Assessing and Treating Depression in Palliative Care Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Results Annual

2004 Results Annual BURGER KING TALL BLACKS Australia In New Zealand (Jeep International Series) Players Ed Book (Nelson Giants), Craig Bradshaw (Winthrop University), Dillon Boucher (Auckland Stars), Pero Cameron (Waikato Titans), Mark Dickel (Fenerbache), Paul Henare (Hawks), Mike Homik (Auckland Stars), Phill Jones (Nelson Giants), Troy McLean (Saints), Aaron Olson (Auckland Stars), Brendon Polyblank (Saints), Tony Rampton (Cairns Taipans), Christopher Reay (Southern Methodist University), Lindsay Tait (Auckland Stars), Paora Winitana (Hawks) Coach: Tab Baldwin Assistant Coach: Nenad Vucinic Video Coach: Murray McMahon Managers: Tony Henderson Physiotherapist: Dave Harris Results Lost to Australia 60-90 at Hamilton (Pero Cameron 15, Phill Jones 10) Beat Australia 80-75 at Christchurch (Phill Jones 18, Ed Book 17, Pero Cameron 10) Lost to Australia 79-90 at Invercargill (Pero Cameron 19, Phill Jones 19, Craig Bradshaw 11, Mark Dickel 10) Tour of US & Europe Players Ed Book (Nelson Giants), Craig Bradshaw (Winthrop University), Dillon Boucher (Auckland Stars), Pero Cameron (Waikato Titans), Mark Dickel (Fenerbache), Paul Henare (Hawks), Phill Jones (Nelson Giants), Sean Marks (San Antonio Spurs), Aaron Olson (Auckland Stars), Kirk Penney (Auna Gran Canaria), Brendon Polyblank (Saints), Tony Rampton (Cairns Taipans), Christopher Reay (Southern Methodist University), Paora Winitana (Hawks) Coach: Tab Baldwin Assistant Coach: Nenad Vucinic Video Coach: Murray McMahon Managers: Tony Henderson Physiotherapist: Dave Harris Results Beat Puerto -

We'll Still Work with County

+ PLUS >> FPL opens vehicle charging station, 6A PREP WRESTLING PREP SPORTS Suwannee has pair FHSAA approves 1-year place at state meet reclassification plan See Page 1B See Page 1B TUESDAY, MARCH 9, 2021 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM City: We’ll still work with county BOCC nixed ing arrangements with the project at County officials said they county feels this is in their ue to work in partnership City of Lake City last week, the North took those steps after they best interest, but it doesn’t on other projects such as joint agreements city officials indicate they Florida were under the impression close the door to working the tandem Community on utility front. still plan to work with the Mega the city would be able to with the county on this or Development Block Grants county on local projects. Industrial meet their needs for utilities any other issues,” said City for economic development, By TONY BRITT At the Board of County Park as like providing raw water Manager Joe Helfenberger where each entity plans to [email protected] Commissioners’ meeting well as put and sewer services at the during a telephone inter- apply for $1.5 million to make Thursday, the county ter- Helfenberger a stop to the NFMIP, a belief that no lon- view Monday afternoon. renovations and improve- Despite Columbia minated an interlocal agree- annexation of a county indus- ger exists. Helfenberger said the County terminating work- ment with the city on a trial park into the city limits. -

Thank You Volunteers See Pages 4 & 5 2 Friday Local Friday, April 3, 2020

FREE Established 1961 Friday ISSUE NO: 18097 SHAABAN 10, 1441 AH FRIDAY, APRIL 3, 2020 Kuwait announces 25 new As world battles virus, Olympic sports fret over lost 3 COVID-19 cases, total at 342 10 govts under fire 38 Games income amid pandemic Thank you volunteers See Pages 4 & 5 2 Friday Local Friday, April 3, 2020 The e-learning Economy today experiment growing recognition of the need for a stronger and coherent approach to health security. It called on the US administration Local Spotlight to adopt a preventive policy against epidemics, their protec- tion, and resilience. The oil sector is not the only field affected. Finance, avia- Curfew Diaries tion, retail, service and the food industry as well as many other By Muna Al-Fuzai sectors have had to cancel business, cut staff and wages, and move to emergency measures. Many countries of the world By Jamie Etheridge [email protected] have taken strict measures, including strict ban and closure on countries and capitals, which led to a complete cessation of [email protected] lobal oil prices have recorded a noticeable decline to industrial production giants. levels that haven’t been seen since 2002. The fall is due Some have however seen remarkable growth. Some stores to the collapse in demand as a result of the global pan- G and online delivery services recorded significant growth, with demic and economic shutdown. At the same time, equity mar- consumers staying home and storing goods, with continued ne of the biggest debates raging among parents of kets around the world have suffered historic losses amid warnings about the importance of household isolation and the students in private schools these days is whether intense selling linked to the coronavirus pandemic. -

2012-13 Tulsa 66Ers Media Guide Was Designed, Written and Tony Taylor

2012 • 2013 SCHEDULE NOVEMBER DECEMBER SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 TEX 7 PM 25 26 27 28 29 30 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 TEX RGV SXF RGV RGV 4 PM 7 PM 11 AM 7 PM 7 PM 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 RGV BAK BAK 4 PM 9 PM 9 PM JANUARY 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT IWA CTN 1 2 3 4 5 7 PM 7 PM 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 IDA TEX 7 PM 7 PM CTN CTN 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 30 31 6:30 PM 6:30 PM SCW 9 PM 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 FEBRUARY SCW AUS AUS 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 1 2 IWA LAD LAD ERI SCW 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 27 28 29 30 31 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ERI SPG AUS 6 PM 6 PM 7:30 PM 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 TEX TEX 3 PM 7 PM MARCH 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 SXF SXF SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 7 PM 1 2 7 PM 24 25 26 27 28 RNO SXF IWA 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 IWA 11 AM 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 IWA LAD IDA IDA APRIL 4 PM 9 PM 8 PM 8 PM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 1 2 3 4 5 6 BAK IWA SXF IWA FWN 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 7 PM 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 RGV RGV AUS AUS 31 7 PM 7 PM 7:30 PM 7 PM *ALL TIMES ARE CENTRAL AWAY HOME FOR LIVE GAME COVERAGE OF EVERY HOME AND AWAY GAME TUNE IN TO: GET YOUR TICKETS TODAY! 918.585.8444 [email protected] RADIO 1300 AM OR WATCH THE FUTURECAST LIVE STREAM AT TULSA66ERS.COM B I X B Y , O K L AHO M A PROUD AFFILIATE OF THE OKL AHOMA CIT Y THUNDER TGeneralUL InformationSA6 6StaffER SThe. -

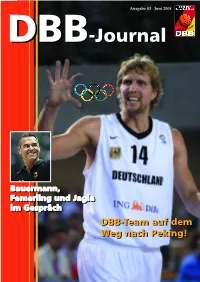

DBB-Journal DBB-Journal

Ausgabe 03 Juni 2008 DBBDBB-Journal-Journal BBaauueerrmmaannnn,, FFeemmeerrlliinngg uunndd JJaaggllaa iimm GGeesspprrääcchh DBB-TeamDBB-Team aufauf demdem WegWeg nachnach Peking!Peking! DBB-Journal 03/08 Liebe Leserinen und Leser, ich begrüße Sie zur 3. Ausgabe des DBB-Journals. Wir freuen uns, Sie heute mit einer geball- mit Perspektive“, das NBBL TOP4, die Diese Worte möchten wir Ihnen nicht vor- ten Ladung an Inhalten erfreuen zu dür- Trainer- und Schiedsrichterseiten (Neue enthalten: fen. Möglich machen es die anstehenden Regeln!!!) oder unsere Rubriken. Wir hof- Es gibt Wege im Basketball, die geht jeder. Es Herren-Länderspiele in Deutschland und fen sehr, dass Ihnen die Mischung gefällt. gib Umwege, die sind nur für Auserwählte. die anschließende Olympia-Qualifikation So ein ein Umweg ist der vdbt mit Gerhard der „Bauermänner“ in Athen. Aus diesem Eine Notiz noch am Rande: besonders Schmidt. Denn über diesen erhielt ich jetzt die Grund halten Sie nicht nur die 3. Ausgabe gefreut hat uns eine Zuschrift des ehema- Nr. 02 des DBB-Journals. Vielen Dank an des DBB-Journals, sondern gleichzeitig ligen Bundestrainers Prof. Günter Hage- beide Wege, und zugleich herzlichen Glück- auch das Hallenheft für die Spiele in Hal- dorn, der sich aus seinem „Exil“ in Korfu wunsch zu diesem faszinierenden Organ. le/Westfalen, Berlin, Bamberg, Hamburg mit gewohnt dichterischen Worten für die Nun, wer in die Sonne (aus)wanderte, wie und Mannheim in der Hand. Zusendung des DBB-Journals bedankte. ich, und andere im Regen (stehen) ließ, darf sich über Umwege nicht wundern. Denn der Natürlich räumen wir den deutschen Regen wäscht Erinnerungen ab! Herren vor diesem wichtigen, Olympi- Herzliche Grüße an alle Heutigen, Jetzigen schen Sommer den größten Platz ein. -

The Maryland Offense

20_001.qxd 31-05-2006 13:16 Pagina 1 MAY / JUNE 2006 20 FOR BASKETBALL EVERYWHERE ENTHUSIASTS FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE ASSIST Zoran Kovacic WOMEN’S U19 SERBIA AND BRENDA FRESE MONTENEGRO OFFENSE Aldo corno and mario buccoliero 1-3-1 zone trap Nancy Ethier THE MARYLAND THE IMPORTANCE OF MENTORSHIP ESTHER WENDER FIBa EUROPE’S YEAR OF WOMEN’s basketball OFFENSE Donna O’Connor THE “OPALS” STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING ;4 20_003.qxd 31-05-2006 12:03 Pagina 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2006 FIBA CALENDAR COACHES MAY FUNDAMENTALS AND YOUTH BASKETBALL 19 - 23.05 FIBA Women’s World Women’s U19 Serbia and Montenegro Offense 4 League, PR Group A, in by Zoran Kovacic Shaoxing, P.R. of China 31.05 - 08.06 FIBA Asia Champions Shooting Drills 8 Cup for Men in Kuwait by Francis Denis June OFFENSE 28.06 - 02.07 FIBA Women’s World 11 League, PR Group B, The High-Post and the Triangle Offenses in Pecs, Hungary by Geno Auriemma 28.06 - 02.07 FIBA Americas U18 The Maryland Offense 16 FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE Championship for Men by Brenda Frese IS A PUBLICATION OF FIBA in San Antonio, USA International Basketball Federation 51 – 53, Avenue Louis Casaï CH-1216 Cointrin/Geneva Switzerland 28.06 - 02.07 FIBA Americas U18 The Rational Game 20 Tel. +41-22-545.0000, Fax +41-22-545.0099 Championship for by Tamas Sterbenz www.fiba.com / e-mail: [email protected] Women in Colorado IN COLLABORATION WITH Giganti-BT&M, Cantelli Springs, USA Editore, Italy deFENSE PARTNER WABC (World Association of 1-3-1 Zone Trap 23 Basketball Coaches), Dusan Ivkovic President July 04 - 14.07 Wheelchair World by Aldo Corno e Mario Buccoliero Championship for Men, Editor-in-Chief in Amsterdam, HOOP MARKET Giorgio Gandolfi Netherlands Women's Basketball 30 18 - 27.07 FIBA Europe U18 by Raffaele Imbrogno Editorial Office: Cantelli Editore, Championship for Men V. -

Pac-10 in the Nba Draft

PAC-10 IN THE NBA DRAFT 1st Round picks only listed from 1967-78 1982 (10) (order prior to 1967 unavailable). 1st 11. Lafayette Lever (ASU), Portland All picks listed since 1979. 14. Lester Conner (OSU), Golden State Draft began in 1947. 22. Mark McNamara (CAL), Philadelphia Number in parenthesis after year is rounds of Draft. 2nd 41. Dwight Anderson (USC), Houston 3rd 52. Dan Caldwell (WASH), New York 1967 (20) 65. John Greig (ORE), Seattle 1st (none) 4th 72. Mark Eaton (UCLA), Utah 74. Mike Sanders (UCLA), Kansas City 1968 (21) 7th 151. Tony Anderson (UCLA), New Jersey 159. Maurice Williams (USC), Los Angeles 1st 11. Bill Hewitt (USC), Los Angeles 8th 180. Steve Burks (WASH), Seattle 9th 199. Ken Lyles (WASH), Denver 1969 (20) 200. Dean Sears (UCLA), Denver 1st 1. Lew Alcindor (UCLA), Milwaukee 3. Lucius Allen (UCLA), Seattle 1983 (10) 1st 4. Byron Scott (ASU), San Diego 1970 (19) 2nd 28. Rod Foster (UCLA), Phoenix 1st 14. John Vallely (UCLA), Atlanta 34. Guy Williams (WSU), Washington 16. Gary Freeman (OSU), Milwaukee 45. Paul Williams (ASU), Phoenix 3rd 48. Craig Ehlo (WSU), Houston 1971 (19) 53. Michael Holton (UCLA), Golden State 1st 2. Sidney Wicks (UCLA), Portland 57. Darren Daye (UCLA), Washington 9. Stan Love (ORE), Baltimore 60. Steve Harriel (WSU), Kansas City 11. Curtis Rowe (UCLA), Detroit 5th 109. Brad Watson (WASH), Seattle (Phil Chenier (CAL), taken by Baltimore 7th 143. Dan Evans (OSU), San Diego in 1st round of supplementary draft for 144. Jacque Hill (USC), Chicago hardship cases) 8th 177. Frank Smith (ARIZ), Portland 10th 219. -

Men Basketball.Indd

Morgan State Bears (2-6) GAME vs. Coppin State (1-4) Dec. 6, 2008, 4 p.m. EST 9 Hill Field House -- Baltimore, Md. SPORTS INFORMATION • 1700 EAST COLD SPRING LANE • BALTIMORE, MD • OFFICE (443) 885-3831 • FAX (443) 885-8307 • MORGANSTATEBEARS.COM 2008-09 Schedule Projected MSU Starters and Notes Opponent Time G 3 Jermaine “Itchy” Bolden (5-9, 175, Sr., Baltimore) 6.9 ppg, .625 FT, 4.6 apg, 1.0 spg N15 La Salle L, 61-64 Last season saw action in 30 games and started in two...averaged 5.4 ppg...2.7 apg...2.0 rpg...Shot N17 UMBC W, 67-60 33.5 percent (55-164) from the field...73.5 percent (36-49 FT) from the stripe... transferred to Morgan State N19 Manhattan L, 60-61 from South Plains Community College (Texas) N21-23 1-Glenn Wilkes Classic vs. Marshall W, 72-67 G 21 Rogers Barnes (6-1, 185, Sr., Columbia) 8.1 ppg, .404 FG, 1.9 apg, 2.1 spg vs. Utah L, 37-66 Saw action in 22 games last season...Averaged 3.9 ppg...Shot 39% (30-77) from the field...Has started in vs. Wisconsin-Green Bay L, 54-71 6-of-7 games this season...Averaging 8.1 ppg, 2.6 rpg and is shooting 37.5 percent from beyond the arc.... N29 Ole Miss L, 70-78 Averaging 28 minutes per game...Posted career-high 17 points at Ole Miss D1 St. Francis (Pa.) L, 61-65 D6 Coppin State* 4:00 p.m. D10 DePaul 7:30 p.m. -

Ties Even Bigger Than Last Year Renowned

Meet Sammy Startup, a new literary role model for aspiring Hosea Chanchez Stars in One- entrepreneurs of color Man Show ‘Good Mourning’ (See page A-2) (See page E-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 34, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, AUGUST 22, 2019 BY SAYBIN ROBERSON Contributing Writer Wednesday, August 14, Hyundai returns to this year’s festivi- 2019, Congresswoman ties even bigger than last year Maxine Waters held a hear- ing entitled, “Examining The Homelessness Crisis in Los Angeles” to discuss ending homelessness with key stakeholders in Los Angeles County. The hearing included representatives from the House Financial Services Committee, chairwoman Maxine Waters (D-CA), Rep. Al Green (D-TX), Rep. Silvia Garcia (D-TX), and Rep. Grace Napolitano (D-CA). Also welcoming members of the California Delegation including Rep. Nanette Barragan, Rep. Jimmy Gomez, Rep. Judy Zafar Brooks COURTESY PHOTO Chu, and Rep. Brad Sher- man. ROBERT TORRENCE/L.A. SENTINEL BY LAUREN FLOYD for Hyundai Motor Ameri- Held at the California (L-R) Rep. Sylvia Garcia, Rep. Maxine Waters and Rep. Al Green Staff Writer ca, Zafar Brooks, says that African American Muse- working and connecting di- um, the hearing focused on House Financial Services homelessness crisis in Los Mayor, Peter Lynn, Execu- It’s been four years rectly with the community current and future plans to Committee, I have made it Angeles, and the federal, tive Director, Los Angeles since Hyundai first becameduring events like Taste of decrease the large amount a top priority to focus on state, and local responses to Homeless Services Author- a sponsor for Bakewell Soul creates a large impact. -

6 October 2016 Dear Candidate, As Americans Across the Country

6 October 2016 Dear Candidate, As Americans across the country prepare to elect a new President and Congress, the Copyright Alliance and CreativeFuture – two organizations that strongly support creative communities by working to protect creativity and encourage respect for copyright law – have partnered on letters (attached here) and a Change.org petition, to ensure that the views of the creative communities are heard. Signed by over 35,000 creatives, audience members, fans, and consumers, the letters recognize that the internet is a powerful and democratizing force, but also stress the need for a strong copyright system that rewards creativity and promotes a healthy creative economy. Whether you are a Democrat or Republican, liberal or conservative or libertarian, strong and effective copyright is not a partisan issue, but rather one that benefits our entire country. The letters and petition discuss the complementary relationship between a strong copyright system, free expression, creativity, innovation, and technology. The signers affirmed: • We embrace the internet as a powerful democratizing force for creative industries and the world at large. • We embrace a strong copyright system that rewards creativity and promotes a healthy creative economy. • We proudly assert that copyright promotes and protects free speech. • Copyright should allow creative communities to safeguard their rights against those who would use the internet to undermine creativity. • Creative communities must be part of the conversation and stand up for creativity. Sincerely, Ruth Vitale Keith Kupferschmid CEO, CreativeFuture CEO, Copyright Alliance Open Letter to 2016 Political Candidates We are members of the creative community. While our political views are diverse, as creatives, there are core principles on which we can all agree. -

When Is a Basket Not a Basket? the Basket Either Was Made Before the Clock Expired Or Nswer: When 3 the Protest by After

“Local name, national Perspective” $3.95 © Volume 4 Issue 6 NBA PLAYOFFS SPECIAL April 1998 BASKETBALL FOR THOUGHT by Kris Gardner, e-mail: [email protected] A clock was involved; not a foul or a violation of the rules. When is a Basket not a Basket? The basket either was made before the clock expired or nswer: when 3 The protest by after. The clock provides tan- officials and deter- the losing gible proof. This wasn’t a commissioner mina- team. "The charge or block call. Period. David Stern tion as Board of No gray area here. say so. to Governors Secondly, it’s time the Sunday, April 12, the whethe has not league allows officials to use Knicks apparently defeated r a ball seen fit to replay when dealing with is- the Miami Heat 83 - 82, on a is shot adopt such sues involving the clock. It’s last second rebound by G prior a rule," the sad that the entire viewing Allan Houston. Replays to the Commis- audience could see replays showed Allan scored the bas- expira- sioner showing the basket should be ket with 2 tenths of a second tion of stated, allowed and not the 3 most on the clock. However, offi- time, "although important people—the refer- cials disagreed. They hud- Stern © ees calling the game! Ironi- dled after the shot for 30 "...although the subject has been considered from time to cally, the officials viewed the seconds to determine if they time. Until it does so, such is not the function of the replays in the locker after the were all in agreement. -

2008 FB MG.Qxp

President’s Welcome Western has a long tradition of excel- and reinforce a strong work ethic, accountability, lence in athletics. It is a tradition made possible and the importance of community. At Western by talented and dedicated coaches, by student- our coaches and athletes represent the very athletes who are committed to excellence and best of what college athletics, in its essence, by loyal supporters who believe in the important provides. As supporters of Western State benefits of intercollegiate athletics. College athletics you help make it all possible. At Western we are proud of the fact that On behalf of the coaches, athletic staff, "we make champions out of thin air." Last year and the student-athletes I thank you for your there were many outstanding performances by commitment to Western and for your support of Western student-athletes and teams. As a intercollegiate athletics. whole, Western State has been ranked in the Top 25 of the Division II National Directors’ Cup Contest each of the 13 years of the contest. While we are proud of the accomplishments and efforts of our athletes, teams and coaches, we also believe that the development of cham- pions reaches far wider and deeper than con- tests won and lost. In addition to being highly competitive NCAA II participants and successful students, Western's student-athletes are involved in many other campus activities. Their participation Jay Helman includes activities such as residence life staff, WSC President student government, theatre and new student orientation. Clearly, student-athletes at Western are an integral part of campus life and represent the values of citizenship and community that our college so strongly supports and encourages.