Valuing Waste in Dumpster Diving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dumpster Diving and the Ethical Blindspot of Trade Secret Law

Dumpster Diving and the Ethical Blindspot of Trade Secret Law Harry Wingo "The maintenance of standardsof commercial ethics and the encouragement of invention are the broadly statedpolicies behind trade secret law. 'The necessity of good faith and honest, fair dealing, is the very life and spirit of the commercial world. '" "The trilogy of public policies underlying trade secret laws are now: (1) the maintenance of commercial morality; (2) the encouragement of invention and innovation; and (3) the protection of the fundamental right of privacy of the trade secret owner. ' Trade secret law is complex and still emerging,3 but throughout its t B.S. U.S. Naval Academy 1984, J.D. Candidate, 1998, Yale Law School. The author wishes to thank Professor Carol Rose, Judge John F. Fader H, and Doug Lichtman for the advice, as well as Lt. Hope Katcharian for her patient support and inspiration. 1. Kewanee Oil v. Bicron, 416 U.S. 470, 481-82 (1974) (quoting National Tube Co. v. Eastern Tube Co., 3 Ohio C.C. (n.s.) 459, 462 (1902). 2. 1 MELVIN F. JAGER, TRADE SECRETS LAW § 1.05, at 1-15 (1997). The Restatement (Third) of Unfair Competition recognizes Mr. Jager as a trade secret law authority. RESTATEMENT (THIRD)OF UNFAIR COMPETITION § 39 reporter's notes at 438 ("The principal treatises on the law of trade secrets are M. Jager, Trade Secrets Law and R. Milgrim, Milgrim on Trade Secrets."). 3. This complexity and flux is underscored by the fact that a simple definition of trade secret remains elusive. Q. American Wheel & Eng'g Co. -

Place in Trash

E8 May 2017 BURRTEC NEWS Waste and Recycling Newsletter Sponsored by the City of San Bernardino and Burrtec Waste Industries for the San Bernardino Commercial Community Recycling Programs —Let Us Help! California Assembly Bill 341 mandates businesses and public entities, generating four (4) cubic yards of trash or more and multi-family residential dwellings with five or more units, to establish and maintain recycling service. Recycling not only conserves our natural resources but can save money by reducing waste disposal costs. Our staff can assist in selecting the appropriate recycling service level, along with the necessary education and outreach to residents and managerial staff. Call our customer service department today to schedule a complimentary waste and recycling assessment. If you already have a recycling program and would like to make additional enhancements, please call our customer service department for assistance. Maintain Your Trash Enclosure Follow these simple tips to keep your trash enclosure clean: • Keep dumpster lids closed. This prevents the rain water from entering the container and keeps wind and feral animals from tossing litter into the parking lot and surrounding areas. • Pick up litter in and around trash enclosure and parking lot. Don’t let it enter the streets or storm drain system. Call Burrtec to empty the dumpster if it is full. • Don’t fill dumpster or compactor with liquid waste or hose it out. Keeping liquids out of your trash and recycling containers will prevent any liquids from leaking into the surrounding area. • Sweep outside areas instead of using a hose. Sweeping not only conserves water, it also prevents the material from entering the storm drain. -

Dumpster Dive Recyclemania Activity

Dumpster Dive RecycleMania Activity Effort & Resources Involved. Requires advance plan- Moderate. Safety gear, thank you ning, administrative approval, and gift for volunteers (i.e. pizza, gift Objective/Overviewdedicated volunteers. certificates). Objective & Overview Use this activity to encourage students to recycle by demonstrating the volume of recyclable materials that go to waste by being thrown in the trash. Volunteers will sort waste into bins or piles. As the piles Stepgrow, the 1: goal Gather is to show students and thatPrepare every time Materialsthey toss “just one” can, bottle, or mobile device into the trash, it adds up to a lot of wasted recyclables. Step 1: Planning and Permission Before you begin planning this activity, get permission from your student activities or waste management office to sort waste from your cafeteria or student union. Choose an outdoor area or another place with lots of passers-by. Check in advance if you need to have a facilities or campus security representative present at the event location. Step 2: Gather Materials Caution tape or rope to designate waste sorting area Protective suits for volunteers (can buy a disposable one for $5 at pksafety.com) Posters advertising your event and explanatory signs to post near the site (pages 3-4) Tables or clear plastic bags to emphasize recyclables that went into the trash Large tarps to protect the ground from waste Step 3: Promote and Prepare Promote the event in advance with flyers around campus (see sample on page 3). Make it fun by listing who will be “dumpster diving,” and consider adding your campus logo. -

Coyne-Dissertation Final Deposit

This Project Can be Upcycled Where Facilities are Available: An Adventure Through Toronto’s Food/Waste Scape Michelle Coyne A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO December 2013 © Michelle Coyne, 2013 Abstract At the intersection of food, regulations, and subjective experiences is a new way of understanding the intersection of wasted food—a new category of edibility. This project investigates the reasons for, and impacts of, politically-motivated dumpster diving and food reclamation activism in Toronto, Canada. The research incorporates ethnographic participant- observation and interviews with politically-motivated dumpster divers in Toronto, as well as that city’s chapter of Food Not Bombs. The project primarily asks how so much quality food/waste is thrown away and becomes, at times, available to be recovered, reworked, and eaten. My research constitutes a living critique of the hybrid experience of food and waste where the divisions between the two categories are not found in locations (the grocery store or dumpster), but rather in the circulations of actions and meanings that dumpster divers themselves re-invest in discarded edible food products. My research objectives are: (1) to document the experience of dumpster divers in Toronto as connected to a broader movement of food/waste activism around the world; (2) to connect this activism to discussions of food safety and food regulations as structuring factors ensuring that edible food is frequently thrown away; (3) to contextualize contemporary food/waste activism within a history of gleaning, and in relation to enclosure acts that have left Canada with no legal protections for gleaners nor recognition of the mutually beneficial social relation between gleaners and farmers; (4) to explore dumpster divers’ work as part of the circulation of urban culture within media networks. -

Booklet and Pamphlet Template

ªCollectivism, whether it be communist, fascist or capitalist ideologically isn't something that serves my interests as an indigenous subsistence farmer and forager living in these remote mountains. Whatever industrial dogma I'm ordered to live my life by only serves to fill my heart with sorrow. I will loudly reject the idea of a collective society at every opportunity, regardless of its ideological alliance. All industry kills all life. Fuck Your I'm an anarchist. Even the idea of a ªsocietyº governing my way of life makes me vomit a Red Revolution: little. Your needs aren't my needs, I don't want to go where the collective wants to take me... Against Ecocide, ...I want to be liberated from the system, not become the system. The collective isn't my Towards Anarchy master. The collective is really just another by Ziq state, however nicely you package it.º Warzone Distro WARZONEDISTRO.NOBLOGS.ORG 2019 Let Go Of Your Tedious Slogans “There’s no ethical consumption under capitalism” is a tired meme that I wish would die. So often this slogan is used by reds to pooh-pooh those of us that strive to make life choices that aid harm-reduction in our communities and our natural environments. Vegan diets, bicycling, dumpster diving, upcycling, guerilla gardening, permaculture, squatting, illegalism, food forestry, communes, self- sufficiency, and all the other “lifestylist” pursuits “individualist” anarchists undertake to minimize their harm on the environment are shamed and mocked by many anarcho-communists, social-ecologists, anarcho- transhumanists, syndicalists and other industry-upholding anarchists. These reds are well-versed in workerist rhetoric, and see all lifestyle choices as “a distraction” from the global proletarian revolution they see as their singular goal. -

Food Movements in Germany: Slow Food, Food Sharing, and Dumpster Diving

International Food and Agribusiness Management Review Volume 18 Issue 3, 2015 Food Movements in Germany: Slow Food, Food Sharing, and Dumpster Diving a b Meike Rombach and Vera Bitsch a Research Associate, Chair Group Economics of Horticulture and Landscaping, Technische Universität München, Alte Akademie 16, 85354 Freising, Germany b Professor, Chair of Economics of Horticulture and Landscaping, Technische Universität München, Alte Akademie 16, 85354 Freising, Germany Abstract The study investigates the motivation to participate in food movements, as well as the activities and knowledge regarding food waste of active food movement members in Germany. The study builds on theories of social movements. A total of 25 in-depth interviews with activists of the Slow Food organization, the Food Sharing organization, and with dumpster divers were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed through qualitative content analysis. Participation in the movements rests upon instrumental, ideological, and identificational motivations. The knowledge of food waste differs between the three movements. Sharing, food waste, and tendencies of anti-consumerism play a strong role in all movements. Keywords: activism, food waste, in-depth interviews, qualitative content analysis, social movements Corresponding author: Tel: + 49.8161.71.2536 Email: M. Rombach: [email protected] V. Bitsch: [email protected] 2015 International Food and Agribusiness Management Association (IFAMA). All rights reserved. 1 Rombach and Bitsch Volume18 Issue 3, 2015 Introduction In Germany, food waste occurs in agricultural production, post-harvest, processing and private households (Gustavsson et al. 2011). Food waste is estimated at 11 million tons per year; about 65% of which are avoidable and partly avoidable. The term avoidable refers to food waste that is still safe for human consumption at the time of disposal. -

Ecological Objects in American Poetry

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-8-2014 12:00 AM Dirty Modernism: Ecological Objects in American Poetry Michael D. Sloane The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Joshua Schuster The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Michael D. Sloane 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Continental Philosophy Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Nature and Society Relations Commons Recommended Citation Sloane, Michael D., "Dirty Modernism: Ecological Objects in American Poetry" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIRTY MODERNISM: ECOLOGICAL OBJECTS IN AMERICAN POETRY (Monograph) by Michael Douglas Sloane Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Michael Douglas Sloane 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines how early-to-mid twentieth century American poetry is preoccupied with objects that unsettle the divide between nature and culture. Given the entanglement of these two domains, I argue that American modernism is “dirty.” This designation leads me to sketch what I call “dirty modernism” – a sort of symptom of America’s obsession with cleanliness at the time – which includes the registers of waste, energy, animality, raciality, and sensuality. -

Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster By: Rachel A

Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster By: Rachel A. Vaughn Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Sherrie Tucker ________________________________ Dr Tanya Hart ________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani ______________________________ Dr. Phaedra Pezzullo ________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield Date Defended: Friday, December 2, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Rachel A. Vaughn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Talking Trash: Oral Histories of Food In/Security from the Margins of a Dumpster ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Sherrie Tucker Date approved: December, 2, 2011 ii Abstract This dissertation explores oral histories with dumpster divers of varying food security levels. The project draws from 15 oral history interviews selected from an 18-interview collection conducted between Spring 2008 and Summer 2010. Interviewees self-identified as divers; varied in economic, gender, sexual, and ethnic identity; and ranged in age from 18-64 years. To supplement this modest number of interviews, I also conducted 52 surveys in Summer 2010. I interview divers as theorists in their own right, and engage the specific ways in which the divers identify and construct their food choice actions in terms of individual food security and broader ecological implications of trash both as a food source and as an international residue of production, trade, consumption, and waste policy. This research raises inquiries into the gender, racial, and class dynamics of food policy, informal food economies, common pool resource usage, and embodied histories of public health and sanitation. -

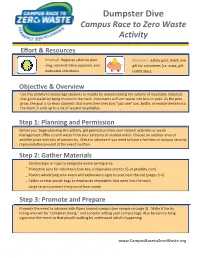

Dumpster Dive Campus Race to Zero Waste Activity

Dumpster Dive Campus Race to Zero Waste Activity Effort & Resources Involved. Requires advance plan- Moderate. Safety gear, thank you ning, administrave approval, and gi for volunteers (i.e. pizza, gi Objecve/Overviewdedicated volunteers. cerficates). Objecve & Overview Use this acvity to encourage students to recycle by demonstrang the volume of recyclable materials that go to waste by being thrown in the trash. Volunteers will sort waste into bins or piles. As the piles Stepgrow, the 1: goal Gather is to show students and thatPrepare every me theyMaterials toss “just one” can, bole, or mobile device into the trash, it adds up to a lot of wasted recyclables. Step 1: Planning and Permission Before you begin planning this acvity, get permission from your student acvies or waste management office to sort waste from your cafeteria or student union. Choose an outdoor area or another place with lots of passers-by. Check in advance if you need to have a facilies or campus security representave present at the event locaon. Step 2: Gather Materials Cauon tape or rope to designate waste sorng area Protecve suits for volunteers (can buy a disposable one for $5 at pksafety.com) Posters adversing your event and explanatory signs to post near the site (pages 3-4) Tables or clear plasc bags to emphasize recyclables that went into the trash Large tarps to protect the ground from waste Step 3: Promote and Prepare Promote the event in advance with flyers around campus (see sample on page 3). Make it fun by listing who will be “dumpster diving,” and consider adding your campus logo. -

The Global Industrial Metabolism of E- Waste Trade a Marxian Ecological Economics Approach

The Global Industrial Metabolism of E- Waste Trade A Marxian Ecological Economics Approach Davor Mujezinovic Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Lancaster University October 2020 Table of Contents Acknowledgment…………………………………………………….……………vii Figures, Tables and Diagrams ……………………………………………………viii Preface ……………………………………………..................................................1 Part 1: Introduction and Background Chapter 1: An Introduction to Informal E-waste Recycling 1. Why study e-waste? …………………………………………………………………………….7 1.1 A brief overview of the e-waste problem ……………………………….………9 2. Composition of WEEE ………………………..……………….................................................11 3. Approaches to studying e-waste - a brief overview ……………………………………….…...15 3.1 Metabolic studies ……………………………………………………………….…………….15 3.2 World systems theory and unequal exchange …….…………………………....18 3.3 Discard studies …………………………………………………………………19 Chapter 2: Theory and Practice 1. Theory: The Materialist Dialectic as a Method of Scientific Inquiry in Studies of Social Metabolism and Socio-Natural Interaction…………………………….24 1.1. Introduction …………..……………………………………………………….25 1.2. Dialectics and the relation between social and natural sciences…27 1.3. Totality and analytical separation in dialectical models ……………………….30 1.4. Dialectics and systems science ………………………………………………...31 1.5. Critical Realism ……………………………………………………………….33 2. Theory to Practice: MFA and micro-ethnography ……………………………………………...37 2.1. -

What Is Zero Waste??

What is Zero Waste?? “Zero Waste is the conservation of all resources by means of responsible production, consumption, reuse, and recovery of products, packaging, and materials without burning, and with no discharges to land, water, or air that threaten the environment or human health.” Peer-reviewed definition of Zero Waste, by the Zero Waste International Alliance www.zwia.org/standards/zw-definition/ Created by Mike Ewall, Energy Justice Network, in conjunction with the Zero Waste International Alliance 215-436-9511; [email protected] OUTLINE VERSION: www.energyjustice.net/zerowaste/ Redesign www.wzia.org/zwh Reduce Source Separate: (reusables, recycling, composting and trash) • Reuse / Repair • Recycle (multi-stream) • Compost (aerobically compost clean organic materials like food scraps and yard waste to return to soils) • Waste: o Waste Composition Research (examine trash to see how the system can be improved upstream) o Material Recovery (mechanically remove additional recyclables that people failed to separate) o Biological Treatment (composting or digestion of organic residuals to stabilize them) o Stabilized Landfilling (biological treatment reduces volume and avoids gas and odor problems) FULL VERSION: Redesign – make products durable, recyclable or Research compostable, and from sustainable / recycled materials • Do a regular waste sort to see what’s left in the waste stream. Use Extended Producer Responsibility Reduce campaigns, product bans and other measures to • Toxics Use Reduction eliminate remaining materials from the waste stream, • Reduce amounts of toxic chemicals in production ensuring that they’re dealt with higher in the hierarchy. • Replace toxic chemicals with less toxic or non- toxic alternatives Material Recovery • Consumption Reduction • For the remaining waste, mechanically pull out • Reduce pervasive advertising additional recyclables. -

Greenwashing/Confusion Criteria for Recycled Content

Topic #1: Purchasing Symbol – greenwashing/confusion Criteria for recycled content – what % is considered -guidelines for buying -Can we purchase as a group? Get cost savings (get on state contract) -Ways big universities can donate bins to small colleges (ex. UNC to App. State) -Create demand for materials Combined waste contract? Nearby schools partnering on contracts/large purchasing -What are cheap ways to buy bins/infrastructure? Metal bin is plastic - more $ up front/more end of life/landfill Topic #2: Special Populations Session #1 Greek Life – Moving from just cardboard from kitchens, not students—issue potential: risk of getting caught Solutions: -Daily recycling pickup from ENS -Working with property managers -Working with kitchens (~500 lbs.) weekly -More @ move-out and in trash -Pair trash can & 96-gallon recycling bin behind each house -Reusable chapter purchases -Takeaway containers -Cups -T-shirts -Get f/s service points LABS -Pick and choose what, when, who gets to touch, enter -Minimal—96-gallon roll cart 1x per month -Recycling difficult unless all are on board -Contaminants = hard to keep out of waste stream Session #2 -Connecting with Greek Life -Consistent signage very important -Knowing what’s recyclable and where it’s going -You can work with DHEC – no cost -Could reach out to Chamber of Commerce -Don’t Waste Food SC -Tourism=19 billion/Recycling=13 billion = econ contribution -Stick-proof gloves Session #3 -Using social media -Email blasting -Community service -Zero waste basketball games -Cheerleader/dancer involvement at games to bring “green spirit” -Atlanta Falcons = Athletic purchasing -lower prices on recyclable items Topic #3: Reuse/Waste Reduction Programs WCU: 1.