Copyright by Christopher Haviland Ketcham 2010 the Dissertation Committee for Christopher Haviland Ketcham Certifies That This Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

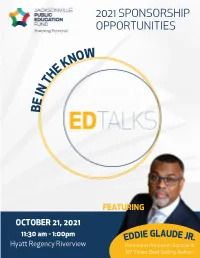

2021 Edtalks Sponsorship Packet

2021 SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES OW KN E H T N I E B FEATURING OCTOBER 21, 2021 11:30 am - 1:00pm EDDIE GLAUDE JR. Hyatt Regency Riverview Prominent Princeton Scholar & NY Times Best Selling Author Children are our greatest resource, and the best gift we can give them is a quality education. BE AT THE FOREFRONT OF EDUCATION INNOVATION The Jacksonville Public Education Fund is an independent think-and-do tank that believes in the potential of all students. We work tirelessly to close the opportunity gap for low-income students and students of color in Duval County. We convene educators, school system leaders and the community to pilot and scale evidence-based solutions that advance school quality in Duval County. BE IN THE KNOW: EDTALKS EDTalks is a biennial convening designed to bring thought leaders in education to spark action and innovation in Duval County. EDTalks inspires education leaders and partners to take collective action on best practices in school quality. This year’s event will feature Eddie Glaude Jr., one of the nation’s most prominent scholars. Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. is a NY Times best-selling author, Princeton scholar, public intellectual, and passionate educator. Glaude is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and Chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton. He frequently appears in the media as a columnist for TIME Magazine, MSNBC contributor, and many other platforms to discuss topics such as diversity and equity in education and America. EDTalks 2021 will inspire local educators and community partners to close the opportunity gap between low-income students, students of color, and their peers as we launch new strategies for Duval County. -

Programs & Exhibitions

PROGRAMS & EXHIBITIONS Fall 2018/Winter 2019 To purchase tickets by phone call (212) 485-9268 letter | exhibitions | calendar | programs | family | membership | general information Dear Friends, History Matters has long been New-York Historical’s motto, but if ever there were a time when this motto rang particularly true, it would be our launch this fall of two landmark exhibitions. The first,Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow, takes as its starting point the terrible injustice of the Supreme Court ruling in the Dred Scott case that no black person— free or enslaved—could ever be a U.S. citizen. The exhibition traces the story of African Americans’ struggle for citizenship, including not only the right to enjoy legal protections and privileges but also the right to be accepted and to feel safe. The second exhibition, Harry Potter: A History of Magic, draws on the global phenomenon of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels while dramatizing the historical context indispensable to the books’ success. Both exhibitions underscore the importance of institutions like ours, whose great repositories enable a better understanding of the past as they illuminate the present. Reflecting these exhibitions’ themes, our Bernard and Irene Schwartz Distinguished Speakers Series features discussions of citizenship, race, history, and law, with speakers including Eric Foner, Harold Holzer, U.S. Senator Doug Jones, Martha Jones, Randall Kennedy, Edna Greene Medford, Manisha Sinha, Brent Staples, and Sean Wilentz. The Mathew “Mike” Gladstein Lecture in Biography features New-York Historical Trustee David Blight in conversation with Eddie Glaude Jr. on Frederick Douglass. For Harry Potter, our Schwartz Series features Jim Dale, the narrator and voice of all of the Harry Potter characters in the American audiobooks. -

The Critic's Choice

The Critic's Choice Book Review Begin Again. James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own By Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. Crown Publishers New York 2020 Christine Nava, MS Former President, Escondido Chamber of Citizens Civic Leader for Social Justice & Human Rights San Diego, CA Tel: (760) 715-9053 Email: [email protected] Author Note The release of Begin Again in June 2020 was met with acclamation from critics throughout the country, including scholars, historians, political leaders, and giants in the Black struggle. This reviewer is not among this distinguished group of critics. I am a lay person--an ordinary woman on the street--whose life of activism began as a member of a religious community when, in 1965, I joined a group of Catholic sisters from St. Louis and travelled to Selma to protest at the Selma Voting Rights March. The event had a profound effect on my life that remains to this day. In my “after life” since I left religious community, I raised a family, taught, joined civic organizations, lobbied members of congress and local elected officials on social justice issues, never forgetting the importance of bearing witness--the lessons of Selma. Introduction My work on this book began with James Baldwin’s words, “You must understand that your pain is trivial except insofar as you can use it to connect other people’s pain, and insofar as you can do that with your pain, you can be released from it, and then hopefully it works the other way around too; insofar as I can tell you what it is to suffer, perhaps I can help you to suffer less.” — Begin Again, p. -

Annual Report

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Prof. Griffith, Center Director, teaches a small seminar class. ABOUT THE COVER: Sen. Jack Danforth and Prof. Amy Chua discuss her recent book in a public conversation hosted in Washington University’s Graham Chapel. MISSION The Center serves as an open venue for fostering rigorous scholarship and informing broad academic and public communities about the intersections of religion and U.S. politics. PG 2 PG 4 PG 6 PG 12 PG 26 PG 45 AT A GLANCE LETTERS RESEARCH AND PUBLIC PEOPLE LOOKING TEACHING ENGAGEMENT FORWARD 1 John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics 2019-2020 Annual Report 2019-2020 AT A GLANCE The John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics is a dynamic academic center with many different activities and community interactions happening each day. While we can’t tell a full story with numbers, a snapshot can give a sense of this year’s accomplishments. 14 48 UNDERGRADUATE ARTICLES PUBLISHED COURSES in Religion & Politics OFFERED IN 2019-2020 IN 2019-2020 12 2000+ 11 PUBLIC EVENTS ATTENDEES AT MEETINGS OF THE SUPPORTED BY PUBLIC EVENTS COLLOQUIUM THE CENTER IN 2019-2020 ON AMERICAN RELIGION, POLITICS, AND CULTURE 34 8 STUDENTS WITH FACULTY A DECLARED MINOR MEMBERS IN RELIGION AND POLITICS 2 Umrath Hall is home to the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics. 3 LETTER FROM THE CHANCELLOR What a year it has been! In fact, I’d venture to say this past academic year was filled with some of the most pressing political and ethical challenges of our time, one of the most significant being our community and global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. -

WEEKLY Church March 15 - 21, 2020

White Bear THE NEWS Unitarian Universalist WEEKLY Church March 15 - 21, 2020 328 Maple Street | Mahtomedi, MN 55115 | Phone: 651.426.2369 | wbuuc.org CORONAVIRUS UPDATE We are carefully watching updates from the MN Dept. of Health, local school districts, and other sources, and we are committed to best practices for individual and community wellness. Let’s stay healthy by refraining for now from handshakes and hugs here at church. A warm and friendly smile will welcome visitors wholeheartedly, and greet old friends just fi ne. Many in our community are holding concerns not only about the virus itself, but about travel, work, sick leave, childcare and more. As ever, our Pastoral Care team, RE staff, and ministers are available for support in these uncertain times. Stay Safe! If you are sick, stay home. Let us know and we will reach out to you. ~ Rev. Victoria Safford, [email protected], 651.426.2369 x101 FACING RACE UPDATE EARTH MINISTRY UPDATE Westminster Forum Ice Out—Coming Soon to a Lake Near You Tuesday, May 12 at 12pm A sure sign of spring is open water on lakes. Data Eddie Glaude, Jr.: James Baldwin’s (1950 to present) tells us to expect ice out of Lessons on Race in America area lakes during the fi rst week of April (yellow Westminster Presbyterian Church points on the map). Minnesota ice out dates in 1200 Marquette Ave, Minneapolis other regions vary between May 5 (dark pink) and Eddie Glaude, Jr. is a Professor at Princeton March 25 (orange points). University and chair of the Department of African Ice melt is effected by the jet stream’s infl uence American Studies. -

Melvin L. Rogers Department of Political Science Brown University 111 Thayer

MELVIN L. ROGERS DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BROWN UNIVERSITY 111 THAYER STREET PROVIDENCE, RI 02912 [email protected] HTTPS://VIVO.BROWN.EDU/DISPLAY/MROGERS4 HTTPS://WWW.MELVINROGERS.SITE TWITTER: @MROGERS097 ACADEMIC POSITION Brown University, Providence, RI Associate Professor of Political Science, July, 2017- Faculty Affiliate in Africana Studies, October, 2017- PREVIOUS POSITIONS University of California, Los Angeles Scott Waugh Chair in the Division of the Social Sciences, July, 2015-July 2017 Associate Professor, African American Studies and Political Science, July, 2014-July, 2017 (Currently 50% African American Studies/50% Political Science) Emory University, Atlanta, GA Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, August, 2012-August, 2014 Faculty Associate, Department of Political Science, September, 2012-August, 2014 University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, 2007-2012 Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, 2010-11 Carleton College, Northfield, MN Scholar-In-Residence, Department of Political Science, 2005-2007 EDUCATION Yale University, New Haven, CT Ph.D., Political Science, with Distinction, December 2006 M.Phil., Political Science, May, 2004 Princeton University, Princeton, NJ Exchange Scholar, Department of Religion, 2004-2005 University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England M.Phil., Political Thought and Intellectual History, 2000 Amherst College, Amherst, MA B.A., Political Science, magna cum laude, Phi Beta -

Princeton University Bulletin, Oct. 12, 2009

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY BULLETINVolume 99, Number 3 October 12, 2009 Setting the path for the study of race Center for African American Studies poised to lead at critical time CASS CLIATT rinceton’s Center for African American Studies is launching an P aggressive effort to become the leading resource for the public’s under- standing of race in America, coming at a time when the center’s scholars say they are seeing an upward trend in racial issues igniting the country in a series of “brush fires.” Working with a new chair, scholars will build on growth and strategies developed in the center’s first three years to take advantage of fresh avenues to broaden discussions of race with the public, to engage in research that could be of use to policymakers, and to har- ness a unique interdisciplinary approach to reach the next generation of leaders. “When we begin to think about the direction of the field, we believe that Denise Applewhite Brian Wilson Denise Applewhite what we’re doing here at Princeton, Princeton’s Center for African American Studies, led by chair Eddie Glaude (left), brings pioneers in the field together with rising scholars such as right here in this moment, will set the Wendy Belcher (center) and Imani Perry (right) in an effort to become the pre-eminent resource for the public’s understanding of race in America. path for the field of African American studies in the next century,” said new center chair Eddie Glaude, Princeton’s a pool at a Philadelphia swim club in debate between leading academics in citizenship, “tea parties” to protest William S. -

Princeton's Eddie Glaude Jr. to Keynote

www.mississippilink.com VOL. 26, NO. 18 FEBRUARY 20 - 26, 2020 50¢ Alcorn State University Statement Holmes County 6th-graders on off-campus shooting experience HOPE; ASU mourns the passing of students other grades targeted James Carr and Tahir Fitzhugh Special to The Mississippi Link The Community Students Alcorn State University Learning Center (CSLC), in Public Relations partnership with the Holmes Statement from the Offi ce of County Consolidated School Alcorn Public Relations District and other key part- Overnight Monday, Feb. 17, ners, is implementing HOPE Alcorn State University was noti- (Health Optimization and Pre- fi ed by local authorities that four vention Education). of our students were involved in The CSLC HOPE program a shooting that occurred at a non- offers a healthy relationship life goals. university event venue 13 miles evidenced-based curriculum to With informed parental con- north of campus off Highway 61 the students of Holmes County sent, sixth-graders at S.V. Mar- in Claiborne County. titled Love Notes, Life and shall and Williams-Sullivan Three of the students were Work by Dibble’s Institute. A middle schools were the fi rst transported to the Claiborne program of the U.S. Depart- to complete the 13-lesson ses- County Medical Center in Port ment of Health and Human sions last semester just prior to Gibson. We are deeply saddened Services Offi ce of Population the holidays. to report that two students have Affairs (OPA), TPP19, HOPE “My son really benefi t- passed as a result of critical in- targets youth in 6th-12th ted from HOPE,” said parent, juries suffered in the shooting. -

Cornel R West 2012 Book.Pdf

Princeton University Honors Faculty Members Receiving Emeritus Status May 2012 The biographical sketches were written by colleagues in the departments of those honored. Copyright © 2012 by The Trustees of Princeton University 26763-12 Contents Faculty Members Receiving Emeritus Status Larry Martin Bartels 3 James Riley Broach 5 William Browder 8 Lawrence Neil Danson 11 John McConnon Darley 16 Philip Nicholas Johnson-Laird 19 Seiichi Makino 22 Hugo Meyer 25 Jeremiah P. Ostriker 27 Elias M. Stein 30 Cornel R. West 32 Cornel R. West This spring, Cornel West retires as the Class of 1943 University Professor in the Center for African American Studies at Princeton University, and joins the illustrious ranks of our professors emeriti. For nearly 40 years, Cornel has had a deep and abiding relationship with Princeton, and we celebrate his enormous contribution to the Princeton community, and to the world at large. Cornel was born on June 2, 1953, in Tulsa, Okla., the grandson of the Reverend Clifton L. West Sr., pastor of the Tulsa Metropolitan Baptist Church. Cornel’s mother, Irene Bias West, was an elementary school teacher (and later principal), while his father, Clifton L. West Jr., was a civilian Air Force administrator. From his parents, siblings and community, young Cornel derived “ideals and images of dignity, integrity, majesty and humility.” These values, he has written, provided him “existential and ethical equipment to confront the crises, terrors and horrors of life.” He completed his undergraduate education at Harvard University in 1973, where he graduated magna cum laude after three years and received a B.A. -

"I'm Concerned If We Don't Impeach This President, He Will Get Re-Elected"

12/14/19, 1007 PM Page 1 of 1 Back to Videos Rep. Al Green: "I'm Concerned If We Don't Impeach This President, He Will Get Re-Elected" Posted By Tim Hains On Date May 6, 2019 Rep. Al Green: "I'm Concerned If We … Rep. Al Green told MSNBC Saturday that he is "concerned if we don’t impeach this president, he will get re-elected." "As I look the people of America in the eye, I’m telling you, we have a constitutional crisis," Green said. "We must impeach this president. If you don’t, it’s not the soul of the nation that will be at risk only, it is the soul of the Congress that’s at risk." PRESIDENT TRUMP, 16 JULY 2018: I have President Putin, he just said it's not Russia. I will say this, I don't see any reason why it would be. I have great confdence in my intelligence people, but I will tell you that President Putin is extremely strong and powerful in his denial today. MSNBC HOST: Congressman, how do you interpret President Trump not telling Vladimir Putin to stay out of our next election? REP. AL GREEN: I see this as unconscionable, it's inconceivable. One can only imagine what it does to the esprit de corps of the persons who work in our intelligence agencies. They have said the Russians interfered. Mr. Mueller has said the Russians interfered. The president has not, and he talks about a great relationship between Mr. Putin and Russia. -

Eddie S. Glaude Jr

Eddie S. Glaude Jr. Eddie S. Glaude Jr. is an intellectual who speaks to the complex dynamics of the American experience. His most well -known books, Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul, and In a Shade of Blue: Pragmatism and the Politics of Black America, take a wide look at black communities, the difficulties of race in the United States, and the challenges our democracy face. He is an American critic in the tradition of James Baldwin and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In his writings, the country’s complexities, vulnerabilities, and the opportunities for hope come into full view. Hope that is, in one of his favorite quotes from W.E.B Du Bois, “not hopeless, but a bit unhopeful.” He is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and chair of the Department of African American Studies, a program he first became involved with shaping as a doctoral candidate in Religion at Princeton. He is the former president of the American Academy of Religion. His books on religion and philosophy include An Uncommon Faith: A Pragmatic Approach to the Study of African American Religion, African American Religion: A Very Short Introduction and Exodus! Religion, Race and Nation in Early 19th Century Black America, which was awarded the Modern Language Association’s William Sanders Scarborough Book Prize. Glaude is also the author of two edited volumes, and many influential articles about religion for academic journals. He has also written for the likes of The New York Times and Time Magazine. Known to be a convener of conversations and debates, Glaude takes care to engage fellow citizens of all ages and backgrounds – from young activists, to fellow academics, journalists and commentators, and followers on Twitter in dialogue about the direction of the nation. -

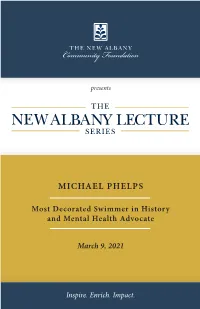

Michael Phelps

presents MICHAEL PHELPS Most Decorated Swimmer in History and Mental Health Advocate March 9, 2021 Inspire. Enrich. Impact. An evening with MICHAEL PHELPS WELCOME JANELLE COLEMAN President, AEP Foundation Vice President, Corporate & Community Engagement PROGRAM MICHAEL PHELPS Most Decorated Swimmer in History and Mental Health Advocate Interviewed by DOUG ULMAN President & Chief Executive Officer, Pelotonia AUDIENCE QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Thank you to our sponsors of this evening’s New Albany Lecture Series program Special Program Underwriters The Barbara W. & Philip R. Derrow Family Foundation Season Sponsors Conway Charitable Lead Annuity Trust Beatrice Wolper, Trustee The New Albany Lecture Series Endowment Fund Supporters Donna & Nick Akins Fund Redgrave Family Fund Archer Family Fund Ryan Family Fund Karen & Irving Dennis Family Fund Lynne & Steve Smith Family Fund Ben W. Hale Jr. Memorial Fund Leslie H. Wexner New Albany Lecture Series Fund OUR VISION Speaker Sponsors Healthcare Speaker Sponsor To be the highest value provider of Anonymous Donors global construction services and technical expertise. Community Partners Premier Sponsors www.turnerconstruction.com/columbus 614.984.3000 Dear Friends, Tonight marks the fifth lecture as part of the 2020-2021 New Albany Lecture Series Season. Despite the pandemic, we have managed to reach even more students and residents through the virtual format this season. In fact, we have surpassed 18,000 area students who have participated in the student lecture series. It’s a milestone for which we are extremely proud and we are grateful to all of the schools across central Ohio who make those opportunities available to their students. Based on feedback from those who have participated in the previous four lectures, it has been an outstanding season thus far.