The New Gilded Age May 24, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Biden Appeals for Unity He Faces a Confluence of Crises Stemming from Pandemic, Insurrection & Race by BRIAN A

V26, N21 Thursday, Jan.21, 2021 President Biden appeals for unity He faces a confluence of crises stemming from pandemic, insurrection & race By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – In what remains a crime scene from the insurrection on Jan. 6, President Joe Biden took the oath of office at the U.S. Capitol Wednesday, appealing to all Americans for “unity” and the survival of the planet’s oldest democ- racy. “We’ve learned again that democracy is precious,” when he declared in strongman fashion, “I alone can fix Biden said shortly before noon Wednesday after taking the it.” oath of office from Chief Justice John Roberts. “Democ- When Trump fitfully turned the reins over to Biden racy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has without ever acknowledging the latter’s victory, it came prevailed.” after the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6 that Senate Minor- His words of assurance came four years to the day ity Leader Mitch McConnell said he had “provoked,” leading since President Trump delivered his dystopian “American to an unprecedented second impeachment. It came with carnage” address, coming on the heels of his Republican National Convention speech in Cleveland in July 2016 Continued on page 3 Biden’s critical challenge By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – Here is the most critical chal- lenge facing President Biden: Vaccinate as many of the 320 million Americans as soon as possible. While the Trump administration’s Operation Warp “Hoosiers have risen to meet Speed helped develop the CO- VID-19 vaccine in record time, these unprecedented challenges. most of the manufactured doses haven’t been injected into the The state of our state is resilient arms of Americans. -

Faircourt, the Kusers, and the Somerset Hills in the “Gilded Age”

FAIRCOURT, THE KUSERS, AND THE SOMERSET HILLS IN THE “GILDED AGE” The communities comprising the Somerset Hills were fundamentally changed following the arrival of the railroad in Bernardsville in 1872 and the subsequent development of the large and luxurious summer resort hotel, the Somerset Inn, on the Bernardsville–Mendham Road. Both factors were key to exposing the area to prominent and affluent families from New York and Newark, many of whom liked what they saw and decided to stay. The original Bernardsville railroad station, from 1872 to 1901-02. It was later moved and is now the Bernardsville News office. The Somerset Inn started as a boarding house in 1870, and grew to become a large and luxurious summer resort hotel hosting up to 400 guests. It burned to the ground in 1908. Except for the periodic excitement created by soldiers in the area during the American Revolution, what had long been a quiet, peaceful and relatively isolated area consisting of small family farms and quaint villages was transformed during the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth into a colony of large and elaborate estates. These properties were designed by some of the country’s most prominent architects and landscape architects for a new class of financiers and industrialists who had amassed enormous fortunes in the years following the Civil War. Although the increasingly crowded, noisy and grimy urban centers were the principal sources of this vast new wealth, these business moguls sought out the open and beautiful rolling countryside of New Jersey as a retreat from the city and a way to capture—and in many ways to create from scratch—what they saw as the fading ideal of the bucolic life. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Mccarthyism and the Big Lie

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1953 McCarthyism and the big lie Milton Howard Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Howard, Milton, "McCarthyism and the big lie" (1953). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 45. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/45 and the BIG LIE McCARTHYISM AND THE BIG LIE By MILTON HOWARD A man is standing on the steps of the US. Trsssnry Buildiig in downtown New York. He irs &outing his contempt for any American who believes we can have peace in tbis world. He says such Americas are "Kremlin dupes." He derides them as "egg-heads and appeaser&" The speaker is Joe McCarthy, U.S. Senator from Wisconsin. He holds the crowd's attention. He has studied the trade of lashing hysteria into rm audience. Five years ago, he was a little known pvliti- . cian. Today, his name has become known throughout the world. .Hehas baptized the poIitical fact known as McCarthykn. Americans began to get a whiff of this new fact when millions eud- denly faced what is now known as "The Reign of Fear." Three years ago, the President of the U.S.A. startled the world. He said that the American citizens of the state of Wisconsin were afraia. -

Excerpts of Record in Support of Appellants' Opening Brief, Vol. 3

Case: 13-17430 02/03/2014 ID: 8963820 DktEntry: 15-5 Page: 1 of 181 No. 13-17430 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, ET AL., Defendants-Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court, Northern District of California D.C. No. CV-09-0037-CW The Honorable Claudia Wilken, Judge Presiding EXCERPTS OF RECORD IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS’ OPENING BRIEF, VOL. 3, PP. 579–757 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP James P. Bennett Eugene Illovsky Stacey M. Sprenkel Ben Patterson 425 Market Street San Francisco, California 94105 Telephone: (415) 268-7000 Attorneys for Appellants Case: 13-17430 02/03/2014 ID: 8963820 DktEntry: 15-5 Page: 2 of 181 DISTRICT COURT DATE FILED DOCUMENT DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. DOCKET NO. 11/18/2010 Third Amended Complaint for 180 579 Declaratory and Injunctive Relief Under United States Constitution and Federal Statutes and Regulations Docket Report for U.S.D.C. (N.D. 655 Cal.) Case No. 09-cv-0037-CW, Vietnam Veterans of America et al. v. Central Intelligence Agency et al. sf-3377831 Case: 13-17430Case4:09-cv-00037-CW 02/03/2014 Document180 ID: 8963820 Filed11/18/10 DktEntry: 15-5Page1of76 Page: 3 of 181 1 GORDONP. ERSPAMER (CA SBN 83364) [email protected] 2 TIMOTHY W. BLAKELY (CA SBN 242178) [email protected] 3 STACEY M. SPRENKEL (CA SBN 241689) [email protected] 4 DANIEL 1. VECCHIO (CA SBN 253122) [email protected] 5 DIANA LUO (CA SBN 233712) [email protected] 6 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP 425 Market Street 7 San Francisco, California 94105-2482 Telephone: 415.268.7000 8 Facsimile: 415.268.7522 9 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Vietnam Veterans ofAmerica; Swords to Plowshares: Veterans 10 Rights Organization; Bruce Price; Franklin D. -

Marx and Mendacity: Can There Be a Politics Without Hypocrisy?

Analyse & Kritik 01+02/2015 (© Lucius & Lucius, Stuttgart) S. 521 Martin Jay Marx and Mendacity: Can There Be a Politics without Hypocrisy? Abstract: As demonstrated by Marx's erce defence of his integrity when anonymously accused of lying in l872, he was a principled believer in both personal honesty and the value of truth in politics. Whether understood as enabling an accurate, `scientic' depiction of the contradictions of the present society or a normative image of a truly just society to come, truth-telling was privileged by Marx over hypocrisy as a political virtue. Contemporary Marxists like Alain Badiou continue this tradition, arguing that revolutionary politics should be understood as a `truth procedure'. Drawing on the alternative position of political theorists such as Hannah Arendt, who distrusted the monologic and absolutist implications of a strong notion of truth in politics, this paper defends the role that hypocrisy and mendacity, understood in terms of lots of little lies rather than one big one, can play in a pluralist politics, in which, pace Marx, rhetoric, opinion and the clash of values resist being subsumed under a singular notion of the truth. 1. Introduction In l872, an anonymous attack was launched in the Berlin Concordia: Zeitschrift für die Arbeiterfrage against Karl Marx for having allegedly falsied a quotation from an 1863 parliamentary speech by the British Liberal politician, and future Prime Minister, William Gladstone in his own Inaugural Address to the First International in l864. The polemic was written, so it was later disclosed, by the eminent liberal political economist Lujo Brentano.1 Marx vigorously defended himself in a response published later that year in Der Volksstaat, launching a bitter debate that would drag on for two decades, involving Marx's daughter Eleanor, an obscure Cambridge don named Sedly Taylor, and even Gladstone himself, who backed Brentano's version. -

Early Birding Book

Early Birding in Dutchess County 1870 - 1950 Before Binoculars to Field Guides by Stan DeOrsey Published on behalf of The Ralph T. Waterman Bird Club, Inc. Poughkeepsie, New York 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Stan DeOrsey All rights reserved First printing July 2016 Digital version June 2018, with minor changes and new pages added at the end. Digital version July 2019, pages added at end. Cover images: Front: - Frank Chapman’s Birds of Eastern North America (1912 ed.) - LS Horton’s post card of his Long-eared Owl photograph (1906). - Rhinebeck Bird Club’s second Year Book with Crosby’s “Birds and Seasons” articles (1916). - Chester Reed’s Bird Guide, Land Birds East of the Rockies (1908 ed.) - 3x binoculars c.1910. Back: 1880 - first bird list for Dutchess County by Winfrid Stearns. 1891 - The Oölogist’s Journal published in Poughkeepsie by Fred Stack. 1900 - specimen tag for Canada Warbler from CC Young collection at Vassar College. 1915 - membership application for Rhinebeck Bird Club. 1921 - Maunsell Crosby’s county bird list from Rhinebeck Bird Club’s last Year Book. 1939 - specimen tag from Vassar Brothers Institute Museum. 1943 - May Census checklist, reading: Raymond Guernsey, Frank L. Gardner, Jr., Ruth Turner & AF [Allen Frost] (James Gardner); May 16, 1943, 3:30am - 9:30pm; Overcast & Cold all day; Thompson Pond, Cruger Island, Mt. Rutson, Vandenburg’s Cove, Poughkeepsie, Lake Walton, Noxon [in LaGrange], Sylvan Lake, Crouse’s Store [in Union Vale], Chestnut Ridge, Brickyard Swamp, Manchester, & Home via Red Oaks Mill. They counted 117 species, James Gardner, Frank’s brother, added 3 more. -

Spring Volume 9 Number 1

Spring 1972 Volume 9 Number 1 Ramsey County History Published by the RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Editor: Virginia Brainard Kunz Contents Spring Old Federal Courts Building — Beautiful, Unique — Its Style 1972 of A rchitecture Faces Extinction Volume 9 By Eileen Michels................................. A Teacher Looks Back at PTA, 4-H — Number 1 And How a Frog in a Desk Drawer Became a Lesson in Biology By Alice Olson....................................... Forgotten Pioneers . XII....................... North St. Paul’s ‘Manufactories’ Come-back After 1893 Bust’ By Edward J. Lettermann..................... RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY is published semi ON THE COVER: The Old Federal Courts Building, annually and copyrighted, 1972, by the Ramsey County viewed from across Rice Park about 1905. With the Historical Society, 2097 Larpenteur Avenue West, St. park itself, and the Minneapolis Public Library directly Paul, Minnesota. Membership in the Society carries across from it, the Old Federal Courts Building lends with it a subscription to Ramsey County History. Single a sense of community to the area. issues sell for $1.50. Correspondence concerning con tributions should be addressed to the editor. The Society assumes no responsibility for statements made by con tributors. Manuscripts and other editorial material are welcomed but no payment can be made for contribu ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The editor is indebted to tions. All articles and other editorial material submitted Eugene Becker and Dorothy Gimmestad of the Minne will be carefully read and published, if accepted, as sota Historical Society’s audio-visual staff for their help space permits. with the pictures used in this issue. 2 Old Federal Courts Building-- Beautiful, Unique-- OfArchitecture Faces Extinction By Eileen Michels UILT at a cost of nearly $2,500,000 B between 1892 and 1901, the United States Post Office, Court House and Customs House, known colloquially now as the Old Federal Courts Building, was the pride of downtown St. -

POLITICAL SPEECH, DOUBLESPEAK, and CRITICAL-THINKING SKILLS in AMERICAN EDUCATION by Doris E. Minin-White a Capstone Project

POLITICAL SPEECH, DOUBLESPEAK, AND CRITICAL-THINKING SKILLS IN AMERICAN EDUCATION by Doris E. Minin-White A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in English as a Second Language. Hamline University Saint Paul, Minnesota December, 2017 Capstone Project Trish Harvey Content Expert: Joseph White 2 My Project In this project, I will attempt to identify and analyze common cases of doublespeak in selected samples of political discourse, delivered by the two most recent U. S. presidents: Barack Obama and Donald Trump. The sample will include the transcripts from two speeches and two debates for each of the speakers. The speeches chosen will be their inaugural addresses and their presidential nomination acceptance speeches. The debates will be the first and second debates held, as part of the presidential campaign, in which the selected speakers participated. I chose to include speeches from the presidential inaugural address because they represent, perhaps, the greatest opportunity for presidents to speak with impact to the people they represent and to their fellow lawmakers who are generally present at the inauguration. I also chose the speeches they made when accepting the presidential nominations of their respective parties, because it is their opportunity to outline what their party’s platform is, what they feel are the important issues of the day, and how they intend to pursue those issues. Finally, I chose presidential debates because political discourse in this context is more spontaneous. According to the Commission on Presidential Debates (2017), a non-partisan entity that has organized presidential debates in the United States since 1988, political debates are carefully prepared and organized. -

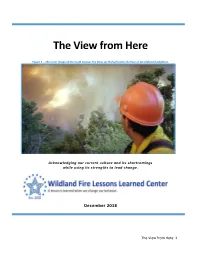

The View from Here

The View from Here Figure 1 -- The iconic image of the South Canyon Fire blow-up that will claim the lives of 14 wildland firefighters. Acknowledging our current culture and its shortcomings while using its strengths to lead change. December 2018 The View from Here 1 This collection represents collective insight into how we operate and why we must alter some of our most ingrained practices and perspectives. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 I Risk ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. The Illusion of Control ............................................................................................................. 5 2. It’s Going to Happen Again ................................................................................................... 14 3. The Big Lie – Honor the Fallen .............................................................................................. 19 4. The Problem with Zero ......................................................................................................... 26 5. RISK, GAIN, and LOSS – What are We Willing to Accept? .................................................... 29 6. How Do We Know This Job is Dangerous? ............................................................................ 39 II Culture ....................................................................................................................................... -

Two Architects, One Island by Sargent C

Two Architects, One Island By Sargent C. Gardiner Since the late nineteenth century, architects and designers of national prominence have been designing houses, landscapes, and other structures on Mount Desert Island, attracted by the strikingly beautiful landscape, the character of which heavily influenced the work they produced. Two of the most notable of these architects were William Ralph Emerson (1833–1917) and Bruce Price (1845– 1903), who designed a range of forward-looking residential projects that responded to the specific topography and natural context of Mount Desert Island. Although very different, both architects produced designs in what is now known as the “Shingle Style,” bringing a synthesis of nineteenth-century American domestic architectural styles to Mount Desert Island that, up to that point, had seen a predominantly local, vernacular building tradition in the form of Greek Revival structures. While Emerson was a regionally focused architect working primarily in New England, the houses he designed on Mount Desert Island represented the introduction of a contemporary style into the region. By contrast, Price was a nationally renowned architect with a more cosmopolitan career executing designs from his New York Studio in a range of locations, types, and styles. Price’s designs on Mount Desert bracket Emerson’s work, built before and after the 1880s, the decade when Emerson designed his most important houses in Bar Harbor. When viewed together, Emerson’s and Price’s designs on Mount Desert Island exemplify the development of a Shingle Style that incorporates earlier regional architectural forms and adapts to the specific geographic conditions of Mount Desert Island. -

The Canadian Rail the Chateau Style Hotels

THE CANADIAN RAIL A. THE CHATEAU STYLE HOTELS 32 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 18:2 WAY HOTEL REVISITED: OF ROSS & MACFARLANE 18.2 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 33 Figure 6 (previous page). Promotional drawing of the Chateau Laurier Hotel, Ottawa, showing (left to right) the Parliament Buildings, Post Office, Chateau Laurier Hotel, and Central Union Passenger Station. Artist unknown, ca. 1912. (Ottawa City Archives, CA7633) Figure 1 (right). Chateau Frontenac Hotel, Quebec City, 1892-93; Bruce Price, architect. (CP Corporate Archives, A-4989) TX ~h the construction of the Chateau Frontenac Hotel in 1892-93 on the heights of r r Quebec City (figure 1), American architect Bruce Price (1845-1903) introduced the chateau style to Canada. Built for the Canadian Pacific Railway, the monumental hotel estab lished a precedent for a series of distinctive railway hotels across the country that served to as sociate the style with nationalist sentiment well into the 20th century.1 The prolonged life of the chateau style was not sustained by the CPR, however; the company completed its last chateauesque hotel in 1908, just as the mode was being embraced by the CPR's chief com petitor, the Grand Trunk Railway. How the chateau style came to be adopted by the GTR, and how it was utilized in three major hotels- the Chateau Laurier Hotel in Ottawa, the Fort Garry Hotel in Winnipeg, and the Macdonald Hotel in Edmonton -was closely related to the background and rise to prominence of the architects, Montreal natives George Allan Ross (1879-1946) and David Huron MacFarlane (1875-1950). According to Lovell's Montreal City Directory, 1900-01, George Ross2 worked as a draughtsman in the Montreal offices of the GTR, which was probably his first training in ar chitecture, and possibly a consideration when his firm later obtained the contracts for the GTR hotels.