In New York City Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The City Record the Comptrollers Report on Status of Existing Capital Projects on July 1, 2015, 108 Pages

SUPPLEMENT TO THE CITY RECORD THE COMPTROLLERS REPORT ON STATUS OF EXISTING CAPITAL PROJECTS ON JULY 1, 2015, 108 PAGES VOLUME CXLII NUMBER 229 TUESDAY, DECEMBER 1, 2015 Price: $4.00 Purchasing Management � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4664 Finance ��������������������������������������������������������� 4665 THE CITY RECORD TABLE OF CONTENTS Agency Chief Contracting Officer � � � � � � � 4665 Housing Authority ��������������������������������������� 4665 BILL DE BLASIO PUBLIC HEARINGS AND MEETINGS Human Resources Administration ������������� 4665 Mayor Contracts � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4665 Borough President - Queens ����������������������� 4657 STACEY CUMBERBATCH Information Technology and City Council . 4658 Commissioner, Department of Citywide City Planning Commission ������������������������� 4658 Telecommunications. 4665 Administrative Services Community Boards . 4659 Parks and Recreation . 4665 Housing and Community Renewal . 4659 Revenue � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4666 ELI BLACHMAN Office of Labor Relations ����������������������������� 4660 Police ������������������������������������������������������������� 4666 Editor, The City Record Landmarks Preservation Commission . 4660 Contract Administration Unit � � � � � � � � � 4666 Mayor’s Office of Contract Services . 4661 Published Monday through Friday except legal Transportation ��������������������������������������������� 4661 CONTRACT AWARD HEARINGS Administration for Children’s Services . 4666 holidays by the New York City -

Thanks to the Schools and Organizations Who Have Submitted Their 2017 Reports!

Thanks to the Schools and Organizations Who Have Submitted Their 2017 Reports! A. Philip Randolph Campus High School-06M540 Academy for Scholarship and Entrepreneurship: A College Board School-11X270 Academy of Finance and Enterprise-24Q264 Academy of Medical Technology: A College Board School-27Q309 Alfred E. Smith Career and Technical Education High School-07X600 Aviation Career & Technical Education High School-24Q610 Belmont Preparatory High School-10X434 Benjamin N. Cardozo High School Bronx Academy of Health Careers-11X290 Bronx Collaborative High School-10X351 Bronx Envision Academy-12X511 Bronx River High School-08X349 Bronx River High School-08X349 Bronx Theatre High School-10X546 Celia Cruz Bronx High School of Music, The-10X442 Civic Leadership Academy-24Q293 Claremont International HS-09X564 Cobble Hill School of American Studies-15K519 Concord High School-31R470 Corinth High School Dansville High School DreamYard Preparatory School-09X329 EBC High School for Public Service - Bushwick-32K545 Edward A. Reynolds West Side High School-03M505 Emma Lazarus High School for English Language Scholars Epic High School - South-27Q314 Expeditionary Learning School for Community Leaders-21K572 Flushing High School-25Q460 Fordham High School for the Arts-10X437 Fordham Leadership Academy-10X438 Fordham Leadership Academy-10X438 Forest Hills High School-28Q440 Franklin D. Roosevelt High School Frederick Douglass Academy II Secondary School-03M860 Gilbertsville-Mount Upton CSD Gloversville High School Grover Cleveland High School-24Q485 -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

New Century High Schools Dear New Yorkers, for Too Long New York City’S High Schools Have Not Prepared Even a Majority of Students for Graduation

New Visions for Public Schools 320 West 13th Street New York, NY 10014 Phone (212) 645-5110 Fax (212) 645-7409 www.newvisions.org new century high schools Interim Report Card Report Interim and the small schools movement in New York City new century high schools Dear New Yorkers, For too long New York City’s high schools have not prepared even a majority of students for graduation. There is no single solution to the problems confronting our schools, but we need to do better—and we can. Over the past several years, New York City has undertaken a far-reaching process of education reform. This report describes one of the most exciting aspects of this reform, the creation of innovative, new small high schools as part of the New Century High Schools Initiative. We have worked closely with New Visions for Public Schools to involve thousands of New Yorkers who STRATEGY deeply care about our children’s education. This initiative represents the best Spurring innovation and of what New York City can be. expanding educational options 3 Four years into a decade-long process, the New Century High Schools Initiative has created a portfolio of 75 new small high schools, with 15 more TIMELINE opening in 2005 and 2006, using a selective process that incorporates Work to date 10 everything we know about what works in education—rigorous and relevant curricula, strong parent and community involvement and greater personal RESULTS attention for every child. These new schools are preparing New York City Building momentum for change 13 students to meet the challenges of higher education, work and citizenship CONCLUSION in the 21st century. -

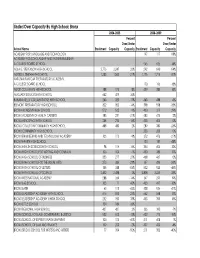

Under/Over Capacity by High School: Bronx

Under/Over Capacity By High School: Bronx 2004-2005 2008-2009 Percent Percent Over/Under Over/Under School Name Enrollment Capacity Capacity Enrollment Capacity Capacity ACADEMY FOR LANGUAGE AND TECHNOLOGY 197 117 68% ACADEMY FOR SCHOLARSHIP AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A COLLEGE BOARD SCHOOL 546 636 -14% ADLAI E. STEVENSON HIGH SCHOOL 2,773 2,247 23% 292 640 -54% ALFRED E. SMITH HIGH SCHOOL 1,243 1,564 -21% 1,176 1,716 -31% ANTONIA PANTOJA PREPARATORY ACADEMY, A COLLEGE BOARD SCHOOL 170 196 -13% ASTOR COLLEGIATE HIGH SCHOOL 188 174 8% 439 385 14% AUXILIARY SERVICES HIGH SCHOOL 642 479 34% BANANA KELLY COLLABORATIVE HIGH SCHOOL 266 320 -17% 465 488 -5% BELMONT PREPARATORY HIGH SCHOOL 302 352 -14% 398 598 -33% BRONX ACADEMY HIGH SCHOOL 512 565 -9% 400 311 29% BRONX ACADEMY OF HEALTH CAREERS 183 231 -21% 483 474 2% BRONX AEROSPACE HIGH SCHOOL 248 294 -16% 405 404 0% BRONX COALITION COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL 488 480 2% 289 389 -26% BRONX COMMUNITY HIGH SCHOOL 203 203 0% BRONX ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY 106 116 -9% 372 473 -21% BRONX HAVEN HIGH SCHOOL 104 181 -43% BRONX HEALTH SCIENCES HIGH SCHOOL 98 116 -16% 354 404 -12% BRONX HIGH SCHOOL FOR WRITING AND COMMUN 103 104 -1% 450 385 17% BRONX HIGH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS 353 277 27% 468 467 0% BRONX HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE VISUAL ARTS 273 386 -29% 367 496 -26% BRONX HIGH SCHOOL OF LETTERS 156 348 -55% 502 923 -46% BRONX HIGH SCHOOL OF SCIENCE 2,492 2,438 2% 2,808 2,249 25% BRONX INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY 288 334 -14% 347 291 19% BRONX LAB SCHOOL 103 71 45% 423 497 -15% BRONX LATIN 63 113 -44% 308 526 -41% -

Nycsmall High Schools

SMALL SCHOOLS. BIG CHOICES. Explore the Possibilities. 2005–2006 Guide to small NYChigh schools in collaboration with Made possible by the Small Schools. Big Choices. Explore the possibilities. Congratulations. As an eighth grade student, you are about to make one of the most important choices in your academic career—you are about to choose a high school. You are in luck. New York City has more than 300 high schools from which you and your family can choose. Each is different. They offer a wide range of classes, programs, and activities. Great high schools in our City engage you in difficult and challenging course work in safe and respectful envi- ronments. They prepare you for life after high school, going to college and getting a good job. New Visions for Public Schools has put together The New York City Guide to Small High Schools to describe new opportunities in the public high school system: over 200 small secondary schools created over the last five years. These small schools are part of the Department of Education’s efforts to create more choices for thousands of students like you so that you can succeed as citizens of New York City. Nearly 50 of the schools described in this Guide are new. They have been created by over 225 different organizations, including New Visions for Public Schools, the Asia Society, City University of New York, The College Board, The Institute for Student Achievement, International Partnership Schools, the New York City Outward Bound Center, Replications and The Urban Assembly. What is special about these small schools? Most enroll 500 or fewer students. -

High School Report.Pub

SMALL SCHOOLS, FEW CHOICES: How New York City’s High School Reform Effort Left Students With Disabilities Behind A Report Issued by Parents for Inclusive Education Prepared by Kim Sweet, Associate General Counsel New York Lawyers for the Public Interest NYLPI ABLE OF ONTENTS T C Acknowledgments i Executive Summary 1 Introduction 5 The Special Education System Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) 8 The Special Education System in New York City 9 Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act 11 Findings Components of the DOE’s High School Reform Plan 12 Enrollment Data 13 Policy Allowing New Schools to Exclude Students with Disabilities 16 Failure to Offer Required Programs 19 Diminished Access to Choice 21 Total Lack of Choice for District 75 Students 23 Failure to Coordinate with the IEP Process 26 Inadequate Information and Guidance 27 Problems with Preparation of New, Small Schools 30 Conclusions and Recommendations 32 Appendix A Schools Surveyed in March and April 2006 36 Appendix B High Schools Listed in the 2005-2006 High School Directory 37 Appendix C High Schools Listed in the 2006-2007 High School Directory 45 Appendix D Glossary of Acronyms 53 Published in October 2006 CKNOWLEDGMENTS A his report was researched and written with funding provided by the New T York State Commission on Quality of Care and Advocacy for Persons with Disabilities through its Protection and Advocacy program. Parents for Inclusive Education would like to thank Commission staff for their support. We also would like to thank Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom for printing the report pro bono. -

View Fall 2014 Nyfoodstory

Rebecca Turner, ‘famous cook’ of Eastchester One historian’s quest to learn about a long-forgotten slave and the mores and foodways of her time Photo by Larry H. Spruill Editor’s Note: Larry H. Spruill received a CHNY’s Scholar’s Grant for 2012 to underwrite his research on the freed slave, Rebecca Turner, her family and their foodways. This is an account of some of his research. By Larry H. Spruill in the shadow of old St. Paul’s Church. The old homestead of her family, built over a century ago, is among the interesting curiosities Rebecca Turner, a well-known cook in 19th-century Eastchester, Eastchester and its quaint villages New York, was all but forgotten. In 2012 her gravesite was posi- are synonymous with the best of its kind in that vicinity. ‘Aunt Mary’s’ tively identified near her daughter Emmeline Turner-Pierce’s qualities of American suburban life, mother, who was known throughout that faded marble headstone. Rebecca’s name was inscribed on a region as ‘Aunt Becky Turner’ had been a slave tombstone for public viewing as part of St. Paul’s Church and symbolizing middle class comforts and Cemetery National Historic Site. in early life … for many years she was a abundance. Suggestions of historical con- famous cook in service at Guion’s Tavern…”1 their names, ages, hints of education nections between its modern self-image Rebecca Turner, “a famous cook,” and the deceased matriarch’s occupa- and African slavery are usually met with Mary Turner-Treadwell and her niece, tion. More than 100 years later, these disbelief and even ridicule. -

Transfer High School Data from NYC Department of Education

Number of Students That Transferred Sending into Transfer Schools DBN Sending School Name 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 01M448 University Neighborhood High School 13 12 s 01M509 Marta Valle High School 15 7 11 02M047 47 The American Sign Language and English Secondar s 8 s 02M135 The Urban Assembly School for Emergency Management s s 7 02M139 Stephen T. Mather Building Arts & Craftsmanship Hi s s 8 02M282 Urban Assembly Maker Academy s s 9 02M288 Food and Finance High School 21 17 13 02M294 Essex Street Academy s 10 15 02M296 High School of Hospitality Management 9 13 9 02M298 Pace High School 9 11 20 02M300 Urban Assembly School of Design and Construction, 8 12 13 02M303 Facing History School, The 10 11 11 02M305 Urban Assembly Academy of Government and Law, The 9 18 14 02M308 Lower Manhattan Arts Academy 29 16 18 02M316 Urban Assembly School of Business for Young Women, 37 20 15 02M374 Gramercy Arts High School 19 12 10 02M376 NYC iSchool s s 7 02M392 Manhattan Business Academy 12 22 11 02M393 Business Of Sports School 23 24 15 02M399 The High School For Language And Diplomacy 7 8 8 02M400 High School for Environmental Studies 33 52 47 02M419 Landmark High School 10 s 10 02M420 High School for Health Professions and Human Servi 36 28 36 02M422 Quest to Learn 11 9 8 02M425 Leadership and Public Service High School 15 26 14 02M427 Manhattan Academy For Arts & Language 10 7 14 02M437 Hudson High School of Learning Technologies 6 17 9 02M449 Vanguard High School 7 6 10 02M475 Stuyvesant High School s 6 s 02M489 High School of Economics and Finance 24 23 19 02M507 Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology 6 12 7 02M519 Talent Unlimited High School 8 s s 02M520 Murry Bergtraum High School for Business Careers 18 10 10 02M529 Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis High School 25 23 22 02M533 Union Square Academy for Health Sciences 10 s 9 02M534 Harvest Collegiate High School s s 7 02M542 Manhattan Bridges High School s 16 s 02M543 New Design High School 16 9 11 02M551 Urban Assembly New York Harbor School 11 6 12 02M580 Richard R. -

Hazardous Materials

FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT FOR THE CROTON WATER TREATMENT PLANT AT THE HARLEM RIVER SITE 7.13. HAZARDOUS MATERIALS.................................................................................... 1 7.13.1. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1 7.13.2. Baseline Conditions ................................................................................................ 1 7.13.2.1. Existing Conditions......................................................................................... 1 7.13.2.2. Future Without the Project............................................................................ 82 7.13.3. Potential Impacts................................................................................................... 83 7.13.3.1. Potential Project Impacts .............................................................................. 83 7.13.3.2. Potential Construction Impacts..................................................................... 91 FIGURE 7.13-1. 1895 ARTISTIC RENDERING HARLEM RIVER SITE ................................ 4 FIGURE 7.13-2. 1897 TOPOGRAPHIC MAP HARLEM RIVER MAP..................................... 5 FIGURE 7.13-3. 1941 AERIAL PHOTOGRAPH HARLEM RIVER SITE................................ 6 FIGURE 7.13-4. FEBRUARY 1954 AERIAL PHOTOGRAPH HARLEM RIVER SITE.......... 7 FIGURE 7.13-5. APRIL 1954 AERIAL PHOTOGRAPH HARLEM RIVER SITE ................... 8 FIGURE 7.13-6. 1950S AERIAL PHOTOGRAPH HARLEM -

Nor News Template

Serving Norwood, Bedford Park, Fordham and University Heights NORWOOD NEWS Vol. 25, No. 14 ■ PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION ■ July 12 –25, 2012 DANCING IN THE HEAT Espaillat Cries Foul, Clouding Election Result By ALEX KRATZ On primary election night two weeks ago, Adriano Espail - lat, a state senator looking to become the first Dominican-born member of Congress, thanked his supporters and acknowl - edged that they had fallen just short of defeating longtime incumbent Charlie Rangel for the new 13th Congressional Dis - trict seat, which now includes a piece of the northwest Bronx. As the Board of Election continued to tally votes the next day, however, Rangel’s lead narrowed significantly. It eventual - ly dropped to 802 votes or about 2 percent of the total vote. On top of the new numbers, Espaillat’s camp says it began hear - ing reports of voter suppression and irregularities in the vote count. Last week, seven days after conceding, Espaillat filed a law - suit against the Board of Elections calling on an outside mon - itor to oversee the final vote count and secure the ballots in case a recount was needed. A judge ultimately ordered the BOE to retain copies of all the ballots and said the court would Photo by Adi Talwar have to certify election results before they were sent to the KIDS TAKE ADVANTAGE of a fire hydrant shower outside of Williamsbridge Oval Park last week during state Board of Elections. That certification would not take a scorching heat wave around the Independence Day holiday. place until at least Wednesday, July 11, after the Norwood News went to press. -

Location Code DBN School Name M040 02M040 P.S. 040 Augustus Saint-Gaudens M142 01M142 P.S

Location Code DBN School Name M040 02M040 P.S. 040 Augustus Saint-Gaudens M142 01M142 P.S. 142 Amalia Castro K953 19K953 The East New York Arts and Civics High School K284 23K284 The Gregory Jocko Jackson School of Sports, Art, and K898 16K898 The Brooklyn Green School K907 19K907 Legacy School of the Arts Q376 26Q376 P.S. 376 Q384 30Q384 P.S. 384 M184 01M184 P.S. 184m Shuang Wen M064 01M064 P.S. 064 Robert Simon M020 01M020 P.S. 020 Anna Silver Q379 25Q379 College Point Collaborative K936 20K936 MS 936 Arts Off 3rd Q390 26Q390 The CIVIC School of Bayside Hills M140 01M140 P.S. 140 Nathan Straus X595 12X595 P.S. 595 Q398 30Q398 The Hector Figueroa School M134 01M134 P.S. 134 Henrietta Szold M310 04M310 The Judith S. Kaye School X593 09X593 South Bronx International Middle School K896 15K896 The School of Creativity and Innovation M034 01M034 P.S. 034 Franklin D. Roosevelt X596 75X596 P.S. X596 K889 22K889 P.S. 889 M110 01M110 P.S. 110 Florence Nightingale K938 19K938 P.S. 938 K915 13K915 I.S. 915 M297 02M297 M.S. 297 X594 09X594 M.S. 594 X360 10X360 P.S. 360 K253 21K253 P.S. 253 X584 07X584 I.S. 584 K890 22K890 M.S. 890 X625 07X625 Walkabout Bronx High School M063 01M063 The STAR Academy - P.S.63 Q377 27Q377 P.S. 377 X583 08X583 P.S. 583 M188 01M188 P.S. 188 The Island School K939 20K939 Sunset School of Cultural Learning M371 05M371 School of Earth Exploration and Discovery Harlem (S M015 01M015 P.S.