S Lsymmetry CONCEPTS MODERN PHYSIC~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proseminar Theoretical Physics PHY391

Proseminar Theoretical Physics PHY391 Massimiliano Grazzini University of Zurich FS21, February 22, 2021 Introduction A selection of topics in theoretical physics relevant for high-energy and condensed matter physics Each student is supposed to give one presentation and to attend at least 80% of the presentations by the other students Active participation is required Assistants: Luca Buonocore Bastien Lapierre Chiara Savoini Ben Stefanek Luca Rottoli 1) Lorentz and Poincare groups Quantum mechanics is an intrinsically nonrelativistic theory. A change of viewpoint — moving from wave equations to quantum field theory — is necessary in order to make it consistent with special relativity. For this reason, it is therefore paramount to understand how Lorentz symmetry is realised in a quantum setting. Besides invariance under Lorentz transformation, invariance under space-time translations is another necessary requirement in the construction of quantum field theory. Translations plus Lorentz transformation form the inhomogeneous Lorentz group, or the Poincaré group. The study of the Poincaré group and its representation allows one to understand how the concept of particle emerges. References: M. Maggiore, A Modern Introduction to Quantum Field Theory, Ch. 2. Luca R 2) Noether theorem You have already seen that in physics we have a deep relation between symmetries and conserved quantities (translation invariance -> momentum conservation; space isotropy -> angular momentum conservation…) The Noether theorem states that every continuous symmetry of the action functional leads to a conservation law derivation of the theorem starting from a classical field Lagrangian (Goldstein chap. 12.7) application of the theorem in the case of invariance under translations and Lorentz transformations: energy-momentum and angular momentum conservation (Itzykson-Zuber chap. -

International Centre for Theoretical Physics

IC/79M INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS NON-LEPTONIC RADIATIVE DECAYS OF HYPERONS IN A GAUGE-INVARIANT THEORY Riazuddin and Fayyazuddln INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION 1979 MIRAMARE-TRIESTE IC/T9M I. INTRODUCTION l) 2l It has recently been shown ' that the contributions from the quark- International Atomic Energy Agency quark scattering processes s+ u •* u + d through the W~ exchange and and s + d ~* q + q through a gluon exchange (yhere one gluon vertex, s -t d + g, is United Nations Educational Scientific and Culturaa Organization weak, while the other, q. + q + g, is strong) to the effective non-leptonic INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS Hamiltonian give a good description of non-leptonic decays of hyperons and ff. Such contributions involve four quark operators and for the purpose of calculating the matrix elements ^B |H*IC1B )> . the non-relativistic quark model together with SU(6) wave functions for baryons are used; the low- lying baryona Br are regarded as an a-wave three-quark system. In this T limit <^BaJH*' '|Br y =i 0. The purpose of this paper is to extend the above considerations to non-leptonic radiative decays of hyperona. The effective HOH-LEPTOBIC RADIATIVE DECAYS OF HYPEROKS IB A GAUGE-INVARIANT THEORY • parity-violating Hamiltonian for such decays is obtained in a gauge-invariant way from the corresponding Hamiltonian for ordinary non-leptonic decays, vhile Riozuddln • the parity-conserving radiative decoys are simply given by baryon poles. As International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy, we shall see,it is possible to get a satisfactory description of non-leptonic radiative decays of hyperons in the above picture. -

Long-Distance Contribution to the Muon-Polarization Asymmetry in K¿\¿Μ¿Μà

PHYSICAL REVIEW D, VOLUME 65, 076001 Long-distance contribution to the muon-polarization asymmetry in K¿\¿µ¿µÀ Giancarlo D’Ambrosio* and Dao-Neng Gao† Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Napoli, Dipartimento di Scienze Fisiche, Universita` di Napoli, I-80126 Naples, Italy ͑Received 9 November 2001; published 28 February 2002͒ ⌬ We reexamine the calculation of the long-distance contribution to the muon-polarization asymmetry LR , which arises, in Kϩ!ϩϩϪ, from the two-photon intermediate state. The parity-violating amplitude of this process, induced by the local anomalous KϩϪ␥*␥* transition, is analyzed; unfortunately, one cannot expect to predict its contribution to the asymmetry by using chiral perturbation theory alone. Here we evaluate ⌬ this amplitude and its contribution to LR by employing a phenomenological model called the FMV model ͑factorization model with vector couplings͒, in which the use of the vector and axial-vector resonance ex- change is important to soften the ultraviolet behavior of the transition. We find that the long-distance contri- bution is of the same order of magnitude as the standard model short-distance contribution. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.65.076001 PACS number͑s͒: 11.30.Er, 12.39.Fe I. INTRODUCTION ͉⌫ Ϫ⌫ ͉ ⌬ ϭ R L ͑ ͒ LR ⌫ ϩ⌫ , 3 The measurement of the muon polarization asymmetry in R L ϩ!ϩϩϪ the decay K is expected to give some valuable ⌫ ⌫ where R and L are the rates to produce right- and left- information on the structure of the weak interactions and ϩ flavor mixing angles ͓1–6͔. -

The Man Who Designed Pakistan's Nukes Just Died

The Man Who Designed Pakistan’s Nukes Just Died – And No One Noticed by Pervez Hoodbhoy Riazuddin 10 November 1930 – 9 September 2013 When Riazuddin—that was his full name—died in September at age 82 in Islamabad , international science organizations extolled his contributions to high- energy physics. But in Pakistan, his passing was little noticed. except for a few newspaper lines and a small reference held a month later at Quaid-e-Azam University, where he had taught for decades. In fact, very few Pakistanis have heard of the self-effacing and modest scientist who drove the early design and development of Pakistan’s nuclear program. Riazuddin never laid any claim to fathering the bomb—a job that requires the efforts of many—and after setting the nuclear ball rolling, he stepped aside. But without his theoretical work, Pakistan’s much celebrated bomb makers, who knew little of the sophisticated physics critically needed to understand a fission explosion, would have been shooting in the dark. A bomb maker and peacenik, conformist and rebel, quiet but firm, religious yet liberal, Riazuddin was one of a kind.. Mentored by Dr. Abdus Salam, his seminal role in designing the bomb is known to none except a select few. Spurred by Salam Born in Ludhiana in 1930 the twin brothers, Riazuddin and Fayyazuddin, were often mistaken for each other. Like other lower middle class Muslim children living in a religiously divided community, they attended the Islamia High School run by the Anjuman-i-Islamia philanthropy. The school had no notable alumni, and was similar to the town’s single public and two Hindu-run schools. -

Historical Variations in the Specialized Subjects of the Elected Fellows of the Pakistan Academy of Sciences

Historical Variations in the Specialized Subjects of the Elected Fellows 251 Proceedings of the Pakistan Academy of Sciences, 48 (4): 251-260 (2011) Pakistan Academy of Sciences Copyright © Pakistan Academy of Sciences ISSN: 0377 - 2969 Review Article Historical Variations in the Specialized Subjects of the Elected Fellows of the Pakistan Academy of Sciences Shafiq Ahmad Khan1 and M.M. Qurashi2 1 4-A, PCSIR, ECHS, Phase-1, Canal Bank Road, Lahore 2 Pakistan Association for History & Philosophy of Sciences, c/o Pakistan Academy of Sciences, Sector G-5/2, Constitution Avenue, Islamabad Abstract: The Pakistan Academy of Sciences (PAS) was inaugurated on 16th February 1953 by the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, Khawaja Nazim-ud-Din. The Academy is a non-governmental and non-political supreme body of distinguished scientists, to which the Government has entrusted the consultative and advisory status. The affairs of the Academy are regulated by its Charter and the Bye- Laws approved by its Fellows who are elected through the prescribed procedure. Since its establishment, the Academy has elected 162 scientists belonging to all branches of science as its Fellows during a period of 58 years (i.e., 1953-2010) at an average of 2.8 Fellows per year. However, no Fellows were elected for 10 years (i.e., 1955, 1960, 1962, 1963, 1965, 1969, 1975, 1981, 1985 and 1987) and, therefore, the average induction-rate works out to be about 3.5 Fellows per year during a period of 48 years. A comparison of the number of Fellows elected per decade during 50 years (i.e.,1961-2010) in physical and bio-sciences is provided and depicted graphically, showing the variation trend regarding the specialized fields of the elected Fellows for the studied five decades. -

Revized Voter's List for PPS Election 2014 Membership Title Name of Member Position Postal Address No

Revized Voter's List for PPS Election 2014 Membership Title Name of Member Position Postal Address No 1 Dr G Murtaza Professor Salam Chair in PhysicsG. C. University, Lahore 2 Dr Asghari Maqsood Professor NUST, Rawalpindi Associate Department of Physics,Quaid-i-Azam University, 3 Dr Imrana Ashraf Professor Islamabad 4 Mr Farid A. Khawaja Professor Islamabad 5 Dr A. H. Nayyar Professor Sustainable Development Institute of Pakistan Department of Physics, Quaid-i-Azam University, 6 Dr M Zakaullah Professor Islamabad. 7 Dr M. Aslam Baig Professor Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad 8 Dr Sajjad Mamood Professor USA 9 Dr Kamaluddin Ahmed Professor House 178, Street 18, F-10/2, Islamabad Associate 10 Dr Muhammad Iqbal University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore Professor Associate 11 Dr Khalid Khan Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad Professor 12 Dr Samina S. Masood USA C/o National Centre of Physics at Quaid-i-Azam 13 Dr Fayyazuddin Professor University, Islamabad 14 Dr Riazuddin Professor Deceased Department of Physics, Quaid-i-Azam University, 15 Dr Arshad M. Mirza Professor Islamabad Department of Physics, Quaid-i-Azam University, 16 Dr S. K. Hasanain Professor Islamabad Centre for Advanced Mathematics & Physics, 17 Dr Asghar Qadir Professor National University of Sciences & Technology 18 Dr A. J. Hamdani Professor H. No. 522, St. 46, G-10/4, Islamabad Air University, PAF Complex Sector E-9, 19 Dr Abdullah Sadiq Professor Islamabad 20 Dr M. Anwar Professor Ex. C.S.O. PAEC H# 51, St #62, F- 10/3 Islamabad 21 Dr Khalid Rashid Scientist 473-B, St. 10, F-10/2, Islamabad. -

Prof. Riazuddin

Obituary – Prof. Riazuddin Adnan Bashir Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico Prof. Riazuddin, an eminent Pakistani scientist, passed away on September 30, 2013. He was born in 1930 in Ludhiana, located in Indian Punjab, in a lower middle class family. During the traumatic experience of Indo-Pak partition which saw the largest mass migration in human history involving nearly 10 million people, his family moved to Pakistan and in the process they lost all their material possession. Instead of mourning the lost past, he decided to pursue fresh dreams in his new homeland Pakistan, with the hope of a better future for himself and his fellow countrymen. He received his college level education in Pakistani Punjab in the city of Lahore which was considered as a heart of India even before partition, central to the country’s artistic, cultural, literary and political life for centuries. Despite his outstanding performance in pre-university exams, Prof. Riazuddin did not pursue a career in engineering which was the usual choice of the majority of talented young students of his time. Instead, he joined the Government College, Lahore, to study for his first degree in physics and mathematics. He also obtained masters degree from the same institution. Though the Government College was always renowned primarily for its excellence in the teaching of English language and literature, Prof. Riazuddin´s studentship at the Government College coincided with the brief return of the famous Pakistani Nobel laureate Prof. Abdus Salam. Although Prof. Salam himself had a hard time adjusting to the harsh realities of life in Pakistan, his presence, teaching and enthusiasm for physics provided an ideal platform for Prof. -

Long-Distance Contribution to the Muon-Polarization Asymmetry in K+ → Π+Μ+Μ

INFNNA-IV-2001/24 DSFNA-IV-2001/24 CERN-TH/2001-312 November 2001 Long-distance contribution to the muon-polarization + + + asymmetry in K π µ µ−∗ → Giancarlo D’Ambrosio† and Dao-Neng Gao‡ Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Napoli, Dipartimento di Scienze Fisiche, Universit`a di Napoli, I-80126 Naples, Italy Abstract We revisit the calculation of the long-distance contribution to the muon-polarization + + + asymmetry ∆LR,whicharises,inK π µ µ−, from the two-photon intermediate state. The parity-violating amplitude of→ this process, induced by the local anomalous + K π−γ∗γ∗ transition, is analysed; unfortunately, one cannot expect to predict its con- tribution to the asymmetry by using chiral perturbation theory alone. Here we evaluate this amplitude and its contribution to ∆LR by employing a phenomenological model called the FMV model, in which the utility of the vector and axial-vector resonances exchange is important to soften the ultraviolet behaviour of the transition. We find that the long-distance contribution is of the same order of magnitude as the standard model short-distance contribution. † E-mail: Giancarlo.D’[email protected], and on leave of absence at Theory Division, CERN, CH-1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland. ‡ E-mail: [email protected], and on leave from the Department of Astronomy and Applied Physics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, China. * Work supported in part by TMR, EC–Contract No. ERBFMRX-CT980169 (EURODAΦNE). 1 Introduction + + + The measurement of the muon polarization asymmetry in the decay K π µ µ− is expected to give some valuable information on the structure of the weak interactions→ and flavour mixing angles [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. -

The Quark Model and SU(3)

The Quark Model and SU(3) Peyton Rose 10 June 2013 Physics 251 Scattering Experiments at SLAC in the 1960s suggested that pointlike particles exist in the proton Atom + - - - + + + - - + Pre-Experiment Post-Experiment Proton uuu ddd uuu Six quarks and six anti-quarks have been discovered An additional quantum number – color – restricts combinations of quarks. In nature, we observe qq and qqq q (q) q q The free quark Lagrangian density has a SU(n) symmetry for n quarks* * with identical masses First, let's consider a model with only up and down quarks. In this case, the relevant quantum number is isospin with an SU(2) symmetry. Generators of the 2-dimensional representation of SU(2): Commutation Relations: Raising/Lowering Operators There are two eigenstates of s3 In the 2 representation, u corresponds to and d corresponds to In the 2* representation,-d corresponds to and u corresponds to Meson states are formed from 2 2* 2 2* = 3 1 → We expect 4 meson states With appropriate linear combinations and normalization, we recover the pions ... ...which fit into a 3-dim representation of SU(2) In the quark model, we consider three quarks – up, down, and strange There are 8 matrices in the defining representation of SU(3) Two of these matrices are diagonal SU(3) contains pieces of SU(2) Y I U V We can form raising and lowering operators within each subgroup Using the eigenvalues of and , we can draw weight diagrams 3 3* Meson states are 3 3* 3 3* 1 8 = → We expect 9 states! To find states, overlay 3* on 3 in the weight diagram States on the hexagon -

Of Children and Women in Pakistan

United Nations Children’s Fund 90 Margalla Road, Sector: F8/2 Government of Pakistan SITUATION Islamabad, Pakistan [email protected] ANALYSIS www.unicef.org of children and women in Pakistan @United Nations Children Fund’s (UNICEF) June 2012 National Report June 2012 - Pakistan SITUATION ANALYSIS of children and women in Pakistan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Preparation of this Situation Analysis (SitAn) has been a cooperative and consultative effort, involving many players and carried out over a nine-month gestation period. The impetus for the SitAn project came from the UNICEF Country Office, Islamabad, with the full support and encouragement of the Representative, Mr. Dan Rohrmann, throughout the process. The engagement of the Government of Pakistan, and the Governments of Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa/ Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Gilgit Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir, through their participa- tion in the SitAn Steering Committee and in the consultations held at regional level, has been critical to the completion of this project. Special tribute must be paid to Dr. Saba Gul Khattak, member, Social Sector, Planning Commission, for her leadership and active participation in the process as Chairperson of the SitAn Steering Committee. Within UNICEF, active day-to-day supervision of the project was provided by Khamhoung Keovilay and Ehsan Ul Haq, without whose guidance and support its completion would not have been possible. Support, advice and assistance were provided by UNICEF staff in Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi, Quetta -

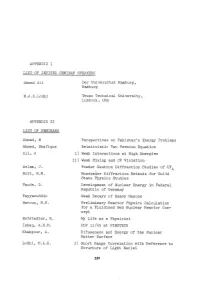

APPENDIX I LIST of INVITED SEMINAR SPEAKERS Ahmad Ali

APPENDIX I LIST OF INVITED SEMINAR SPEAKERS Ahmad Ali Der Universitat Hamburg, Hamburg M.A.K.Lodhi Texas Technical University,. Lubbock, USA APPENDIX II LIST OF SEMINARS Ahmad, M Perspectives on Pakistan's Energy Problems Ahmed, Shafique Relativistic Two Fermion Equation Ali, A i) Weak Interactions at High Energies ii) Weak Hixing and CP Violation Aslam, J. Powder Neutron Diffraction Studies of UF4 Butt, N.M. Mossbauer Diffraction Hethods for Solid State Physics Studies Faude, D. Development of Nuclear Energy in Federal Republic of Germany Fayyazuddin Weak Decays of Heavy I1esons Haroon, M.R. Preliminary Reactor Physics Calculation for a Fluidised Bed Nuclear Reactor Con cept Hofstadter, R. My Life as a Physicist Ishaq, A.H.B. PDP 11/45 at PINSTECH Khakpour, A. Difuseness and Energy of the Nuclear Matter Surface Lodhi, H.A.K. i) Short Range Correlation with Reference to Structure of Light Nuclei 559 560 APPENDIX ii) Fission and Al~ha Decay Anomalies with reference to Superheavy Elements Magd, A.Y.Abdul i) Interaction of Relativistic Particles with Nuclei ii) Angular ~Iomentum Coherence in Heavy Ion Reactions Mahmud, Bashiruddin Problems of Energy with Respect to Trans fer of Technology in Developing Countries Malik, G.M. Computing Facilities at Engineering Uni versity, Lahore Moravcsik, H.J. i) Energy Supylies and Space Colonization ii) An Overview of Quantum Hechanical Few Body Problems Murray, R.L. Nuclear Proliferation and Safeguards J'.Tayyar, A.H. Solition Propagation in l1agnetic Transi tions Panchapakesan, N. i) Particle Creation in a De Sitter Universe ii) Changing Superconducting Transition Tempe ratures in Haterials Paul, w. -

LIST of SEMINARS Bhatti, Naseem Bhutta, S.M. Burton, L. Cirit, M

APPENDIX I LIST OF SEMINARS Bhatti, Naseem Computerised Information Services from INIS Magnetic 'rapes at PINS TECH Bhutta, S.M. Application of Quality Assurance Programmes in Improving the Performance of Energy Projects Burton, L. Solar Cell Technology Cirit, M. Quark Model of Low PT Particle Production Everitt, C.W.F. Death of Maxwell and Birth of Einstein Fayyazuddin A Gauge Model for Strong and Electro-Weak Interactions Frydman, R.J. The Law of Free Fall Myth and Historic Reality Ida, Aziz A. Problems of Nuclear Power Programme Imple mentation in a Developing Country Ilyas, M.M. Potential Models for Charmonium Izharul Hag, A.M. Energy Planning in Pakistan Suwabara, S. Poiseulle Turbulance Leistikow, S.O. i) Basic Aspects of High Temperature Oxidation (Materials, Binary and Tertiary Alloys) ii) Experimental Work on Oxidation Kinetics on Zircoly-IV under PWR Safety Aspects Leschiutta, S. i) History of Time Measurement for 2000 B.C. to 1500 A.D. ii) Time Synchronization by Radio Mahmood, Sajjad Mass Spectrum of Charmonium Majid, C.A. Electronic Conduction in Amorphous Solids of the Systems As-Ti-Se 575 576 SEMINARS Mamoon, A.M. Current Trends in Solar Energy Research in Saudi Arabia Mirza, Ishaq Remote Sensing Physics and Satellite Appli cations Niedermeyr, W. Principles of Computerised Information Retrieval Poole, P.C. Computer Operating System Qazi, A.Q. Wind Energy Systems Ramamurthy, V. S . Results of Search for Superheavy Elements in Indian Monazite Sardelis, D.A. The Law of Free Fall, Myth and Historic Reality Smith, K.R. Three Mile Nuclear Power Reactor Accident Soni, V. Topological Structure in Helium 3 Wettrich, C.