University of Bath Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulation and Dysregulation of Chromosome Structure in Cancer

Regulation and Dysregulation of Chromosome Structure in Cancer The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Hnisz, Denes et al. “Regulation and Dysregulation of Chromosome Structure in Cancer.” Annual Review of Cancer Biology 2, 1 (March 2018): 21–40 © 2018 Annual Reviews As Published https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030617-050134 Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/117286 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Regulation and dysregulation of chromosome structure in cancer Denes Hnisz1*, Jurian Schuijers1, Charles H. Li1,2, Richard A. Young1,2* 1 Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, 455 Main Street, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 2 Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA * Corresponding authors Corresponding Authors: Denes Hnisz Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research 455 Main Street Cambridge, MA 02142 Tel: (617) 258-7181 Fax: (617) 258-0376 [email protected] Richard A. Young Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research 455 Main Street Cambridge, MA 02142 Tel: (617) 258-5218 Fax: (617) 258-0376 [email protected] 1 Summary Cancer arises from genetic alterations that produce dysregulated gene expression programs. Normal gene regulation occurs in the context of chromosome loop structures called insulated neighborhoods, and recent studies have shown that these structures are altered and can contribute to oncogene dysregulation in various cancer cells. We review here the types of genetic and epigenetic alterations that influence neighborhood structures and contribute to gene dysregulation in cancer, present models for insulated neighborhoods associated with the most prominent human oncogenes, and discuss how such models may lead to further advances in cancer diagnosis and therapy. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Protein Identities in Evs Isolated from U87-MG GBM Cells As Determined by NG LC-MS/MS

Protein identities in EVs isolated from U87-MG GBM cells as determined by NG LC-MS/MS. No. Accession Description Σ Coverage Σ# Proteins Σ# Unique Peptides Σ# Peptides Σ# PSMs # AAs MW [kDa] calc. pI 1 A8MS94 Putative golgin subfamily A member 2-like protein 5 OS=Homo sapiens PE=5 SV=2 - [GG2L5_HUMAN] 100 1 1 7 88 110 12,03704523 5,681152344 2 P60660 Myosin light polypeptide 6 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MYL6 PE=1 SV=2 - [MYL6_HUMAN] 100 3 5 17 173 151 16,91913397 4,652832031 3 Q6ZYL4 General transcription factor IIH subunit 5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=GTF2H5 PE=1 SV=1 - [TF2H5_HUMAN] 98,59 1 1 4 13 71 8,048185945 4,652832031 4 P60709 Actin, cytoplasmic 1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=ACTB PE=1 SV=1 - [ACTB_HUMAN] 97,6 5 5 35 917 375 41,70973209 5,478027344 5 P13489 Ribonuclease inhibitor OS=Homo sapiens GN=RNH1 PE=1 SV=2 - [RINI_HUMAN] 96,75 1 12 37 173 461 49,94108966 4,817871094 6 P09382 Galectin-1 OS=Homo sapiens GN=LGALS1 PE=1 SV=2 - [LEG1_HUMAN] 96,3 1 7 14 283 135 14,70620005 5,503417969 7 P60174 Triosephosphate isomerase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TPI1 PE=1 SV=3 - [TPIS_HUMAN] 95,1 3 16 25 375 286 30,77169764 5,922363281 8 P04406 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase OS=Homo sapiens GN=GAPDH PE=1 SV=3 - [G3P_HUMAN] 94,63 2 13 31 509 335 36,03039959 8,455566406 9 Q15185 Prostaglandin E synthase 3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=PTGES3 PE=1 SV=1 - [TEBP_HUMAN] 93,13 1 5 12 74 160 18,68541938 4,538574219 10 P09417 Dihydropteridine reductase OS=Homo sapiens GN=QDPR PE=1 SV=2 - [DHPR_HUMAN] 93,03 1 1 17 69 244 25,77302971 7,371582031 11 P01911 HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, -

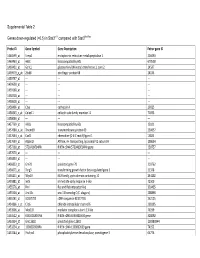

0.5) in Stat3∆/∆ Compared with Stat3flox/Flox

Supplemental Table 2 Genes down-regulated (<0.5) in Stat3∆/∆ compared with Stat3flox/flox Probe ID Gene Symbol Gene Description Entrez gene ID 1460599_at Ermp1 endoplasmic reticulum metallopeptidase 1 226090 1460463_at H60c histocompatibility 60c 670558 1460431_at Gcnt1 glucosaminyl (N-acetyl) transferase 1, core 2 14537 1459979_x_at Zfp68 zinc finger protein 68 24135 1459747_at --- --- --- 1459608_at --- --- --- 1459168_at --- --- --- 1458718_at --- --- --- 1458618_at --- --- --- 1458466_at Ctsa cathepsin A 19025 1458345_s_at Colec11 collectin sub-family member 11 71693 1458046_at --- --- --- 1457769_at H60a histocompatibility 60a 15101 1457680_a_at Tmem69 transmembrane protein 69 230657 1457644_s_at Cxcl1 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 14825 1457639_at Atp6v1h ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit H 108664 1457260_at 5730409E04Rik RIKEN cDNA 5730409E04Rik gene 230757 1457070_at --- --- --- 1456893_at --- --- --- 1456823_at Gm70 predicted gene 70 210762 1456671_at Tbrg3 transforming growth factor beta regulated gene 3 21378 1456211_at Nlrp10 NLR family, pyrin domain containing 10 244202 1455881_at Ier5l immediate early response 5-like 72500 1455576_at Rinl Ras and Rab interactor-like 320435 1455304_at Unc13c unc-13 homolog C (C. elegans) 208898 1455241_at BC037703 cDNA sequence BC037703 242125 1454866_s_at Clic6 chloride intracellular channel 6 209195 1453906_at Med13l mediator complex subunit 13-like 76199 1453522_at 6530401N04Rik RIKEN cDNA 6530401N04 gene 328092 1453354_at Gm11602 predicted gene 11602 100380944 1453234_at -

Molecular Cancer Biomed Central

Molecular Cancer BioMed Central Research Open Access The novel RASSF6 and RASSF10 candidate tumour suppressor genes are frequently epigenetically inactivated in childhood leukaemias Luke B Hesson1, Thomas L Dunwell1, Wendy N Cooper1, Daniel Catchpoole2, Anna T Brini3, Raffaella Chiaramonte4, Mike Griffiths5, Andrew D Chalmers6, Eamonn R Maher1,5 and Farida Latif*1 Address: 1Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, Department of Reproductive and Child Health, Institute of Biomedical Research, Medical School, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, B15 2TT, UK, 2The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Locked Bay 4001, Westmead, NSW, 2145, Australia, 3Department of Medical Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy, 4Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry, Università degli Studi di Milano, via Di Rudinì 8, 20142 Milan, Italy, 5West Midlands Regional Genetics Service, Birmingham Women's Hospital, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TG, UK and 6Centre for Regenerative Medicine, Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Bath, Bath BA2 7AY, UK Email: Luke B Hesson - [email protected]; Thomas L Dunwell - [email protected]; Wendy N Cooper - [email protected]; Daniel Catchpoole - [email protected]; Anna T Brini - [email protected]; Raffaella Chiaramonte - [email protected]; Mike Griffiths - [email protected]; Andrew D Chalmers - [email protected]; Eamonn R Maher - [email protected]; Farida Latif* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 1 July 2009 Received: 20 April 2009 Accepted: 1 July 2009 Molecular Cancer 2009, 8:42 doi:10.1186/1476-4598-8-42 This article is available from: http://www.molecular-cancer.com/content/8/1/42 © 2009 Hesson et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. -

Inhibition of Mitochondrial Complex II in Neuronal Cells Triggers Unique

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Inhibition of mitochondrial complex II in neuronal cells triggers unique pathways culminating in autophagy with implications for neurodegeneration Sathyanarayanan Ranganayaki1, Neema Jamshidi2, Mohamad Aiyaz3, Santhosh‑Kumar Rashmi4, Narayanappa Gayathri4, Pulleri Kandi Harsha5, Balasundaram Padmanabhan6 & Muchukunte Mukunda Srinivas Bharath7* Mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration underlie movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and Manganism among others. As a corollary, inhibition of mitochondrial complex I (CI) and complex II (CII) by toxins 1‑methyl‑4‑phenylpyridinium (MPP+) and 3‑nitropropionic acid (3‑NPA) respectively, induced degenerative changes noted in such neurodegenerative diseases. We aimed to unravel the down‑stream pathways associated with CII inhibition and compared with CI inhibition and the Manganese (Mn) neurotoxicity. Genome‑wide transcriptomics of N27 neuronal cells exposed to 3‑NPA, compared with MPP+ and Mn revealed varied transcriptomic profle. Along with mitochondrial and synaptic pathways, Autophagy was the predominant pathway diferentially regulated in the 3‑NPA model with implications for neuronal survival. This pathway was unique to 3‑NPA, as substantiated by in silico modelling of the three toxins. Morphological and biochemical validation of autophagy markers in the cell model of 3‑NPA revealed incomplete autophagy mediated by mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 2 (mTORC2) pathway. Interestingly, Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor -

Identification of Key Pathways and Genes in Dementia Via Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440371; this version posted July 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Identification of Key Pathways and Genes in Dementia via Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karnataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440371; this version posted July 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract To provide a better understanding of dementia at the molecular level, this study aimed to identify the genes and key pathways associated with dementia by using integrated bioinformatics analysis. Based on the expression profiling by high throughput sequencing dataset GSE153960 derived from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between patients with dementia and healthy controls were identified. With DEGs, we performed a series of functional enrichment analyses. Then, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, modules, miRNA-hub gene regulatory network and TF-hub gene regulatory network was constructed, analyzed and visualized, with which the hub genes miRNAs and TFs nodes were screened out. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed by using receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis. -

Supplementary Information – Postema Et Al., the Genetics of Situs Inversus Totalis Without Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

1 Supplementary information – Postema et al., The genetics of situs inversus totalis without primary ciliary dyskinesia Table of Contents: Supplementary Methods 2 Supplementary Results 5 Supplementary References 6 Supplementary Tables and Figures Table S1. Subject characteristics 9 Table S2. Inbreeding coefficients per subject 10 Figure S1. Multidimensional scaling to capture overall genomic diversity 11 among the 30 study samples Table S3. Significantly enriched gene-sets under a recessive mutation model 12 Table S4. Broader list of candidate genes, and the sources that led to their 13 inclusion Table S5. Potential recessive and X-linked mutations in the unsolved cases 15 Table S6. Potential mutations in the unsolved cases, dominant model 22 2 1.0 Supplementary Methods 1.1 Participants Fifteen people with radiologically documented SIT, including nine without PCD and six with Kartagener syndrome, and 15 healthy controls matched for age, sex, education and handedness, were recruited from Ghent University Hospital and Middelheim Hospital Antwerp. Details about the recruitment and selection procedure have been described elsewhere (1). Briefly, among the 15 people with radiologically documented SIT, those who had symptoms reminiscent of PCD, or who were formally diagnosed with PCD according to their medical record, were categorized as having Kartagener syndrome. Those who had no reported symptoms or formal diagnosis of PCD were assigned to the non-PCD SIT group. Handedness was assessed using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI) (2). Tables 1 and S1 give overviews of the participants and their characteristics. Note that one non-PCD SIT subject reported being forced to switch from left- to right-handedness in childhood, in which case five out of nine of the non-PCD SIT cases are naturally left-handed (Table 1, Table S1). -

Variation in Protein Coding Genes Identifies Information Flow

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/679456; this version posted June 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Animal complexity and information flow 1 1 2 3 4 5 Variation in protein coding genes identifies information flow as a contributor to 6 animal complexity 7 8 Jack Dean, Daniela Lopes Cardoso and Colin Sharpe* 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Institute of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 25 School of Biological Science 26 University of Portsmouth, 27 Portsmouth, UK 28 PO16 7YH 29 30 * Author for correspondence 31 [email protected] 32 33 Orcid numbers: 34 DLC: 0000-0003-2683-1745 35 CS: 0000-0002-5022-0840 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 Abstract bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/679456; this version posted June 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Animal complexity and information flow 2 1 Across the metazoans there is a trend towards greater organismal complexity. How 2 complexity is generated, however, is uncertain. Since C.elegans and humans have 3 approximately the same number of genes, the explanation will depend on how genes are 4 used, rather than their absolute number. -

ASPP Proteins Discriminate Between PP1 Catalytic Subunits Through Their SH3 Domain and the PP1 C-Tail

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08686-0 OPEN ASPP proteins discriminate between PP1 catalytic subunits through their SH3 domain and the PP1 C-tail M. Teresa Bertran1, Stéphane Mouilleron 2, Yanxiang Zhou1, Rakhi Bajaj3, Federico Uliana4, Ganesan Senthil Kumar3, Audrey van Drogen4, Rebecca Lee2, Jennifer J. Banerjee1, Simon Hauri4, Nicola O’Reilly 5, Matthias Gstaiger4, Rebecca Page3, Wolfgang Peti3 & Nicolas Tapon 1 1234567890():,; Serine/threonine phosphatases such as PP1 lack substrate specificity and associate with a large array of targeting subunits to achieve the requisite selectivity. The tumour suppressor ASPP (apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53) proteins associate with PP1 catalytic subunits and are implicated in multiple functions from transcriptional regulation to cell junction remodelling. Here we show that Drosophila ASPP is part of a multiprotein PP1 complex and that PP1 association is necessary for several in vivo functions of Drosophila ASPP. We solve the crystal structure of the human ASPP2/PP1 complex and show that ASPP2 recruits PP1 using both its canonical RVxF motif, which binds the PP1 catalytic domain, and its SH3 domain, which engages the PP1 C-terminal tail. The ASPP2 SH3 domain can discriminate between PP1 isoforms using an acidic specificity pocket in the n-Src domain, providing an exquisite mechanism where multiple motifs are used combinatorially to tune binding affinity to PP1. 1 Apoptosis and Proliferation Control Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute, 1 Midland Road, London NW1 1AT, UK. 2 Structural Biology - Science Technology Platform, The Francis Crick Institute, 1 Midland Road, London NW1 1AT, UK. 3 Chemistry and Biochemistry Department, University of Arizona, 1041 E. -

Agricultural University of Athens

ΓΕΩΠΟΝΙΚΟ ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΑΘΗΝΩΝ ΣΧΟΛΗ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΩΝ ΤΩΝ ΖΩΩΝ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΗΣ ΖΩΙΚΗΣ ΠΑΡΑΓΩΓΗΣ ΕΡΓΑΣΤΗΡΙΟ ΓΕΝΙΚΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΕΙΔΙΚΗΣ ΖΩΟΤΕΧΝΙΑΣ ΔΙΔΑΚΤΟΡΙΚΗ ΔΙΑΤΡΙΒΗ Εντοπισμός γονιδιωματικών περιοχών και δικτύων γονιδίων που επηρεάζουν παραγωγικές και αναπαραγωγικές ιδιότητες σε πληθυσμούς κρεοπαραγωγικών ορνιθίων ΕΙΡΗΝΗ Κ. ΤΑΡΣΑΝΗ ΕΠΙΒΛΕΠΩΝ ΚΑΘΗΓΗΤΗΣ: ΑΝΤΩΝΙΟΣ ΚΟΜΙΝΑΚΗΣ ΑΘΗΝΑ 2020 ΔΙΔΑΚΤΟΡΙΚΗ ΔΙΑΤΡΙΒΗ Εντοπισμός γονιδιωματικών περιοχών και δικτύων γονιδίων που επηρεάζουν παραγωγικές και αναπαραγωγικές ιδιότητες σε πληθυσμούς κρεοπαραγωγικών ορνιθίων Genome-wide association analysis and gene network analysis for (re)production traits in commercial broilers ΕΙΡΗΝΗ Κ. ΤΑΡΣΑΝΗ ΕΠΙΒΛΕΠΩΝ ΚΑΘΗΓΗΤΗΣ: ΑΝΤΩΝΙΟΣ ΚΟΜΙΝΑΚΗΣ Τριμελής Επιτροπή: Aντώνιος Κομινάκης (Αν. Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Ανδρέας Κράνης (Eρευν. B, Παν. Εδιμβούργου) Αριάδνη Χάγερ (Επ. Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Επταμελής εξεταστική επιτροπή: Aντώνιος Κομινάκης (Αν. Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Ανδρέας Κράνης (Eρευν. B, Παν. Εδιμβούργου) Αριάδνη Χάγερ (Επ. Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Πηνελόπη Μπεμπέλη (Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Δημήτριος Βλαχάκης (Επ. Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Ευάγγελος Ζωίδης (Επ.Καθ. ΓΠΑ) Γεώργιος Θεοδώρου (Επ.Καθ. ΓΠΑ) 2 Εντοπισμός γονιδιωματικών περιοχών και δικτύων γονιδίων που επηρεάζουν παραγωγικές και αναπαραγωγικές ιδιότητες σε πληθυσμούς κρεοπαραγωγικών ορνιθίων Περίληψη Σκοπός της παρούσας διδακτορικής διατριβής ήταν ο εντοπισμός γενετικών δεικτών και υποψηφίων γονιδίων που εμπλέκονται στο γενετικό έλεγχο δύο τυπικών πολυγονιδιακών ιδιοτήτων σε κρεοπαραγωγικά ορνίθια. Μία ιδιότητα σχετίζεται με την ανάπτυξη (σωματικό βάρος στις 35 ημέρες, ΣΒ) και η άλλη με την αναπαραγωγική -

Nucleic Acids Research, 2009, Vol

Published online 2 June 2009 Nucleic Acids Research, 2009, Vol. 37, No. 14 4587–4602 doi:10.1093/nar/gkp425 An integrative genomics approach identifies Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1)-target genes that form the core response to hypoxia Yair Benita1, Hirotoshi Kikuchi2, Andrew D. Smith3, Michael Q. Zhang3, Daniel C. Chung2 and Ramnik J. Xavier1,2,* 1Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, 2Gastrointestinal Unit, Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114 and 3Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724, USA Received April 20, 2009; Revised May 6, 2009; Accepted May 8, 2009 ABSTRACT the pivotal mediators of the cellular response to hypoxia is hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), a transcription factor The transcription factor Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 that contains a basic helix-loop-helix motif as well as (HIF-1) plays a central role in the transcriptional PAS domain. There are three known members of the response to oxygen flux. To gain insight into HIF family (HIF-1, HIF-2 and HIF-3) and all are a/b the molecular pathways regulated by HIF-1, it is heterodimeric proteins. HIF-1 was the first factor to be essential to identify the downstream-target genes. cloned and is the best understood isoform (1). HIF-3 is We report here a strategy to identify HIF-1-target a distant relative of HIF-1 and little is currently known genes based on an integrative genomic approach about its function and involvement in oxygen homeosta- combining computational strategies and experi- sis.