Downloaded from on 1/10/2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Updating the Seabird Fauna of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia

Tirtaningtyas & Yordan: Seabirds of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia, update 11 UPDATING THE SEABIRD FAUNA OF JAKARTA BAY, INDONESIA FRANSISCA N. TIRTANINGTYAS¹ & KHALEB YORDAN² ¹ Burung Laut Indonesia, Depok, East Java 16421, Indonesia ([email protected]) ² Jakarta Birder, Jl. Betung 1/161, Pondok Bambu, East Jakarta 13430, Indonesia Received 17 August 2016, accepted 20 October 2016 ABSTRACT TIRTANINGTYAS, F.N. & YORDAN, K. 2017. Updating the seabird fauna of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia. Marine Ornithology 45: 11–16. Jakarta Bay, with an area of about 490 km2, is located at the edge of the Sunda Straits between Java and Sumatra, positioned on the Java coast between the capes of Tanjung Pasir in the west and Tanjung Karawang in the east. Its marine avifauna has been little studied. The ecology of the area is under threat owing to 1) Jakarta’s Governor Regulation No. 121/2012 zoning the northern coastal area of Jakarta for development through the creation of new islands or reclamation; 2) the condition of Jakarta’s rivers, which are becoming more heavily polluted from increasing domestic and industrial waste flowing into the bay; and 3) other factors such as incidental take. Because of these factors, it is useful to update knowledge of the seabird fauna of Jakarta Bay, part of the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. In 2011–2014 we conducted surveys to quantify seabird occurrence in the area. We identified 18 seabird species, 13 of which were new records for Jakarta Bay; more detailed information is presented for Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi. To better protect Jakarta Bay and its wildlife, regular monitoring is strongly recommended, and such monitoring is best conducted in cooperation with the staff of local government, local people, local non-governmental organization personnel and birdwatchers. -

India: Kaziranga National Park Extension

INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 22–27, 2019 The true star of this extension was the Indian One-horned Rhinoceros (Photo M. Valkenburg) LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION February 22–27, 2019 By Machiel Valkenburg This wonderful Kaziranga extension was part of our amazing Maharajas’ Express train trip, starting in Mumbai and finishing in Delhi. We flew from Delhi to Guwahati, located in the far northeast of India. A long drive later through the hectic traffic of this enjoyable country, we arrived at our lodge in the evening. (Photo by tour participant Robert Warren) We enjoyed three full days of the wildlife and avifauna spectacles of the famous Kaziranga National Park. This park is one of the last easily accessible places to find the endangered Indian One-horned Rhinoceros together with a healthy population of Asian Elephant and Asiatic Wild Buffalo. We saw plenty individuals of all species; the rhino especially made an impression on all of us. It is such an impressive piece of evolution, a serious armored “tank”! On two mornings we loved the elephant rides provided by the park; on the back of these attractive animals we came very close to the rhinos. The fertile flood plains of the park consist of alluvial silts, exposed sandbars, and riverine flood-formed lakes called Beels. This open habitat is not only good for mammals but definitely a true gem for some great birds. Interesting but common birds included Bar-headed Goose, Red Junglefowl, Woolly-necked Stork, and Lesser Adjutant, while the endangered Greater Adjutant and Black-necked Stork were good hits in the stork section. -

Landscape, Legal, and Biodiversity Threats That Windows Pose to Birds: a Review of an Important Conservation Issue

Land 2014, 3, 351-361; doi:10.3390/land3010351 OPEN ACCESS land ISSN 2073-445X www.mdpi.com/journal/land/ Review Landscape, Legal, and Biodiversity Threats that Windows Pose to Birds: A Review of an Important Conservation Issue Daniel Klem, Jr. Acopian Center for Ornithology, Department of Biology, Muhlenberg College, 2400 Chew Street, Allentown, PA 18104, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-484-664-3259 Received: 31 December 2013; in revised form: 12 March 2014 / Accepted: 13 March 2014 / Published: 24 March 2014 Abstract: Windows in human residential and commercial structures in urban, suburban, and rural landscapes contribute to the deaths of billions of birds worldwide. International treaties, federal, provincial, state, and municipal laws exist to reduce human-associated avian mortality, but are most often not enforced for bird kills resulting from window strikes. As an additive, compared to a compensatory mortality factor, window collisions pose threats to the sustainability and overall population health of common as well as species of special concern. Several solutions to address the window hazard for birds exist, but the most innovative and promising need encouragement and support to market, manufacture, and implement. Keywords: bird-window collisions; collision prevention; building and landscape architecture; conservation 1. Introduction Clear and reflective windows in human structures of all sizes in urban, suburban, and rural settings are unintentionally killing vast numbers of birds the world over [1–3]. The annual toll of bird deaths from striking windows range from 100 million to 1 billion (latest quantitative estimate based on available data is 365–988 million) in the United States (U.S.), from 16 to 42 million in Canada [4–7]. -

Assam Extension I 17Th to 21St March 2015 (5 Days)

Trip Report Assam Extension I 17th to 21st March 2015 (5 days) Greater Adjutant by Glen Valentine Tour leaders: Glen Valentine & Wayne Jones Trip report compiled by Glen Valentine Trip Report - RBT Assam Extension I 2015 2 Top 5 Birds for the Assam Extension as voted by tour participants: 1. Pied Falconet 4. Ibisbill 2. Greater Adjutant 5. Wedge-tailed Green Pigeon 3. White-winged Duck Honourable mentions: Slender-billed Vulture, Swamp Francolin & Slender-billed Babbler Tour Summary: Our adventure through the north-east Indian subcontinent began in the bustling city of Guwahati, the capital of Assam province in north-east India. We kicked off our birding with a short but extremely productive visit to the sprawling dump at the edge of town. Along the way we stopped for eye-catching, introductory species such as Coppersmith Barbet, Purple Sunbird and Striated Grassbird that showed well in the scopes, before arriving at the dump where large frolicking flocks of the endangered and range-restricted Greater Adjutant greeted us, along with hordes of Black Kites and Eastern Cattle Egrets. Eastern Jungle Crows were also in attendance as were White Indian One-horned Rhinoceros and Citrine Wagtails, Pied and Jungle Mynas and Brown Shrike. A Yellow Bittern that eventually showed very well in a small pond adjacent to the dump was a delightful bonus, while a short stroll deeper into the refuse yielded the last remaining target species in the form of good numbers of Lesser Adjutant. After our intimate experience with the sought- after adjutant storks it was time to continue our journey to the grassy plains, wetlands, forests and woodlands of the fabulous Kaziranga National Park, our destination for the next two nights. -

Painted Storks Mycteria Leucocephala Breeding in Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary, Kerala Shibi Moses

126 Indian BIRDS VOL. 10 NO. 5 (PUBL. 2 NOVEMBER 2015) Painted Storks Mycteria leucocephala breeding in Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary, Kerala Shibi Moses Moses, S., 2015. Painted Storks Mycteria leucocephala breeding in Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary, Kerala. Indian BIRDS 10 (5): 126–127. Shibi Moses, Chackalayil, Kumaranparambil House, Puthuppally PO, Kottayam 686011, Kerala, India. E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received on 26 August 2014. he Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary (9.62ºN, 76.42ºE) is located and bushy shrubs. The trees were inaccessible either by land or on the banks of the Vembanad Lake, in Kerala. It is 14 km by boat. A watchtower, about 120 m away and 8 m high, was Twest of Kottayam town, the headquarters of the eponymous the only vantage point that could be used for these observations. district. It has Vembanad Lake on its west, the Kumarakom– The branches chosen for the nest sites were bare, despite new Vechoor road on its east, the Kavanar River on the north, and leafy offshoots, and this provided some visibility even from this the KTDC Waterscapes Hotel on the south as its borders. It is distance. Since this opportunity was unique, I decide to monitor a regular nesting and roosting site for eleven species of water the nests on an irregular basis without being stationed at the nest birds like the Great Egret Casmerodius albus, Intermediate site throughout the day. Kumarakom being a mixed heronry, the Egret Mesophoyx intermedia, Little Egret Egretta garzetta, Great birds were tolerant to minor disturbances by visitors and did not Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, Indian Cormorant P. -

Sarawak—A Neglected Birding Destination in Malaysia RONALD ORENSTEIN, ANTHONY WONG, NAZERI ABGHANI, DAVID BAKEWELL, JAMES EATON, YEO SIEW TECK & YONG DING LI

30 BirdingASIA 13 (2010): 30–41 LITTLE-KNOWN AREA Sarawak—a neglected birding destination in Malaysia RONALD ORENSTEIN, ANTHONY WONG, NAZERI ABGHANI, DAVID BAKEWELL, JAMES EATON, YEO SIEW TECK & YONG DING LI Introduction It is our hope that this article will be a catalyst One of the ironies of birding in Asia is that despite for change. Alhough much of Sarawak has been the fact that Malaysia is one of the most popular logged and developed, the state still contains destinations for birdwatchers visiting the region, extensive tracts of rainforest habitat; it is still one very few visit the largest state in the country. of the least developed states in Malaysia once away Peninsular Malaysia, and the state of Sabah in east from the four main coastal cities. Given its extensive Malaysia, are well-known and are visited several coastline, Sarawak contains excellent wintering times a year by international bird tour operators grounds for waders and other waterbirds. BirdLife as well as by many independent birdwatchers. But International has designated 22 Important Bird Areas Malaysia’s largest state, Sarawak, which sits (IBAs) in Sarawak, the highest number for any state between the two and occupies one fifth of eastern in Malaysia and more than in all the states of west Borneo, is unfortunately often overlooked by Malaysia combined (18), whilst Sabah has 15 IBAs birdwatchers. The lack of attention given to (Yeap et al. 2007). Sarawak is not only a loss for birders, but also to the state, as the revenue that overseas birdwatchers Why do birders neglect Sarawak? bring in can be a powerful stimulus for protecting That Sarawak is neglected is clear from an examination forests, wetlands and other important bird habitats. -

Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia Peter Pyle and John Engbring for Ornithologists Visiting Micronesia, R.P

./ /- 'Elepaio, VoL 46, No.6, December 1985. 57 Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia Peter Pyle and John Engbring For ornithologists visiting Micronesia, R.P. Owen's Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia (1977a) has proven a valuable reference for species occurrence among the widely scattered island groups. Since its publication, however, our knowledge of species distribution in Micronesia has been substantially augmented. Numerous species not recorded by Owen in Micronesia or within specific Micronesian island groups have since been reported, and the status of many other species has changed or become better known. This checklist is essentially an updated version of Owen (1977a), listing common and scientific names, and occurrence status and references for all species found in Micronesia as recorded from the island groups. Unlike Owen, who gives the status for each species only for Micronesia as a whole, we give it for -each island group. The checklist is stored on a data base program on file with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in Honolulu, and we encourage comments and new or additional information concerning its contents. A total of 224 species are included, of which 85 currently breed in Micronesia, 3 have become extinct, and 12 have been introduced. Our criteria for-species inclusion is either specimen, photograph, or adequately documented sight record by one or more observer. An additional 13 species (listed in brackets) are included as hypothetical (see below under status symbols). These are potentially occurring species for which reports exist that, in our opinion, fail to meet the above mentioned criteria. -

The Waterbirds and Coastal Seabirds of Timor-Leste: New Site Records Clarifying Residence Status, Distribution and Taxonomy

FORKTAIL 27 (2011): 63–72 The waterbirds and coastal seabirds of Timor-Leste: new site records clarifying residence status, distribution and taxonomy COLIN R. TRAINOR The status of waterbirds and coastal seabirds in Timor-Leste is refined based on surveys during 2005–2010. A total of 2,036 records of 82 waterbird and coastal seabirds were collected during 272 visits to 57 Timor-Leste sites, and in addition a small number of significant records from Indonesian West Timor, many by colleagues, are included. More than 200 new species by Timor-Leste site records were collected. Key results were the addition of three waterbirds to the Timor Island list (Red-legged Crake Rallina fasciata, vagrant Masked Lapwing Vanellus miles and recent colonist and Near Threatened Javan Plover Charadrius javanicus) and the first records in Timor-Leste for three irregular visitors: Australian White Ibis Threskiornis molucca, Ruff Philomachus pugnax and Near Threatened Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata. Records of two subspecies of Gull-billed Tern Gelochelidon nilotica, including the first confirmed records outside Australia of G. n. macrotarsa, were also of note. INTRODUCTION number of field projects in Timor-Leste, including an Important Bird Areas programme and a doctoral study (Trainor et al. 2007a, Timor Island lies at the interface of continental South-East Asia and Trainor 2010). The residence status and nomenclature for some Australia and consequently its resident waterbird and coastal seabird species listed in a fieldguide (Trainor et al. 2007b) and recent review avifauna is biogeographically mixed. Some of the most notable (Trainor et al. 2008) are clarified. Three new island records are findings of a Timor-Leste field survey during 2002–2004 were the documented and substantial new ecological data on distribution discovery of resident breeding populations of the essentially Australian and habitat use are included. -

The Species Composition and Distribution Patterns of Non-Native Fishes in the Main Rivers of South China

sustainability Article The Species Composition and Distribution Patterns of Non-Native Fishes in the Main Rivers of South China Dang En Gu 1,2,3, Fan Dong Yu 1,2,3, Yin Chang Hu 2, Jian Wei Wang 1,*, Meng Xu 2, Xi Dong Mu 2, Ye Xin Yang 2, Du Luo 2, Hui Wei 2, Zhi Xin Shen 4, Gao Jun Li 4, Yan Nan Tong 4 and Wen Xuan Cao 1 1 Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430072, China; [email protected] (D.E.G.); [email protected] (F.D.Y.); [email protected] (W.X.C.) 2 Pearl River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Key Laboratory of Recreational Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Guangzhou 510380, China; [email protected] (Y.C.H.); [email protected] (M.X.); [email protected] (X.D.M.); [email protected] (Y.X.Y.); [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (H.W.) 3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 4 Hainan Academy of Ocean and Fisheries Sciences, Haikou 570100, China; [email protected] (Z.X.S.); [email protected] (G.J.L.); [email protected] (Y.N.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-6878-0033 Received: 19 April 2020; Accepted: 29 May 2020; Published: 3 June 2020 Abstract: Non-native fish invasions are among the greatest threats to the sustainability of freshwater ecosystems worldwide. Tilapia and catfish are regularly cultured in South China which is similar to their climate in native areas and may also support their invasive potential. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

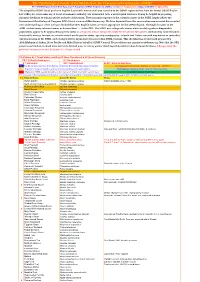

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Karuppiah KANNAN, Jeyaraj A. JOHNSON*, Ajit KUMAR, and Sandeep K

ACTA ICHTHYOLOGICA ET PISCATORIA (2014) 44 (1): 3–8 DOI: 10.3750/AIP2014.44.1.01 MITOCHONDRIAL DNA VARIATION IN THE ENDANGERED FISH DAWKINSIA TAMBRAPARNIEI (ACTINOPTERYGII: CYPRINIFORMES: CYPRINIDAE) FROM SOUTHERN WESTERN GHATS, INDIA Karuppiah KANNAN, Jeyaraj A. JOHNSON*, Ajit KUMAR, and Sandeep K. GUPTA Wildlife Institute of India, 18 Chandrabani, Dehradun, 248001, Uttarkhand, India Kannan K., Johnson J.A., Kumar A., Gupta S.K. 2014. Mitochondrial DNA variation in the endangered fish Dawkinsia tambraparniei (Actinopterygii: Cyprin iformes: Cyprinidae) from southern Western Ghats, India. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 44 (1): 3–8. Background. Dawkinsia tambraparniei (Silas, 1954) is confined to an area not exceeding 100 km2 within a sin- gle watershed—the Tamiraparani River, southern Western Ghats, India. Its populations have recently declined, earning the fish the endangered status. For effective conservation efforts it is important to determine the levels of genetic variation between different populations. Therefore we attempted to quantify the cytochrome b (Cyt b) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene sequence similarity between different populations of D. tambraparniei, as well as to study the phylogenetic relation with the closely related species D. arulius and D. filamentosa. Materials and methods. Samples were collected from 9 locations and 10 individuals from each were preserved for DNA analysis. The partial sequence of Cyt b and COI genes were amplified and sequenced. The sequences were aligned by the visual method using BioEdit version 7.1.3.0 and edited using Sequencer 4.7. The Bayesian consensus tree was constructed using the Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) method by BEAST v1.7.5. -

A Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia

A Checklist of the Birds of Micronesia ROBERT P. OWEN Chief Conservationist, Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands Koror, Palau, Caroline Islands 96940 Abstract.-This paper lists 191 species of birds found in Micronesia based on publications on collections and acceptable sight records. The last published checklist of Micronesian birds was published by Baker (1951) and lists 151 species. This present checklist records the English names, scientific names, and geographic localities within Micronesia in which the different species are found, and also gives status information on the birds such as whether resident, migrant or vagrant, and whether introduced, endangered or extinct. The most comprehensive publication on Micronesian birds is that produced by Baker (1951). That publication was based on field work done by Rollin H. Baker and other U. S. military biologists carried out in Micronesia in 1945 and a review of all publications on Micronesian ornithology prior to that date, and up to 1948. In the intervening 29 years, a good many ornithologists and other biologists have traveled or resided in Micronesia for various periods of time and have published accounts of birds seen or collected in Micronesia. Baker (1951) listed 151 full species of birds in Micronesia. The present checklist (Table 1) contains 191 full species. Thus 40 bird species have been added to the list of birds known from Micronesia from published records. Approximately one fourth of the bird species listed in this checklist are based on published sight records. Great care has been used in evaluating published sight records and several have been rejected for one reason or another for inclusion in this publication.