1CCEE6 24 (REV) INSTRUCTION CF HIGH Sum STUCENTS in REACING for DIFFERENT PLRPOSE: SMITH, HELEN K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farmers Markets in the Berkshire Grown Region

Guide to 2020 Local Food arms FARMERS MARKETS • FARM STANDS F • FARMS • RESTAURANTS & 16 2 14 18 12 17 20 27 A 7 8 VERMONT Petersburg 2 9 23 19 22 D FARMS: see pg 6 -14 Williamstown B C 2 FARMERS MARKETS: see pg 4-5 26 25 North 7 Adams 21 8 3 8 Florida 8A 6 22 NORTH 7 13 4 Cherry Plain 5 11 28 2 Charlemont 15 Adams 43 New Ashford 8A 24 116 1 43 Savoy Cheshire 10 Stephentown 7 8A 53 30 E 63 66 37 56 70 Hancock 48 8 57 Plaineld 32 Lanesborough 686369 Windsor N E W Y O R K 8A 65 40 22 F 52 West 20 68 60 29 Cummington 54 Dalton 62 G H Cummington 20 58 New 46 CENTRAL Lebanon Hinsdale 44 Piseld 36 50 Peru 43 33 7 59 41 45 42 49 22 47 Canaan 51 BERKSHIRE Worthington 64 295 112 41 COUNTY 38 31 35 61 Richmond 55 67 43 Lenox 7 Washington I 39 7A 34 Middleeld 20 Becket y a West 94 w 108 k 104 91 r Stockbridge a 203 P O 88 e Spencertown t a 75 t Austerlitz Lee 8 S 90 ic n o c 22 20 a Chester 112 T Stockbridge 41 78 93 83 7 102 80 20 183 127 Housatonic Tyringham 128 90 Alford 119 M 106 8 115 92 71 85 86 Otis 121 Great L 73 Q 109 99 Barrington 23 S Blandford Hillsdale 23 Monterey 105 23 123 125 N Egremont 90 124 97 22 100 57 111 7 107 SOUTH 126 New Marlborough Sandiseld 82 U 8 74 71 Sheeld 110 98 122 57 89 81 102 72 Tolland 113 103 116 95 57 120 41 Ashley 7A 76 Falls 272 77 Canaan 183 79 114 J 41 CONNECTICUT P 117 84 T 112 7 K 44 96 R 118 101 44 Welcome to the 2020 Berkshire Grown Guide to Local Food & Farms! Now more than ever, connections to local food and farms hold our community together. -

Corporate Sponsorship Packet 2020.Indd

2020 Corporate Sponsorship Opportunities REACH YOUR AUDIENCE AND SUPPORT OUR MISSION Sponsorship Levels Boscobel House and Gardens is famous for preserving and sharing the matchless beauty of our iconic Hudson River site, BUSINESS historic house, and museum collection. Each year Boscobel serves more than 26,000 neighbors and guests with guided MEMBERSHIP tours, community events, and fun and educational programs for families and schools. INCLUDES: Listing on Boscobel’s website plus A major contributor to the local economy, Boscobel welcomes 81,000 visitors annually, employs a seasonal staff of 40, business membership card granting prioritizes local vendors, and highlights local products in its Design Shop. In addition, the museum hosts hundreds of admission for the bearer plus up to local vendors and employees of its non-profi t tenant/partners, the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival and Cold Spring three guests of any age to include a Farmers’ Market. guided tour of the Historic House Corporate sponsors are key partners in Boscobel’s mission to engage diverse audiences in the Hudson Valley’s ongoing, Museum, access to the grounds dynamic exchange between design, history, and nature. Your sponsorship support helps make Boscobel everyone’s and seasonal exhibitions, and a 10% home on the Hudson, and connects our growing audience to your business. discount in the Design Shop for all guests in the passholder’s party. One-time use of Boscobel’s private meeting room $500 space (Based on availability, capacity 70) Print ad in local papers Print -

Fund-Raising Texas Chef Gets a Taste of New Mexico Print | Email This Story

Last Update Search All Contact Us | Register/Login | Site Map Tue Jun 14, 2005 11:44 am Subscribe Print or eNewMexican | NM Jobs | Real Estate - Virtual Tours | Display Ads | Directory | Classifieds | Advertise | Archives News: Santa Fe / NM, Communities 26 page replica of the daily Fund-raising Texas chef gets a taste of New Mexico print | email this story MICHELLE PENTZ GLAVE | The New Mexican October 27, 2004 Like a true Texas cowpoke, Tim Love rode into the Española Farmers' Market on Columbus Day to the cheers and waves of the 20-some farmers huddled under plastic-wrapped booths. And despite the relentless downpour of frigid rain, one called out, "Welcome to - New Mexico!" Most Read News Kids swarmed the posse of horses, Recent Comments Death Notices showing off their oversized, gnarled sugar Crime / Police Notes beets, carrots, apples and squash entered Editorial in the day's "biggest and oddest vegetable" Letters to Editor Columns contest. Weather Topic List You'd think the heroes of the day were Love --an award-winning chef hailing from the Fort Worth Stockyards -- and his sidekick, Santa Fe's world-famous Visitors Guide author of Southwestern cuisine, the Coyote Café's Mark Miller. But once the Hotel Search Food Network cameras started rolling and the unassuming Love got started New Mexican Guides Residents Guide chatting with each grower, asking questions, chomping on chicos and chiles, Supplements listening to descriptions of the area's specialty produce and how to prepare each, it Spirituality / Support became clear: The stars of the day were the local farmers. Restaurants Sure, Love had come to Española on this October "trail ride" as part of his eight- Reader Photos day quest to raise money for Spoons Across America, a James Beard Foundation- Submit a Photo Our Week in Pictures supported program that educates kids on healthy eating, nutritious cooking and the Special Projects back-to-basics idea of using the dinner table for family time. -

The Apple Farm!

“Part of the secret of success in life is to eat what you like and let the food fight it out inside.” -Mark Twain SEPTEMBER - OCTOBER 2013 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Greetings from the GM ............2 The Apple Farm! ........................3 Words on Wellness ...................4 Words on Wine ..........................5 Autumn on Your Plate ..........6-7 Upcoming Events ......................8 Staff Updates .............................9 Member-Owner Give-Away ...10 Kids Classes .............................10 Owner-to-Owner ......................11 New Sale Signage ...................11 Co-op Calendar ....................... 12 he Apple Farm in Philo is a staple in our produce department at Ukiah Natural Foods. We are Tgrateful every fall for the twenty-plus varieties that are provided during the peak of apple sea- son for our customers’ enjoyment! It was the cold wet winter of 1984 when Tim Bates and Karen Schmitt began taming the wild property that is now their apple farm. Today, more than 3 genera- tions join together to care for The Apple Farm and this family affair is one that is enjoyed by all! “Our years of working the farm led us from conventional practices, through transi- tion, and on to many years of being certified organic. We want to continue to evolve and have chosen biodynamic farming as a framework in which we can further de- velop our relationship with our farm. It is an endlessly fascinating endeavor and we are all energized by the new and old ideas that we unearth.” - from www.philoapplefarm.com Tim, Karen and family produce a wide variety of products beyond their apples. The delicious, delec- table apples that they grow later become apple syrup, apple cider vinegar and hard apple cider, to name a few. -

Epic-Wine-Menu-08.20.21-Docx.Pdf

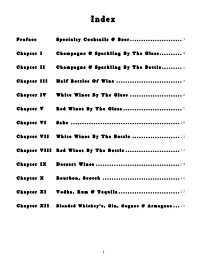

I n d e x P r e f a c e Specialty Cocktails & Beer ....................... 3 C h a p t e r I Champagne & Sparkling By T h e G l a s s .......... 4 C h a p t e r II Champagne & Sparkling By T h e B o t t l e ......... 6 Chapter III Half Bottles Of Wine ............................. 7 C h a p t e r I V White Wines By T h e G l a s s ....................... 8 C h a p t e r V R e d W i n e s By T h e G l a s s .......................... 9 C h a p t e r V I S a k e ................................................ 10 Chapter VII White Wines By T h e B o t t l e ..................... 1 2 Chapter VIII R e d W i n e s By T h e B o t t l e ........................ 1 7 C h a p t e r I X Dessert Wines ..................................... 2 4 C h a p t e r X Bourbon, Scotch .................................. 2 6 C h a p t e r X I V o d k a , R u m & T e q u i l a ........................... 2 7 Chapter XII B l e n d e d W h i s k e y ’ s , Gin, Cognac & Armagnac ... 2 8 1 “Come quickly, I am drinking the stars!” {DOM PÉRIGNON} UPON TASTING THE FIRST SPARKLING CHAMPAGNE 2 c o c k t a i l s & b E E R PREFACE SPECIALTY COCKTAILS & BEER S ea sona l C oc kt a il s IPA’s “A WRINKLE IN TIME” ....................................................... -

First Night First Night

what to do • where to go • what to see December 19,2005–January 1,2006 ThTheeeOfO Offficficiaiaiall GuidGuideeetot too BOSTBOSTONON Boston’s 9 Best Bets for Ringing in the New YYearear Including: Our Guide to First Night PLUS: >What’s New in the New YearYear >Q&A with the Boston Pops’ Keith Lockhart www.panoramamagazine.com Now in our 2nd d Breaking Year!!! contents Recor COVER STORY 15 Countdown 2006 From First Night to rockin’ parties, our guide to the best places to ring in the New Year ® FEATURE 18 The Hub It Is A-Changin’ The Hilarious Celebration of Women and The Change! Panorama takes a look at what’s new in Boston in 2006 in 2006 DEPDEPARTMENTSARTMENTS 6 around the hub 6 news & notes 12 nightlife 10 on exhibit 13 dining Men 11 kids corcornerner 14 style Love It Too!!! 22 the hub directory 23 currentcurrent events TIP TOP: TheThe TopTop ofof thethe HubHub 31 clubs & bars atat thethe PrudentialPrudential CenterCenter,, where LauraLaura enjoysenjoys champagne,champagne, is is oneone 33 museums & galleries ofof manymany ggreatreat locationslocations toto 38 maps celebratecelebrate 20062006 asas thethe clockclock “YOU’LL LOVE IT. IT’S 43 sightseeing strikesstrikes midnight.midnight. Refer to story, pagepage 15.15. 48 frfreedomeedom trail PPHOTOHOTO BY HILARIOUS. GO SEE IT!” 50 shopping JOHNSAVONEJOHNSAVONE..COM - Joy Behar, The View 54 mind & body 55 rrestaurantsestaurants on the cover: 68 NEIGHBORHOODS “FRESH, FUNNY & SIMPLY Model Ashley of Maggie Inc. 78 5 questions with… gets ready for a rrollickingollicking New Year’s Eve at Top of the Hub. TERRIFIC!” Boston Pops maestro Photo: johnsavone.com KEITH LOCKHARTLOCKHART Photo: johnsavone.com - LA Times Hair: Rogue, Salon Marc Harris Great Rates For Groups! To reserve call (617) 426-4499 ext. -

A Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

HOW ARE WE ALL CONNECTED? A written creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree As Master of Fine Arts 50 In Zo'Z Creative Writing • U 2 C , by Jennifer Lewis San Francisco, California May 2015 Copyright by Jennifer Lewis 2015 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read How Are We All Connected by Jennifer Lewis, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master’s of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Peter Omer, MFA Professor of Creative Writing --------- Maxine Chemoff, MA Professor of Creative Writing How Are We All Connected? Jennifer Lewis San Francisco, California 2015 This short story collection explores the complexity of human behavior and how various people only see role or mask of a whole self. The characters are intentionally inconsistent. For example in “My Collection,” Elaine is speaking directly to someone. Maybe a close friend? Maybe her own conscience? The tone of her voice and her opinions are very different than in “A Distinguished Man,” where she is shown as a responsible and loving mother. These jumps in voice and point of view, illustrate how we all teetering between hypocrisy and compassion. I certify that the abstract is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. Chair, Thesis Committee Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Peter Omer, Maxine Chemoff, Shadia Savo and Jason Pontin. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

University Catering Menu

UNIVERSITY CATERING MENU TABLE OF CONTENTS OUR STAFF 05 Breakfast Andrea Green Catering Manager 08 Lunch 701.777.4435 | [email protected] Andrea grew up in a small town in southeast Michigan and has always had a love of cooking, baking, and food. After high school, Andrea 11 Buffets attended Michigan State University and graduated with a B.S. in Dietetics. Her career in food service began as a student employee 14 Served at MSU in the cafeteria. In 2007 Andrea moved to Grand Forks and began working for Dining Services as a Catering Supervisor, was 19 Hors D’oeuvres later was promoted to Barista Supervisor, and then in 2010, she was promoted to Catering Manager. Her favorite thing about being 22 Breaks the catering manager is the variety. She says, “Every event I plan and every day is unique and exciting.” Andrea brings 18 years of catering and food service experience, organization, creativity, and 24 Beverages passion to the UND catering team. When not working Andrea enjoys 26 Desserts spending quality time with her husband and three young boys. 28 Carry Out Beth Spitsberg Catering Sales Coordinator 33 Bakery 701.777.2256 | [email protected] Beth grew up in Grand Forks, ND and has always had a love of 37 Rentals UND. She began working at UND in 2015 and was promoted to the Catering Sales Coordinator in 2017. Beth has 31 years of 39 Guidelines customer service experience, a great menu planning experience, and, of course, a passion for food. Her favorite thing about working with University Catering is the great team of people she works with. -

Taap Cover and Title

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rowles, Kristin L.; Henehan, Brian M.; White, Gerald B. Working Paper Thinking Afresh About Processing: An Exploration of New Market Opportunities for Apple Products Staff Paper, No. SP 2001-03 Provided in Cooperation with: Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University Suggested Citation: Rowles, Kristin L.; Henehan, Brian M.; White, Gerald B. (2001) : Thinking Afresh About Processing: An Exploration of New Market Opportunities for Apple Products, Staff Paper, No. SP 2001-03, Cornell University, Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Ithaca, NY This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/23477 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

DECEMBER 2017 2017 DECEMBER Vol

by Lisa Hogan, Chair, Weavers Way close to our Ambler store. Aldi is reportedly BOARD Leadership Committee planning a huge growth phase, and home gro- 2018 CORNER Who ‘s cery and prepared-meal delivery services are EAVERS WAY IS SEEKING A FEW proliferating. Big-box stores such as Walmart Wmember-owners to join the Co-op and Target are now our competitors in the Running? Board of Directors in 2018. Next year will fresh and local food business. be a busy and exciting time to join the Board. The Board, according to our bylaws, The Philadelphia area grocery scene is chang- must have a minimum of nine and a maxi- Could Be You! ing quickly with Amazon taking over Whole Foods and opening a store in Spring House, (Continued on Page 31 BOARD ELECTIONS Community-Owned, The Shuttle Open to Everyone DECEMBER 2017 Since 1973 | The Newsletter of Weavers Way Co-op Vol. 45 | No. 12 Mayor Kenney Looking Ahead Talks Schools, To Giving Sustainability Twosdays 2018 by Crystal Pang, At Fall GMM Weavers Way Marketing Director by Jacqueline Boulden, OMMITTEES ARE A BIG PART OF HOW for the Shuttle CWeavers Way members can get engaged with the Co-op in a meaningful way. In 2018, DDRESSING AN OVERFLOW CROWD we are planning to support our committees by Aat last month’s Fall General Mem- raising awareness of their amazing work and bership Meeting, Philadelphia Mayor Jim by giving them an opportunity to raise money Kenney said he came to praise what the for causes that are important to them. -

Blues Lyric Formulas in Early Country Music, Rhythm and Blues, and Rock and Roll *

Blues Lyric Formulas in Early Country Music, Rhythm and Blues, and Rock and Roll * Nicholas Stoia NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.4/mto.20.26.4.stoia.php KEYWORDS: blues, country music, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, lyric formulas ABSTRACT: This article briefly recounts recent work identifying the most common lyric formulas in early blues and then demonstrates the prevalence of these formulas in early country music, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll. The study shows how the preference for certain formulas in prewar country music—like the preference for the same formulas in prewar blues—reflects the social instability of the time, and how the de-emphasis of these same formulas in rhythm and blues and rock and roll reflects the relative affluence of the early postwar period. This shift in textual content is the lyrical counterpart to the electrification, urbanization, and growing formal complexity that mark the transformation of prewar blues and country music into postwar rhythm and blues and rock and roll. DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.4.8 Received May 2018 Volume 26, Number 4, November 2020 Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory [0.1] Singers and songwriters in many genres of American popular music rely on lyric formulas for the creation of songs. Lyric formulas are fragments of lyrical content—usually lines or half lines— that are shared among singers and recognized by both musicians and listeners. Blues is the genre for which scholars have most conclusively established the widespread use of lyric formulas, and this study briefly recounts recent work that identifies the most common lyric formulas in commercially recorded blues from the early 1920s to the early 1940s—research showing that the high frequency of certain formulas reflects the societal circumstances of much of the African American population during that period.