Davitashvili Et Al. V. Grubhub Inc. Et

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMO170129 Delivery Whitepaper

THE REVENUE ENGINE 5 Factors Fueling the Takeoff of Delivery & Takeout Fasten your menus! More and more restaurants are jumpstarting business with help from takeout and delivery services. From a trickle of dine-in foot traffic to the fast lane of to-go orders, sales are picking up speed thanks to this turbo-charged trend. 1. ACCELERATING DEMAND A decline in foot traffic for 6 quarters in a row has compelled Drawn to its easy accessibility and convenient meal solutions, restaurants to find a way to turn the corner on customer millennials in particular are driving the delivery and takeout acquisition and retention. Takeout and delivery have proven trend to new heights. On the mark for their on-the-go to be a reliable road to increased sales, exponentially lifestyles, delivery and takeout meet the millennial need for expanding the reach of restaurants and allowing them to speed, as technology streamlines the order and payment accommodate even more customers than their dining rooms process and removes the roadblock of human interaction. can accommodate. QUICK BITE: Chains like Papa John’s and Domino’s that excel at delivery are RUNNING pulling ahead in sales.1 THE NUMBERS average rate at which estimated value of $ 5X consumers surveyed 2016 global food 114 2 /mo. purchase takeout1 billion delivery market of consumers surveyed order more often % purchase takeout 10x % from fast casual 1 19 per month 49 restaurants1 order fast food of all restaurant visits % to-go more % consisted of to-go 79 often1 61 orders in 20163 DID YOU KNOW? Pizza Hut is grabbing a bigger slice of the delivery and takeout pie. -

The Promise of Platform Work: Understanding the Ecosystem

Platform for Shaping the Future of the New Economy and Society The Promise of Platform Work: Understanding the Ecosystem January 2020 This white paper is produced by the World Economic Forum’s Platform for Shaping the Future of the New Economy and Society as part of its Promise of Platform Work project, which is working with digital work/services platforms to create strong principles for the quality of the work that they facilitate. It accompanies the Charter of Principles for Good Platform Work. Understanding of the platform economy has been held back by two key issues: lack of definitional clarity and lack of data. This white paper focuses on definitional issues, in line with the objectives of our Platform Work project. It maps the different categories of digital work/service platform and the business-model-specific and cross-cutting opportunities and challenges they pose for workers. It is designed to help policymakers and other stakeholders be more informed about such platforms and about the people using them to work; to support constructive and balanced debate; to aid the design of effective solutions; and to help established digital work/services platforms, labour organisations and others to build alliances. While this paper provides some data for illustrative purposes, providing deeper and more extensive data to close the gaps in the understanding of the platform economy is beyond the current scope of this project. We welcome multistakeholder collaboration between international organisations, national statistical agencies and digital work/services platforms to create new metrics on the size and distribution of the platform economy. This report has been published by the World Economic Forum. -

YELP INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 OR ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number: 001-35444 YELP INC. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 20-1854266 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 140 New Montgomery Street, 9 th Floor San Francisco, California 94105 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (415) 908-3801 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, par value $0.000001 per share New York Stock Exchange LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES x NO ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. YES ¨ NO x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Filed by Grubhub Inc. Pursuant to Rule 425 Under the Securities Act of 1933 and Deemed Filed Pursuant to Rule 14A-12 Under the S

Filed by Grubhub Inc. pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act of 1933 and deemed filed pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Subject Company: Grubhub Inc. Commission File No.: 001-36389 GRUB Employee Email From: Matt Maloney, CEO Subject: A New Chapter for Grubhub Team, I know this note reaches you all at a time of great uncertainty. In addition to a pandemic that has disrupted our lives and impacted our friends and family, our country is struggling with widespread frustration, anger and sadness based on recent events that have reminded us, yet again, that we have a long way to go before our country achieves racial equality. As you know, Grubhub is committed to supporting you and doing our part to help you and our broader community, including our diners, restaurants and drivers through this incredibly challenging time. However, this email is to communicate something different – an important decision made by the board today and with my recommendation. After 20 years of building this industry from the ground up in the U.S., today we begin a new chapter for Grubhub. We have signed a definitive agreement with European industry leader Just Eat Takeaway.com in an all-stock merger to create the largest global online ordering/delivery company in the world (outside of China). Together, we will connect more than 360,000 restaurants to over 70 million active diners in 25 countries. You can read the press release here, and I encourage you to join our town hall meeting at 4:30 p.m. -

Online Food and Beverage Sales Are Poised to Accelerate — Is the Packaging Ecosystem Ready?

Executive Insights Volume XXI, Issue 4 Online Food and Beverage Sales Are Poised to Accelerate — Is the Packaging Ecosystem Ready? The future looks bright for all things ecommerce primary and secondary ecommerce food and beverage packaging. in the food and beverage sector, fueled by What do the key players need to consider as they position themselves to win in this brave new world? Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods, a growing Can the digital shelf compete with the real thing? millennial consumer base and increased Historically, low food and beverage ecommerce penetration consumer adoption rates driven by retailers’ rates have been fueled by both a dearth of affordable, quality push to improve the user experience. But this ecommerce options and consumer inertia. First, brick-and-mortar optimism isn’t confined to grocery retailers, meal grocery retailers typically see low-single-digit profit margins due to the high cost of managing perishable products and cold-chain kit companies and food-delivery outfits. distribution. No exception to that rule, ecommerce retail grocers struggle with the same challenges of balancing overhead with Internet sales are forecast to account for 15%-20% of the food affordable retail prices. and beverage sector’s overall sales by 2025 — a potential tenfold increase over 2016 — which foreshadows big opportunities for Consumers have also driven lagging sales, lacking enthusiasm for food and beverage packaging converters that can anticipate the a model that has seen challenges in providing quick fulfillment evolving needs of brand owners and consumers (see Figure 1). and delivery service — especially for unplanned or impulse And the payoff could be just as lucrative for food and beverage buys. -

Copyright by Isabella Marie Gee 2019 the Dissertation Committee for Isabella Marie Gee Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Isabella Marie Gee 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Isabella Marie Gee certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Deliver Me from Waste: Impacts of E-Commerce on Food Supply Chain Energy Use Committee: Michael E. Webber, Supervisor David T. Allen Joshua Apte Kasey M. Faust Katherine E. Lieberknecht Deliver Me from Waste: Impacts of E-Commerce on Food Supply Chain Energy Use by Isabella Marie Gee DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 I want to thank my friends and family for their unending support during my research. Thank you to my friends for letting me talk about your food and ask about your trash for years. Thank you also to my family; words cannot express how grateful I am for you all. This work is dedicated to you. In particular, I dedicate this to the original Dr. Gee, my Granddad. Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge everyone who made this work possible. I first want to thank my advisor, Dr. Webber, for your constant support and guidance. Thank you to Dr. Webber and Dr. Faust for providing much of the inspiration for this work through your classes on energy and society as well as system-of-systems analysis. Thank you to Todd Davidson, this dissertation would not be possible without your difficult questions and thoughtful critiques. I also want to thank Pete Pearson, Monica McBride, and everyone at World Wildlife Fund; working with you all helped me define the bigger picture and direction for this dissertation. -

UBER COMPLETES ACQUISITION of POSTMATES Combination Of

UBER COMPLETES ACQUISITION OF POSTMATES Combination of platforms provides more choice and convenience for consumers, new demand and tailored technology offerings for restaurants, and increased income opportunities for delivery people SAN FRANCISCO — Uber Technologies, Inc. (NYSE: UBER) today announced that it has completed the acquisition of Postmates Inc. in an all-stock transaction, and that the two companies have begun the process of integrating U.S. operations. As previously announced, the transaction brings together Uber’s global Mobility and Delivery platform with Postmates’ beloved business in the U.S. to strengthen the delivery of food, groceries, essentials, and other goods. The consumer-facing Postmates and Uber Eats apps will continue to run separately, supported by a more efficient, combined merchant and delivery network. In connection with the closing, Uber has signaled its commitment to the success of the restaurants and merchants who use its technology to reach customers and delivery people by announcing a national listening tour. These efforts are designed to better understand merchants’ needs, and to continue to develop products, services, and policies that protect their interests. “Uber and Postmates have long been committed to powering delivery services that support local commerce and communities, all the more important during crises like the one we face today. We’re thrilled to bring these two teams together to continue to innovate, bringing ever-better products and services for merchants, delivery people, and consumers across the country,” said Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi. “We built Postmates to empower local commerce and bring the best of your city to your home, especially in cities like Los Angeles and across the southwest," said Bastian Lehmann, co-founder and CEO of Postmates. -

Just Eat Takeaway.Com Receives All Regulatory Approvals Required in Respect of Its Proposed Acquisition of Grubhub

NOT FOR RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION, IN WHOLE OR IN PART, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, IN, INTO OR FROM ANY JURISDICTION WHERE TO DO SO WOULD CONSTITUTE A VIOLATION OF THE RELEVANT LAWS OF THAT JURISDICTION Amsterdam, 4 September 2020 Just Eat Takeaway.com receives all regulatory approvals required in respect of its proposed acquisition of Grubhub Just Eat Takeaway.com N.V. (AMS: TKWY, LSE: JET), (the “Company” or “Just Eat Takeaway.com”) and Grubhub Inc. (NYSE: GRUB) (“Grubhub”) announce receipt of all regulatory approvals required in respect of Just Eat Takeaway.com’s proposed acquisition of Grubhub. On 10 June 2020, Just Eat Takeaway.com and Grubhub announced that the parties had entered into a definitive agreement (the “Merger Agreement”) whereby Just Eat Takeaway.com is to acquire 100% of the shares of Grubhub in an all-share combination (the “Transaction”). Just Eat Takeaway.com and Grubhub announced that the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (“CFIUS”) has concluded its review of the Transaction under Section 721 of the Defense Production Act of 1950 and has determined that there are no unresolved national security concerns with respect to the Transaction. As previously disclosed on 2 July 2020, the United Kingdom Competition and Markets Authority (the “CMA”) indicated in a response to a briefing paper submitted by Just Eat Takeaway.com in relation to the Transaction that it had no further questions, and on 7 July 2020, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission granted early termination of the waiting period under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, as amended, with respect to the Transaction. -

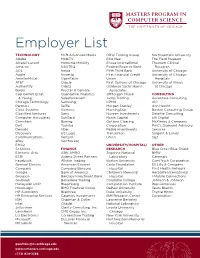

Employer List

Employer List TECHNOLOGY MLB Advanced Media DRW Trading Group Northwestern University Adobe MobiTV Ellie Mae The Field Museum Alcatel-Lucent Motorola Mobility Enova International Theorem Clinical Amazon NAVTEQ Federal Reserve Bank Research AOL Nokia Fifth Third Bank University of Chicago Apple Novetta First Financial Credit University of Chicago ArcellorMittal OpenTable Union Hospitals AT&T Oracle First Options of Chicago University of Illinois Authentify Orbitz Goldman Sachs Harris at Chicago Baidu Procter & Gamble Associates Cap Gemini Ernst Quantative Analytics JPMorgan Chase CONSULTING & Young Salesforce.com Jump Trading Accenture Consulting Chicago Technology Samsung KPMG AIC Partners Selfie Morgan Stanley Aon Hewitt Cisco Systems Siemens MorningStar Boston Consulting Group Classified Ventures Sony Nuveen Investments Deloitte Consulting Computer Associates SunGard Ronin Capital EKI Digital Comshare Boeing Options Clearing McKinsey & Company Dell Toshiba Corporation PwC’s Diamond Advisory Denodo Uber Peak6 Investments Services Discovery US Logic TransUnion Sargent & Lundy Communications Verizon USAA Sg2 eBay VertMarket EMC2 UNIVERSITY/HOSPITAL/ OTHER Solutions FINANCE RESEARCH Blue Cross-Blue Shield Eletronic Arts ABN AMRO Argonne National BMW ESRI Adams Street Partners Laboratory Caremark Facebook Allston Trading Boston University ComPsych Corporation General Electric American Express Carle Foundation Eli Lilly & Company Company Company Bancorp Hospital First Health Network Google Bank of America Children’s Memorial Herbalife International Groupon Barclays Investment Bank Hospital i-Mobile Connections GrubHub Belvedere Trading Columbia College Johnson & Johnson Honeywell UOP Bloomberg Computation Institute PepsiAmericas HookLogic BMO Financial Group DePaul University Sears Brands HP Autonomy Braintree Duke University Toyota Motor HP Enterprise Services Calamos Investments IBM Research Center Corporation IBM Chapman & Cutler Lawrence Berkeley Intel Citadel National Laboratory Jellyvision Clarity Consulting, Inc. -

Opentable Adds Delivery

OpenTable Adds Delivery July 24, 2019 Caviar, Grubhub, Uber Eats partnerships enable delivery and pick-up through OpenTable's app SAN FRANCISCO, July 24, 2019 /PRNewswire/ -- OpenTable, the world's leading provider of online restaurant reservations and part of Booking Holdings, Inc. (NASDAQ: BKNG), today announced that it has partnered with Caviar, Grubhub and Uber Eats to offer delivery and pick-up options at thousands of restaurants on OpenTable's newly updated iOS app. OpenTable helps diners discover and book the best restaurant for any occasion, whether they are looking for a special night out or a restaurant quality meal at home. Diners can now select from multiple delivery providers to order a meal in a few simple taps. By adding delivery and pick-up as an option, OpenTable provides a more comprehensive picture of dining choices in one place. "Sometimes plans change or the weather doesn't cooperate. Instead of canceling their reservation, diners can now enjoy the meal they had planned from home," said Joseph Essas, CTO, OpenTable. "Our goal is to make OpenTable the go-to app for all dining occasions. Adding delivery is an important next step." "While we know that our diners love to join us to get the full restaurant experience, we understand they need options for when they can't make it in," said Dan Simons, Co-owner & Founder, Farmers Restaurant Group. "Delivery through OpenTable gives us the flexibility to attract and serve diners, no matter where they are and how they want their meal." When searching for a restaurant or visiting a restaurant profile page on OpenTable's iOS app, diners will see a "Get it delivered" button or carousel. -

AGC-Restaurant-Tech-Nov-2019

Type & Color November, 2019 INSIGHTS The Future of Restaurant Technology How Technology is Transforming the Restaurant Industry Greg Roth, Partner Ben Howe, CEO Jon Guido, Partner & COO Sean Tucker, PartnerAGC Partners ExecutiveType & Color Summary Massive $900B market experiencing rapid digital adoption and software growth . An extended economic recovery, low unemployment rate, and continued rise of millennials as the largest demographic in the workplace are factors driving strong restaurant spending . Third party delivery market is exploding; eating in is the new dining out US Digital Restaurant Sales . Cloud based POS systems are replacing incumbent providers at an accelerating pace and ($ Billions) achieving higher ACV with additional features and functionality $328 . Front of house applications including Online Ordering, CRM and Loyalty programs are other areas of accelerating spend in order to capture more valuable repeat diners 27% CAGR . Razor thin profit margins and unique challenges restaurants face require purpose built solutions to cut costs, gain efficiencies, and increase visibility . Hiring, training and retaining workers in a complex and changing regulatory environment is one $117 of the largest challenges restaurants face $48 . Unlocking of data silos enabling business analytics across the value chain . Automation and AI beginning to impact restaurant operations and economics, freeing up scarce employee resources to focus on customers 2017 2020 2025 . Ghost Kitchens and Online Catering are two emerging growth areas taking advantage of online Note: based on estimated percentage of sales derived from digital channels and total industry sales forecasts delivery trends and attractive unit economics . Restaurant Management Software spend tilted towards front of house (~60%) technologies vs. -

The Future of Restaurant Marketing

The Future of Restaurant Marketing Marketing is constantly evolving. Especially for restaurants and the food service industry. The reason for this is technological advances. A company’s website is receiving less traffic than they did before; still, some restaurants are seeing significantly MORE organic walk-ins while some are seeing significantly LESS organic walk-ins to their establishment. The key reasons? Apps, maps, review sites, and sophisticated search phrases. Some brick-and-mortar- only establishments receive up to 2.7x as many views and impressions on apps, search engines, and social network sites than they do their own website. For some in food service, that estimation is closer to 10x more impressions on 3rd party listings than they do their own website. The businesses achieving such high results are leveraging technology better than their counterparts. Additionally, “food near me” is no longer one of the top used search phrase for restaurants. Virtual assistants such as Amazon Alexa, Siri, Cortana and other virtual assistants are partially the cause. Users are now searching phrases such as, “Ok Google, who has the best tacos in Austin?” and search engines are utilizing location, listing site reviews, search engine reviews and other data to populate the best answer for that individual. What does this mean? It means if your Mexican food restaurant doesn’t have an online menu, your online listings didn’t have the word “taco” as an attribute, or your review ratings are low, chances are you didn’t break the top 20 results. The nuances in the different devices are just as important to take note of.