Oliver O'donovan, "Scripture and Christian Ethics,"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

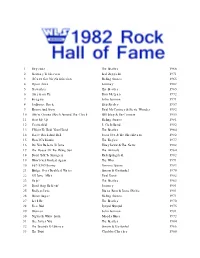

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

032019.Log ********** 88.5 Fm Keom 03/20/19

032019.LOG ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 12:00 A 74 Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder 12:04 A 75 The Way I Want To Touch You Captain & Tennille 12:06 A 70 We've Only Just Begun Carpenters 12:09 A 82 Rock The Casbah Clash 12:16 A 76 Somebody To Love Queen 12:21 A 78 Beast Of Burden Rolling Stones 12:25 A 83 It's Raining Men Weather Girls 12:30 A 72 The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face Roberta Flack 12:31 A Tom's Diner Suzanne Vega 12:35 A Typical Male Tina Turner 12:39 A 93 Again Janet Jackson 12:42 A 75 Fox On The Run Sweet 12:46 A 74 Do It ('Til You're Satisfied) B.T. Express 12:53 A 75 Shining Star Earth, Wind & Fire ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 01:00 A 74 Can't Get Enough Bad Company 01:04 A 75 Island Girl Elton John 01:07 A 81 Slow Hand Pointer Sisters 01:11 A 67 Judy In Disguise (With Glasses) John Fred 01:16 A 77 You And Me Alice Cooper Page 1 032019.LOG 01:21 A 80 Fool In The Rain Led Zepplin 01:23 A 73 Hocus Pocus Focus 01:27 A 78 Hot Child In The city Nick Gilder 01:30 A 98 My Favorite Mistake Sheryl Crow 01:31 A 85 Saving All My Love For You Whitney Houston 01:35 A 72 Run Run Run Jo Jo Gunne 01:37 A Cradle Of Love Billy Idol 01:41 A 75 My Little Town Simon & Garfunkel 01:46 A 75 Wildfire Michael Murphey 01:49 A 77 Lucille Kenny Rogers ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 03/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 02:01 A 80 Funkytown Lipps, Inc. -

1 Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude the Beatles 1968

1 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 2 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 5 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 7 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 8 Peggy Sue Buddy Holly 1957 9 Imagine John Lennon 1971 10 Johnny B. Goode Chuck Berry 1958 11 Born In The USA Bruce Springsteen 1985 12 Happy Together The Turtles 1967 13 Mack The Knife Bobby Darin 1959 14 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 15 Blueberry Hill Fats Domino 1956 16 I Heard It Through The Grapevine Marvin Gaye 1968 17 American Pie Don McLean 1972 18 Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival 1969 19 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 20 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 21 Light My Fire The Doors 1967 22 My Girl The Temptations 1965 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 California Girls Beach Boys 1965 25 Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf 1968 26 Take It Easy The Eagles 1972 27 Sherry Four Seasons 1962 28 Stop! In The Name Of Love The Supremes 1965 29 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 30 Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley 1956 31 Like A Rolling Stone Bob Dylan 1965 32 Louie Louie The Kingsmen 1964 33 Still The Same Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1978 34 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 1956 35 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 36 Tears Of A Clown Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 1970 37 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer 1986 38 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 39 Layla Derek & The Dominos 1972 40 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 41 Don't Be Cruel Elvis Presley 1956 42 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 43 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 44 Old Time Rock And Roll Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1979 45 Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Presley 1956 46 Jump (For My Love) Pointer Sisters 1984 47 Little Darlin' The Diamonds 1957 48 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 49 Night Moves Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band 1977 50 Oh, Pretty Woman Roy Orbison 1964 51 Ticket To Ride The Beatles 1965 52 Lady Styx 1975 53 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 54 L.A. -

Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 10 April 2016 Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work Randy Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Randy (2016) "Billy Joel and the Practice of Law: Melodies to Which a Lawyer Might Work," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: Billy Joel and the Practice of Law BILLY JOEL AND THE PRACTICE OF LAW: MELODIES TO WHICH A LAWYER MIGHT WORK Randy Lee* Piano Man has ten tracks.1 The Stranger has nine.2 This work has seven melodies to which a lawyer might work. I. TRACK 1: FROM PIANO BARS TO FIRES (WHY WE HAVE LAWYERS) Fulton Sheen once observed, “[t]he more you look at the clock, the less happy you are.”3 Piano Man4 begins by looking at the clock. “It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday.”5 As “[t]he regular crowd shuffles in,” there’s “an old man” chasing a memory, “sad” and “sweet” but elusive and misremembered.6 There are people who pre- fer “loneliness” to “being alone,” people in the wrong place, people out of time, no matter how much time they might have.7 They all show up at the Piano Man’s bar hoping “to forget about life for a while”8 because, as the song reminds us, sometimes people can find themselves in a place where their life is hard to live with. -

Apple Label Discography

Apple Label Discography 100-800 series (Capitol numbering series) Apple Records was formed by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr in 1968. The Apple label was intended as a vehicle for the Beatles, their individual recordings and the talent they discovered. A great deal of what appeared on Apple was pretty self indulgent and experimental but they did discover a few good singers and groups. James Taylor recorded his first album on the label. Doris Troy recorded a good soul album and there are 2 albums by John Lewis and the Modern Jazz Quartet. The Beatlesque group Badfinger also issued several albums on the label, the best of which was “Straight Up”. Apple Records fell apart in management chaos in 1974 and 1975 and a bitter split between the Beatles over the management of the company. Once the lawyers got involved everybody was suing everybody else over the collapse. The parody of the Beatles rise and the disintegration of Apple is captured hilariously in the satire “All You Need Is Cash: the story of the Rutles”. The Apple label on side 1 is black with a picture of a green apple on it, black printing. The label on side 2 is a picture of ½ an apple. From November 1968 until early 1970 at the bottom of the label was “MFD. BY CAPITOL RECORDS, INC. A SUBSIDIARY OF CAPITOL INDUSTRIES INC. USA”. From Early 1970 to late 1974, at the bottom of the label is “MFD. BY APPLE RECORDS” From late 1974 through 1975, there was a notation under the “MFD. -

Strategic Intertextuality in Three of John Lennonâ•Žs Late Beatles Songs

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 11 July 2009 Strategic Intertextuality in Three of John Lennon’s Late Beatles Songs Mark Spicer Hunter College and City University of New York., [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Spicer, Mark (2009) "Strategic Intertextuality in Three of John Lennon’s Late Beatles Songs," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol2/iss1/11 This A Music-Theoretical Matrix: Essays in Honor of Allen Forte (Part I), edited by David Carson Berry is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. STRATEGIC INTERTEXTUALITY IN THREE OF JOHN LENNON’S LATE BEATLES SONGS* MARK SPICER his article will focus on an aspect of the Beatles’ compositional practice that I believe T merits further attention, one that helps to define their late style (that is, from the ground- breaking album Revolver [1966] onwards) and which has had a profound influence on all subsequent composers of popular music: namely, their method of drawing on the resources of pre-existing music (or lyrics, or both) when writing and recording new songs. -

Kentish Dialect

A Dictionary of the KENTISH DIALECT © 2008 KENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 'A Dictionary of the Kentish Dialect and Provincialisms: in use in the county of Kent' by W.D.Parish and W.F.Shaw (Lewes: Farncombe,1888) 'The Dialect of Kent: being the fruits of many rambles' by F. W. T. Sanders (Private limited edition, 1950). Every attempt was made to contact the author to request permission to incorporate his work without success. His copyright is hereby acknowledged. 'A Dictionary of Kentish Dialect and Provincialisms' : in use in the county of Kent by W.D.Parish and W.F.Shaw (Lewes: Farncombe,1888) Annotated copy by L. R. Allen Grove and others (1977) 'The Dialect of Kent in the 14th Century by Richard Morris' (Reprinted from Archaeologia Cantiana Vol VI, 1863) With thanks to the Centre for Kentish Studies, County Hall, Maidstone, Kent Database by Camilla Harley Layout and design © 2008 Kent Archaeological Society '0D RABBIT IT od rab-it it interj. A profane expression, meaning, "May God subvert it." From French 'rabattre'. A Dictionary of the Kentish Dialect and Provincialisms (1888)Page 11 AAZES n.pl. Hawthorn berries - S B Fletcher, 1940-50's; Boys from Snodland, L.R A.G. 1949. (see also Haazes, Harves, Haulms and Figs) Notes on 'A Dictionary of Kentish Dialect & Provincialisms' (c1977)Page 1 ABED ubed adv. In bed. "You have not been abed, then?" Othello Act 1 Sc 3 A Dictionary of the Kentish Dialect and Provincialisms (1888)Page 1 ABIDE ubie-d vb. To bear; to endure; to tolerate; to put-up-with. -

Christopher Teves Solo Guitar Repertoire List

Christopher Teves Solo Guitar Repertoire List Wedding Air On the G String Bach Air, from Water Music Handel Andante, from violin Sonata II Bach Andante, from Sonatina in A Torroba Amazing Grace Traditional Arioso, from Harpsichord concerto Bach Aylesford Gavotte Handel Bridal Chorus, from Lohengrin Wagner Canon in D Pachelbel Concerto in D, 1st movement, Allegro Vivaldi Concerto in D, 2nd movement, Largo Vivaldi Gavottes I & II from 6th Cello Suite Bach Greensleeves Anon. Gymnopedie #1 Satie Hornpipe, from Water Music Handel How Beautiful Twila Paris Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring Bach Joyful Joyful Beethoven Largo from Xerxes Handel Liebestraum Liszt Prelude #1, from Well Tempered Clavier Bach Prelude to the 1st Cello Suite Bach Prelude to the 4th Lute Suite Bach Raindrop Prelude Chopin Rondeau Mouret Saraband from the 1st Cello Suite Bach Saraband, from the violin sonata in B minor Bach Sheep May Safely Graze Bach Simple Gifts Shaker Hymn Sleepers Awake Bach The Spacious Firmament on High Haydn Spring, Theme from 1st movement Vivaldi Trumpet Tune Purcell Trumpet Voluntary Clark Wedding March, ( Midsummer Night’s Dream) Mendelssohn The Wedding Song, (There is Love) Hymns/Religious Amazing Grace, Traditional For the Beauty of the Earth, Traditional Fairest Lord Jesus, Traditional How Beautiful, Twila Paris Simple Gifts, Shaker Hymn Seek Ye First, Karen Lafferty Popular/Folk After the Goldrush Niel Young All You Need Is Love Beatles Annie’s Song John Denver Angel Jack Johnson Arthur’s Theme Bacharach, Sager, Cross, Allen Ashokan Farewell Payne -

Wayward Fool the Broad Street Maniac and the Vagabonds of Chester Alley: a Voyage Through the Mind of a ‘Half-Hazard’ Aristocrat

Wayward Fool The Broad Street Maniac and the Vagabonds of Chester Alley: A Voyage Through the Mind of a ‘Half-Hazard’ Aristocrat By Stylés Akira 2 3 Table of Contents Chapter One: The Making of a Man and All that One Could Ask .............................. 4 Part 1: How Huggsly Came to Be .................................................................................... 6 Part 2: Miranda and Clarke .......................................................................................... 17 Chapter Two: The Breaking of a Man and the Descent .............................................. 23 Scene 1: The Talbots’ Salon—Penelope and Huggsly ................................................. 25 Scene 2: The Sitting Room at Evergreen—The Calling and The Falling .................. 35 The WERTY Love Letters ............................................................................................. 42 Scene 3: The Cotillion ..................................................................................................... 44 Chapter Three: The Broad Street Maniac ................................................................... 50 Chapter Four: The Vagabonds of Chester Alley ......................................................... 61 Part E: The Party of Buffoons ....................................................................................... 67 Part 2: The Windfall ....................................................................................................... 72 Chapter Five: The Awakening ...................................................................................... -

The Butcher's Bill an Accounting of Wounds, Illness, Deaths, and Other Milestones Aubrey-Maturin Sea Novels of Patrick O'br

The Butcher’s Bill an accounting of wounds, illness, deaths, and other milestones in the Aubrey-Maturin sea novels of Patrick O’Brian by Michael R. Schuyler [email protected] Copyright © Michael R. Schuyler 2006 All rights reserved Page: 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 Combined Table of Ship and Book Abbreviations ...................................................... 9 Table of Commissions..................................................................................................... 9 Master & Commander ................................................................................................. 10 Table 1-1: Butcher’s Bill for Master & Commander .............................................. 18 Table 1-2: Crew of HMS Sophie .............................................................................. 20 Table 1-3: Met or mentioned elsewhere................................................................. 23 Post Captain .................................................................................................................. 24 Table 2-1: Butcher’s Bill for Post Captain .............................................................. 32 Table 2-2: Passengers and crew of Lord Nelson.................................................. 32 Table 2-3: Crew of HMS Polychrest........................................................................ 33 Table 2-4: Crew of HMS Lively ............................................................................... -

The Club of Queer Trades- G.K.Chesterton

The Club of Queer Trades by G.K.Chesterton Chapter 1 The Tremendous Adventures of Major Brown Rabelais, or his wild illustrator Gustave Dore, must have had something to do with the designing of the things called flats in England and America. There is something entirely Gargantuan in the idea of economising space by piling houses on top of each other, front doors and all. And in the chaos and complexity of those perpendicular streets anything may dwell or happen, and it is in one of them, I believe, that the inquirer may find the offices of the Club of Queer Trades. It may be thought at the first glance that the name would attract and startle the passer-by, but nothing attracts or startles in these dim immense hives. The passer-by is only looking for his own melancholy destination, the Montenegro Shipping Agency or the London office of the Rutland Sentinel, and passes through the twilight passages as one passes through the twilight corridors of a dream. If the Thugs set up a Strangers' Assassination Company in one of the great buildings in Norfolk Street, and sent in a mild man in spectacles to answer inquiries, no inquiries would be made. And the Club of Queer Trades reigns in a great edifice hidden like a fossil in a mighty cliff of fossils. The nature of this society, such as we afterwards discovered it to be, is soon and simply told. It is an eccentric and Bohemian Club, of which the absolute condition of membership lies in this, that the candidate must have invented the method by which he earns his living.