The Hawaii Nisei Story: Creating a Living Digital Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Hawaiian and Japanese American Discourse Over Hawaiian Statehood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Kevin and Tam Ross Undergraduate Research Prize Leatherby Libraries Spring 2021 3rd Place Contest Entry: Sovereignty, Statehood, and Subjugation: Native Hawaiian and Japanese American Discourse over Hawaiian Statehood Nicole Saito Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/undergraduateresearchprize Part of the American Politics Commons, American Studies Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Hawaiian Studies Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Political History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Saito, Nicole, "3rd Place Contest Entry: Sovereignty, Statehood, and Subjugation: Native Hawaiian and Japanese American Discourse over Hawaiian Statehood" (2021). Kevin and Tam Ross Undergraduate Research Prize. 30. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/undergraduateresearchprize/30 This Contest Entry is brought to you for free and open access by the Leatherby Libraries at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kevin and Tam Ross Undergraduate Research Prize by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Research and Library Resources Essay My thesis was inspired by the article “Why Asian Settler Colonialism Matters” by sociologist Dean Saranillio, which chronicles Asian Americans’ marginalization of Native Hawaiians. As an Asian American from Hawaii, I was intrigued by this topic. My project thus investigates the consequences Japanese American advocacy for Hawaiian statehood had on Native Hawaiians. Based on the Leatherby Library databases that Rand Boyd recommended, I started my research by identifying key literature through Academic Search Premier and JSTOR. -

A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Other History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Caleb Kenji, "Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 206. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/206 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Caleb Kenji Watanabe Arkansas Tech University Bachelor of Arts in History, 2009 December 2011 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Comparing the Japanese American relocation centers of Arkansas and the camp systems of Hawaii shows that internment was not universally detrimental to those held within its confines. Internment in Hawaii was far more severe than it was in Arkansas. This claim is supported by both primary sources, derived mainly from oral interviews, and secondary sources made up of scholarly research that has been conducted on the topic since the events of Japanese American internment occurred. -

Welcome to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Community 2 0 Asiantation Table of Contents

2 0 Asiantation Welcome to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Community 2 0 Asiantation Table of Contents 1 "Asiantation Not Orientation" 2 Welcome to Asiantation 3 About Asiantation 4 AACC-Affiliated Registered Student Organizations 16 Other Registered Student Organizations AACC 17 17 | About the AACC 18 | Programs & Services 20 | International Education 21 | Facility 22 Asian American Studies 23 Academic Departments 24 Arts & Entertainment 25 Campus Resources 28 Student Publications 28 | "Unlearn" 29 | "Asian American Awareness" 30 | "Mental Health" 31 | "Date a Filipino" 32 | "Voting: Why?" "Asiantation Not Orientation" Why is it called Asiantation instead of Orientation? The title did not come out of nowhere - this poem describes it best. ASIAN ORIENTAL is not is a fad: yin-yang, kung fu Oriental. "say one of them funny words for me" Head bowed, submissive, industrious Oriental is downcast eyes, china doll hard working, studious "they all look alike" quiet Oriental is sneaky Oriental is a white man's word. ASIAN is not being Oriental, WE Lotus blossom, exotic passion flower are not Oriental. inscrutable we have heard the word all our lives we have learned to be Oriental ASIAN we have learned to live it, speak it, is not talking play the role, Oriental. and to survive in a white world ahh so, ching chong chinaman become the role. no tickee, no washee The time has come to look at who gave the name ORIENTAL is a white man's word. Anonymous Oriental is jap, flip, chink, gook it's "how 'bout a backrub mama-san" it's "you people could teach them niggers and mexicans a thing or two you're good people none of that hollerin' and protesting" This poem has appeared in every Asiantation Resource Booklet since its origination. -

Fall October 2016

Asian Pacific American Community Newspaper Serving Sacramento and Yolo Counties - Volume 29, No. 3 Fall/October 2016 Register & Vote API vote sought by INSIDE CURRENTS ACC Senior Services - 3 Will you be 18 years old and a US major parties Iu-Mien Commty Svc - 5 citizen by November 4th? YES?? YOU While much attention is focused on GET TO VOTE!! But you need to register Hispanic and black voters, Asian Pacific Islander Chinese Am Council of Sac-7 to vote by Monday October 24th. are the single fastest growing demographic group and that has drawn the attention of You can register to vote online at major political parties. In states like Nevada sos.ca.gov (Secretary of State website), and Virginia, where polls show that the ask your local county elections office to presidential race is down to single digits, the Sacramento APIs send you a voter registration form or go API vote can swing the outcome of national and local elections. API voters are 8.5 - 9% of targeted by robbers in person to your local elections office. the voters in Nevada, 5 - 6.5% in Virginia, 7% Voter registration forms online are in New Jersey, 3.1% in Minnesota, and 15% in The Sacramento police announced available in 12 languages. California. In a tight race, the API vote can make that about 20 people have been arrested for a difference. Nine million APIs will be eligible to armed robberies targeting API residents. The vote in November, up 16% from four years ago. police say that the suspects do not appear to Nationally, API voters are about 4%. -

A Participatory Study of the Self-Identity of Kibei Nisei Men: a Sub Group of Second Generation Japanese American Men William T

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 1993 A Participatory Study of the Self-Identity of Kibei Nisei Men: A Sub Group of Second Generation Japanese American Men William T. Masuda University of San Francisco Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Asian History Commons, Migration Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Masuda, William T., "A Participatory Study of the Self-Identity of Kibei Nisei Men: A Sub Group of Second Generation Japanese American Men" (1993). Doctoral Dissertations. 472. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/472 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The author of this thesis has agreed to make available to the University community and the public a copy of this thesis project. Unauthorized reproduction of any portion of this thesis is prohibited. The quality of this reproduction is contingent upon the quality of the original copy submitted. University of San Francisco Gleeson Library/Geschke Center 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117-1080 USA The University of San Francisco A PARTICIPATORY STUDY OF THE SELF-IDENTITY OF KIBEI NISEI MEN: A SUB GROUP OF SECOND GENERATION JAPANESE AMERICAN MEN A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty ofthe School ofEducation Counseling and Educational Psychology Program In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education by William T. -

Matson Foundation 2014 Manifest

MATSON FOUNDATION 2014 MANIFEST THE 2014 REPORT OF THE CHARITABLE SUPPORT AND COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES OF MATSON, INC. AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES IN HAWAII, THE PACIFIC, AND ON THE U.S. MAINLAND. MESSAGE FROM THE CEO One of Matson’s core values is to contribute positively to Matson Foundation 2014 Leadership the communities in which we work and live. It is a value our employees have generously demonstrated throughout Pacific Committee our long, rich history, and one characterized by community Chair, Gary Nakamatsu, Vice President, Hawaii Sales service and outreach. Whether in Hilo, Hawaii or Oakland, Vic Angoco Jr., Senior Vice President, Pacific California or Savannah, Georgia, our employees have guided Russell Chin, District Manager, Hawaii Island Jocelyn Chagami, Manager, Industrial Engineering our corporate giving efforts to a diverse range of causes. Matt Cox, President & Chief Executive Officer While we were able to show our support in 2014 for 646 Len Isotoff, Director, Pacific Region Sales organizations that reflect the broad geographic presence of Ku’uhaku Park, Vice President, Government & Community Relations our employees, being a Hawaii-based corporation which has Bernadette Valencia, General Manager, Guam and Micronesia served the Islands for over 130 years, most of our giving was Staff: Linda Howe, [email protected] - directed to this state. In total, we contributed $1.8 million Ka Ipu ‘Aina Program Staff: Keahi Birch in cash and $140,000 of in-kind support. This includes two Adahi I ‘Tano Program Staff (Guam): Gloria Perez special environmental partnership programs in Hawaii and Guam, Ka Ipu ‘A- ina and Adahi I Tano’, respectively. Since its Mainland Committee inception in 2001, Ka Ipu ‘A- ina has generated over 1,000 Chair, David Hoppes, Senior Vice President, Ocean Services environmental clean-up projects in Hawaii and contributed Patrick Ono, Sales Manager, Pacific Northwest* Gregory Chu, Manager, Freight Operations, Pacific Northwest** over $1 million to Hawaii’s charities. -

2015 3Rd Quarter

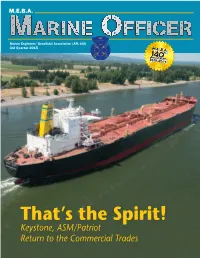

M.E.B.A. Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (AFL-CIO) 3rd Quarter 2015 That’s the Spirit! Keystone, ASM/Patriot Return to the Commercial Trades Faces around the Fleet Another day on the MAERSK ATLANTA, cutting out a fuel pump in the Red Sea. From left to right are 1st A/E Bob Walker, C/E Mike Ryan, 3rd A/E Clay Fulk and 2nd A/E Gary Triguerio. C/E Tim Burchfield had just enough time to smile for shutterbug Erin Bertram (Houston Branch Agent) before getting back to overseeing important operations onboard the MAERSK DENVER. The vessel is a Former Alaska Marine Highway System engineer and dispatcher Gene containership managed by Maersk Line, Ltd that is Christian took this great shot of the M/V KENNICOTT at Vigor Industrial's enrolled in the Maritime Security Program. Ketchikan, Alaska yard. The EL FARO sinking (ex-NORTHERN LIGHTS, ex-SS PUERTO RICO) was breaking news as this issue went to press. M.E.B.A. members past and present share the grief of this tragedy with our fellow mariners and their families at the AMO and SIU. On the Cover: M.E.B.A. contracted companies Keystone Shipping and ASM/Patriot recently made their returns into the commercial trades after years of exclusively managing Government ships. Keystone took over operation of the SEAKAY SPIRIT and ASM/Patriot is managing the molasses/sugar transport vessel MOKU PAHU. Marine Officer The Marine Officer (ISSN No. 10759069) is Periodicals Postage Paid at The Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (M.E.B.A.) published quarterly by District No. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05v6t6rn Author Kameyama, Eri Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian American Studies By Eri Kameyama 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations By Eri Kameyama Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Chair ABSTRACT: The recent census shows that one-third of those who identified as Japanese-American in California were foreign-born, signaling a new-wave of immigration from Japan that is changing the composition of contemporary Japanese-America. However, there is little or no academic research in English that addresses this new immigrant population, known as Shin-Issei. This paper investigates how Shin-Issei who live their lives in a complex space between the two nation-states of Japan and the U.S. negotiate their ethnic identity by looking at how these newcomers find a sense of belonging in Southern California in racial, social, and legal terms. Through an ethnographic approach of in-depth interviews and participant observation with six individuals, this case-study expands the available literature on transnationalism by exploring how Shin-Issei negotiations of identities rely on a transnational understandings of national ideologies of belonging which is a less direct form of transnationalism and is a more psychological, symbolic, and emotional reconciliation of self, encompassed between two worlds. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 San Francisco, California * Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, CA, 1893-1953. M1410. 429 rolls. Boll Contents 1 May 1, 1893, CITY OF PUBLA-February 7, 1896, GAELIC 2 March 4, 1896, AUSTRALIA-October 2, 1898, SAN BLAS 3 October 26, 1898, ACAPULAN-October 1, 1899, INVERCAULA 4 November 1, 1899, CITY OF PUBLA-October 31, 1900, CURACAO 5 October 31, 1900, CURACAO-December 23, 1901, CITY OF PUEBLO 6 December 23, 1901, CITY OF PUEBLO-December 8, 1902, SIERRA 7 December 11, 1902, ACAPULCO-June 8, 1903, KOREA 8 June 8, 1903, KOREA-October 26, 1903, RAMSES 9 October 28, 1903, PERU-November 25, 1903, HONG KONG MARU 10 November 25, 1903, HONG KONG MARU-April 25, 1904, SONOMA 11 May 2, 1904, MELANOPE-August 31, 1904, ACAPULCO 12 August 3, 1904, LINDFIELD-December 17, 1904, MONGOLIA 13 December 17, 1904, MONGOLIA-May 24, 1905, MONGOLIA 14 May 25, 1905, CITY OF PANAMA-October 23, 1905, SIBERIA 15 October 23, 1905, SIBERIA-January 31, 1906, CHINA 16 January 31, 1906, CHINA-May 5, 1906, SAN JUAN 17 May 7, 1906, DORIC-September 2, 1906, ACAPULCO 18 September 2, 1906, ACAPULCO-November 8, 1906, KOREA Roll Contents Roll Contents 19 November 8, 1906, KOREA-Feburay 26, 1907, 56 April 11, 1912, TENYO MARU-May 28, 1912, CITY MONGOLIA OF SYDNEY 20 March 3, 1907, CURACAO-June 7, 1907, COPTIC 57 May 28, 1912, CITY OF SYDNEY-July 11, 1912, 21 May 11, 1907, COPTIC-August 31, 1907, SONOMA MANUKA 22 September 1, 1907, MELVILLE DOLLAR-October 58 July 11, 1912, MANUKA-August -

Senator Spark M. Matsunaga Papers

Senator Spark M. Matsunaga Papers Finding Aid Hawaii Congressional Papers Collection Archives & Manuscripts Department University of Hawaii at Manoa Library January 2005 Table of Contents Introductory Information ……………………………………………………………….. 1 Administrative Information …………………..………………………………………… 2 Biographical Sketch …………………..………………………………………………….. 3 Biographical Chronology ………………………………………………………………... 4 Scope & Content Note …………..……………..………………………….……………… 8 Series Descriptions …….…………..………..…………………….……………………… 10 Series, Subseries & Sub-subseries Listing …………………………………………..… 14 Inventory …………………………..…………..……………………….……… Upon request Introductory Information Collection Name: Senator Spark M. Matsunaga Papers Accession Number: HCPC 1997.01 Inclusive Dates: 1916-1990 (bulk 1963-1990) Size of Collection: 908 linear feet Creator of Papers: Spark Masayuki Matsunaga Abstract: Spark Matsunaga (1916-1990) was a member of Congress from Hawaii, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives (1963-1976) and the U.S. Senate (1977-1990). He started his political career as an assistant public prosecutor in Honolulu (1952-1954), was a Representative in the Territory of Hawaii Legislature (1954-1959), worked tirelessly for Hawaii statehood, and was also a lawyer in private practice. He served in the U.S. Army, in the famed 100 th Infantry Battalion during WWII, receiving the Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts. He married Helene Hatsumi Tokunaga in 1948 and had five children. The bulk of the collection is from Matsunaga’s years in Congress and includes correspondence, photographs, audiovisual items, and memorabilia. The largest parts of this material concern Congressional activity supporting his strong interest in peace, space exploration, veterans, transportation, taxation, health, natural resources and civil rights, especially redress for Japanese Americans interned in WWII. His legendary hosting of constituents in Congressional dining rooms is shown in many invoices and guest lists. His staff kept detailed information on his schedules, appointments and travels. -

1962 November Engineers News

OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCI( 3 ~63T o ' .. Vol. 21 - No. 11 SANFRA~CISCO, ~AliFORN!~ . ~151 November1 1962 LE ·.·. Know Your . Friends greem~l1t on _And Your Enemies On.T o Trusts ;rwo ·trust instruni.ents for union-management' joint ad· ministration of Novel;llber 6 is Election Pay-,-a day that is fringe benefits negotiated by Operating En. gineers to e very American of voting age, but particularly Local 3 in the last industry agreement were· agreed upon in October. ' · ._. to men:tbers of Ope•rating Engineers Local 3. · The • -/ trust in~truments wen~ for the Operating Engineers · Voting~takirig a perso~al hand in the selection of the · Apprentice & J o urn e y m an ' · . men who w_ill ·make our laws an:d administer them on the . Training Fund and -for Health trust documents, Local 3 Bus. val~ ious levels of gov~minent-is a privilege· our~· aricestors· & Welfare benefits for pensioned Mgr. Al Clem commented: "The - -· fought: for. and thaC we . ~hould trel(lsure. But for most of Engineers. Negotiating Committee's discus- ·the . electorate. it's · simply that, a free man's privilege; not . · Agreement on the two trusts sions with the employers were an obligati_on. · . · . came well in advance_of January cordial and cooperative. We are - For members o{ Local 3, P,owev~r, _ lt's some•thing more 1, WB3, de~dlines which provided gratified that our members will ) han that; it comes cl(!?~r· t.9 b~, ing .<rb!ndiilg obligation. - that if union and employer .nego- be able to ·get the penefit of .· _If you'r~-::~dtpi- 1se f~y ti1i{ 'statement;· it might be in tiators couldn't acrree on either these trusts without delay and or der .::to"'ask:. -

AACP BOARD of DIRECTORS Florence M. Hongo, President Kathy Reyes, Vice President Rosie Shimonishi, Secretary Don Sekimura, Treasurer Leonard D

AACP BOARD OF DIRECTORS Florence M. Hongo, President Kathy Reyes, Vice President Rosie Shimonishi, Secretary Don Sekimura, Treasurer Leonard D. Chan Sutapa Dah Joe Chung Fong, PhD. Michele M. Kageura Susan Tanioka Sylvia Yeh Shizue Yoshina HONORARY BOARD Jerry Hiura Miyo Kirita Sadao Kinoshita Astor Mizuhara, In Memoriam Shirley Shimada Stella Takahashi Edison Uno, In Memoriam Hisako Yamauchi AACP OFFICE STAFF Florence M. Hongo, General Manager Mas Hongo, Business Manager Leonard D. Chan, Internet Consultant AACP VOLUNTEERS Beverly A. Ang, San Jose Philip Chin, Daly City Kiyo Kaneko, Sunnyvale Michael W. Kawamoto, San Jose Peter Tanioka, Merced Paul Yoshiwara, San Mateo Jaime Young AACP WELCOMES YOUR VOLUNTEER EFFORTS AACP has been in non-profit service for over 32 years. If you are interested in becoming an AACP volunteer, call us at (650) 357-1008 or (800) 874-2242. OUR MISSION To educate the public about the Asian American experience, fostering cultural awareness and to educate Asian Americans about their own heritage, instilling a sense of pride. CREDITS Typesetting and Layout – Sue Yoshiwara Editor– Florence M. Hongo/ Sylvia Yeh Cover – F.M. Hongo/L. D. Chan TABLE OF CONTENTS GREETINGS TO OUR SUPPORTERS i ELEMENTARY (Preschool through Grade 4) Literature 1-6 Folktales 7-11 Bilingual 12-14 ACTIVITIES (All ages) 15-19 Custom T-shirts 19 INTERMEDIATE (Grades 5 through 8) Educational Materials 20-21 Literature 22-26 Anti-Nuclear 25-26 LITERATURE (High School and Adult) Anthologies 27-28 Cambodian American 28 Chinese American 28-32 Filipino