The Bhagavad Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversations with Swami Turiyananda

CONVERSATIONS WITH SWAMI TURIYANANDA Recorded by Swami Raghavananda and translated by Swami Prabhavananda (This month's reading is from the Jan.-Feb., 1957 issue of Vedanta and the West.) The spiritual talks published below took place at Almora in the Himalayas during the summer of 1915 in the ashrama which Swami Turiyananda had established in cooperation with his brother-disciple, Swami Shivananda. During the course of these conversations, Swami Turiyananda describes the early days at Dakshineswar with his master, Sri Ramakrishna, leaving a fascinating record of the training of an illumined soul by this God-man of India. His memories of life with his brother-disciples at Baranagore, under Swami Vivekananda’s leadership, give a glimpse of the disciplines and struggles that formed the basis of the young Ramakrishna Order. Above all, Swami Turiyananada’s teachings in the pages that follow contain practical counsel on many aspects of religious life of interest to every spiritual seeker. Swami Turiyananda spent most of his life in austere spiritual practices. In 1899, he came to the United States where he taught Vedanta for three years, first in New York, later on the West Coast. By the example of his spirituality he greatly influenced the lives of many spiritual aspirants both in America and India. He was regarded by Sri Ramakrishna as the perfect embodiment of that renunciation which is taught in the Bhagavad Gita Swami Shivananda, some of whose talks are included below, was also a man of the highest spiritual realizations. He later became the second President of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. -

Sri Ramakrishna, Modern Spirit, and Religion

SWAMI PRABHAVANANDA RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY Sri Ramakrishna, Modern Spirit, and Religion SWAMI PRABHAVANANDA mongst the students of religion who men alive. Yet the state of samàdhi still are acquainted with the life of Sri remained to him an abnormality. ARamakrishna, perhaps only a few In this connection one may also mention regard his life in all its phases as historically Professor Max Muller, and Romain Rolland, true. To these few, what appears to the rest biographers of Ramakrishna, and two of the as belonging to the class of legend and greatest thinkers of our age. They were mythology becomes living spiritual truth. To attracted to and admired the superior spiritual them even the lives of Krishna, Buddha, or genius of the man Ramakrishna, yet viewed Christ which seem lost in the mist of myth many of the incidents of his life as legendary, and legend become true and living in the and some of his spiritual experiences as light of the life of Ramakrishna. But apart delusions, or mental aberrations. from these few, however, to most people Let us, therefore, analyse why there is who have drunk deep of the modern spirit, this contradiction in the estimation of who refuse to accept anything as true which Ramakrishna; why he is accepted as a is beyond the realm of their personal spiritual genius by those very people who at discoveries and thus are circumscribed by the same time reject some of the most their own limitations, much that is told of Sri important experiences of his life— Ramakrishna’s life appears as legendary, experiences which made him what he was. -

THE SERMON on the MOUNT According to VEDANTA Other MENTOR Titles of Related Interest

\" < 'y \ A MENTOR BOOK 1 ,wami \ « r a m A |a fascinating Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Public.Resource.Org https://archive.org/details/sermononmountaccOOprab 66Like Krishna and Buddha, Christ did not preach a mere ethical or social gos¬ pel hut an uncompromisingly spiritual one. He declared that God can be seen, that divine perfection can be achieved. In order that men might attain this su¬ preme goal of existence, he taught the renunciation of worldliness, the con¬ templation of God, and the purification of the heart through the love of God. These simple and profound truths, stated repeatedly in the Sermon on the Mount, constitute its underlying theme9 as I shall try to show in the pages to followr —from the Introduction by Swami Prabhavananda THE SERMON ON THE MOUNT according to VEDANTA Other MENTOR Titles of Related Interest □ SHAN KARA'S CREST-JEWEL OF DISCRIMINA¬ TION translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Ssherwood. The philosophy of the great Indian philosopher and saint, Shankara. Its implications for the man of today are sought out in the Introduction, (#MY1054—$1.25) □ THE SONG OF GOD: RHAGAVAD-GITA translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isher- wood. A distinguished translation of the Gospel of Hinduism, one of the great religious classics of the world. Introduction by Aldous Huxley. Appen¬ dices. (#MY1425—$1.25) □ THE UPAN5SHAD8: BREATH OF THE ETERNAL translated by Swam! Prabhavananda and Freder¬ ick Manchester. Here is the wisdom of the Hindu mystics in principal texts selected and translated from the original Sanskrit. (#MY1424—$1.25) □ HOW TO KNOW GOD: THE YOGA APHORISMS OF PATANJALI translated with Commentary by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isher- wood. -

The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali

The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjai TRANSLATED WITH A NEW COMMENTARY BY SWAMI PRABirtA ANDA AND CHRISTOPHER 0 . SI AMAKISA MA 1 SI AMAKISA MA OA MYAOE MAAS - IIA PUBLISHED BY © THE PRESIDENT SRI RAMAKRISHNA MATH MADRAS-600 004 FIRST PUBLISHED , BY VEDANTA SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2-MC 2 82 PRINTED IN INDIA PHOTOCOMPOSED AT AUROPHOTOSE'TTERS, PONDICHERRY rntd t O O OSE ESS, Mdr2 UISES O E It th rt plr tht prnt t r rdr th Indn Edtn f t n Gd b S rbhvnnd. h Enlh trnltn f tnjl Y Str rnll pblhd b th dnt St, Sthrn Clfrn fr th bnft f Wtrn rdr h d nt n Snrt nd t r ntrtd n Indn phl hh plb th dpth f th hn nd. S rbhvnnd h h t h rdt h ld xptn `Srd hvd Gt, th d f Gd, `rd f vn v nd th Srn n th Mnt rdn t dnt h tn pl pn n th b t prnt th phlph nd prt f Y n nnthnl, ptdt phrl tht n b ndrtd nd njd b ll nrn nd. r th bnft f r Indn rdr hv ddd l th txt f tnjl Str n vnr. W r r tht th ll fnd th b nntl hlpfl n thr ptl prt. W r thnfl t S rbhv nndj nd th dnt St, Sthrn Clfrn fr nd prn t brn t th Indn dtn. Sr rhn Mth UISE Mdr600 004. CONTENTS Translators' Foreword The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanfali I YOGA A IS AIMS 1 II YOGA A IS ACICE 57 I OWES 112 Iv. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Vedanta and Chritianity

Vedanta and Chritianity By Swami Tathagatananda A new wind is blowing all over the world due to the influence of Vedanta, and some Christian writers are voicing their views in this regard. Wisdom in Vedanta demonstrates a harmonious attitude of acceptance of all other religions. Hinduism has never prevented Christians and believers of other faiths from practicing their own spiritual traditions within India, which has been home to all the major world religions. It is known to all that in spite of the high philosophy of Hinduism, Hindus could not live up to its precepts; hence, Hindu society suffered gravely in many ways. Swami Vivekananda did not hesitate to point out, “No religion on earth preaches the dignity of humanity in such a lofty strain as Hinduism, and no religion on earth treads upon the necks of the poor and the low in such a fashion as Hinduism” (C. W., V: 15). Hinduism is not to blame; people in general under any culture, are not able to follow the precepts of their culture. Swamiji says, “Renunciation and spirituality are the two great ideas of India, and it is because India clings to these ideas that all her mistakes count for so little” (C. W., II: 372). In fact, the current inter-denominational approach of Christianity actually has its roots in Vedanta’s dynamic philosophy of spiritual unity. Christians have been safely practicing their faith in India since the first century A. D., with the visit of Christ’s disciple St. Thomas to Kerala. Although the Christian presence has been penetrating India first by imperialist and colonialist force in the sixteenth century and later by the force of ideas, four centuries later we see that India’s tolerance and accommodative spirit helped Christianity to thrive in India without fear and without interference. -

K.P. Aleaz, "The Gospel in the Advaitic Culture of India: the Case of Neo

The Gospel in the Advaitic Culture of India : The Case ofNeo-Vedantic Christologies K.P.ALEAZ * Advaita Vedanta is a religiqus experience which has taken birth in the soil of our motherland. One important feature of this culmination of Vedic thought (Vedanta) is that it cannot be tied down to the narrow boundaries of any one particular religion. Advaita Vedanta stands for unity and universality in the midst of diversities.1 As a result it can very well function as a symbol of Indian composite culture. Advaita has "an enduring influence on the clutural life of India enabling people to hold together diversities in languages, races, ethnic groups, religions, and more recently different political ideologies as well. " 2 It was its cultural unity based on religion that held India together historically as one. The survival of the political unity of India is based on its cultural · unity within which there persists a 'core' of religion to which the senseofAdvaitaor'not-twoism'makesanenduringcontribution.3 Advaita represents a grand vision of unity that encompasses nature, humanity and God.4 Sociological and social anthropological studies have shown that in Indian religious tradition the sacred is not external to the secular; it is the inherent potency ofthe secualr. There is a secular-sacred continuum. There is a continuum between the gods and the humans, a continuum of advaita, and this is to be found even among the primitive substratum of Indian population. 5 So the point is, such a unitive vision of Advaita is very relevant for an Indian understanding of the gospel manifested in Jesus. -

Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi

american vedantist Volume 15 No. 3 • Fall 2009 Sri Sarada Devi’s house at Jayrambati (West Bengal, India), where she lived for most of her life/Alan Perry photo (2002) Used by permission Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi Vivekananda on The First Manifestation — Page 3 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE A NOTE TO OUR READERS American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is dedicated to developing VedantaVedanta in the West,West, es- American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is a not-for-profinot-for-profi t, quarterly journal staffedstaffed solely by pecially in the United States, and to making The Perennial Philosophy available volunteers. Vedanta West Communications Inc. publishes AV four times a year. to people who are not able to reach a Vedanta center. We are also dedicated We welcome from our readers personal essays, articles and poems related to to developing a closer community among Vedantists. spiritual life and the furtherance of Vedanta. All articles submitted must be typed We are committed to: and double-spaced. If quotations are given, be prepared to furnish sources. It • Stimulating inner growth through shared devotion to the ideals and practice is helpful to us if you accompany your typed material by a CD or fl oppy disk, of Vedanta with your text fi le in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Manuscripts also may • Encouraging critical discussion among Vedantists about how inner and outer be submitted by email to [email protected], as attached fi les (preferred) growth can be achieved or as part of the e mail message. • Exploring new ways in which Vedanta can be expressed in a Western Single copy price: $5, which includes U.S. -

VII. the Swami Swahananda Era (1976-2012)

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present VII. The Swami Swahananda Era (1976-2012) 1. Swami Swahananda’s Background 2. Swami Swahananda’s Major Objectives 3. Swami Swahananda at the Vedanta Society of Southern California 4. The Assistant Swamis 5. Functional Departments of the Vedanta Society 6. Charitable Organizations 7. Santa Barbara Temple and Convent 8. Ramakrishna Monastery, Trabuco Canyon 9. Vivekananda House, South Pasadena (1955-2012) 1. Swami Swahananda’s Background* fter Swami Prabhavananda passed away on July 4, 1976, Swami Chetanananda was assigned the position of head of the A Vedanta Society of Southern California (VSSC). Swamis Vireswarananda and Bhuteshananda, President and Vice- President of the Ramakrishna Order, urged Swami Swahananda to take over the VSSC. They realized that a man with his talents and capabilities should be in charge of a large center. Swahananda agreed to leave the quiet life of Berkeley for the more challenging work in the Southland. Having previously been in charge of the large New Delhi Center in the capital of India, he was up to the task and assumed leadership of the VSSC on December 15, 1976. He was enthusiastically welcomed, and soon became well established in the life of the Society. Swami Swahananda was born on June 29, 1921 in Habiganj, Sylhet in Bengal (now in Bangladesh). His father had been a government official and an initiated disciple of Holy Mother. He had wanted to renounce the world and become a monk, but Holy Mother reportedly had told him, “No, my child, but from your family two shall come.” (As well as Swahananda, a nephew also later joined the Ramakrishna Order). -

Life of Swami Brahmananda (Raja Maharaj)

Direct Disciples of Sri Ramakrishna Life of Swami Brahmananda (Raja Maharaj) (1863-1922) "Mother, once I asked Thee to give me a companion just like myself. Is that why Thou hast given me Rakhal?" -- Sri Ramakrishna (conversing with the Divine Mother) "Ah, what a nice character Rakhal has developed! Look at his face and every now and then you will notice his lips moving. Inwardly he repeats the name of God, and so his lips move. "Youngsters like him belong to the class of the ever-perfect. They are born with God- Consciousness. No sooner do they grow a little older than they realize the danger of coming in contact with the world. There is the parable of the homa bird in the Vedas. The bird lives high up in the sky and never descends to earth. It lays its eggs in the sky, and the egg begins to fall. But the bird lives in such a high region that the egg hatches while falling. The fledgling comes out and continues to fall. But it is still so high that while falling it grows wings and its eyes open. Then the young bird perceives that it is dashing down toward the earth and will be instantly killed. The moment it sees the ground, it turns and shoots up toward its mother in the sky. Then its one goal is to reach its mother. "Youngsters like Rakhal are like that bird. From their very childhood they are afraid of the world, and their one thought is how to reach the Mother, how to realize God." -- Sri Ramakrishna Swami Brahmananda (1863-1922), whose life and teachings are recorded in this, was in a mystical sense, an 'eternal companion' of the Great Master, Sri Ramakrishna. -

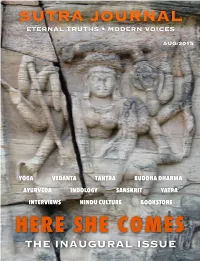

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization. -

Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow

The Matheson Trust Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow Published in Asian Philosophy (Nottingham) 2:2, 1992 Abstract Like all monisms Vedanta posits a distinction between the relatively and the absolutely Real, and a theory of illusion to explain their paradoxical relationship. Sankara's resolution of the problem emerges from his discourse on the nature of maya which mediates the relationship of the world of empirical, manifold phenomena and the one Reality of Brahman. Their apparent separation is an illusory fissure deriving from ignorance and maintained by 'superimposition'. Maya, enigmatic from the relative viewpoint, is not inexplicable but only not self-explanatory. Sankara's exposition is in harmony with sapiential doctrines from other religious traditions and implies a profound spiritual therapy. * Maya is most strange. Her nature is inexplicable. (Sankara)i Brahman is real; the world is an illusory appearance; the so-called soul is Brahman itself, and no other. (Sankara)ii I The doctrine of maya occupies a pivotal position in Sankara's metaphysics. Before focusing on this doctrine it will perhaps be helpful to make clear Sankara's purposes in elaborating the Advaita Vedanta. Some of the misconceptions which have afflicted English commentaries on Sankara will thus be banished before they can cause any further mischief. Firstly, Sankara should not be understood or approached as a 'philosopher' in the modern Western sense. Ananda Coomaraswamy has rightly insisted that, The Vedanta is not a philosophy in the current sense of the word, but only as it is used in the phrase Philosophia Perennis... Modern philosophies are closed systems, employing the method of dialectics, and taking for granted that opposites are mutually exclusive.