 a.m. Teletubbies DOING child’s life and learning experiences. 10:30 a.m. Barney and Friends 11:00 a.m. Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood • VIEWING: television, videos, the Web. 11:30 a.m. Reading Rainbow • READING: books (as the Reading Rainbow song says: “Take a look, it’s in a book...”). • DOING: activities like drawing, taking a walk, 2:00 p.m. Caillou making something, or dramatic play. 2:30 p.m. Noddy 3:00 p.m. Between the Lions Television programs can spark a 3:30 p.m. Zoom child’s imagination and curiosity, 4:00 p.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog making them want to learn more 4:30 p.m. Arthur about a topic--this may prompt a 5:00 p.m. -

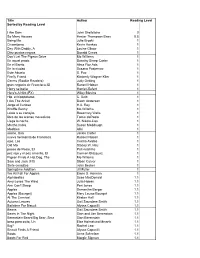

Reading Counts

Title Author Reading Level Sorted by Reading Level I Am Sam John Shefelbine 0 So Many Houses Hester Thompson Bass 0.5 Being Me Julie Broski 1 Crisantemo Kevin Henkes 1 Day With Daddy, A Louise Gikow 1 Diez puntos negros Donald Crews 1 Don't Let The Pigeon Drive Mo Willems 1 En aquel prado Dorothy Sharp Carter 1 En el Barrio Alma Flor Ada 1 En la ciudad Susana Pasternac 1 Este Abuelo S. Paz 1 Firefly Friend Kimberly Wagner Klier 1 Germs (Rookie Readers) Judy Oetting 1 gran negocio de Francisca, El Russell Hoban 1 Harry se baña Harriet Ziefert 1 Here's A Hint (FX) Wiley Blevins 1 Hip, el hipopótamo C. Dzib 1 I Am The Artist! Dawn Anderson 1 Jorge el Curioso H.A. Rey 1 Knuffle Bunny Mo Willems 1 Léale a su conejito Rosemary Wells 1 libro de las arenas movedizas Tomie dePaola 1 Llega la noche W. Nikola-Lisa 1 Martha habla Susan Meddaugh 1 Modales Aliki 1 noche, Una Jackie Carter 1 nueva hermanita de Francisca Russell Hoban 1 ojos, Los Cecilia Avalos 1 Old Mo Stacey W. Hsu 1 paseo de Rosie, El Pat Hutchins 1 pez rojo y el pez amarillo, El Carmen Blázquez 1 Pigeon Finds A Hot Dog, The Mo Willems 1 Sam and Jack (FX) Sloan Culver 1 Siete conejitos John Becker 1 Springtime Addition Jill Fuller 1 We All Fall For Apples Emmi S. Herman 1 Alphabatics Suse MacDonald 1.1 Amy Loves The Wind Julia Hoban 1.1 Ann Can't Sleep Peri Jones 1.1 Apples Samantha Berger 1.1 Apples (Bourget) Mary Louise Bourget 1.1 At The Carnival Kirsten Hall 1.1 Autumn Leaves Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bathtime For Biscuit Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Beans Gail Saunders-Smith 1.1 Bears In The Night Stan and Jan Berenstain 1.1 Berenstain Bears/Big Bear, Sma Stan Berenstain 1.1 beso para osito, Un Else Holmelund Minarik 1.1 Big? Rachel Lear 1.1 Biscuit Finds A Friend Alyssa Capucilli 1.1 Boots Anne Schreiber 1.1 Boots For Red Margie Sigman 1.1 Box, The Constance Andrea Keremes 1.1 Brian Wildsmith's ABC Brian Wildsmith 1.1 Brown Rabbit's Shape Book Alan Baker 1.1 Bubble Trouble Mary Packard 1.1 Bubble Trouble (Rookie Reader) Joy N.