Urban and Rural Public Spaces: Development Issues and Qualitative Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HARMONOGRAM ODBIORU ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH – GMINAKROBIA Obowiązuje Od 01.01.2015 R

HARMONOGRAM ODBIORU ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH – GMINAKROBIA obowiązuje od 01.01.2015 r. do31.12.2016 r. 1. Dane firmy odbierającej odpady komunalne: PHU TRANS-KOM Barbara Rajewska, Bogusławki 8B, 63-800 Gostyń tel. 65 572 37 75, 604 424 590; www.trans-kom.com.pl; e-mail: [email protected] 2. Pojemnik należy wystawić przed posesją, w miejscu łatwo dostępnym,do godziny 6:00 rano. 3. W przypadku, gdy w ustalony dzień tygodnia dla odbioru odpadów zmieszanychprzypada dzień ustawowo wolny od pracy, odbiór odpadów odbędzie się w następnym dniu niebędącym dniem ustawowo wolnym od pracy. 4. W przypadku, gdy w ustalony dzień tygodnia dla odbioru odpadów segregowanych przypada dzień ustawowo wolny od pracy, odbiór odpadów odbędzie się w najbliższą sobotę. GMINA KROBIA Pijanowice, Bukownica, Stara Krobia, Żychlewo, Wymysłowo, Chumiętki NIERUCHOMOŚCI ZAMIESZKAŁE odpady komunalne zmieszane każda środa miesiąca odpady komunalne papier, tworzywa sztuczne i metale, szkło bezbarwne, szkło I środa miesiąca segregowane kolorowe dodatkowa zbiórka tworzyw sztucznych i metali od kwietnia do września III środa miesiąca 29 kwiecień, 30wrzesień 2015 zbiórka objazdowa (odpady wielkogabarytowe oraz zużyty sprzęt elektryczny i elektroniczny) 9 kwiecień, 1 październik 2016 NIERUCHOMOŚCI NIEZAMIESZKAŁE odbiór 1 / miesiąc IIśroda miesiąca odpady komunalne zmieszane w przypadku częstszego odbioru - zgodnie z indywidualnym Firmy zgłoszeniem właściciela nieruchomości i odpady komunalne segregowane instytucje (papier, tworzywa sztuczne i metale, szkło bezbarwne, odbiór 1 -

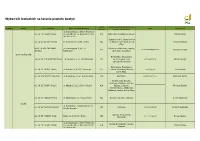

Wykaz Kół Łowieckich Na Terenie Powiatu Gostyń

Wykaz kół łowieckich na terenie powiatu Gostyń numer miejscowości przynależne do powiat gmina koło łowieckie adres korespondencyjny mail Prezes Koła obwodu obwodu łowieckiego ul. Drzęczewska 1, 63-820 Piaski; do K.Ł. Nr 19 "JELEŃ" Piaski korespondencji: ul. Rycerska 22, 63- 418 Dąbrówka, Grodnica, Koszkowo Marian Piasny 860 Pogorzela Siedmiorogów I, Siedmiorogów K.Ł. Nr 20 "Łowca" Krobia Pl. Kościuszki 3, 63-840 Krobia 422 II, Karolew, Lisie Góry, Borek Jerzy Giernalczyk Wlkp. W.K.Ł. Nr 418 "WIDAWA" ul. Inwestycyjna 3, 55-040 Koszkowo, Wycisłowo, Jawory, 417 [email protected] Jan Bartoszewicz Wrocław Kobierzyce Skokówko, Strumiany Borek Wielkopolski Borek Wlkp., Trzecianów, W.K.Ł. Nr 316 "ŁOŚ" Warszawa ul. Gościnna 2, 03-295 Warszawa 423 Siedmiorogów I i II, [email protected] Marek Papuga Celestynów, Głoginin Zimnowoda, Bolesławów, K.Ł. Nr 21 "RUDEL" Rusko ul. Szkolna 10, 63-233 Jaraczewo 414 Leonów, Bruczków, Skoków, [email protected] Józef Bandyk Borek Wlkp. K.Ł. Nr 425 "KSZYK" Wrocław ul. Różyckiego 1c, 51-608 Wrocław 328 Studzianna [email protected] Waldemar Dubas Gostyń, Gola, Kosowo, Siemowo, Stankowo, Osowo, K.Ł. Nr 21 "DROP" Gostyń ul. Mieszka I 3/13, 63-800 Gostyń 419 Stężyca, Daleszyn, Mirosław Ziemski Szczodrochowo, Dalabuszki, Daleszyn, Dusina, Gostyń Stary K.Ł. Nr 18 "DIANA" Poniec ul. Mickiewicza 24, 64-125 Poniec 421 Gostyń, Krajewice, Ziółkowo Stefan Napierała Gostyń ul. Powstańca Lewandowskiego 23, K.Ł. Nr 28 "SZARAK" Krzywiń 339 Stankowo [email protected] Wojciech Budziński 64-010 Krzywiń Kunowo, Tworzymirki, K.Ł. Nr 75 "KNIEJA" Dolsk Miranowo 1, 63-140 Dolsk 329 [email protected] Roman Weber Dalabuszki ul. -

GMINA KROBIA 2019 Rok

HARMONOGRAM ODBIORU ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH - GMINA KROBIA 2019 rok Dane firmy odbierającej odpady komunalne: „ZGO-NOVA” Sp. z o.o., ul. T. Kościuszki 21A, 63-200 Jarocin, tel. 533 320 869 / e-mail: [email protected] / www.zgo-nova.pl 1. Odpady należy wystawić przed posesję w miejscu łatwo dostępnym, do godziny 6:00 rano (również zbiórki objazdowe). 2. Worki z odpadami segregowanymi powinny być pełne i zawiązane. Do worków należy wrzucać puste, zgniecione plastikowe butelki i opakowania, złożone kartony, niepotłuczone szkło! Krobia 1 NIERUCHOMOŚCI ZAMIESZKAŁE ODPADY KOMUNALNE SEGREGOWANE ODPADY KOMUNALNE papier, tworzywa sztuczne BIOODPADY dodatkowa zbiórka tworzyw ZMIESZANE i metale, szkło bezbarwne, sztucznych i metali szkło kolorowe STYCZEŃ: 02.01; 16.01; 30.01 STYCZEŃ: 9.01; 23.01 STYCZEŃ: 9.01 LUTY: 13.02; 27.02 LUTY: 6.02; 20.02 LUTY: 13.02 MARZEC: 13.03; 27.03 MARZEC: 6.03; 20.03 MARZEC: 13.03 KWIECIEŃ: 10.04; 24.04 KWIECIEŃ: 3.04; 17.04 KWIECIEŃ: 10.04 KWIECIEŃ: 24.04 MAJ: 08.05; 22.05 MAJ: 2.05; 15.05; 29.05 MAJ: 8.05 MAJ: 22.05 CZERWIEC: 05.06; 19.06 CZERWIEC: 12.06; 26.06 CZERWIEC: 12.06 CZERWIEC: 26.06 LIPIEC: 03.07; 17.07; 31.07 LIPIEC: 10.07; 24.07 LIPIEC: 10.07 LIPIEC: 24.07 SIERPIEŃ: 14.08; 28.08 SIERPIEŃ: 7.08; 21.08 SIERPIEŃ: 14.08 SIERPIEŃ: 28.08 WRZESIEŃ: 11.09; 25.09 WRZESIEŃ: 4.09; 18.09 WRZESIEŃ: 11.09 WRZESIEŃ: 25.09 PAŹDZIERNIK: 9.10; 23.10 PAŹDZIERNIK: 2.10; 16.10; 30.10 PAŹDZIERNIK: 9.10 LISTOPAD: 6.11; 20.11 LISTOPAD: 13.11; 27.11 LISTOPAD: 13.11 GRUDZIEŃ: 4.12; 18.12 GRUDZIEŃ: 11.12; 27.12 GRUDZIEŃ: 11.12 Zbiórka -

Village German

Village Polish, Lithuanian, Village German (Village today), Powiat today, Woiwodschaft today, Country North East Russian County German Province German Abelischken/Ilmenhorst (Belkino), Pravdinsk, Kaliningrad, German Empire (Russia) 542529 213708 Белкино Gerdauen Ostpreussen Ablenken (Oplankys), , Taurage, German Empire (Lithuania) 551020 220842 Oplankys Tilsit Ostpreussen Abschermeningken/Almental (Obszarniki), Goldap, Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German Empire (Poland) 542004 220741 Obszarniki Darkehmen Ostpreussen Abschwangen (Tishino), Bagrationovsk, Kaliningrad, German Empire (Russia) 543000 204520 Тишино Preussisch Eylau Ostpreussen Absteinen (Opstainys), Pagegiai, Taurage, German Empire (Lithuania) 550448 220748 Opstainys Tilsit Ostpreussen Absteinen (W of Chernyshevskoye), Nesterov, Kaliningrad, German Empire (Russia) 543800 224200 Stallupoenen Ostpreussen Achodden/Neuvoelklingen (Ochodno), Szczytno, Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German Empire (Poland) 533653 210255 Ochódno Ortelsburg Ostpreussen Achthuben (Pieszkowo), Bartoszyce , Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German Empire (Poland) 541237 203008 Pieszkowo Mohrungen Ostpreussen Adamsdorf (Adamowo), Brodnica, Kujawsko‐Pomorskie, German Empire (Poland) 532554 190921 Adamowo Strasburg I. Westpr. Westpreussen Adamsdorf (Maly Rudnik), Grudziadz, Kujawsko‐Pomorskie, German Empire (Poland) 532440 184251 Mały Rudnik Graudenz Westpreussen Adamsdorf (Sulimierz), Mysliborz, Zachodniopomorskie, German Empire (Poland) 525754 150057 Sulimierz Soldin Brandenburg Adamsgut (Jadaminy), Olsztyn, Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German -

Marszałek Województwa Marek Woźniak

Uchwała Nr 4138/2017 Zarządu Województwa Wielkopolskiego z dnia 23 sierpnia 2017 r. zmieniająca uchwałę Nr 342/2007 Zarządu Województwa Wielkopolskiego z dnia 10 maja 2007 r. w sprawie: nadania numerów dla dróg gminnych w województwie wielkopolskim. Na podstawie art. 10 ust. 7 pkt 2 Ustawy z dnia 21 marca 1985 r. o drogach publicznych (t. j. Dz. U. z 2016 r., poz. 1440 ze zm.) Zarząd Województwa Wielkopolskiego uchwala, co następuje: § 1 1. W uchwale Nr 342/2007 Zarządu Województwa Wielkopolskiego z dnia 10 maja 2007 r. w sprawie: nadania numerów dla dróg gminnych w województwie wielkopolskim wprowadza się zmiany następujących załączników do uchwały: 1. załącznik nr 22 Gmina Czempiń 2. załącznik nr 56 Gmina Kawęczyn 3. załącznik nr 60 Gmina Kiszkowo 4. załącznik nr 79 Miasto Kórnik 5. załącznik nr 83 Miasto Krobia 6. załącznik nr 98 Gmina Lubasz 7. załącznik nr 131 Miasto i Gmina Osieczna 8. załącznik nr 164 Gmina i Miasto Rychwał 9. załącznik nr 195 Miasto Trzcianka 10. załącznik nr 205 Miasto i Gmina Wieleń 11. załącznik nr 211 Gmina Władysławów 12. załącznik nr 225 Gmina Żelazków 2. Załączniki, o których mowa w ust. 1 pkt 1-12, otrzymują brzmienie, jak w załącznikach do niniejszej uchwały. § 2 Wykonanie uchwały powierza się Dyrektorowi Departamentu Infrastruktury Urzędu Marszałkowskiego Województwa Wielkopolskiego. § 3 Uchwała wchodzi w życie z dniem podjęcia. Marszałek Województwa Marek Woźniak Uzasadnienie do Uchwały Nr 4138/2017 Zarządu Województwa Wielkopolskiego z dnia 23 sierpnia 2017 r. Uchwała Nr 342/2007 Zarządu Województwa Wielkopolskiego z dnia 10 maja 2007 r. w sprawie: nadania numerów dla dróg gminnych w województwie wielkopolskim została podjęta na podstawie Ustawy z dnia 21 marca 1985 r. -

Woj. Wielkopolskie - Pow

woj. wielkopolskie - pow. chodzieski BUDZYŃ – m. i gm. Budzyń - kościół par. pw. św. Barbary, 1849, nr rej.: 542/Wlkp/A z 30.09.1971 - cmentarz ewangelicki, nieczynny, ul. Wągrowiecka, 2 poł. XIX, nr rej.: 545/Wlkp/A z 29.07.1988 - dom, ul. Rynkowa 22, 1 poł. XIX, nr rej.: A-1262 z 30.09.1971 (nie istnieje) - dom, ul. Rynkowa 30 (d.28), poł. XIX, nr rej.: 543/Wlkp/A z 30.09.1971 - dom, ul. Rynkowa 45, poł. XIX, nr rej.: 539/Wlkp/A z 30.09.1971 - wiatrak paltrak, XIX/XX, nr rej.: 544/Wlkp/A z 22.09.1977 Bukowiec - kościół ewangelicki, ob. rzym.kat. fil. pw. NMP Różańcowej, 1863, nr rej.: 546/Wlkp/A z 16.11.1990 Dziewoklucz - park dworski, 2 poł. XIX, nr rej.: A-549 z 28.09.1987 Podstolice - kościół par. pw. św. Kazimierza, 1932-35, nr rej.: 673/Wlkp/A z 14.05.2008 - cmentarz kościelny, nr rej.: j.w. Sokołowo Budzyńskie - kościół ewangelicki, ob. rzym.kat. fil. pw. Niepokalanego Serca NMP, 1846, nr rej.: 547/Wlkp/A z 16.11.1990 - chałupa, drewn., nr 13, 2 poł. XVIII, nr rej.: wpisana do inwentarza muzealnego, przeniesiona → Muzeum Pierwszych Piastów na Lednicy → Dziekanowice Wyszynki - cmentarz ewangelicki, 2 poł. XIX, nr rej.: 538/Wlkp/A z 29.07.1988 Wyszyny - kościół par. pw. MB Pocieszenia, k. XVII, 1825-35, nr rej.: 548/Wlkp/A z 30.09.1971 CHODZIEŻ – gm. Milcz - cmentarz katolicki, nr rej.: A-711 z 11.10.1990 Nietuszkowo - kapliczka cmentarna, 1879, nr rej.: A-715 z 5.11.1990 - zespół pałacowy, 2 poł. -

GMINA KROBIA 2019 Rok

HARMONOGRAM ODBIORU ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH - GMINA KROBIA 2019 rok Dane firmy odbierającej odpady komunalne: „ZGO-NOVA” Sp. z o.o., ul. T. Kościuszki 21A, 63-200 Jarocin, tel. 533 320 869 / e-mail: [email protected] / www.zgo-nova.pl 1. Odpady należy wystawić przed posesję w miejscu łatwo dostępnym, do godziny 6:00 rano (również zbiórki objazdowe). 2. Worki z odpadami segregowanymi powinny być pełne i zawiązane. Do worków należy wrzucać puste, zgniecione plastikowe butelki i opakowania, złożone kartony, niepotłuczone szkło! Krobia 1 NIERUCHOMOŚCI ZAMIESZKAŁE ODPADY KOMUNALNE SEGREGOWANE ODPADY KOMUNALNE papier, tworzywa sztuczne BIOODPADY dodatkowa zbiórka tworzyw ZMIESZANE i metale, szkło bezbarwne, sztucznych i metali szkło kolorowe STYCZEŃ: 02.01; 16.01; 30.01 STYCZEŃ: 9.01; 23.01 STYCZEŃ: 9.01 LUTY: 13.02; 27.02 LUTY: 6.02; 20.02 LUTY: 13.02 MARZEC: 13.03; 27.03 MARZEC: 6.03; 20.03 MARZEC: 13.03 KWIECIEŃ: 10.04; 24.04 KWIECIEŃ: 3.04; 17.04 KWIECIEŃ: 10.04 KWIECIEŃ: 24.04 MAJ: 08.05; 22.05 MAJ: 2.05; 15.05; 29.05 MAJ: 8.05 MAJ: 22.05 CZERWIEC: 05.06; 19.06 CZERWIEC: 12.06; 26.06 CZERWIEC: 12.06 CZERWIEC: 26.06 LIPIEC: 03.07; 17.07; 31.07 LIPIEC: 10.07; 24.07 LIPIEC: 10.07 LIPIEC: 24.07 SIERPIEŃ: 14.08; 28.08 SIERPIEŃ: 7.08; 21.08 SIERPIEŃ: 14.08 SIERPIEŃ: 28.08 WRZESIEŃ: 11.09; 25.09 WRZESIEŃ: 4.09; 18.09 WRZESIEŃ: 11.09 WRZESIEŃ: 25.09 PAŹDZIERNIK: 9.10; 23.10 PAŹDZIERNIK: 2.10; 16.10; 30.10 PAŹDZIERNIK: 9.10 LISTOPAD: 6.11; 20.11 LISTOPAD: 13.11; 27.11 LISTOPAD: 13.11 GRUDZIEŃ: 4.12; 18.12 GRUDZIEŃ: 11.12; 27.12 GRUDZIEŃ: 11.12 Zbiórka -

Powiat Gmina Miejscowośd Liczba Ludności Węzeł WSS Kategoria

Powiat Gmina Miejscowośd Liczba ludności Węzeł WSS Kategoria Inwestycje TP BSC_infrastrukturalne BSC_podstawowe BSC_NGA chodzieski Budzyo Brzekiniec 242 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Budzyo 4 280 1 2b 1 S S B chodzieski Budzyo Bukowiec 359 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Dziewoklucz 450 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Budzyo Grabówka 170 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Kąkolewice 159 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Niewiemko 42 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Budzyo Nowa Wieś Wyszyoska 102 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Budzyo Nowe Brzeźno 235 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Ostrówki 257 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Podstolice 304 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Budzyo Popielno 32 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Budzyo Prosna 406 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Sokołowo Budzyoskie 503 1 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Budzyo Wyszynki 127 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Budzyo Wyszyny 783 1 2b 0 S S B chodzieski Chodzież Chodzież 19 604 1 7a 1 C C S chodzieski Chodzież Cisze 20 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Chodzież Ciszewo 5 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Chodzież Drzązgowo 4 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Chodzież Jacewko 2 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Chodzież Jacewo 0 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Chodzież Kamionka 71 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Chodzież Kierzkowice 42 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Chodzież Konstantynowo 116 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Chodzież Krystynka 47 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Chodzież Milcz 495 1 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Chodzież Mirowo 57 0 1a 0 B B B chodzieski Chodzież Nietuszkowo 354 0 2b 0 S S B chodzieski Chodzież Oleśnica 349 0 2b 0 S S B chodzieski Chodzież Pietronki 158 0 1b 0 B S B chodzieski Chodzież Podanin -

Realizacjalsr.Pdf

Gościnna Realizacja Lokalnej Strategii Rozwoju Lokalnej Grupy Działania Gościnna Wielkopolska Wielkopolskaw latach 2009-2015 Gościnna Wielkopolska Szanowni Państwo, Stowarzyszenie „Lokalna Grupa Działania Gościn- Realizacja Lokalnej Strategii Rozwoju na Wielkopolska” z siedzibą w Pępowie to trójsek- Lokalnej Grupy Działania Gościnna Wielkopolska torowe partnerstwo obejmujące obszar jedenastu w latach 2009-2015 gmin położonych w południowej Wielkopolsce, w których mieszka blisko 100 tysięcy mieszkańców. Autorzy tekstów: Hubert Gonera Grzegorz Niklas Partnerstwo budowaliśmy kilka lat, przygotowując Konsultacje merytoryczne: Urszula Pużanowska stabilny fundament do opracowania i przyjęcia do Korekta: Kasia Robaczewska realizacji Lokalnej Strategii Rozwoju. Solidna pra- Zdjęcia: Piotr Benenowski ca przyniosła efekty. Wojciech Górny Agencja Reklamowa DNA Nasza strategia została wysoko oceniona i zdobyła Archiwum LGD Gościnna Wielkopolska Archiwa beneficjentów pierwsze miejsce w Wielkopolsce w konkursie ogło- szonym przez Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Opracowanie, projekt graficzny i skład: landbrand Wielkopolskiego. Wydawca: Stowarzyszenie „Lokalna Grupa Działania Gościnna Wielkopolska” Z satysfakcją i zapałem przystąpiliśmy do realizacji zapisów strategii i wydatkowania blisko piętnasto- milionowego budżetu środków pochodzących z Osi www.goscinnawielkopolska.pl 4 Leader Programu Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich na lata 2007-2013. Pępowo 2015 Pracowaliśmy przez te lata wspólnie, dążąc do realizacji projektów o znaczącym wpływie na rozwój funkcji -

Aktualizacja 2014 R. CHUMIĘTKI CMENTARZ EWANGELICKI, 2 Poł

GMINNA EWIDENCJA ZABYTKÓW GMINA KROBIA – aktualizacja 2014 r. CHUMIĘTKI CMENTARZ EWANGELICKI, 2 poł. XIX w. ZESPÓŁ DWORSKI: a. park, k. XIX w., b. ogrodzenie, mur., k. XIX w. DOM NR 21, mur., pocz. XX w. CHWAŁKOWO ZESPÓŁ KOŚCIOŁA PAR. P.W. ŚWIĘTEJ TRÓJCY a. kościół, nr 42, mur., 1854 r., cz. zniszcz. 1939-1945, odbud. i rozbud. 1947 r., b. grobowiec rodziny Bojanowskich, ob. kaplica cmentarna, mur., 2 poł. XIX w., c. cmentarz przykościelny, poł. XIX w., d. ogrodzenie z bramą, mur.-żel., l. 30 XX w. SZKOŁA, ob. dom nr 48, mur., 1 ćw. XX w. SZKOŁA, ob. biblioteka nr 43, mur., k. XIX w. w. ZESPÓŁ PAŁACOWO – FOLWARCZNY: a. pałac nr 73, mur., 1910 r., b. park, ok. poł. XIX w., XX w., c. rządcówka nr 45, mur., 4 ćw. XIX w., d. park przy rządcówce, 2 poł. XIX w., e. spichlerz, mur., ok. poł. XIX w., f. ogrodzenie z bramami, mur., ok. 1890 r., g. lodownia, mur., k. XIX w., h. obora, mur., 1872 r., i. obora, mur., k. XIX w., j. obora, mur., 1902 r., k. stodoła, mur., 1890 r., l. stodoła, mur., 2 poł. XIX w., ł. warsztat, mur., k. XIX w., m. mleczarnia, mur., 4 ćw. XIX w., n. dom nr 76, mur., k. XIX w., 1 o. dom nr 82, mur., 1914 r., p. dom nr 75, mur., k. XIX w., r. dom nr 35, mur., 1905 r., s. ośmiorak nr 46, mur., 2 poł. XIX w., t. dom nr 77, mur., k. XIX w. DOM NR 22, mur., 1 ćw. XX w. -

Biskupizna ZIEMIA – TRADYCJA – TOŻSAMOŚĆ

Biskupizna ZIEMIA – TRADYCJA – TOŻSAMOŚĆ Redakcja naukowa Anna Weronika Brzezińska Marta Machowska Krobia 2016 biskupizna_książka_po_korekcie_druk.indb 1 2016-12-12 12:43:30 Książka jest efektem współpracy Gminnego Centrum Kultury i Rekreacji w Krobi oraz Instytutu Etnologii i Antropologii Kulturowej Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu Recenzenci: dr Anna Drożdż, Wydział Etnologii i Nauk o Edukacji, Uniwersytet Śląski w Cieszynie dr Arkadiusz Jełowiecki, Narodowe Muzeum Rolnictwa i Przemysłu Rolno-Spożywczego w Szreniawie Korekta językowa: Wioletta Sytek Tłumaczenia na j. angielski: Kinga Haligowska Tłumaczenia na j. niemiecki: Biuro tłumaczeń „Alingua” Projekt graficzny, skład i łamanie: Katarzyna Bordziuk Na okładce wykorzystano fotografię panoramy Wymysłowa autorstwa Karoliny Dziubatej Europejski Fundusz Rolny na rzecz Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich: Europa inwestująca w obszary wiejskie Instytucja Zarządzająca PROW 2014-2020 Minister Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi Publikacja powstała w ramach operacji „Na Biskupiźnie działamy razem”. Materiał współfinansowany ze środków Unii Europejskiej w ramach Krajowej Sieci Obszarów Wiejskich Programu Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich na lata 2014 – 2020 Wydawca: Gminne Centrum Kultury i Rekreacji im. Jana z Domachowa Bzdęgi w Krobi ul. Powstańców Wlkp. 27, 63-840 Krobia www.kultura.krobia.pl, www.biskupizna.pl Egzemplarz bezpłatny Wersja elektroniczna dostępna: http://cyfrowearchiwum.amu.edu.pl/ Druk: Drukarnia Internetowa – mPrint Mikołaj Andrzejewski Mproject ul. Ogrodowa 5, 63-840 Krobia ISBN: 978-83-940159-2-3 -

840 Krobia 8

OBWIESZCZENIE Burmistrza Krobi z dnia 4 września 2019 roku Na podstawie art. 16 § 1 ustawy z dnia 5 stycznia 2011 r. – Kodeks wyborczy (Dz. U. z 2019 r. poz. 684 i 1504) Burmistrz Krobi podaje do wiadomości wyborców informację o numerach oraz granicach obwodów głosowania, wyznaczonych siedzibach obwodowych komisji wyborczych oraz możliwości głosowania korespondencyjnego i przez pełnomocnika w wyborach do Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej i do Senatu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej zarządzonych na dzień 13 października 2019 r.: Nr obwodu Granice obwodu głosowania Siedziba obwodowej komisji wyborczej głosowania Krobia: Adama Asnyka, Aleksandra Fredry, Bolesława Prusa, Jutrosińska, Miejsko-Górecka, Nowa, Odrodzenia, Rynek, Stefana Żeromskiego, Św. Ducha, Tadeusza Różewicza, Wiosenna, Biskupiańska, Pałac Ślubów, Pl. Tadeusza Kościuszki 3, 63-840 1 Domachowska, Kasztelańska, Latowa, Ogród Ludowy, Krobia Polna, Południowa, Poznańska, prof. Józefa Zwierzyckiego, Szkolna, Św. Idziego, pl. Tadeusza Kościuszki, Kobylińska, Targowa, Wały, Zajazdowa, Brzoskwiniowa Krobia: 1 Maja, Dworcowa, Franciszka Rejka, Jana Piko, Klonowa, Lipowa, Powstańców Wielkopolskich, Adama Mickiewicza, Harcerska, Jana III Sobieskiego, Kino Szarotka, ul. Powstańców Wielkopolskich 27, Janusza Korczaka, Juliusza Słowackiego, Łąkowa, 63-840 Krobia Parkowa, Poniecka, Ogrodowa, Zachodnia, Cicha, 2 Cypriana Kamila Norwida, Grunwaldzka, Henryka Lokal dostosowany do potrzeb wyborców niepełnosprawnych Sienkiewicza, Juliana Tuwima, Kwiatowa, Marii Konopnickiej, Mikołaja Kopernika, Pogodna,