Mining Postsocialism: Work, Class and Ethnicity in an Estonian Mine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virumaa Hiied

https://doi.org/10.7592/MT2017.66.kaasik Virumaa hiied Ahto Kaasik Teesid: Hiis on ajalooline looduslik pühapaik, millega seostub ohverdamisele, pühakspidamisele, ravimisele, palvetamisele või muule usulisele või taialisele tegevusele viitavaid pärimuslikke andmeid. Üldjuhul on hiis küla pühapaik, rahvapärimuse järgi olevat varem olnud igal külal oma hiis. Samas on mõnda hiiepaika kasutanud terve kihelkond. Artiklis on vaatluse all Virumaa pühapaigad ning ära on toodud Virumaal praeguseks teada olevate hiite nimekiri. Märksõnad: hiis, looduslik pühapaik, Virumaa Eestis on ajalooliste andmete põhjal teada ligikaudu 800 hiit, neist ligi kuuendik Virumaal. Arvestades, et andmed hiitest on jõudnud meieni läbi aastasadade täis sõdu, taude, otsest hävitamist ja ärakeelamist ning usundilise maailmapildi muutumist, on see aukartustäratav hulk. Hiis ühendab kogukonda ja laiemalt rahvast. Hiis täidab õige erinevaid ülesandeid ning on midagi enamat kui looduskaitseala, kooskäimis- või tantsu- koht, vallamaja, haigla, kalmistu, kirik, kohtumaja, kindlus või ohvrikoht. Hiie suhtes puudub tänapäeval kohane võrdlus. Hiis on hiis. Ajalooliste looduslike pühapaikade hulgas moodustavad hiied eraldi rühma. Samma küla Tamme- aluse hiide on rahvast mäletamistmööda kogunenud kogu Mahu (Viru-Nigula) kihelkonnast (Kaasik 2001; Maran 2013). Hiienimelised paigad on ajalooliselt levinud peamiselt põhja pool Tartu – Viljandi – Pärnu joont (Valk 2009: 50). Lõuna pool võidakse sarnaseid pühapai- kasid nimetada kergo-, kumarus-, pühä-, ahi- vm paigaks. Kuid ka Virumaal ei nimetata hiiesarnaseid paiku alati hiieks. Selline on näiteks Lavi pühapaik. Hiietaolisi pühapaikasid leidub meie lähematel ja kaugematel hõimurah- vastel. Sarnased on ka pühapaikadega seotud tõekspidamised ja tavad. Nõnda annavad hiied olulise tähendusliku lisamõõtme meie kuulumisele soome-ugri http://www.folklore.ee/tagused/nr66/kaasik.pdf Ahto Kaasik rahvaste perre. Ja see pole veel kõik. -

USCAK Soccer Team Competes at Inaugural Ukrainian Tournament In

INSIDE: • Ukraine: a separate but equal buffer zone? — page 3. • National Deputy Anatolii Kinakh visits D.C. — page 8. • Art installations at UIA inspired by “koliada” — page 15. HE KRAINIAN EEKLY T PublishedU by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profitW association Vol. LXXV No. 6 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2007 $1/$2 in Ukraine Controversial law on Cabinet Tymoshenko leads the charge becomes official in Ukraine to protect gas transit system by Zenon Zawada dent’s veto – also a first in Ukraine’s leg- by Zenon Zawada Kyiv Press Bureau islature. Kyiv Press Bureau As a result, Prime Minister Viktor KYIV – The January 12 Cabinet of Yanukovych is now the most influential KYIV – Parliamentary opposition Ministers law significantly enhancing the person in Ukrainian government, and leader Yulia Tymoshenko led the authority of the prime minister and the members of his Cabinet have already Verkhovna Rada to vote overwhelmingly Cabinet of Ministers at the expense of the begun referring to President Viktor on February 7 for a law protecting the president was published on February 2 in Yushchenko as a national figurehead. nation’s critical natural gas transit system the government’s two daily newspapers – “Viktor Yushchenko is the president, from foreign interests, namely the the final step for a law to become official. but I treat national symbols with the Russian Federation’s government and its It was the first law ever passed during appropriate piety,” said Minister of cadre of oligarchs. Ukraine’s 15-plus -

Changes in Climate, Catchment Vegetation and Hydrogeology As the Causes of Dramatic Lake-Level Fluctuations in the Kurtna Lake District, NE Estonia

Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2014, 63, 1, 45–61 doi: 10.3176/earth.2014.04 Changes in climate, catchment vegetation and hydrogeology as the causes of dramatic lake-level fluctuations in the Kurtna Lake District, NE Estonia Marko Vainu and Jaanus Terasmaa Institute of Ecology, Tallinn University, Uus-Sadama 5, 10120 Tallinn, Estonia; [email protected], [email protected] Received 25 March 2013, accepted 2 October 2013 Abstract. Numerous lakes in the world serve as sensitive indicators of climate change. Water levels for lakes Ahnejärv and Martiska, two vulnerable oligotrophic closed-basin lakes on sandy plains in northeastern Estonia, fell more than 3 m in 1946– 1987 and rose up to 2 m by 2009. Earlier studies indicated that changes in rates of groundwater abstraction were primarily responsible for the changes, but scientifically sound explanations for water-level fluctuations were still lacking. Despite the inconsistent water-level dataset, we were able to assess the importance of changing climate, catchment vegetation and hydrogeology in water-level fluctuations in these lakes. Our results from water-balance simulations indicate that before the initiation of groundwater abstraction in 1972 a change in the vegetation composition on the catchments triggered the lake-level decrease. The water-level rise in 1990–2009 was caused, in addition to the reduction of groundwater abstraction rates, by increased precipitation and decreased evaporation. The results stress that climate, catchment vegetation and hydrogeology must all be considered while evaluating the causes of modern water-level changes in lakes. Key words: lake-level fluctuations, groundwater abstraction, climate change, catchment, water balance. -

In Pursuit of Liberalism Epstein, Rachel A

In Pursuit of Liberalism Epstein, Rachel A. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Epstein, Rachel A. In Pursuit of Liberalism: International Institutions in Postcommunist Europe. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3346. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3346 [ Access provided at 30 Sep 2021 14:57 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... In Pursuit of Liberalism . ................................................................................................................................ ........................................................................................................................................................... This page intentionally left blank ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... In Pursuit of Liberalism . International Institutions in Postcommunist Europe . rachel a. epstein . The Johns Hopkins University -

Rahvastiku Ühtlusarvutatud Sündmus- Ja Loendusstatistika

EESTI RAHVASTIKUSTATISTIKA POPULATION STATISTICS OF ESTONIA __________________________________________ RAHVASTIKU ÜHTLUSARVUTATUD SÜNDMUS- JA LOENDUSSTATISTIKA REVIEWED POPULATION VITAL AND CENSUS STATISTICS Ida-Virumaa 1965-1990 Kalev Katus Allan Puur Asta Põldma Aseri Kohtla Lüganuse Toila JÕHVI Sonda Jõhvi Sinimäe Maidla Mäetaguse Illuka Tudulinna Iisaku Alajõe Avinurme Lohusuu Tallinn 2002 EESTI KÕRGKOOLIDEVAHELINE DEMOUURINGUTE KESKUS ESTONIAN INTERUNIVERSITY POPULATION RESEARCH CENTRE RAHVASTIKU ÜHTLUSARVUTATUD SÜNDMUS- JA LOENDUSSTATISTIKA REVIEWED POPULATION VITAL AND CENSUS STATISTICS Ida-Virumaa 1965-1990 Kalev Katus Allan Puur Asta Põldma RU Seeria C No 19 Tallinn 2002 © Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre Kogumikuga on kaasas diskett Ida-Virumaa rahvastikuarengut kajastavate joonisfailidega, © Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus. The issue is accompanied by the diskette with charts on demographic development of Ida-Virumaa population, © Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre. ISBN 9985-820-66-5 EESTI KÕRGKOOLIDEVAHELINE DEMOUURINGUTE KESKUS ESTONIAN INTERUNIVERSITY POPULATION RESEARCH CENTRE Postkast 3012, Tallinn 10504, Eesti Kogumikus esitatud arvandmeid on võimalik tellida ka elektroonilisel kujul Lotus- või ASCII- formaadis. Soovijail palun pöörduda Eesti Kõrgkoolidevahelise Demouuringute Keskuse poole. Tables presented in the issue on diskettes in Lotus or ASCII format could be requested from Estonian Interuniversity Population Research -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information The Genetic History of Northern Europe Alissa Mittnik1,2, Chuan-Chao Wang1, Saskia Pfrengle2, Mantas Daubaras3, Gunita Zarina4, Fredrik Hallgren5, Raili Allmäe6, Valery Khartanovich7, Vyacheslav Moiseyev7, Anja Furtwängler2, Aida Andrades Valtueña1, Michal Feldman1, Christos Economou8, Markku Oinonen9, Andrejs Vasks4, Mari Tõrv10, Oleg Balanovsky11,12, David Reich13,14,15, Rimantas Jankauskas16, Wolfgang Haak1,17, Stephan Schiffels1 and Johannes Krause1,2 1Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany 2Institute for Archaeological Sciences, Archaeo- and Palaeogenetics, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany 3Department of Archaeology, Lithuanian Institute of History, Vilnius 4Institute of Latvian History, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia 5The Cultural Heritage Foundation, Västerås, Sweden 6|Archaeological Research Collection, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia 7Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) RAS, St. Petersburg, Russia 8Archaeological Research Laboratory, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 9Finnish Museum of Natural History - LUOMUS, University of Helsinki, Finland 10Independent researcher, Estonia 11Research Centre for Medical Genetics, Moscow, Russia 12Vavilov Institute for General Genetics, Moscow, Russia 13Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA 14Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA 15Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts -

Interim Report Оn Presidential Elections 2019 Part II

NGO «EUROPEAN COORDINATION COUNCIL» IN COLLABORATION WITH «SENATE OF PUBLIC WARDING» are monitoring the election of the President of Ukraine in 2019 as official observers, in accordance with the Resolution of the Central Election Commission No. 50 dated January 11, 2019. Interim Report оn Presidential Elections 2019 Part II Kyiv 2019 NGO “EUROPEAN COORDINATION COUNCIL” NGO “SENATE OF PUBLIC WARDING”Ā CONTENT Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 І. Registration of the candidates to the post as President of Ukraine, basic themes of the election programs, their main points…....................................................................5 Zelenskyi Volodymyr Oleksandrovych .............................................................................6 Tymoshenko Yuliya Volodymyrivna ................................................................................7 Poroshenko Petro Oleksiyovych ........................................................................................8 Boiko Yurii Anatoliyovych ................................................................................................9 Grytsenko Anatolii Stepanovych ......................................................................................10 Lyashko Oleg Valeriyovych .............................................................................................11 Murayev Evgenii Volodymyrovych .................................................................................12 -

Lüganuse Valla Teehoiukava Aastateks 2019-2022

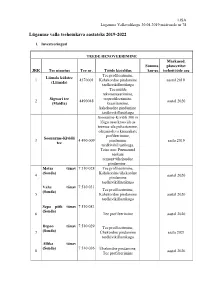

LISA Lüganuse Vallavolikogu 30.04.2019 määrusele nr 78 Lüganuse valla teehoiukava aastateks 2019-2022 1. Investeeringud TEEDE RENOVEERIMINE Märkused, Summa planeeritav JRK Tee nimetus Tee nr. Tööde kirjeldus km-ga teehoitööde aeg Tee profileerimine, Liimala külatee 1 4370001 Kahekordne pindamine aastal 2019 (Liimala) tardkivikillustikuga Tee mulde rekonstrueerimine, Sigwari tee teeprofileerimine, 2 4490048 aastal 2020 (Maidla) kraavitamine, kahekordne pindamine tardkivikillustikuga Soonurme-Kiviõli 300 m lõigu osas kraavide ja teemaa-ala puhastamine, olemasoleva kruusakate profileerimine, Soonurme-Kiviõli 3 4 490 009 pindamine aasta 2019 tee tardkivikillustikuga. Teise osa: Purunenud teekate remont+ühekordne pindamine . Metsa tänav 7 510 028 Tee profileerimine, (Sonda) Kahekordne/ühekordne 4 aastal 2020 pindamine tardkivikillustikuga Vahe tänav 7 510 031 (Sonda) Tee profileerimine, 5 Kahekordne pindamine aastal 2020 tardkivikillustikuga Sepa põik tänav 7 510 081 (Sonda) 6 Tee profileerimine aastal 2020 Depoo tänav 7 510 029 Tee profileerimine, 7 (Sonda) Ühekordne pindamine aasta 2021 tardkivikillustikuga Allika tänav (Sonda) 7 510 036 Ühekordne pindamine, 8 aastal 2020 Tee profileerimine Uueküla-Sadama Tee profileerimine, 9 tee (mäest alla- 4 370 003 Kahekordne pindamine aastal 2020 Tulivee ristini) tardkivikillustikuga Kippari teeotsani pinnatud, sealt Purtse-Sillaoru tee Ühekordne pindamine 10 4370059 4 867 edasi Sigwarini (Kippar) tardkivikillustikuga tegemata. Aasta 2021 11 Metsa tn (Püssi ) Freesimine,asfalteerimine Aasta 2020/2021 -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

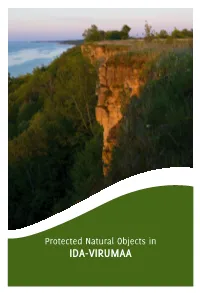

Protected Natural Objects in IDA-VIRUMAA Protected Natural Objects in IDA-VIRUMAA 2 3

Protected Natural Objects in IDA-VIRUMAA Protected Natural Objects in IDA-VIRUMAA 2 3 CONTENTS Protected areas related to klint ...... 7 Protected areas related to rivers .... 13 Unique topography .............. 15 Lakes ........................ 18 Wetlands ..................... 21 Oak forests and wooded meadows ... 30 Natural forests ................. 33 Dunes ....................... 33 Parks ........................ 36 Protected individual objects ....... 38 References .................... 41 ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORITY OF PROTECTED NATURAL OBJECTS Environmental Board Viru Region 15 Pargi Str., 41537 Jõhvi Phone +372 332 4401 [email protected] www.keskkonnaamet.ee ARRANGEMENT OF VISITS TO PROTECTED NATURAL OBJECTS North-Estonian District Nature Management Department State Forest Management Centre (RMK) Phone +372 339 3833 [email protected] www.rmk.ee Compiled by: Anne-Ly Feršel Special thanks to the workers of the Viru Region of the Environmental Board. Front page photo: Ontika Cliff, L. Michelson Publication supported by Back page photo: Environmental Investment Centre Selisoo Mire, L. Michelson Layout by: Akriibia Ltd. Translated by: K. Nurm Editor of map: Areal Disain Printed by: AS Printon Trükikoda ©Environmental Board 2012 Foto: Lynx, C. M. Feršel 4 5 Photo: Semicoke hills near Kohtla-Järve, L. Michelson The landscape of Ida-Viru County (Ida-Virumaa) is diversified. Its northern part lies on the Photo: Northern coast of Lake Peipsi, L. Michelson Viru Plateau and on the klint running along the Gulf of Finland. In the south, however, there is the Alutaguse Lowland and the more than 50-kilometre-long shore of Lake Peipsi. The eastern border runs along the Narva River and Reservoir for 77 kilometres. In the south-west and west, there are large areas of forests and wetlands. -

Ida-Virumaa Functional Review

IDA-VIRUMAA FUNCTIONAL REVIEW IDA-VIRU COUNTY GOVERNMENT, TARTU-JÕHVI-NARVA, 2018 1 Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Analysis of the regional context and the innovation potential ....................................................... 6 2.1. Ida-Virumaa economic structure and the importance of blue economics ................................ 9 2.2. Ida-Virumaa SWOT – general economic development ........................................................... 13 2.3. Ida-Virumaa Blue Growth SWOT ............................................................................................. 14 2.4. Ida-Virumaa R&D capacity ....................................................................................................... 14 2.5. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 14 3. The RIS3 process ............................................................................................................................. 16 4. Potential stakeholders overview – understanding the target group ............................................ 22 5. A vision – Ida-Virumaa in the Baltic Sea Region ............................................................................ 25 VISION ................................................................................................................................................. 25 -

Eesti Kirjandus

EESTI KIRJANDUS EESTI KIRJANDUSE SELTSI VÄLJAANNE TOIMKOND: J. AAVIK, A. R. CEDERBERG, M. J. EISEN, V. GRÜNTHAL, J. JÕGEVER f, A. JÜRGENSTEIN, L. KET- TUNEN, J. KÕPP, J. LUIGA, A. SAARESTE- --— >»» >»«»>,»,,»»» >,»lw«»>>,l» ni TEGEV TOIMETAJA J. V. VESiu5fer£Ö"£. KAHEKSATEISTKÜMNES AASTAKÄIK 10Ö4 HARJUMAA C3C:M..A^ATÜK0GU Jlif j^jpT' & % * L.A/v*- • -'-1 ^^^W^WZ XCs? / EESTI KIRJANDUSE SELTSI KIRJASTUS -^ <f^f»~jTT* EESTI KIRJANDUS EESTI KIRJANDUSE SELTSI KUUKIRI 1924 XVIII AASTAKÄIK & 8 Mõnda Anton Thor Helle elust ja tegevusest. Jüri kirikukroonikas on Anton Thor Hellele võrreldes teistega kõige rohkem ruumi pühendatud. See on ka aru saadav, sest et ta üks neist õpetajaist on olnud, keda jürila- sed veel praegu mäletavad ja kelle teened Piibli tõlkimise alal on, nagu teada, kogu Eestile tuntud. Peale muu kir jutatakse selles kroonikas Anton Thor Hellest järgmist: Anton Thor Helle sünni-kuupäev on teadmata. Ristitud on ta Tallinnas P. Nikolai kirikus 28. oktoobril 1683. aastal. Tema isa on kaupmees Anton Thor Helle, ema Wendela Oom. Ta kuulus Tallinnas elavasse pere konda, kes oma nime vaheldamisi kirjutas Ghor, Thor, zur Helle ja kelle nimi juba aastal 1460 Tallinnas ette tuleb. Pärast gümnaasiumi lõpetamist astus ta septembri kuul 1705 Kiili ülikooli usuteadust õppima. Nimetatud ülikoolis oli ta arvatavasti Tallinna linna stipendiaadina. Abi- "* ellu astus Anton Thor Helle esimest kord 19. juulil 1713. a. Katharina Helene Kniperiga. Viimane oli pastor Toomas Kniperi tütar. Sellest abielust sündis tütar Kristina, kes kirikuõpetaja Gustav Ernst Hasselblatfile mehele läks. Hiljemini leseks jäänud, astus ta uuesti abiellu. Teist kord astus Anton Thor Helle abiellu 20. septembril 1725. a. Maria Elisabeth 01decop'iga, bürgermeister Johan 01decop'i tütrega.