Read Full Penumbra Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

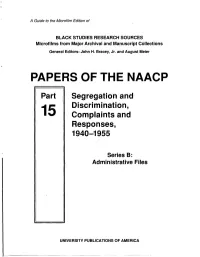

PAPERS of the NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloglng-ln-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial--[etc.]--pt. 15. Segregation and discrimination, complaints and responses, 1940-1955. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People-Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century-Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations-Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- . -

The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class

The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class William P. Jones The very decade which has witnessed the decline of legal Jim Crow has also seen the rise of de facto segregation in our most fundamental socioeconomic institutions,” vet- eran civil rights activist Bayard Rustin wrote in 1965, pointing out that black work- ers were more likely to be unemployed, earn low wages, work in “jobs vulnerable to automation,” and live in impoverished ghettos than when the U.S. Supreme Court banned legal segregation in 1954. Historians have attributed that divergence to a nar- rowing of African American political objectives during the 1950s and early 1960s, away from demands for employment and economic reform that had dominated the agendas of civil rights organizations in the 1940s and later regained urgency in the late 1960s. Jacquelyn Dowd Hall and other scholars emphasize the negative effects of the Cold War, arguing that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other civil rights organizations responded to domestic anticom- munism by distancing themselves from organized labor and the Left and by focusing on racial rather than economic forms of inequality. Manfred Berg and Adam Fair- clough offer the more positive assessment that focusing on racial equality allowed civil rights activists to appropriate the democratic rhetoric of anticommunism and solidify alliances with white liberals during the Cold War, although they agree that “anti- communist hysteria retarded the struggle for racial justice and narrowed the political Research for this article was supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities/Newhouse Fellowship at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Graduate School at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. -

Teaching the March on Washington

Nearly a quarter-million people descended on the nation’s capital for the 1963 March on Washington. As the signs on the opposite page remind us, the march was not only for civil rights but also for jobs and freedom. Bottom left: Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the historic event, stands with marchers. Bottom right: A. Philip Randolph, the architect of the march, links arms with Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers and the most prominent white labor leader to endorse the march. Teaching the March on Washington O n August 28, 1963, the March on Washington captivated the nation’s attention. Nearly a quarter-million people—African Americans and whites, Christians and Jews, along with those of other races and creeds— gathered in the nation’s capital. They came from across the country to demand equal rights and civil rights, social justice and economic justice, and an end to exploitation and discrimination. After all, the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” was the march’s official name, though with the passage of time, “for Jobs and Freedom” has tended to fade. ; The march was the brainchild of longtime labor leader A. PhilipR andolph, and was organized by Bayard RINGER Rustin, a charismatic civil rights activist. Together, they orchestrated the largest nonviolent, mass protest T in American history. It was a day full of songs and speeches, the most famous of which Martin Luther King : AFP/S Jr. delivered in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. top 23, 23, GE Last month marked the 50th anniversary of the march. -

Women's March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity

Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Originally posted on the blog of The American Prospect, January 6, 2017. Confederacy” By Laurie Green For those who believe Donald Trump’s election has further legitimized hatred and even violence, a “Women’s March on Washington” scheduled for January 21 offers an outlet to demonstrate mass solidarity across lines of race, religion, age, gender, national identity, and sexual orientation. May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (The Center for Jewish History via Flickr) The idea of such a march first ricocheted across social media just hours after the TV networks called the DIGITAL HISTORY election for Trump, when a grandmother in Hawaii suggested it to fellow Facebook friends on the private, pro-Hillary Clinton group page known as Pantsuit Nation. Millions of postings later, the D.C. march has mushroomed to include parallel events in 41 states and 21 cities outside the United States. An Más de 72: Digital Archive Review independent national organizing committee has stepped in to articulate a clear mission and take over https://notevenpast.org/womens-march-like-many-before-it-struggles-for-unity/[6/19/2020 8:58:41 AM] Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity - Not Even Past logistics. -

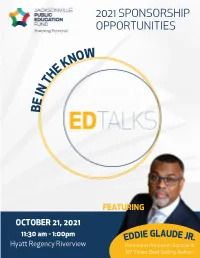

2021 Edtalks Sponsorship Packet

2021 SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES OW KN E H T N I E B FEATURING OCTOBER 21, 2021 11:30 am - 1:00pm EDDIE GLAUDE JR. Hyatt Regency Riverview Prominent Princeton Scholar & NY Times Best Selling Author Children are our greatest resource, and the best gift we can give them is a quality education. BE AT THE FOREFRONT OF EDUCATION INNOVATION The Jacksonville Public Education Fund is an independent think-and-do tank that believes in the potential of all students. We work tirelessly to close the opportunity gap for low-income students and students of color in Duval County. We convene educators, school system leaders and the community to pilot and scale evidence-based solutions that advance school quality in Duval County. BE IN THE KNOW: EDTALKS EDTalks is a biennial convening designed to bring thought leaders in education to spark action and innovation in Duval County. EDTalks inspires education leaders and partners to take collective action on best practices in school quality. This year’s event will feature Eddie Glaude Jr., one of the nation’s most prominent scholars. Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. is a NY Times best-selling author, Princeton scholar, public intellectual, and passionate educator. Glaude is the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and Chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton. He frequently appears in the media as a columnist for TIME Magazine, MSNBC contributor, and many other platforms to discuss topics such as diversity and equity in education and America. EDTalks 2021 will inspire local educators and community partners to close the opportunity gap between low-income students, students of color, and their peers as we launch new strategies for Duval County. -

Programs & Exhibitions

PROGRAMS & EXHIBITIONS Fall 2018/Winter 2019 To purchase tickets by phone call (212) 485-9268 letter | exhibitions | calendar | programs | family | membership | general information Dear Friends, History Matters has long been New-York Historical’s motto, but if ever there were a time when this motto rang particularly true, it would be our launch this fall of two landmark exhibitions. The first,Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow, takes as its starting point the terrible injustice of the Supreme Court ruling in the Dred Scott case that no black person— free or enslaved—could ever be a U.S. citizen. The exhibition traces the story of African Americans’ struggle for citizenship, including not only the right to enjoy legal protections and privileges but also the right to be accepted and to feel safe. The second exhibition, Harry Potter: A History of Magic, draws on the global phenomenon of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels while dramatizing the historical context indispensable to the books’ success. Both exhibitions underscore the importance of institutions like ours, whose great repositories enable a better understanding of the past as they illuminate the present. Reflecting these exhibitions’ themes, our Bernard and Irene Schwartz Distinguished Speakers Series features discussions of citizenship, race, history, and law, with speakers including Eric Foner, Harold Holzer, U.S. Senator Doug Jones, Martha Jones, Randall Kennedy, Edna Greene Medford, Manisha Sinha, Brent Staples, and Sean Wilentz. The Mathew “Mike” Gladstein Lecture in Biography features New-York Historical Trustee David Blight in conversation with Eddie Glaude Jr. on Frederick Douglass. For Harry Potter, our Schwartz Series features Jim Dale, the narrator and voice of all of the Harry Potter characters in the American audiobooks. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced individual views toward women one of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

Copyright by Christopher Haviland Ketcham 2010 the Dissertation Committee for Christopher Haviland Ketcham Certifies That This Is

Copyright by Christopher Haviland Ketcham 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Christopher Haviland Ketcham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: WHAT AND HOW WILL WE TEACH; FOR WHAT SHALL WE TEACH AND WHY? AIMS-TALK IN THE JOURNAL OF NEGRO EDUCATION 1932-1953 Committee: ____________________________ Sherry Field, Supervisor ____________________________ Anthony Brown, Supervisor ____________________________ Lisa J. Cary ____________________________ Norvell Northcutt ____________________________ Mary Lee Webeck WHAT AND HOW WILL WE TEACH; FOR WHAT SHALL WE TEACH AND WHY? AIMS-TALK IN THE JOURNAL OF NEGRO EDUCATION 1932-1953 by Christopher Haviland Ketcham, B. S.; M. B. A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of: Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2010 Epigraph Whence all this passion towards conformity anyway?—diversity is the word. Let man keep his many parts and you‘ll have no tyrant states. Why, if they follow this conformity business they‘ll end up forcing me, an invisible man, to become white, which is not a color but the lack of one. Must I strive towards colorlessness? But seriously, and without snobbery, think of what the world would lose if this should happen. America is woven of many strands; I would recognize them and let it so remain. It is ―winner take nothing‖ that is the great truth of our country or of any country. Life is to be lived, not controlled; and humanity is won by continuing to play in the face of certain defeat. -

The Critic's Choice

The Critic's Choice Book Review Begin Again. James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own By Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. Crown Publishers New York 2020 Christine Nava, MS Former President, Escondido Chamber of Citizens Civic Leader for Social Justice & Human Rights San Diego, CA Tel: (760) 715-9053 Email: [email protected] Author Note The release of Begin Again in June 2020 was met with acclamation from critics throughout the country, including scholars, historians, political leaders, and giants in the Black struggle. This reviewer is not among this distinguished group of critics. I am a lay person--an ordinary woman on the street--whose life of activism began as a member of a religious community when, in 1965, I joined a group of Catholic sisters from St. Louis and travelled to Selma to protest at the Selma Voting Rights March. The event had a profound effect on my life that remains to this day. In my “after life” since I left religious community, I raised a family, taught, joined civic organizations, lobbied members of congress and local elected officials on social justice issues, never forgetting the importance of bearing witness--the lessons of Selma. Introduction My work on this book began with James Baldwin’s words, “You must understand that your pain is trivial except insofar as you can use it to connect other people’s pain, and insofar as you can do that with your pain, you can be released from it, and then hopefully it works the other way around too; insofar as I can tell you what it is to suffer, perhaps I can help you to suffer less.” — Begin Again, p. -

The National Council of Negro Women, Emerging Africa, and Transnational Solidarity, 1935-1966

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “All The Women Are Meeting:” The National Council of Negro Women, Emerging Africa, and Transnational Solidarity, 1935-1966 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Yatta Winnie Kiazolu 2020 © Copyright by Yatta Winnie Kiazolu 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “All The Women Are Meeting:” The National Council of Negro Women, Emerging Africa, and Transnational Solidarity, 1935-1966 by Yatta Kiazolu Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Brenda Stevenson, Chair In the postwar period, the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), the largest African American women’s organization in the United States, positioned themselves as representatives of Black women’s interests on the world stage. Previous studies of founder Mary McLeod Bethune’s internationalism has highlighted her prominent role in this arena primarily through the United Nations, as well as the ways NCNW carried this legacy through their efforts to build relationships with women across the diaspora. But beyond highlighting their activism and the connections they made, the substance and meaning of these relationships as the Cold War and African independence introduced new political terrain has been underexplored. Africa’s prominence on the world stage by the late 1950s reinvigorated the need for Black diaspora activists to strengthen their relationships on the continent. Toward this end, NCNW leaders such Dorothy Ferebee, Vivian Mason, Dorothy Height forged connections with their counterparts across the Atlantic. African women such as Ghana’s Mabel Dove and Evelyn ii Amarteifio, Tanzania’s Lucy Lameck, among numerous others played critical roles within their respective independence movements. -

Annual Report

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Prof. Griffith, Center Director, teaches a small seminar class. ABOUT THE COVER: Sen. Jack Danforth and Prof. Amy Chua discuss her recent book in a public conversation hosted in Washington University’s Graham Chapel. MISSION The Center serves as an open venue for fostering rigorous scholarship and informing broad academic and public communities about the intersections of religion and U.S. politics. PG 2 PG 4 PG 6 PG 12 PG 26 PG 45 AT A GLANCE LETTERS RESEARCH AND PUBLIC PEOPLE LOOKING TEACHING ENGAGEMENT FORWARD 1 John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics 2019-2020 Annual Report 2019-2020 AT A GLANCE The John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics is a dynamic academic center with many different activities and community interactions happening each day. While we can’t tell a full story with numbers, a snapshot can give a sense of this year’s accomplishments. 14 48 UNDERGRADUATE ARTICLES PUBLISHED COURSES in Religion & Politics OFFERED IN 2019-2020 IN 2019-2020 12 2000+ 11 PUBLIC EVENTS ATTENDEES AT MEETINGS OF THE SUPPORTED BY PUBLIC EVENTS COLLOQUIUM THE CENTER IN 2019-2020 ON AMERICAN RELIGION, POLITICS, AND CULTURE 34 8 STUDENTS WITH FACULTY A DECLARED MINOR MEMBERS IN RELIGION AND POLITICS 2 Umrath Hall is home to the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics. 3 LETTER FROM THE CHANCELLOR What a year it has been! In fact, I’d venture to say this past academic year was filled with some of the most pressing political and ethical challenges of our time, one of the most significant being our community and global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. -

2015 Hedgeman Center Brochure.Booklet Form.Final.Pub

THE HEDGEMAN CENTER for Student Diversity Initiatives and Programs The Hedgeman Center for Student Diversity Initiatives and Programs helps create and sustain an inclusive community that appreciates, celebrates and advances student and campus diversity at Hamline University. We support, empower, and promote the success of students with particular attention to students of color first generation college students and others from historically marginalized backgrounds. In partnership with other university and community members, we help prepare students to live, serve and succeed in a diverse university and world. We Help Prepare Students to Live, Serve and Succeed By: Providing personal, social, and cultural advising, support and advocacy for students. Offering services, resources and initiatives that assist students with full engagement and participation in college life, including a successful transitions from matriculation to graduation. Assisting students and student organizations with leadership development that facilitates their active engagement and participation in the university. Partnering, collaborating and consulting with other departments to create environments supportive of students’ interests, needs, concerns, issues and experiences. Developing and implementing diversity workshops, programs and training opportunities. Collaborating on the planning, coordination and celebration of traditional cultural and awareness events. Assisting with the coordination, staffing, training and program implementation of the Hamline team of administrators, faculty, staff, and students that attends the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity. 2014 Undergraduate Student Demographics: American Indian/ Native American - <1% Asian American Students - 6% Multi-racial/ Biracial - 6% Black American Students - 6% International Students - 1% Hispanic/ Latino Students - 6% First-Generation College Students - 33% Hamline University www.hamline.edu/hedgeman 1536 Hewitt Avenue (651) 523-2423 St.