Jin-Ho Park Rudolph M. Schindler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Modernism Without Modernity: the Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Management Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2004 Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F. Guillen University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Guillen, M. F. (2004). Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940. Latin American Research Review, 39 (2), 6-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0032 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers/279 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Abstract : Why did machine-age modernist architecture diffuse to Latin America so quickly after its rise in Continental Europe during the 1910s and 1920s? Why was it a more successful movement in relatively backward Brazil and Mexico than in more affluent and industrialized Argentina? After reviewing the historical development of architectural modernism in these three countries, several explanations are tested against the comparative evidence. Standards of living, industrialization, sociopolitical upheaval, and the absence of working-class consumerism are found to be limited as explanations. As in Europe, Modernism -

Modern Architecture and Luxury: Aesthetics and the Evolution of the Modern Subject

arts Book Review Modern Architecture and Luxury: Aesthetics and the Evolution of the Modern Subject Joanna Merwood-Salisbury School of Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] Received: 30 July 2019; Accepted: 31 July 2019; Published: 6 August 2019 Abstract: A book review of Robin Schuldenfrei, Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900–1933 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018). This book challenges the canonical interpretation of two of the most revered institutions in the history of modern architecture—the Werkbund and the Bauhaus—and presents a critical interpretation of the relationship between modern architecture and luxury, which first appeared a generation ago. Keywords: architecture; design; luxury; AEG; Werkbund; Bauhaus; Germany; modernism Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900–1933 challenges the canonical interpretation of two of the most revered institutions in the history of modern architecture—the Werkbund and the Bauhaus—and presents a critical interpretation of the relationship between modern architecture and luxury, which first appeared a generation ago. In the founding documents of the modern movement, architecture and luxury were framed as irreconcilable opposites. To be modern was to reject ornament—the traditional aesthetic signifier of social status (Veblen [1899] 1994; Sombart [1913] 1967; Massey 2004). Cheapened by thoughtless application, ornament was seen as wasteful and excessive—a superfluous excrescence to be sloughed off through purifying processes of subtraction and elimination. Framed in terms of social evolution, to take pleasure in ornament was evidence of a primitive or retarded stage of racial development (Loos [1908] 1970; Muthesius [1903] 1994). -

Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism As a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union

Momentum Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 6 2018 Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Robert Levine University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum Recommended Citation Levine, Robert (2018) "Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union," Momentum: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Abstract This paper examines the role of architecture in the promotion of political ideologies through the study of modern architecture in the 20th century. First, it historicizes the development of modern architecture and establishes the style as a tool to convey progressive thought; following this perspective, the paper examines Swedish Functionalism and Constructivism in the Soviet Union as two case studies exploring how politicians react to modern architecture and the ideas that it promotes. In Sweden, Modernism’s ideals of moving past “tradition,” embracing modernity, and striving to improve life were in lock step with the folkhemmet, unleashing the nation from its past and ushering it into the future. In the Soviet Union, on the other hand, these ideals represented an ideological threat to Stalin’s totalitarian state. This thesis or dissertation is available in Momentum: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 Levine: Modern Architecture & Ideology Modern Architecture & Ideology Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Robert Levine, University of Pennsylvania C'17 Abstract This paper examines the role of architecture in the promotion of political ideologies through the study of modern architecture in the 20th century. -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center Elizabeth Stoloff Vehse West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Vehse, Elizabeth Stoloff, "Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 848. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/848 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves’s Erickson Alumni Center Elizabeth Stoloff Vehse Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Kristina Olson, M.A., Chair Janet Snyder, Ph.D. -

Modernism in Washington Brochure

MODERNISM IN WASHINGTON MODERNISM IN WASHINGTON The types of resources considered worthy of preservation have continually evolved since the earliest efforts aimed at memorializing the homes of our nation’s founders. In addition to sites associated with individuals or events, buildings and neighborhoods are now looked at not just as monuments to those who lived or worked in them, but as representative expressions of their time. In the past decade, increasing interest and attention has focused on buildings of the relatively recent past, those constructed in the mid-20th century. However, understanding – much less protecting – buildings and sites from the recent past presents several challenges. How do we distinguish which buildings are significant among such an overwhelming representation of a period? How do we appreciate the buildings of an era that often resulted in the destruction of significant 19th and early 20th century buildings, and that have come to be associated with sprawl or failed urban redevelopment experiments? How can we think critically about evaluating and possibly preserving buildings which are simply so … modern? Understanding what Modernism is and what it has meant is an important first step towards recognizing significant or representative buildings. This brochure offers a broad outline of the ideas and trends in the emergence and evolution of Modern design in Washington so that Modernism can be incorporated into discussions of our city’s history, culture, architecture and preservation. INTRODUCTION The term “Modernism” is generally used to describe various 20th century architectural trends that combine functionalism, redefined aesthetics, new technologies, and the rejection of historical precepts. Unlike its immediate predecessors, such as Art Deco and Streamlined Moderne, Modernism in the mid-20th century was not so much an architectural style as it was a flexible concept, adapted and applied in a wide variety of ways. -

Teresa Żarnower: Bodies and Buildings

· TERESA ZARNOWER BODIES AND BUILDINGS By Adrian Anagnost Enlightened peasant: He has a car, a motorcycle, a bicycle / A House of reinforced concrete (Designed by Miss Żarnower) / An Electric kettle, Shiny-cheeked children, A library with thousands of volumes, And a canary that sings the Internationale – Julian Tuwim, 1928 olish artist Teresa Żarnower (1895? –1950) is recognized as belonging to the utopian strand of the interwar avant- Pgardes, those artists, architects, and writers whose works evinced a faith in technology and progress. Writing in the catalogue for the Constructivist-oriented Wystawa Nowej Sztuki (New Art Exhibition), held in the Polish-Lithuanian city of Vilnius in 1923, Żarnower described a new collective “delight” in the “simplicity and logical structure” of machines, “the equivalent of which is located in the simplicity and logic of artworks.” 1 The following year, Żarnower co-founded the Fig. 1. Teresa Żarnower. Untitled (late 1910s), medium and size unknown. Warsaw avant-garde gr oup Blok, active from 1924 through 1926, and she co-edited the group’s journal. Along with the groups Praesens (1926 –30) and a.r. (1929 –36), Blok was one of a Żarnower herself occupied a middle point on this continu - number of avant-garde artistic constellations in interwar um. Though she collaborated on modernist building designs Poland that encompassed Cubist, Suprematist, and with her partner, Mieczysław Szczuka, and with various archi - Constructivist tendencies. 2 What these groups shared was not tects, these designs went unbuilt. 5 But, in contrast to Kobro, her style alone, however, but an investment in architecture as a artistic production was not an essentialist investigation of the guiding principle for aesthetic production. -

Timeline of Residential Architectural Styles in San Francisco 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2016

Timeline of Residential Architectural Styles in San Francisco 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2016 Spanish Eclectic / Mediterranean Revival Art Deco International Style Streamline Moderne Bay Area Modernism: Second Bay Area Style 1923: The Bay Area Modernism: Third Bay Area Style architect Le Corbusier Eichlers publishes his book Towards An Postmodernism Architecture that 1941-1945: WW2 boosts advocates a SF population to a record New Modernism modern 800,000, many stay in SF architecture based after the war on pure function and pure form, not on the past 1929: Stock Market 1933: Rise of Fascism in Crash, start of the Europe, avant-garde 1970s-now: The “Painted Lady” myth heaps more Great Depression architects flee to the US, indignity on SF’s remaining Victorian & Edwardian Mies van der Rohe to Illinois 1960s: Hippies are homes. Self-described “color consultants” deface Institute of Technology, attracted to the buildings with circus wagon paint schemes that Walter Gropius to Harvard cheap rents in the only get worse when exterior grade gold metallic Haight and paint its paint becomes available in the 1990s. 1995–2000: The dotcom bubble, 1918: Streetcar service Victorian & Edwardian Unfortunately, many books are published duping a many lofts built in SOMA through Twin Peaks and homes garish colors well-meaning public to accept this recent myth as to the Sunset 100 year old fact. 1932: Influential exhibition The International Style Since 1922 1966: Architect Robert Venturi rejects 1915: Panama Pacific at New York City International -

Joseph Eichler Sah/Scc Lecture and Tour: Saturday, September 15Th

SAH/SCC TAV. F TA^VE MIST-'--. l^Hl : TA^ F; H ,Vi ITA'i V j^6T^ UyriT^f lRMlJA^ENU-.TA':^UTiUITA-:. 11 F. M I TAi^Y E^tU^iT AjJ^ I T11^ ^ F V-'w W I TA _ I ... I .1- 4-1 .JTW^ITAP f if-Wi A!l\N^A#WriLiTAi; Pipsi-. W. yTTft A N I>#IA FlIRtsJITAS VENUf-.TAt. i-JTILiX&b Fit- . ST A: STAf I KII I JA S II. N iliiJ\.-': TAS VENUSTASi UTI A - J A i C' ^-i^' '-P'- ' ^A- ••' ^ u'ujTA C H A r 1 £ K STA- iHwf AS. IENA'^S RllTAf. VENUSifAS UTI post office box 5 6 4 7 8, Sherman oaks, co 9 1 413 8 0 0.9 SAHSCC www.sahscc.org U.S. Postage O Joseph eich/er lecture and tour FIRST CLASS MAIL O president's letter PAID CN Pasadena, CA Pemiit No. 740 o 4-' iconic la tour pa^3 D events calendar pages 4^5 DO LU O D architectural exhibitions bookmarks page 7 >^ CN The living room area and outdoor view of (he Eichler Home in the Fair Haven development in the city of Orange. (Photo. John Berky) MODERNISM FOR THE MASSES: JOSEPH EICHLER SAH/SCC LECTURE AND TOUR: SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 15TH Moreover, Eichler Please join the SAH/SCC for a rare opportunity to Homes were marketed learn alDOut and experience visionary developer not merely as Joseph Eichler's residential communities for residences, but as a modern living. Modernism for the Masses will "New Way of Life." be held on Saturday, September 15th, in the city In recent years, of Orange. -

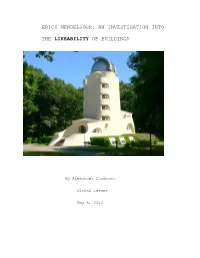

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level). -

S I M ~ L E Luxuries & Seamless Living: the Legacy of the Eichler Homes

i 14 LEGACY + ASPIRATIONS Sim~le- Luxuries ------- - - - &-- Seamless- - ------ - - - Living: The Legacy of the Eichler Homes HERBERT ENNS (Editor) RAFAEL GOMEZ-MORIANA University of Manitoba University of Manitoba KEVIN ALTER SHIRLEY MADILL University of Texas at Austin Winnipeg Art Gallery INTRODUCTION The orthodox principles of modern space and the employ of universal techniques of mass production are appropriated to accom- ...I have been thinking about the cloudburst of new houses modate local exigencies. They define a Californian modernism - as which as soon as the war is ended is going to cover the hills initiated by John Entenza and his Art and Architecture Case-Study and valleys of New England with so many square miles of program. Although intended as a prototypical projects, the Case- prefabricated happiness.' Stlcdj program never grew beyond a series of "one-off" buildings. -Joseph Hudnut, 1945 The Eichlers Homes, on the other hand, offered mass housing for the The 1950s witnessed a coming together of many areas in contempo- middle class. rary life. Industrial growth and prosperity launched an optimistic Joe Eichler was not an architect; he was a developer. The archi- mass culture energized by the experiments of the early modernists tects he hired to design his homes, while significant, were not the and fortified by universal demands for a new improved world. A preeminent architects of their day. Although their proposition was mature modernism, confident of popular appeal, developed rapidly radical in the context of merchant building - and indeed they were in all areas of art, design and architecture. This movement was ridiculed by their competition - it was a very successful architec- eagerly expansiveinitsexploitation ofnew forms and processes, and tural and financial program. -

History of Architecture : Modern Architecture

HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE : MODERN ARCHITECTURE SEM.: 5TH Characteristics of modern architecture • A rejection of historical styles as a source of architectural form (historicism) • An adoption of the principle that the materials and functional requirements determine the result • An adoption of the machine aesthetic • A rejection of ornament • A simplification of form and elimination of "unnecessary detail" • An adoption of expressed structure • Form follows function Modern concepts of architecture The great 19th century architect of To restrict the meaning of (architectural) formalism to art skyscrapers, Louis Sullivan, promoted an for art's sake is not only reactionary; it can also be a purposeless quest for perfection or originality which overriding precept to architectural design: degrades form into a mere instrumentality“. "Form follows function". Ivar Holm points out that the values and attitudes which While the notion that structural and underly modern architecture differ both between the aesthetic considerations should be entirely schools of thought which influence architecture and between individual practising architects. subject to functionality was met with both popularity and scepticism, it had the effect Among the philosophies that have influenced modern architects and their approach to building design are of introducing the concept of "function" in rationalism, empiricism, structuralism, poststructuralism, place of Vitruvius "utility". and phenomenology. "Function" came to be seen as In the late 20th century a new concept was added to encompassing all criteria of the use, those included in the compass of both structure and function, the consideration of sustainability. perception and enjoyment of a building, To satisfy the modern ethos a building should be not only practical but also aesthetic, constructed in a manner which is environmentally psychological and cultural.