How-Movies-Help-Make-The-World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

Bergt 1 Siena Sofia Bergt Professor Insdorf Analysis of Film Language 26 February 2018 Colored Perspectives: Shading World War II Onscreen Films that deal with World War II—whether their narratives are concerned primarily with the war itself, the aura from which it emerged, or the ethos of its aftermath—have a particularly charged relationship to the presence or abjuration of color. As representations of a period that produced its own black-and-white archival footage, these worKs recKon with color not simply as an aesthetic choice, but also as a tool through which to define their own relationship to perspectival subjectivity and claims of historical authenticity. By examining the role of color in three vastly different World War II films— Andrzej Wajda’s black-and-white 1958 rendition of the war’s last 24 hours in “Ashes and Diamonds,” the Harlequin prewar chaos of Bob Fosse’s 1972 “Cabaret,” and the delicate balance of color and blacK-and-white characterizing the postwar divided Germany of Wim Wenders’ 1987 “Wings of Desire”—we may access a richer understanding, not simply of the films’ stylistic approaches, but also (and perhaps more significantly) of their relationship to both their origins and audience. Color, that is, acts in these three films as a chromatic guide by which to untangle each respective text’s taKe on both subjectivity and objectivity. Bergt 2 The best “entry point” into these stylistically and temporally distinct films’ chromatic motifs is through three strikingly analogous crowd scenes—each of which uses communal participation in a diegetically well-known song to highlight a moment of dramatic urgency or volatility. -

P.O.V. a Danish Journal of Film Studies

Institut for Informations og Medievidenskab Aarhus Universitet p.o.v. A Danish Journal of Film Studies Editor: Richard Raskin Number 8 December 1999 Department of Information and Media Studies University of Aarhus 2 p.o.v. number 8 December 1999 Udgiver: Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab, Aarhus Universitet Niels Juelsgade 84 DK-8200 Aarhus N Oplag: 750 eksemplarer Trykkested: Trykkeriet i Hovedbygningen (Annette Hoffbeck) Aarhus Universitet ISSN-nr.: 1396-1160 Omslag & lay-out Richard Raskin Articles and interviews © the authors. Frame-grabs from Wings of Desire were made with the kind permission of Wim Wenders. The publication of p.o.v. is made possible by a grant from the Aarhus University Research Foundation. All correspondence should be addressed to: Richard Raskin Institut for Informations- og Medievidenskab Niels Juelsgade 84 8200 Aarhus N e-mail: [email protected] fax: (45) 89 42 1952 telefon: (45) 89 42 1973 This, as well as all previous issues of p.o.v. can be found on the Internet at: http://www.imv.aau.dk/publikationer/pov/POV.html This journal is included in the Film Literature Index. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The principal purpose of p.o.v. is to provide a framework for collaborative publication for those of us who study and teach film at the Department of Information and Media Science at Aarhus University. We will also invite contributions from colleagues at other departments and at other universities. Our emphasis is on collaborative projects, enabling us to combine our efforts, each bringing his or her own point of view to bear on a given film or genre or theoretical problem. -

A Theory of Cinematic Selfhood & Practices of Neoliberal Portraiture

Cinema of the Self: A Theory of Cinematic Selfhood & Practices of Neoliberal Portraiture Milosz Paul Rosinski Trinity Hall, University of Cambridge June 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. The dissertation is formatted in accordance to the Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA) style. This dissertation does not exceed the word limit of 80,000 words (as specified by the Modern and Medieval Languages Degree Committee). Summary This thesis examines the philosophical notion of selfhood in visual representation. I introduce the self as a modern and postmodern concept and argue that there is a loss of selfhood in contemporary culture. Via Jacques Derrida, Jean-Luc Nancy, Gerhard Richter and the method of deconstruction of language, I theorise selfhood through the figurative and literal analysis of duration, the frame, and the mirror. -

SPRING 2012 FSCP 81000--Aesthetics of Film

SPRING 2012 FSCP 81000--Aesthetics of Film, Professor Edward Miller, Monday, 4:14-8:15p.m., Room C-419, 3 credits [17259] Cross listed with THEA 71400, ART 79400 & MALS 77100 Ever since the Lumiere Brother's train arrived at the station, film has been concerned with its own mechanics and meanings and the ways in which film not only captures the moment but transforms it, creating an impact upon its audience with distinct aesthetics. This course highlights the self-referentiality of film and argues that a central aspect of the cinematic enterprise is the depiction of the filmmaking environment itself through the "meta- film." Using this emphasis as an entry into aesthetics, the course involves students in graduate- level film discourse by providing them with a thorough understanding of the concepts that are needed to perform a detailed formal analysis. The course's main text is the ninth edition of Bordwell and Thompson's Film Art (2009) and the book is used to examine such key topics as narrative and nonnarrative forms, mise-en-scene, composition, cinematography, camera movement, set design/location, color, duration, editing, sound/music, and genre. In addition, we read key sections of Robert Stam's Reflexivity in Film and Literature: From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard (1992), Christopher Ames' Movies about Movies: Hollywood Revisited (1997), Nöth & Bishara's Self-Reference in the Media (2007), John Thornton Caldwell's Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film & Television (2008), and Lisa Konrath's Metafilms: Forms and Functions of Self-Reflexivity in Postmodern Film (2010) in order to strengthen our understanding of the connections between aesthetics and reflexivity. -

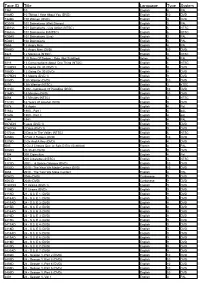

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title 10

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title Film Date Rating(%) 2046 1-Feb-2006 68 120BPM (Beats Per Minute) 24-Oct-2018 75 3 Coeurs 14-Jun-2017 64 35 Shots of Rum 13-Jan-2010 65 45 Years 20-Apr-2016 83 5 x 2 3-May-2006 65 A Bout de Souffle 23-May-2001 60 A Clockwork Orange 8-Nov-2000 81 A Fantastic Woman 3-Oct-2018 84 A Farewell to Arms 19-Nov-2014 70 A Highjacking 22-Jan-2014 92 A Late Quartet 15-Jan-2014 86 A Man Called Ove 8-Nov-2017 90 A Matter of Life and Death 7-Mar-2001 80 A One and A Two 23-Oct-2001 79 A Prairie Home Companion 19-Dec-2007 79 A Private War 15-May-2019 94 A Room and a Half 30-Mar-2011 75 A Royal Affair 3-Oct-2012 92 A Separation 21-Mar-2012 85 A Simple Life 8-May-2013 86 A Single Man 6-Oct-2010 79 A United Kingdom 22-Nov-2017 90 A Very Long Engagement 8-Jun-2005 80 A War 15-Feb-2017 91 A White Ribbon 21-Apr-2010 75 Abouna 3-Dec-2003 75 About Elly 26-Mar-2014 78 Accident 22-May-2002 72 After Love 14-Feb-2018 76 After the Storm 25-Oct-2017 77 After the Wedding 31-Oct-2007 86 Alice et Martin 10-May-2000 All About My Mother 11-Oct-2000 84 All the Wild Horses 22-May-2019 88 Almanya: Welcome To Germany 19-Oct-2016 88 Amal 14-Apr-2010 91 American Beauty 18-Oct-2000 83 American Honey 17-May-2017 67 American Splendor 9-Mar-2005 78 Amores Perros 7-Nov-2001 85 Amour 1-May-2013 85 Amy 8-Feb-2017 90 An Autumn Afternoon 2-Mar-2016 66 An Education 5-May-2010 86 Anna Karenina 17-Apr-2013 82 Another Year 2-Mar-2011 86 Apocalypse Now Redux 30-Jan-2002 77 Apollo 11 20-Nov-2019 95 Apostasy 6-Mar-2019 82 Aquarius 31-Jan-2018 73 -

URMC V123no109 20150220.Pdf (6.062Mb)

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN theweekender Friday, February 20, 2015 FIRST ANNUAL OSCARS EDITION CSU alumnus nominated for an Oscar for his work on short animated film ‘The Dam Keeper’ McKenna Ferguson | page 10 To sum up: quick summaries of the eight Best Picture nominations Arts & Entertainment Desk | page 8 & 9 ‘Boyhood’: Overrated or a new classic? Aubrey Shanahan | page 4 Morgan Smith | page 4 “Why are they even called the ‘Oscars’?” A brief historical timeline of Hollywood’s biggest night Aubrey Shanahan | page 3 abbie parr and kate knapp COLLEGIAN 2 Friday, February 20, 2015 | The Rocky Mountain Collegian collegian.com THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Follow @CollegianC COLLEGIAN on Twitter for the COLLEGIAN PHOTOSHOP OF THE WEEK latest news, photos Lory Student Center Box 13 and video. Fort Collins, CO 80523 This publication is not an offi cial publication of Colorado State University, but is published by Follow our an independent corporation using the name ‘The collegiancentral Rocky Mountain Collegian’ pursuant to a license Instagram for the granted by CSU. The Rocky Mountain Collegian is a 8,000-circulation student-run newspaper intended latest photos. as a public forum. It publishes fi ve days a week during the regular fall and spring semesters. During the last eight weeks of summer Collegian distribution drops to 3,500 and is published Like Collegian weekly. During the fi rst four weeks of summer the Central on Facebook Collegian does not publish. for the latest news, Corrections may be submitted to the editor photos and video. in chief and will be printed as necessary on page two. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Download Résumé

[email protected] www.kristinbye.com feature films: kristin Obit / EDITOR A documentary feature about life on the New York Times’ obituary desk. bye Directed by Vanessa Gould. (93 minutes / Kino Lorber) 2016 Tribeca International Film Festival (world premiere), Hot Docs Film Festival (int’l premiere) Rams / CONSULTING EDITOR A documentary feature about legendary German industrial designer Dieter Rams. Directed by Gary Hustwit. Stray Dog / ADDITIONAL EDITOR (in conjunction with The Edit Center) A documentary portrait of Ron “Stray Dog” Hall: Vietnam vet, biker and lover of small dogs. Directed by Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone). 2014 LA Film Festival, Jury Award Best Documentary Ivory Tower / ASSISTANT EDITOR A documentary feature that explores the cost and value of higher education in the United States. Directed by Andrew Rossi (Page One: Inside the New York Times) for CNN Films. 2014 Sundance Film Festival Ride, Rise, Roar / ASSISTANT EDITOR A David Byrne concert documentary feature. Directed by Hillman Curtis. 2010 SXSW and SilverDocs Film Festivals Inside Job / PRODUCTION ASSISTANT A documentary about the 2008 financial crisis. Directed by Charles Ferguson. 2010 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature; Cannes, New York, Toronto International and Telluride Film Festivals short film clients (commercial & documentary): EDITOR: Bobbi Brown Cosmetics Razorfish Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Revlon Daniel Libeskind R/GA Hillman Curtis Squarespace Knoll Steinway & Sons New York Times TED Nokia United Nations Prescriptives Cosmetics Whitney Museum of American Art Purpose World Health Organization short films (fiction): Drowned Lands Powerhouse Books graphic design: studio 209, inc. PORTLAND, OR / 1997– 2008 Co-founder and partner of graphic design studio in Portland, Oregon, specializing in print and interactive media for a diverse range of clients including Nike, Oregon Symphony, Portland Center Stage, Portland Trailblazers and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. -

W Talking Pictures

Wednesday 3 June at 20.30 (Part I) Wednesday 17 June at 20.30 Thursday 4 June at 20.30 (Part II) Francis Ford Coppola Ingmar Bergman Apocalypse Now (US) 1979 Fanny And Alexander (Sweden) 1982 “One of the great films of all time. It shames modern Hollywood’s “This exuberant, richly textured film, timidity. To watch it is to feel yourself lifted up to the heights where packed with life and incident, is the cinema can take you, but so rarely does.” (Roger Ebert, Chicago punctuated by a series of ritual family Sun-Times) “To look at APOCALYPSE NOW is to realize that most of us are gatherings for parties, funerals, weddings, fast forgetting what a movie looks like - a real movie, the last movie, and christenings. Ghosts are as corporeal an American masterpiece.” (Manohla Darghis, LA Weekly) “Remains a as living people. Seasons come and go; majestic explosion of pure cinema. It’s a hallucinatory poem of fear, tumultuous, traumatic events occur - projecting, in its scale and spirit, a messianic vision of human warfare Talking yet, as in a dream of childhood (the film’s stretched to the flashpoint of technological and moral breakdown.” perspective is that of Alexander), time is (Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly) “In spite of its limited oddly still.” (Philip French, The Observer) perspective on Vietnam, its churning, term-paperish exploration of “Emerges as a sumptuously produced Conrad and the near incoherence of its ending, it is a great movie. It Pictures period piece that is also a rich tapestry of grows richer and stranger with each viewing, and the restoration [in childhood memoirs and moods, fear and Redux] of scenes left in the cutting room two decades ago has only April - July 2009 fancy, employing all the manners and added to its sublimity.” (Dana Stevens, The New York Times) Audience means of the best of cinematic theatrical can choose the original version or the longer 2001 Redux version. -

Berlin 2019: the Once and Future Metropolis

BERLIN 2019: THE ONCE AND FUTURE METROPOLIS URBANIZATION, CONFLICT & COMMUNITY What makes a city? Who decides how a city grows and changes, and what criteria do they use – should it be beautiful, efficient, sustainable, open, just? How do economic systems and political ideologies shape urban development? What is the “right to the city,” and what does it mean for city-dwellers to exercise it? These are just some of the questions we will seek to answer in this summer program in Berlin. Political graffiti in Kreuzberg, 2018. HISTORY, CHANGE & AGENCY QUICK FACTS This program will expose students to the dynamics of LOCATION: Berlin, Germany urban change in one of the most historically freighted and ACADEMIC TERM: Summer A Term 2019 contested cities in the world. They will come to understand ESTIMATED PROGRAM FEE: $4,500 the complex histories behind Berlin’s urban spaces, and the strategies adopted by local actors to deal with those CREDITS: 10 UW credits histories while finding agency to shape them for the future. PREREQUISITES: At least one of the following: CEP 200; URBDP 200 Students will experience first-hand how spaces have been or 300; BE 200; GEOG 276, 277, 301, 303 or 478; SOC 215 or 365; or defined by drivers like economic exigency, political ideology, permission of the instructor. violence, environmental conditions, and technological PROGRAM DIRECTOR: Evan H. Carver ([email protected]) development, and they will learn how contemporary challenges, including climate change, gentrification, and PROGRAM MANAGER: Megan Herzog ([email protected]) immigration butt up against competing ambitions for Berlin PRIORITY APPLICATION DEADLINE: January 31, 2019 to become a “global city” and for it to maintain its distinct INFORMATION SESSIONS: TBD. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film and the Return to Right Now

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2019 Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now Aaron Pellerin Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pellerin, Aaron, "Everyday Transcendence: Contemporary Art Film And The Return To Right Now" (2019). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2333. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2333 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. EVERYDAY TRANSCENDENCE: CONTEMPORARY ART FILM AND THE RETURN TO RIGHT NOW by AARON PELLERIN DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 MAJOR: ENGLISH (Film and Media Studies) Approved By: _________________________________________ Advisor Date _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY AARON PELLERIN 2019 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For Sue, who always sees the magic in the everyday. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I‘d like to thank my committee, and in particular my advisor, Dr. Steve Shaviro. His encouragement, his insightful critiques, and his early advice to just write were all instrumental in making this work what it is. I likewise wish to thank Dr. Scott Richmond for the time and energy he put in as I struggled through the middle stages of the degree. I am also grateful for a series of challenging and exciting seminars I took with Steve, Scott, and also with Dr.