Leave No Trace (Dir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Game of Thrones,' 'Fleabag' Take Top Emmy Honors on Night of Upsets

14 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2019 Stars hit Emmy red carpet Jodie Maisie Comer Natasha Lyonne Williams Michelle Williams Naomi Watts Sophie Turner Kendall Jenner Vera Farmiga Julia Garner beats GoT stars to win ‘Game of Thrones,’ ‘Fleabag’ take top first Emmy Los Angeles Emmy honors on night of upsets ctress Julia Gar- Los Angeles Emmy for comedy writing. Aner beat “Game of “This is just getting ridiculous!,” Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Thrones” stars, including edieval drama “Game Waller-Bridge said as she accept- ‘Fleabag’ wins big at Emmys Sophie Turner, Lena Head- of Thrones” closed ed the comedy series Emmy. Los Angeles ey, Maisie Williams, to win Mits run with a fourth “It’s really wonderful to know, her first Emmy in Support- Emmy award for best drama se- and reassuring, that a dirty, angry, ctress Phoebe Waller-Bridge won Lead ing Actress in a Drama Se- ries while British comedy “Flea- messed-up woman can make it Actress in a Comedy Series trophy at ries category at the 2019 bag” was the upset winner for to the Emmys,” Waller-Bridge Athe 71st Primetime Emmy Awards gala Emmy awards here. best comedy series on Sunday on added. here for her role in “Fleabag”, The first-time Emmy a night that rewarded newcom- Already the most- awarded which was also named as the nominee was in contention ers over old favorites. series in best comedy series. with Gwendoline Christie Billy Porter, the star of LGBTQ The Emmys are Hollywood’s Emmy “This is just getting ridicu- (“Game of Thrones”), Head- series “Pose,” won the best dra- top honors in television, and the history lous,” Waller-Bridge said as she ey (“Game of Thrones”), matic actor Emmy, while British night belonged to Phoebe Waller- with accepted the honour for best com- Fiona Shaw (“Killing newcomer Jodie Comer took the Bridge, the star and creator of 38 wins, edy series. -

Download Résumé

[email protected] www.kristinbye.com feature films: kristin Obit / EDITOR A documentary feature about life on the New York Times’ obituary desk. bye Directed by Vanessa Gould. (93 minutes / Kino Lorber) 2016 Tribeca International Film Festival (world premiere), Hot Docs Film Festival (int’l premiere) Rams / CONSULTING EDITOR A documentary feature about legendary German industrial designer Dieter Rams. Directed by Gary Hustwit. Stray Dog / ADDITIONAL EDITOR (in conjunction with The Edit Center) A documentary portrait of Ron “Stray Dog” Hall: Vietnam vet, biker and lover of small dogs. Directed by Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone). 2014 LA Film Festival, Jury Award Best Documentary Ivory Tower / ASSISTANT EDITOR A documentary feature that explores the cost and value of higher education in the United States. Directed by Andrew Rossi (Page One: Inside the New York Times) for CNN Films. 2014 Sundance Film Festival Ride, Rise, Roar / ASSISTANT EDITOR A David Byrne concert documentary feature. Directed by Hillman Curtis. 2010 SXSW and SilverDocs Film Festivals Inside Job / PRODUCTION ASSISTANT A documentary about the 2008 financial crisis. Directed by Charles Ferguson. 2010 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature; Cannes, New York, Toronto International and Telluride Film Festivals short film clients (commercial & documentary): EDITOR: Bobbi Brown Cosmetics Razorfish Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Revlon Daniel Libeskind R/GA Hillman Curtis Squarespace Knoll Steinway & Sons New York Times TED Nokia United Nations Prescriptives Cosmetics Whitney Museum of American Art Purpose World Health Organization short films (fiction): Drowned Lands Powerhouse Books graphic design: studio 209, inc. PORTLAND, OR / 1997– 2008 Co-founder and partner of graphic design studio in Portland, Oregon, specializing in print and interactive media for a diverse range of clients including Nike, Oregon Symphony, Portland Center Stage, Portland Trailblazers and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. -

Discover Vouchers Accepted at the Ticket Desk & Candy

Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday 3 Jun 4 Jun 5 Jun 6 Jun 7 Jun 8 Jun 9 Jun 127 mins 12:00pm 10:30am 11:30am 10:15am 12:00pm 12:15pm 2:30pm 1:30pm 1:30pm 12:00pm 2:30pm 3:15pm 5:00pm 5:00pm 4:30pm 3:15pm 5:00pm 6:00pm 8:00pm 8:00pm 8:00pm 6:00pm 8:00pm 103 mins 10:15am 10:00am 2:45pm 1:30pm 113 mins 1:00pm 1:00pm 1:00pm 10:00am 1:00pm 1:00pm 3:30pm 3:30pm 1:00pm 3:30pm 3:30pm 6:00pm 6:00pm 6:00pm 3:30pm 6:00pm 6:30pm 8:30pm 8:30pm 8:30pm 6:30pm 8:30pm 149 mins 12:30pm 10:30am 10:30am 10:30am 12:30pm 12:30pm 2:00pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 12:30pm 2:00pm 3:30pm 4:30pm 4:30pm 2:30pm 3:00pm 4:30pm 5:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 7:30pm 6:00pm 7:30pm DISCOVER VOUCHERS 116 mins 10:15am 10:00am ALL ACCEPTED AT THE TICKET DESK TICKETS $12.50 3:15pm 3:15pm 3:15pm 3:15pm 12:00pm & CANDY BAR 6:15pm 6:15pm 6:15pm 6:30pm 6:15pm 3:00pm 134 mins ALL TICKETS 3:45pm 10:15am 10:15am 3:45pm $12.50 114 mins 12:45pm 2 x regular Movie Tickets $25 11:45am 3:45pm 3:45pm 11:45am 12:30pm 5:30pm 1 x regular Movie Ticket plus 115 mins Large or Med Combo = $25 ALL TICKETS 12:15pm 10:00am 5:30pm 1:15pm 12:15pm 6:30pm $12.50 (Not available on Special Events; 3D movies $3 extra) 108 mins 3:45pm 5:15pm 5:45pm 5:45pm 6:30pm 5:15pm 6:15pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 8:45pm 115 mins 10:00am 10:00am 12:45pm Sign up at the Candy 5:45pm 2:30pm 5:00pm 4:00pm 5:45pm 3:45pm Bar. -

Cineson Productions and Film Bridge International

CineSon Productions and Film Bridge International FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ANDY GARCIA,VERA FARMIGA TO STAR IN ROMANTIC COMEDY “ADMISSIONS” Los Angeles, CA,—Andy Garcia and Vera Farmiga are set to star in indie romantic comedy “Admissions,” which Garcia will also produce through his CineSon Productions. Adam Rodgers will direct from a script co-written with Glenn German, who will also produce alongside Sig Libowitz, under his Look at the Moon Productions banner. Ellen Wander of Film Bridge International will executive produce along with Sonya Lunsford (Academy Award-winning box office hit “The Help”), with Wander and FBI handling international distribution. “Admissions” centers on a once-in-a-lifetime relationship that develops between two strangers over the course of a single day. Farmiga portrays Edith, a free-spirited mom taking her driven daughter Audrey on a walking tour of a beautiful small college. Garcia plays buttoned-up heart surgeon George, who’s taking his son Conrad on the same tour. Failing comically to connect with their respective children, George and Edith decide to play “tour hooky” together for the rest of the afternoon. The result is a surprising romance and the greatest half-day of their lives. Academy Award nominee Farmiga (“Up In The Air,” “The Departed,” “Higher Ground,” “Safe House”) has recently wrapped New Line Cinema’s “The Warren Files.” Academy Award nominee Garcia (“The Godfather: Part III”, “The Untouchables”, “Ocean’s 11”) toplines two soon-to-be released films—“For Greater Glory” and “The Truth.” Rodgers’ most recent film as director, “The Response,” was short-listed for the 2010 Academy Awards as Best Live Action Short Film. -

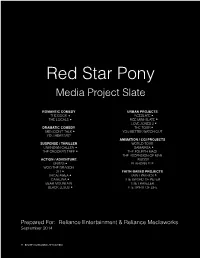

Project Slate

Red Star Pony Media Project Slate ROMANTIC COMEDY! URBAN PROJECTS! THE BOOK RCESLATE THE LOCALS RCE MINI-SLATE ! LOVE JONES 2 DRAMATIC COMEDY! THE TOUR MEN DON’T TALK YOU BETTER WATCH OUT YOU HEAR ME? ! ! ANIMATION / CGI PROJECTS! SUSPENSE / THRILLER! WORLD TOUR UNKNOWN CALLER SAMAIREA THE CROOKED TREE THE FOURTH MAGI ! THE ASCENSION OF MAN ACTION / ADVENTURE! BUDDY UNITAS ELKHORN ELF WOO THE DRAGON ! 311 FAITH-BASED PROJECTS! SACAJAWEA SAINT PATRICK CATALINA THE SWORD OF PETER BEAR MOUNTAIN THE TRAVELER BLACK JESUS THE SPIRIT OF LIFE ! ! ! Prepared For: Reliance Entertainment & Reliance Mediaworks September 2014 BRIEF OVERVIEW ATTACHED THE LOCALS MAJOR MOTION PICTURE Media Type: Major Motion Picture Genre: Romantic Comedy MPAA Rating: PG-13 (anticipated) Logline: The Locals is a comedic love story set in the Bronx about two three-generational families who are set in their ways: the Goldberg’s and the Romano’s. Their perspectives on life are challenged as love, and illness, strikes both families. The Locals is a modern day Moonstruck meets Little Miss Sunshine. Production Budget: $6.4M The Locals Location: New York (25% tax incentive, estimated) Financing: $3M equity; 100% gross receipts until 115% recoupment; 50% gross receipts thereafter Producers: Sue Kramer, Jill Footlick, James Sinclair Writer: Sue Kramer Director: Sue Kramer (Gray Matters, The God of Driving) Distribution: TBD (domestic); IM Global * (international) Cast: TBD * ! ! ! ! ! Shirley MacLaine Alan Arkin Vera Farmiga Richard Schiff Annabella Sciorra Alfred Molina Odeya -

CV Jan Thijs 20151112

JAN THIJS Unit Still Photographer www.janthijs.com STORY OF YOUR Amy Adams FILMNATION ENTERTAINMENT LIFE Jeremy Renner PARAMOUNT PICTURES Forest Whitaker Dir.: Denis Villeneuve SHUT IN Naomi Watts EUROPACORP/RELATIVITY Oliver Platt MEDIA Charlie Heaton Dir.: Farren Blackburn TUT Sir Ben Kingsley SPIKE TV/ MUSE ENT. Avan Jogia Dir.: David Von Ancken Kylie Bunbury ASCENSION Tricia Helfer SCI-FI Gil Bellows Brian Van Holt REGRESSION Ethan Hawke MOD COMPANY - FIRST Emma Watson GENERATION FILMS Dir.: Alejandro Amenabar RED 2 Bruce Willis SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT Catherine Zeta-Jones LIONSGATE Mary-Louise Parker Dir.: Dean Parisot Helen Mirren John Malkovich THE YOUNG AND Kyle Catlett EPITHÉTE/TAPIOCA PRODIGIOUS Helena Bonham Carter Dir.: Jean-Pierre Jeunet SPIVIT Judy Davis WARM BODIES Nicholas Hoult SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT (Additional stills) Teresa Palmer Dir.: Jonathan Levine John Malkovich RIDDICK Vin Diesel UNIVERSAL STUDIOS Jordi Mollå Dir.: David Twohy Keri Hilson MIRROR MIRROR Julia Roberts RELATIVITY MEDIA Nathan Lane Dir.: Tarsem Singh Lilly Collins Armie Hammer IMMORTALS Henry Cavill RELATIVITY MEDIA Mickey Rourke UNIVERSAL STUDIOS Freida Pinto Dir.: Tarsem Singh Stephan Dorff John Hurt FATAL BAZOOKA Michael Youn LEGENDE FILMS (Fr) Isabelle Funaro Dir.: Michael Youn Stephane Rousseau 1 OSCAR ET Michèle Laroque PAN-EUROPEENNE (Fr) LA DAME ROSE Dir.: Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt ORPHAN Isabelle Fuhrman WARNER BROS. (Additional stills) Vera Farmiga DARK CASTLE ENT. Dir.: Jaume Collet-Serra THE COMPANY Michael Keaton SONY/TNT Alfred Molina Director: -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015

BFI Film Quiz – August 2015 General Knowledge 1 The biographical drama Straight Outta Compton, released this Friday, is an account of the rise and fall of which Los Angeles hip hop act? 2 Only two films have ever won both the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Picture. Name them. 3 Which director links the films Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News & As Good as it Gets, as well as TV show The Simpsons? 4 Which Woody Allen film won the 1978 BAFTA Award for Best Film, beating fellow nominees Rocky, Net- work and A Bridge Too Far? 5 The legendary Robert Altman was awarded a BFI Fellowship in 1991; but which British director of films including Reach for the Sky, Educating Rita and The Spy Who Loved Me was also honoured that year? Italian Film 1 Name the Italian director of films including 1948’s The Bicycle Thieves and 1961’s Two Women. 2 Anna Magnani became the first Italian woman to win the Best Actress Academy Award for her perfor- mance as Serafina in which 1955 Tennessee Williams adaptation? 3 Name the genre of Italian horror, popular during the 1960s and ‘70s, which includes films such as Suspiria, Black Sunday and Castle of Blood. 4 Name Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 debut feature film, which was based on his previous work as a novelist. 5 Who directed and starred in the 1997 Italian film Life is Beautiful, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, amongst other honours. -

How-Movies-Help-Make-The-World

y friend the architect Colin Fraser Wishart says that the purpose of his craft is to help people live better. There’s beautiful simplicity, but also Menormous gravity in that statement. Just imagine if every public building, city park, urban transportation hub, and home were constructed with the flourishing of humanity - in community or solitude - in mind. Sometimes this is already the case, and we know it when we see it. Our minds and hearts feel more free, we breathe more easily, we are inspired to create things - whether they be new thoughts of something hopeful, or friendships with strangers, or projects that will bring the energy of transformation yet still into the lives of others. If architecture, manifested at its highest purpose, helps We comprehend...that nuclear power is us live better, then it is also easy to spot architecture that is divorced from this purpose. a real danger for mankind, that over- In our internal impressions of a building or other space made to function purely within crowding of the planet is the greatest the boundaries of current economic mythology - especially buildings made to house the so-called “making” of money - the color of hope only rarely reveals itself. Instead we danger of all. We have understood that are touched by melancholy, weighed down by drudgery, even compelled by the urge to the destruction of the environment is get away. But when we see the shaping of a space whose stewards seem to have known another enormous danger. But I truly that human kindness is more important than winning, that poetry and breathing matter believe that the lack of adequate beyond bank balances and competition (a concert hall designed for the purest reflection imagery is a danger of the same of sound, a playground where the toys blend in with the trees, a train station where the magnitude. -

Films with 2 Or More Persons Nominated in the Same Acting Category

FILMS WITH 2 OR MORE PERSONS NOMINATED IN THE SAME ACTING CATEGORY * Denotes winner [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 3 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1935 (8th) ACTOR -- Clark Gable, Charles Laughton, Franchot Tone; Mutiny on the Bounty 1954 (27th) SUP. ACTOR -- Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger; On the Waterfront 1963 (36th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Diane Cilento, Dame Edith Evans, Joyce Redman; Tom Jones 1972 (45th) SUP. ACTOR -- James Caan, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino; The Godfather 1974 (47th) SUP. ACTOR -- *Robert De Niro, Michael V. Gazzo, Lee Strasberg; The Godfather Part II 2 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1939 (12th) SUP. ACTOR -- Harry Carey, Claude Rains; Mr. Smith Goes to Washington SUP. ACTRESS -- Olivia de Havilland, *Hattie McDaniel; Gone with the Wind 1941 (14th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Patricia Collinge, Teresa Wright; The Little Foxes 1942 (15th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Dame May Whitty, *Teresa Wright; Mrs. Miniver 1943 (16th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Gladys Cooper, Anne Revere; The Song of Bernadette 1944 (17th) ACTOR -- *Bing Crosby, Barry Fitzgerald; Going My Way 1945 (18th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Eve Arden, Ann Blyth; Mildred Pierce 1947 (20th) SUP. ACTRESS -- *Celeste Holm, Anne Revere; Gentleman's Agreement 1948 (21st) SUP. ACTRESS -- Barbara Bel Geddes, Ellen Corby; I Remember Mama 1949 (22nd) SUP. ACTRESS -- Ethel Barrymore, Ethel Waters; Pinky SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Elsa Lanchester; Come to the Stable 1950 (23rd) ACTRESS -- Anne Baxter, Bette Davis; All about Eve SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter; All about Eve 1951 (24th) SUP. ACTOR -- Leo Genn, Peter Ustinov; Quo Vadis 1953 (26th) ACTOR -- Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster; From Here to Eternity SUP. -

Sundance Institute Announces New 'Filmtwo' Initiative to Support

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: May 17, 2016 Chalena Cadenas 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Announces New ‘FilmTwo’ Initiative to Support SecondTime Feature Filmmakers Created with Support from Founding Partner NBCUniversal Expansion of Signature Programs Addresses Unique Challenges and Barriers to Sustainable Filmmaking Careers 13 Filmmakers Selected for Inaugural FilmTwo Fellowship Andrew Ahn | Shaz Bennett | Bernardo Britto | Steven Caple Jr. | Jonas Carpignano | Marta Cunningham | Alistair Banks Griffin Siân Heder | Marielle Heller | Anna Rose Holmer | Crystal Moselle | Felix Thompson | Yared Zeleke Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute today announced a significant expansion of its signature artist development programs to include targeted support for secondtime feature filmmakers, addressing a growing need in the field of independent storytelling, especially for women and filmmakers of color. The new FilmTwo Initiative, led by the Institute’s renowned Feature Film Program, with generous support from Founding Partner NBCUniversal, will offer selected directors specialized creative and tactical guidance in navigating the unique challenges of making their second feature films. The Initiative’s inaugural Fellows announced today participated in a Screenwriters Intensive in March and continue to receive customized creative and tactical support and participate in select FFP activities. The FilmTwo Initiative was created to provide support to a diverse group of independent filmmakers in response to the specific challenges they face in developing and completing their second feature film, often the greatest barrier to a sustainable career as a filmmaker. These include identifying and/or writing their second project, defining their distinctive voice, scaling up and creating more ambitious projects in terms of budget and scope and a dearth of development financing. -

The Loft Cinema Film Guide

loftcinema.org THE LOFT CINEMA Showtimes: FILM GUIDE 520-795-7777 JANUARY 2020 WWW.LOFTCINEMA.ORG See what films are playing next, buy tickets, look up showtimes & much more! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tamales from Tucson Tamale Company, Burritos from Tumerico, and Ethiopian Wraps JANUARY 2020 from Cafe Desta, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan cookies and more! LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 5 *Pizza served after 5pm daily. NEW FILMS 6-15 35MM SCREENINGS 6 REEL READS SELECTION 12 BEER OF THE MONTH: 70MM SCREENINGS 26, 28 40 HOPPY ANNIVERSARY ALE OSCAR SHORTS 20 SIERRA NEVADA BREWING CO. RED CARPET EVENING 21 ONLY $3.50 WHILE SUPPLIES LAST! SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 22-30 LOFT JR. 24 CLOSED CAPTIONS & AUDIO DESCRIPTIONS! ESSENTIAL CINEMA 25 The Loft Cinema offers Closed Captions and Audio LOFT STAFF SELECTS 29 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our COMMUNITY RENTALS 31-33 website to see which films offer this technology. MONDO MONDAYS 38 CULT CLASSICS 39 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: FREE MEMBERS SCREENING • 1702 Craft Beer & • Epic Cafe • R-Galaxy Pizza 63 UP • Ermanos • Raging Sage (SEE PAGE 8) • aLoft Hotel • Fantasy Comics • Rocco’s Little FRIDAY, JANUARY 10, AT 7:00PM • Antigone Books • First American Title Chicago • Aqua Vita • Frominos • SW University of • Black Crown Visual Arts REGULAR ADMISSION PRICES • Heroes & Villains Coffee • Shot in the Dark $9.75 - Adult | $7.25 - Matinee* • Hotel Congress $8.00 - Student, Teacher, Military • Black Rose Tattoo Cafe • Humanities $6.75 - Senior (65+) or Child (12 & under) • Southern AZ AIDS $6.00 - Loft Members • Bookman’s Seminars Foundation *MATINEE: ANY SCREENING BEFORE 4:00PM • Bookstop • Jewish Community • The Historic Y Tickets are available to purchase online at: • Borderlands Center • Time Market loftcinema.org/showtimes Brewery • KXCI or by calling: 520-795-0844 • Tucson Hop Shop • Brooklyn Pizza • La Indita • UA Media Arts Phone & Web orders are subject to a • Cafe Luce • Maynard’s Market $1 surcharge.