Small Farmer Services in India: a Study of Two Blocks in Orissa State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rf,Ivpr, Encl : 1) CD of This Letter : 1 No

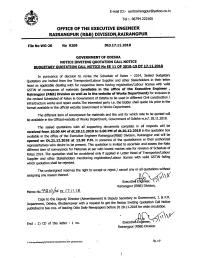

E-mail ID:- [email protected] Tel ,:-06794 222105 OFFICE 0F THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER RAIRANGPUR (R&B) DIVISION,RAIRANGPUR File No WG-20 No 9209 Dtd.17.11.2018 GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA NOTICE INvlnNG QuoTATloN CALL NOTICE quDGETARY QUOTATION CALL NOTICE No EE 11 0F 2018-19 PT 17,11.20u In pursuance of decision to revise the Schedule of Rates - 2014, Sealed budgetary Quotation are invited from the Transporter/Labour Supplier and other Stakeholders in their letter head as applicable dealing with for respective items having registration/Labour license with valid GsllN of conveyance of materials (available in the office of the Executive Engineer , RE!irangpur (R&B) Division as well as in the website of Works Department) for inclusion jn the revised Scheduled of Rates in Government of Odisha to be used in different Civil construction / infrastructure works and repair works.The interested party i.e. the bidder shall qvote his price in the format available in the official website Government in Works Department. The different item of conveyance for materials and the unit for which rate to be quoted will be available in the Official website of Works Department, Government of Odisha w.e.f. 28.11.2018. The sealed quotations with all supporting documents complete in all respects will be received from 10.00 AM of dt.28.11.2018 to 5.00 PM of dt.20.12.2018 in the quotation box available in the office of the Executive Engineer Rairangpur(Ran) Division, Rairangpur and will be opened on Dt.21.12.2018 at 12.30 P.M. -

Tender Call Notice

TENDER CALL NOTICE Sealed Tender are invited from intending individuals / Suppliers / Firms having valid Trade License and GSTIN for supply of the following materials of different model and specification to Rairangpur Forest Division as annexed in Annexure-I of the Tender Notice. A sum of Rs. 5,000/- (Rupees Five Thousand) only per bidder shall be deposited by the intending bidders in the DFO-CUM-DMU CHIEF, RAIRANGPUR FOREST DIVISION A/c No. 39223825840 of State Bank of India, Branch - Rairangpur Branch with IFSC code SBIN0000163 of the Divisional Forest Officer, Rairangpur Forest Division. After completion of tender process, the amount will be refunded to unsuccessful bidders. In case of successful tenderers, the EMD will be converted to performance security deposit. The performance security or security deposit is liable for forfeiture in full or part on violation of terms and conditions of the tenderer. The application form of tender containing General Bid information and terms and conditions for supplying materials will be available in the website www.mayurbhanj.nic.in and can also obtained from the SMS - GIS / MIS, Office of the Divisional Forest Officer, Rairangpur Forest Division on transaction details showing payment of Rs.1000/- (Rupees One Thousand) only through online to A/c No. 39223825840 of State Bank of India, Rairangpur Branch with IFSC code SBIN0000163 towards participation cost/tender cost etc. in the tender process. The amount of Rs.1000/- (Rupees One Thousand) towards Tender cost/participation cost in the process is nonrefundable. The Tender Document downloaded from website and submitted must be accompanied by the deposit of Tender Cost of Rs.1000/- (Rupees One Thousand) in Account Number provided above, failing which the bidding in tender process is liable for rejection. -

Brief Description Champauda O.S. Shop Mayurbhanj District Odisha

BRIEF DESCRIPTION CHAMPAUDA O.S. SHOP MAYURBHANJ DISTRICT ODISHA • Excise Department Govt of Odisha has granted/renewed the Champauda O.S. Shop for producing country liquor with Still Deck Capacity of 1350 Ltrs. with 219 Quintal MGQ capacity Valid upto 31.03.2019. • The license is granted in favour of Sri Sanjib Kumar Beshra, S/o Dillip Kumar Beshra, At: Champauda, PO: Rairangpur, Tehsil: Bijatala Dist: Mayurbhanj, Odisha • The Champauda OS shop installed village Champauda in Bijatala Tehsil of Mayurbhanj district. • The Champauda O.S. shop install over Ac. 0.18 Dec or 0.072 Ha. area • The Location of the project is 87 kms from Baripada the district head quarter and 278 Kms from State head quarter Bhubaneswar. • The project can be approached from Road Joinging Rairangpur to Rengaldeba. • The project area is bounded by Latitude: 22016’51” N Longitude: 86 0 11’ 34.7” E and featured in SOI Toposheet No. 73 J/3 . • Champauda village situated at a distance of 0.5 km from the project site • The nearest National highway Dhenkikote-Kharagpur NH 49 at a distance of 31 kms • The nearest Railway Station at Rairangpur at a distance of 2 kms • Nearest water body is Kadkai River at a distance of 5 km in South direction from the project. • Kuchaiburi reserved forest exists at a distance of 0.5 kms in North direction. • No wildlife or archeological sensitive area exist within 5 kms of project site. • The nearest education and health facility available at Rairangpur distance of 2.0 kms . • The production capacity of the O.S. -

NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA a Progressive Journey Since 2014 Mayurbhanj Parliamentary Constituency

Shri Narendra Modi Hon'ble Prime Minister NEW RAILWAYS NEW ODISHA A progressive journey since 2014 Mayurbhanj Parliamentary Constituency MAYURBHANJ RAILWAYS’ DEVELOPMENT IN ODISHA (2014-PRESENT) MAYURBHANJ PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY A. ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS : Jashipur, Saraskana, Rairangpur, Bangriposi, Udala, Baripada, Morada RAILWAY STATIONS COVERED : Basta, Betnoti, Baripada, N Mayurbhanj Road, Jugpura, Krishna Ch Pura, Thakurtota, Jogal, Badampahar, Kuldiha, Bahalda Road, Aunlajori Junction, Rairanghpur, Gorumahisani, Bangriposi B. WORKS COMPLETED IN LAST FOUR YEARS : B.1. New Lines & Electrication : 90 Kms gauge conversion from Rupsa to Bangriposi at a cost of `183.980 Crore B.2. Improvement of Passenger Amenities Like : Provision of Hand Pump, Benches, Urinals, Latrines, Tube Light with Fittings, LED Fittings, Ceiling Fan, Time Table Display Board at Aunlajori, Chhanua, Birmitrapur, Krishnachandrapur, Jamsole, Baripada, Kuchai, Buramara, Rajaluka, Bangriposi, Bhanjapur Stations at a cost of ` 0.204 Crore. Provision of V.I.P. room and other allied works at Baripada Station at a cost of ` 0.290 Crore. Provision of precast CC grill boundary wall at Betnoti at a cost of ` 0.085 Crore. B.3. Trafc Facilities : Limited Height Subway at LC No. TB66 at a cost of ` 0.950 Crore. B.4. Additional Facilities : Chhanua-Badampahar- Manning of unmanned LC no. TB - 68 73 at Km 33014 - 3311 33509 - 10 at a cost of ` 0.860 Crore. Rairangpur - Development of station as Adarsh Station at a cost of ` 1.060 Crore. Provision of 04 nos hand pump at a cost of ` 0.030 Crore. C. ON-GOING WORKS : C.1. Improvement of Passenger Amenities : Provision of interlocking precast CC blocks at Baripada at a cost of ` 0.080 Crore. -

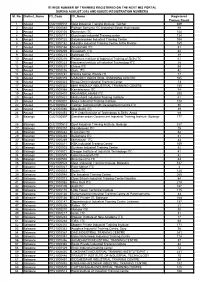

Sl. No. Distirct Name ITI Code ITI Name Registered Trainee

ITI WISE NUMBER OF TRAINEES REGISTERED ON THE NCVT MIS PORTAL DURING AUGUST 2018 AND ISSUED REGISTRATION NUMBERS Sl. No. Distirct_Name ITI_Code ITI_Name Registered Trainee Count 1 Anugul GU21000531 Govt Industrial Training Institute, Talcher 609 2 Anugul PR21000085 Pathani Samanta ITC Industrail Estate Hakimpada 99 3 Anugul PR21000104 Aluminium ITC 144 4 Anugul PR21000113 Gurukrupa industrial Training center 134 5 Anugul PR21000122 Satyanaryanan Industrail Training Centre 104 6 Anugul PR21000142 Adarsha Industrail Training Centre At/Po Rantlei 165 7 Anugul PR21000166 Shivashakti ITC 81 8 Anugul PR21000209 Biswanath ITC 42 9 Anugul PR21000213 Ashirwad ITC 39 10 Anugul PR21000216 Pallahara Institute of Industrial Training of Skills ITC 61 11 Anugul PR21000223 Narayana Institute of Industrial Technology ITC 28 12 Anugul PR21000231 Orissa ITC 59 13 Anugul PR21000235 Guru ITC 42 14 Anugul PR21000281 Pabitra Mohan Private ITI 77 15 Anugul PR21000319 VASUDEV INDUSTRIAL TRAINNING CENTRE 105 16 Anugul PR21000323 Shree Dhriti Industrial Training Center 73 17 Anugul PR21000324 MAA HINGULA INDUSTRIAL TRAINNING CENTRE 155 18 Anugul PR21000368 Kaminimayee ITC 74 19 Anugul PR21000410 AKHANDALAMANI ITC 200 20 Anugul PR21000422 Matrushakti Industrial Training Institute 61 21 Anugul PU21000001 Angul Industrial Training Institute 128 22 Anugul PU21000024 Talcher Technical Edn Development Centre ITC 90 23 Anugul PU21000086 Maa Budhi ITC 39 24 Anugul PU21000453 O P Jindal Institute of Technology & Skills, Angul 69 25 Balangir GU21000507 Gandhamardan Government -

Listof the Homoeopathic Dispensaries MAYURBHANJ Sl

Annexure-I Directorate of Indian Medicines & Homoeopathy, Orissa, Bhubaneswar Listof the Homoeopathic Dispensaries MAYURBHANJ Sl. Name of the Dispensary Name of G. P. Name of the Block Tribal/Non-Tribal No. 1 Marudihi Chikitmatia Muruda Tribal area 2 Gadigaon Gadigaon Muruda Tribal area 3 Chadheigaon Chadheigaon Muruda Tribal area 4 Jualiphanga Gadigaon Muruda Tribal area 5 Kapadiha Joka Saraskana Tribal area 6 Paikasahi Totapada Rasgobindpur Tribal area 7 Mangalpur Jhatiada Rasgobindpur Tribal area 8 Chhadakata Bhaludi Samakhunta Tribal area 9 Patrapada Sialighati Barasahi Tribal area 10 Pratappur Pratappur Barasahi Tribal area 11 Bhimada (tentuligaon) Atisari Barasahi Tribal area 12 Singada Baghada Suliapada Tribal area 13 Khadikapada Anala Betanati Tribal area 14 Pureinia Purenia Betanati Tribal area 15 Ghatakuanri Bramhanigaon Bangiriposi Tribal area 16 Dhighi Dighi Bangiriposi Tribal area 17 Bankisole Bankisole Baripada Tribal area 18 Kuchei Kuchei Kuliana Tribal area 19 Panpos Pantho Josipur Tribal area 20 Manda Bansanali Josipur Tribal area 21 Gadapalsa Gadapalsa Raruan Tribal area 22 Salarpada Batapalsa Karanjia Tribal area 23 Karanjia Karanjia Karanjia Tribal area 24 Pasuda Pasuda Khunta Tribal area 25 Baradihi Baradihi Khunta Tribal area 26 Ranibandha Ranibandha Gopabandhnagar Tribal area 27 Raipal Padmapokhari Kaptipada Tribal area 28 Nududiha Nududiha Kaptipada Tribal area 29 Khuntapala Kuchiladiha Udala Tribal area 30 Analajodi Analajodi Bahalada Tribal area 31 Matiali Matiali Jamada Tribal area 32 Podadiha Bhalubasa Rairangpur Tribal area 33 Baghara road Baripada town Baripada Tribal area 34 Rairangpur Rairangpur Baripada Tribal area 35 Khadambeda Khadambeda Bisoi Tribal area 36 Kusumi Kusumi Kusumi Tribal area 37 Madarangajodi Maudi Josipur Tribal area 38 Khiching Khiching Sukruli Tribal area 39 Kudarsahi Josipur Bahalada Tribal area 40 Bautibeda Bautibeda Bisoi Tribal area 41 Jirai Kulughutu Tiring Tribal area 42 Pundasole Keutunimari Kuliana Tribal area 43 Bagabuda Bagabuda Saraskana Tribal area. -

Get Your New IFSC & MICR Code

SOL- Old IFSC Code (will New New Alloted Sr. No. Erstwhile Circle Zone Branch Name Address Pincode be disabled from 01- New IFSC Code Sol-ID MICR Code Bank 04-2021) 1 168510 OBC1685C Agra Agra Dura-Agra Vill. & Post: Dura, Distt.-Agra, Uttar Pradesh 283110 282024045 ORBC0101685 PUNB0168510 2 035310 OBC0353C Agra Agra Malpura Lampura Agra- 283102 282001 282024044 ORBC0100353 PUNB0035310 3 035210 OBC0352C Agra Agra Jaigara Vpo Jaigara Tehsil Karab Distt Agra- 28312 283122 282024043 ORBC0100352 PUNB0035210 4 035110 OBC0351C Agra Agra Dura-Fatepur Sikri Bypass Duramor Bypass Fatehpur Sikri Agra- 283110 282110 282024042 ORBC0100351 PUNB0035110 Village Ram Nagar Khandoli, Post Branch Khandoli Agra Hathras 5 026010 OBC0260C Agra Agra Ram Nagar Khandoli 282006 282024041 ORBC0100260 PUNB0026010 Road- 283126 82, Ellora Enclave, 100 Feet Road, Dayalbagh, Agra Pin Code - 6 198410 OBC1984C Agra Agra Agra-Dayalbagh 282005 282024040 ORBC0101984 PUNB0198410 2852005 7 146610 OBC1466C Agra Agra Shamsabad 214 Gopal Pura Agra Road Shamshabad-283125 283125 282024039 ORBC0101466 PUNB0146610 8 137210 OBC1372C Agra Agra Fatehabad Road Agra Hotel Luvkush Fatehabad Road Agra-28001 282001 282024038 ORBC0101372 PUNB0137210 D-507 Hotel Woodland , Ghat Wasan , Kamla Nagar, Agra - 9 118610 OBC1186C Agra Agra Agra-Kamla Nagar 282002 282024037 ORBC0101186 PUNB0118610 282005 U.P. 10 523910 OBC5239C Agra Agra Agra-Tehsil Sadar Tehsil Sadar, Agra 282001 282024036 ORBC0105239 PUNB0523910 11 102010 OBC1020C Agra Agra Agra-Bank Colony A 71 Bank Colony Opp Subhash Park M G -

Sr. No. Branch ID Branch Name City Branch Address Branch Timing Weekly Off Micrcode Ifsccode

Sr. No. Branch ID Branch Name City Branch Address Branch Timing Weekly Off MICRCode IFSCCode Khata No- 46/212, Plot No-74, Ghasipura Market Road, Near Bank Of India, Anandapur, 1 3471 Anandpur Anadapur 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 758211003 UTIB0003471 Dist - Keonjhar, Odisha 2 288 Angul Anugul Angul: Orissa,Shreeram Market Complex,Main Road, Angul 759 122,Orissa 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 759211102 UTIB0000288 3 2586 Asika Asika Ground Floor, Near 1938/164,Kalinga Road, Asika, Dist.Ganjam, Orissa, Pin 761110 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 761211202 UTIB0002586 Ground Floor, Ward No-6, Mouza : Athagad , Khata No- 212/1266, Plot No-124/699 , PS 4 3896 Athagad Athagad 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 754211402 UTIB0003896 ; Athagad , Dist: Cuttack, Odisha – 754029 Ground Floor, Hospital Road, Near Primary Health Centre, PO: Badapodaguda, State : 5 3486 Badapodaguda Badapodaguda 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 766211505 UTIB0003486 Odisha, Dist: Kalahandi, Pincode: 766028 Ground Floor Plot no.339/720& 339/927, Khata no. 247/206&247/306, Mouza: 6 2322 Bahadapitha Bahadapitha Bahadapitha, Village: Bahadapitha, P.S : Odagaon, District : Nayagarh, 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 752211506 UTIB0002322 Orissa, Pin 752 081 7 678 Bolangir Balangir Bolangir, Orissa,Tara Complex,Bhagarthi Chowk,Bolangir 767 001, Orissa 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. -

College ID State University College Name Road City District Pin

College ID State University College name Road City District Pin Payable at IFSC No AC No MICR No BBA2-001 Bihar BBA Bihar Awadh Bihari Singh Mahavidyalaya Lalganj Vaishali Canara Bank,Lalganj Vaishali CNRB 0001252 125220150212 BBA2-003 Bihar BBA Bihar Braj Mohan Das College Dayalpur, Vaishali 844502 Allahabad Bank, Dyalpur Vaishali ALLA0210006 20263644708 844010002 BBA2-004 Bihar BBA Bihar Chandradeo Narain College Sahebganj Muzaffarpur 843125 Central Bank of India, Sahebganj Muzaffarpur CBIN0280026 2195891667 26 BBA2-005 Bihar BBA Bihar Dr S K Sinha Women's College Motihari 845401 State Bank of India, Motihari SBIN0001231 10953148213 845002003 BBA2-006 Bihar BBA Bihar Dr Ram Manohar Lohia Smarak Mahavidyalaya Muzaffarpur 842001 Canara Bank, Motijheel,Muzaffarpur CNRB0000258 0258201001285 842015002 BBA2-007 Bihar BBA Bihar Deo Chand College Hajipur, Vaishali 844101 Hajipur SBIN0012572 31505518429 844002004 BBA2-008 Bihar BBA Bihar Dr Jagannath Mishra College Muzaffarpur 842001 United bank of India, Motijheel, Muzaffarpur UTBIOMTJJ07 0825010102000 8420270002 BBA2-010 Bihar BBA Bihar Jagannath Singh College Chandauli Sitamarhi 843316 State Bank of India, Sitamarhi SBIN0004654 11621131845 843002503 BBA2-011 Bihar BBA Bihar Jamunilal Mahavidyalaya Hajipur Vaishali 844101 Punjab National Bank, Hajipur Vaishali PUNB0403700 4037000100062968 844024002 BBA2-013 Bihar BBA Bihar Jeewachh Mahavidyalaya Motipur, Muzaffarpur 843111 Punjab National Bank, Muzaffarpur PUNB0033400 0334000100194870 842024002 BBA2-015 Bihar BBA Bihar Khem Chand Tara Chand -

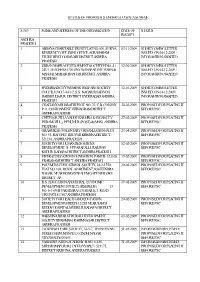

State Wise List Ujjawala Proposals 123456

STATUS OF PROPOSALS UNDER UJJAWALA SCHEME S.NO. NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE ORGANIZATION DATE OF STATUS RECEIPT ANDHRA PRADESH 1 ABHAYA CHARITABLE TRUST FLAT NO.509, SURYA 03-11-2009 SHORTCOMING LETTER RESIDENCY OPP. BSNL OFFICE AGRAHARAM ISSUED ON 04-12-2009 / ELURE WEST GODAVARI DISTRICT ANDHRA INFORAMTION AWAITED PRADESH 2 URBAN MAHILA DEVELOPMENT SOCEITY H.NO. 41- 12-10-2009 SHORTCOMING LETTER 241/1 TEACHERS COLONY WANAPARTHY TOWN & ISSUED ON 04-12-2009 / MANDAL MAHABUBNAGAR DISTRICT ANDHRA INFORAMTION AWAITED PRADESH 3 HYDERBAD CITY WOMENS WELFARE SOCIETY 12-10-2009 SHORTCOMING LETTER COUCIL H.NO 7-40/1/2, S.S. NAGAR ROAD NO.8 ISSUED ON 04-12-2009/ HABSIGUDA R.R. DISTRICT HYDERABAD ANDHRA INFORAMTION AWAITED PRADESH 4 CHAITANYA BHARATHI PLOT. NO. 70, C.B. COLONY 30-03-2009 PROPOSED FOR PLACING IT P.O. CONTONMENT VIZINAGRAM DISTRICT BEFORE PSC ANDHRA PRADESH 5 CHITTOOR ZILLA VADDE KARMIKA SANGAM, T.V. 27-02-2009 PROPOSED FOR PLACING IT PURAM (VILL.), PENUMUR (POST) & (MAN). ANDHRA BEFORE PSC PRADESH 6 GRAMVIKAS (VOLUNTARY ORGANIZATION) PLOT 23-04-2009 PROPOSED FOR PLACING IT NO. 55, RAJUPET TIRUVUR KRISHNA DISTRICT- BEFORE PSC 521234, ANDHRA PRADESH 7 SOCIETY FOR HUMAN RESOURCES 02-02-2009 PROPOSED FOR PLACING IT DEVELOPMENT, S. UPPARAPALLI, RAILWAY BEFORE PSC KODUR, KADAPA DISTRICT ANDHRA PRADESH 8 VIVEKA EDUCATION FOUNDATION, PAMUR- 523108, 19-02-2009 PROPOSED FOR PLACING IT PRAKASAM DISTRICT ANDHRA PRADESH BEFORE PSC 9 POLYMERS EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY, 24-2-1750, 20-02-2009 PROPOSED FOR PLACING IT FLAT NO. 101, ROYAL APARTMENT, RAVEENDRA BEFORE PSC NAGAR, NEAR KONDAYAPALEM GATE NELLORE DISTRICT AP 10 R.S. -

Member List (Mayurbhanj) (A) Baripada

MEMBER LIST (MAYURBHANJ) (A) BARIPADA SN Name of the Company Contact Persons Phone/Fax/Mail ID 1. Ananda Engineering Complex Nityanda Tipathy Ph-06792- Kalikapur, NH-5, Baripada 253622/252522 Mayurbhanj Cell-9937134581 2. Bhabani Stone Crusher Bijoy Kumar Pattnaik Ph -06792 -252578 Lalbazar, Baripada,Mayurbhanj Cell-9437039178 3. Bijay Engineering Bijay Kumar Bala Cell-9437188729 Raghunathpur , Baripada Mayurbhanj 4. Bright Glass Works (P) Ltd Jaydev Benarjee 06792-253214, Kailash Chandra Pur Fax-253832 Baripada, Mayurbhanj 5. Durga Stone Crusher Gaya Prasad Khandelwalla Barbazar, Baripada Mayurbhanj 6. Dwarsuni Layer Firm Radhakanta Sahu Cell No-9437032556 Bhanjpur, Baripada Mayurbhanj 7. Das & Sons Ceramics (P) Ltd N C Das 06794 -272621, Majhigaon, Po- Bahalda Road, Dist- 272631 Mayurbhanj-757054 8. Eastern Feeds Asim Kumar Saikia 06792-262733 Chhancha Industrial Estate Baripada, Mayurbhanj 9. Eastern Patholo Chem (P) Ltd Pritish Majumdar Chhancha Industrial Estate Baripada, Mayurbhanj 10 . Geeta Engineering Works Budhadev Bhanj Chhancha Industial Estate Baripada, Mayurbhanj 11. Hi-Tech Forkul (P) Ltd Diptesh Tripathy Cell-9338871076 Ward No-12, Prafulla Nagar Baripada, Mayurbhanj 12 . Jagannath Industries Baidyanath Mishra Station Road, Baripada Mayurbhanj 13 . Kaling a Foot Wear Soumyarup Das Phone -06792 - Industrial Estate, Takatpur 2558060 Baripada, Mayurbhanj Cell-9437037806 14. Krishna Chorates (P) Ltd Krishna Spinning Mills Kathpal, Baripada, Mayurbhanj 15 . Maghasoni Match Wood (P) Ltd Sudipta Kumar Mohapatra Lalbazar, Baripada, Mayurbhanj 16. MCI Spices 06792- Lalbazar, Baripada, Mayurbhanj 253396,252295 Fax-252395 17 . Mimico Vinyl (P) Ltd Shyam Prakash Singh Chhancha Industrial Estate Baripada, Mayurbhanj 18. Moti Foot Wears Kailash Khandelwal Cell-9861035513 Ward No-1, Babu sahi Baripada, Mayurbhanj North Orissa Chamber of Commerce & Industry, Balasore Page 1 SN Name of the Company Contact Persons Phone/Fax/Mail ID 19 . -

Percentage Presence of Aquatic Species in the Study Area

CONTENTS Sl Chapter Title Page No. No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9-14 1 CHAPTER-1 Introduction to the area and back ground information 15-63 2 CHAPTER-2 Impact of the project on environment. 64-74 3 CHAPTER-3 Objective of management and strategies to mitigate the 75-76 adverse impact. 4 CHAPTER-4 Proposed management strategies within the project area, 77-96 Financial Forecast. 5 CHAPTER-5 Proposed Management strategies within the project impact 97-110 zone, Financial forecast & year wises financial outlay for different interventions spreading over the plan period. 6 CHAPTER-6 Maps and Plates 111 7 References 112 8 Annexures 113-114 A ANNEXURE-I Details of amount deposited to Forest Department and Expenditure for various purposes in respect of Badampahar Iron Ore Mines of M/s Lal Trades & Agencies (P) Ltd... B ANNEXURE-II Extension of validity period of mining lease for lron ore over an area of 129.61 hects in Badampahar of Mayurbhanj district in favour of M/s Lal Trades & Agencies (P) Ltd under section 8A(6) of the MMDR Amendment Act, 2015 C ANNEXURE-III Environmental Clearance in accordance with the provisions of the EIA Notification, 2006 for the Enhancement of Iron Ore from the Badampahar Iron Ore Mines from 0.72 Million TPA to 1.5 Million TPA. The Letter No. – J-11015/39/2018-IA.II(M),dated 27th July 2018 by the Impact assessment Division of Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Government of India. D ANNEXURE-IV Letter No. F.No.8-11l2004-FC, dated 27th July 2009 of Ministry of Forests and Environment for forest Diversion of already broken up land E ANNEXURE-V Letter No.